Maybe there exists somewhere a satisfying historical account of ethyl alcohol in relation to human beings, but if so I haven’t seen it, and I’ve read a few attempts. My interest in the subject, I’d better establish to begin with, does not stem from being what one of my daughters as a child, having read the word but not heard it, used to call a drun-kard. Rather it derives from a long-standing friendship with the substance, appreciative and grateful for the most part but also pretty wary, so that my appreciation has managed to survive several decades during which I’ve watched a good number of harder-drinking contemporaries, true drunkards’ some of them, though others were stout fellows, go downs the drain to psychic wreck, cirrhosis, or abstinence.

What I’ve wondered for a long time now is whether mankind’s affinity for this stuff isn’t fundamentally inborn. Much of botanic nature is an alcohol factory at times, and many lesser creatures take pleasure in this fact, as anyone knows who has watched wasps and beetles and mockingbirds gloriously swacked on spoiled fruit fallen from trees, or cedar waxwings merry after a feast of fermented pyracantha berries, or cows and pigs clumsily full of well-being from a bait of extra-stout silage. Thus it isn’t hard to conjure up the image of some shambling bristly forebear of H. sapiens who, with the beginnings of thrift and foresight flickering about in whatever he had for a mind, gorged himself at some point on a felicitous bonanza of fruit or wild grain or honey, stashed what he couldn’t eat in a hollow tree, and came back a few days later to find that moisture and other forces had wrought a wonder. The cache was now a mush of rudimentary beer or wine that made him feel magnificent when he scoffed it up, at least for a brief while, after which he may have felt worse than he ever had before.

Perhaps in losing its cares and worries for that brief while, his primitive thinking apparatus achieved a liberation, grew creative in the manner sometimes attributed to drunkenness by far later generations of hominids, and dreamed up a way of crunching his fellows’ skulls with a sharp rock and thus getting possession of whatever they had accumulated in the way of fruit or grain or honey or females. And perhaps in turn this gave him dominance and an edge in the Darwinian contest, which he passed down to his descendants along with a taste for hooch. (I know there’s a touch of discredited Lamarckism here, but let it stand.) At any rate it could have happened in more or less that way, being no more improbable than such genetic arrangements as the symbiosis between yucca moths and yucca.

Nor is there much doubt in my mind that this same treasured and troublesome intermediate product of sugar on its way to becoming vinegar has been a factor, at times a potent one, in human history of the sort we read in books. We all know for a fact that there’s usually a good bit of difference—not necessarily in flavor but in degree—between an individual’s normal sober behavior and what he does when drunk, in which condition the dark irrational id comes closer to the surface of things and sometimes takes command. We know too that a certain proportion of people, when social restraints are lacking or shucked off and alcohol is available, will stay drunk pretty much of the time.

With these givens, what is certain is that during eras of history when democracy was unheard of and the brute power of rulers was subject to few restraints save the brute power of other rulers or would-be rulers, full many a brutal drunk must have made full many a decision as to the waging of war, the execution of underlings in perhaps large numbers when they displeased him, and the elevation to high rank of idiots or psychopaths who did things he liked at a certain fuddled moment. I find it very hard otherwise to account for much that we know has been done during the past three or four thousand years, even if certain forms of probably nonalcoholic intoxication must have come into it also, as with the religiously inspired massacres conducted by ancient Assyrians and Hebrews and such, and the berserker rage of ravaging Vikings—though we’re aware, of course, that the Vikings were heroic drinkers whenever they got a good chance.

That tendency toward binges has been passed down, apparently, to large numbers of their relatively mild descendants the Scandinavians, and is shared for that matter by most North European peoples, including us Americans’ principal Old World cousins and forebears, the British and the Irish. Whence it follows that we ourselves should show the tendency too, as the Lord knows we do and have ever since we first came here. Bills of lading from vessels serving these colonies in the old days, as well as diaries and recipe books and letters and the like, make it evident that a notable fraction of our early New World ancestors, at least outside the more God-fearing parts of New England, found joy in having not only plenty to drink but rather often more than plenty.

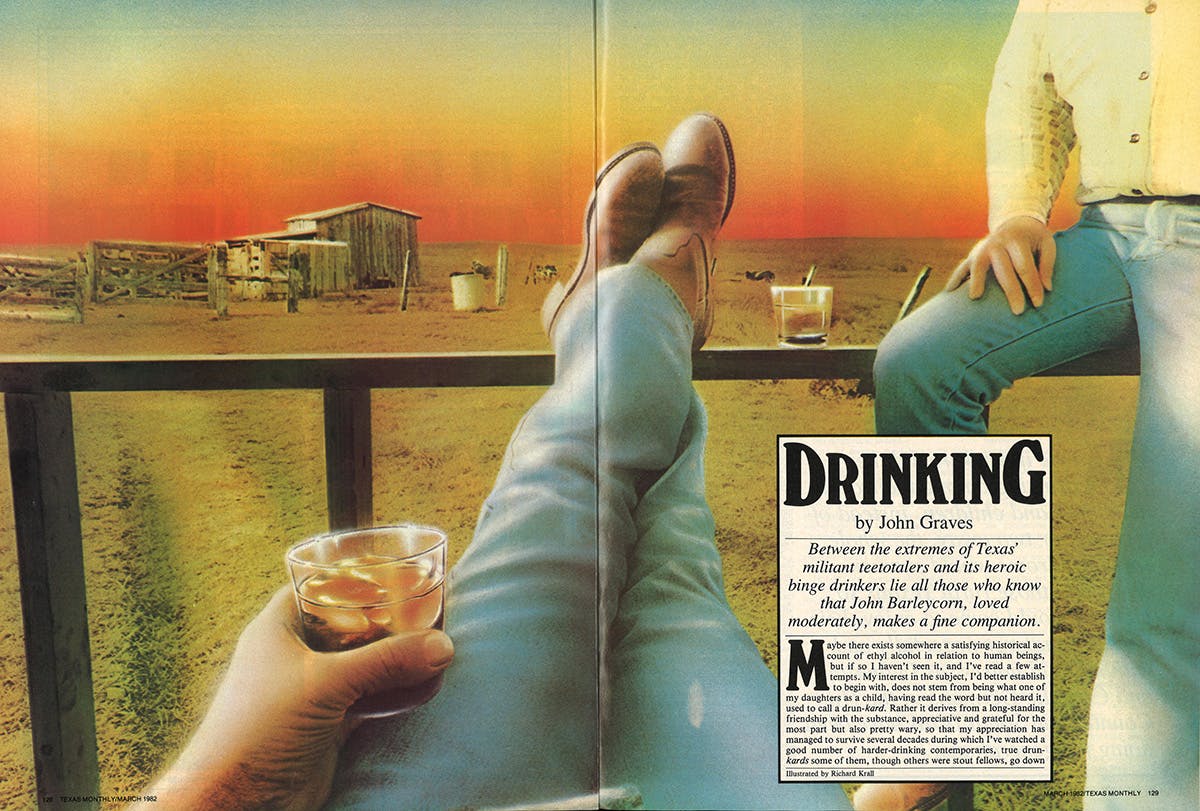

Nor did conditions along the frontier, as Americans heroic or otherwise edged westward, do anything to diminish this ethnic affinity for excess when excess was available. Raw hard liquor seems to have been just about as essential a fuel for the transcontinental migration as was a sense of manifest destiny. And if at this range of years it is not hard to view as quaint the sometimes homicidal antics of men who capped off months of tough work and deprivation with mighty sprees at a fur traders’ rendezvous or a Kansas railhead cattle town, it isn’t very hard either, if you live in a place like Texas, to find somewhat less quaint evidence of the legacy those men left us. All you have to do is pay a visit on Saturday night to the honky-tonk fringe of one of our spraddling cities, where sprees and homicides flourish.

There are other ways to drink besides heroically, of course, as traditionally exemplified in those nationalities who for the most part sip their wine with moderation and quiet enjoyment along the sunlit shores of the Mediterranean. Though the main difference between their habits and ours is undoubtedly cultural—racial, I’ve heard some Mediterranean chauvinists claim—the question of what each culture chooses to drink may come into it too. This whole matter of the distinct effects produced by various liquids is fascinating, at least to drinkers, but it is also very hazy. An authoritative treatise I once read lumped all nonalcoholic components together as “congeners” and implied, as I remember, that they served only to give flavor and mystique to whatever it was you were drinking and not to exert any real influence on your reactions. The alcohol was all that actually counted.

From experience I know this to be untrue in the case of certain druggishly treacherous fluids like absinthe and mescal. I suspect it’s also untrue with regard to some of the beliefs cherished by bibbers in their voluminous lore on the subject: beer promotes good fellowship and music, champagne high merriment and romance, honest table wine a sense of well-being, skid row Sweet Lucy stumbling soddenness, excessive hard liquor combativeness and uproar, and so on infinitely.

There does appear to be scant variation in what is done to you by standard distilled spirits of the sort commonly used in this country—whiskey, gin, vodka, rum—except for the size of the hangovers they or their mixers can give. But what is one to say about brandy, for instance, which, as all know who have at one time or another let themselves love it too well, will wake you at three or four in the morning with your heart trying to imitate a jackhammer and all the fears and pessimisms and inadequacies you’ve ever experienced dancing a hornpipe on your taut-stretched consciousness?

No difference, indeed.

And of course, mind being the force that it is, drinkers’ lore tends to come true even when its underpinnings are shaky. If you believe steadfastly that sloe gin will help you whip a highway-cabaretful of pipeline workers, then sloe gin will probably make that sort of drunk out of you if not always that sort of fighter, just as Veuve Clicquot or Taittinger or Mumm’s, coursing the arterioles of the faithful, will generate gaiety and wit and seductive patrician charm.

Nondrinkers’ notions about alcohol are a bit more problematic. My Baptist maternal grandmother believed, without having tried either one, that beer was stronger and more pernicious than whiskey. This was because during the local-option elections of the thirties following Repeal, those stalwarts who were trying to alleviate the dryness of their particular parts of rural or small-town Texas knew that distilled spirits, given their associations with pre-Volstead saloons and all that, were a foredoomed cause. Thus they concentrated their efforts, fruitless to this day in many sections, on trying to legalize beer and wine sales.

Fundamentalist preachers, in consequence, the kind my grandmother listened to in church and on the radio, attacked beer hardest of all—there not being many potential wine customers among their parishioners and wine, for that matter, being the source of some pious confusion since it was mentioned in Scripture and often with approval. An instance of this was harsh Saint Paul’s famous advice, the justificatory motto of many a secret Bible Belt toper, to use a little wine for the stomach’s sake—which, since “a little” was a negotiable quantity and “wine” could be construed as a metaphoric term for all drink, gave quite a bit of latitude if latitude was what you needed.

In her last days that same grandmother of mine, in fact, used to receive from my father each evening a small tumbler of straight bonded bourbon laced with grenadine syrup, which he tactfully described as wine and she gladly accepted as such. She was bedridden and in some pain and it helped, just as I expect old Paul’s sanction helped her to enjoy it.

I live most of the time in a county where if you’re sitting on a towndwelling friend’s lawn in the evening and a car drives up to the house and stops, you ease your beer can down by the leg of the chair until you can see who it is, even though carry-out beer and wine are now legal in the town’s precinct. Being an outsider, I don’t do this for my own sake but for that of my host, who has to live and function here in a more intimate and social sense than I, and the mild hypocrisy involved has never bothered me much. It is in truth a genuine Texas folkway, a part of the ethos of those wide reaches of the state where the harder-shelled forms of Protestantism prevail, and any Texan of my age and background and inclinations has been familiar with it all his life.

Neither am I disturbed by the fact that a number of drinking locals regularly vote dry when a wet-dry option comes up at election, as it still sometimes does despite the continuing strong presence of the nuclear plant construction workers who first voted the place wet a few years ago, or anyhow not entirely dry, and are keeping it that way. Some of these crosswise local voters are of course hung up on the schizoid dilemma that troubles puritan drinkers everywhere, for whom Saint Paul’s sanction doesn’t always suffice. But others are using good logic. Given the usual nature of Texas spree drinking and the sort of honky-tonks and street scenes it can engender, they prefer if possible to keep the centers of attraction, to which the denizens of dry places will flock from many miles around with uproarious escape from strictures as a goal, a county or two away from where they’re raising kids and trying to lead quiet lives.

Maybe if the entire state map went wet and drinkers did their drinking among their own neighbors and children, the whole spree syndrome would simmer down and those rural Texans so inclined would come to enjoy their beer or what ever peacefully and without loud noises, as Lutheran and Catholic Germans in the Hill Country and South Texas have been doing for generations. Not that I’d bet on it. But as the ancient Choctaw adage has it, if a frog had wings he wouldn’t wear his butt out hopping, and no one claims to see prospects of such a blanket change any time soon, though some change is certainly taking place.

Meanwhile I suppose it behooves those of us who dwell here in a condition of less than hard-shelled grace to keep on appreciating such folkways. Even if we do wonder occasionally, in a chicken-and-egg sort of way, whether this stark set of reigning shalt-nots, which abides at least fractionally in most Texans’ inner selves, was put together in its various denominational forms by our Anglo-Scotch-Irish predecessors to help them control utter beastliness (a possibility, in view of what we know of early times’ habits) or just pounced down like a bird of prey on this particular ethnic group for reasons of its own.

Despite some staunchly hard-shelled antecedents on my mother’s side, I grew up in my father’s people’s church, the one that Virginia evangelicals still snidely call Whiskeypalian, and I tend to be rather thankful for this fact though undoubtedly not for all the right reasons. Besides the superlative ringing peak English of the Authorized Version and the Book of Common Prayer, this venerable institution offered its Texas communicants certain further rich gifts as well. I know that other people got much the same things from other fairly soft-shelled sects, or even on their own, but these benefits came to me with an Episcopalian flavor and that’s where my gratitude flows.

Among them were a spotty, dubious, but enduring belief in free will, and a blessed if only partial release from the Calvinistic conviction of sinfulness that rolled all around us like a fog in those days when even most Texas cities were essentially still small towns, both for better and for worse. Sin to Episcopalians was bad stuff and not to be taken lightly, but it was expiable too and hence didn’t represent your irreversible progress toward the everlasting fires below. Nor, except insofar as you might have inhaled some secondhand Calvinism from the ambient fog, did you have to go around looking for sin under each bush and in all dark corners, wondering if every pleasure that chance presented to your grasp was a booby trap designed and handcrafted by the forces of evil for your perdition.

In terms of that pleasure called drinking, this meant that when you reached an age deemed proper, you were relatively free to go ahead and experiment without feeling the hot foul breath of Auld Reekie on your tender neck. And also without, I guess, the keen pleasure in forbidden sweets that puritan tipplers must feel, though most of us had experienced that pleasure earlier, before we’d reached the age deemed proper.

Like all young drinkers of whatever religious hue, I and others like me often overdid the thing for a time, but we weren’t encouraged in this by our elders. My father and the men he most often chose as friends had a general firm belief in what they called “holding your liquor,’’ which they tried to instill in the young. It was the dead opposite of spree drinking and meant one of two things. Either you drank all you felt like drinking and through iron exertion of your will never showed it more than barely, mellowly, or else you learned by experience how much you could handle and when drinking stayed within that limit.

This reasonable, socially oriented standard of consumption, it seems to me looking back, may well have created a good many more alcoholics and other individual casualties than bust-loose spree drinking ever has, for spree drinking by its nature is usually sporadic and occasional. In some people holding one’s liquor fosters rather steady drinking, since they aren’t being unruly and no one objects. And when age or other factors decrease their tolerance for alcohol, as age or other factors most inexorably will, the hooch sneaks up behind them and either turns them into staid and proper zombies, or makes them old-fashioned drun-kards with all the trimmings, or eats at their livers and other components, or sometimes has more spectacular effects.

One gentleman of my father’s generation, famed for his wit and magnetism and his ability to knock back tot after tot of good Scotch and never slur a word, went out on his lawn one midnight and started firing a revolver up into a Lombardy poplar that he claimed was full of sneering Bulgarians, and might have fired it also at the police who came to stop him except that by then he was out of cartridges. Convinced later by loved ones that whiskey had been the cause, he agreed to clinical help and managed to get out from under the curse of drink. But sad to relate, as sometimes with reformees, along with his glow and those Bulgarians vanished all his charm and humor. He became in fact a quite dull fellow.

Nevertheless, having myself in large part survived thus far and being mildly inclined toward positive thinking, I believe I’d rather have been brought up to honor—and often to dodge—precepts that place blame on drunkenness and not on drinking than to have had to fight my way through thickets of guilt toward enjoyment of what is after all, if handled rightly, one of the more solid boons this grubby and turbulent species of ours has yet received. That it is often handled wrongly I know as well as anyone. I don’t find amusement in drunken slobs, and have watched for many years, sometimes from a lot closer than I wanted to be, the whole sorry spectacle of alcohol’s abuse—the shattering of talent and self-respect, the decay of families and other relationships, the collapse of health, the lifeblood spilled out on highways, and all of the miserable rest.

But I seem not to be able to rid myself of a quaint notion, maybe based on that spotty archaic faith I still have in free will, that these are things that people do with alcohol rather than things that alcohol does to people, for the stuff has been among us now for untold ages and we all know its negative potential, or damned well ought to know it. And often when conversation or somebody’s earnest writing or a TV show grows solemn about the Alcohol Problem, I find myself thinking of the beloved and bibulous cowboy artist Charles M. Russell, who in his pleasant book Trails Plowed Under began a tale with the words “Whiskey has been blamed for lots it didn’t do.”

So have beer and wine and gin and brandy and vodka and rum, and so, I doubt not in the least, have ouzo and pulque and koumiss and slivovitz and palm beer and sake and such, in those societies where one or another of these many-flavored delights is the fermented solace of choice. They didn’t do it, whatever it was. People did.

And all the while with the aid of these same liquids other people, millions on millions of them, have been relaxing when they need to relax, easing their disappointments and fears and angers and their bodies’ aches and fatigues, warming themselves when cold, cooling themselves when hot, rendering their tongues more eloquent, getting to know their fellows and on occasion to love them, singing and dancing and rosily glowing, sometimes thinking great thoughts even if in the aftermath, queerly, the greatness has most often washed away. And living, most of them, to a ripeness of years while causing very scant trouble—far less, I’d venture, than is caused by most brother’s keepers.

I’ve always believed in people’s not drinking if that’s what they want or need, and some most definitely do need not to drink at all, for their own sake and the world’s. Long residence in rural Texas has mellowed me now to the point that I don’t really much mind their not wanting the rest of us to drink either, as long as they can’t enforce it. And the fact that they can’t was proved for all time by Prohibition, which did more to promote hard and heavy spree drinking, if it needed promotion, than anything that’s happened in recent centuries, including wars.

My own requirements as to drink are modest these days: with the evening meal some decent wine, that calmest and gentlest and most civilized of potions, and now and then when bushed or tense or just in convivial company, a few relaxing, tongue-loosening belts of harder fuel. Not that I was ever much of a hero in these terms save during some periods of careless youth. Like most people of my vintage who’ve escaped being sucked down that particular drain, I seem to have felt out a long while back what alcohol can and can’t do for me and wherein it might be a threat, and most of the time I live unfretfully within the idiosyncratic pattern this knowledge has imposed—not using drink as a crutch for work, for instance, or even in connection with certain active forms of pleasure like fishing and hunting, which, for me at any rate, it blurs and takes the edge from. I lay off entirely for a spell sometimes, to prove to myself I still can or to help in losing weight, and I know that if a doctor I respected told me to do so I could drop the whole business for good. But I admit I do pray with muted Whiskeypalian piety that this will not come to pass.

I used to have an older friend who during a time of debt and other big personal troubles came to lean on whiskey quite heavily, without ever letting it get out of hand as far as anyone else could tell. When the troubles were finally behind him he took a good look at himself and decided the stuff had clamped down too hard, and so one day swore off—which, he being the man that he was, meant quitting for life. Eight or ten years later he was put in the hospital to undergo an operation that nobody seemed to believe he’d survive—though, as it turned out, he did—and I went around to see him a day or so before the thing was scheduled. He was a reserved man by nature, a listener rather than a talker, but the sedatives they’d given him, and perhaps his situation, had him in a thoughtful and not unhappy and almost garrulous mood. We spoke of matters I don’t think we’d ever discussed in the past, basic matters for the most part—the ways of men with women and of women with men, the pitfalls of being born Southern, friendship, ambition, even immortality—in an easy and inquiring way, and he was far broader in his thinking than I’d known. I remember feeling angry with myself for not having seen this long before.

Then he said, “I want to tell you something about John Barleycorn.”

I was leading a bachelor life at the time, not a very gaudy one, and imagined someone had given him to believe I was drinking too much, which wasn’t true. And remembering that long unremitting abstention of his, I supposed he was going to give me a lecture on the subject, as is some abstainers’ unfortunate wont. I hadn’t thought him to be of that ilk, but with things looking the way they did for him at that point, he had a right to moralize if he liked. Therefore I resigned myself to it and said, “What’s that?”

“Old John Barleycorn,” he said with a wide, crooked, reminiscent smile, “was the best friend I ever had.”

- More About:

- Libations

- Wine

- Longreads

- Beer

- John Graves