Houston’s status as the Energy Capital of the World is indisputable. So much so, that it’s hard to even understand how it ascended to that level—it just is. But if you roll back the clock to the beginning of the twentieth century, its future in black gold was hardly assured.

After all, the Spindletop gusher erupted in 1901 near Beaumont, about 85 miles to the east. Despite the Corsicana field and others elsewhere in Navarro County that preceded it, Spindletop was the true birthplace of the boom, and it was quickly followed by others in Hardin County, near Beaumont.

With its Neches River port downtown and two other deepwater harbors in Sabine Pass and Port Arthur only a dozen or so miles away, Beaumont didn’t need to dig a ship channel to bring in supplies or export crude. Indeed, for a couple of years after the Spindletop gusher, it looked like Beaumont was well on its way to establishing itself as the epicenter of Texas’s oil boom. Deflated Houston city leaders at the time acknowledged what to them was a sad fact: they resorted to billing Houston pathetically as nothing more than “The Gateway to Beaumont.”

And that’s not to mention the other competitors that followed. Between 1901 and 1929, other boomtowns erupted all over Texas: Corsicana, Ranger, Borger, Odessa, Kilgore. So how did Houston become the vast megapolis that it is today while all the others sizzled briefly for a time and then settled back into large town or small city status? The answer: one man’s shrewd business acumen and the multi-decade gargantuan feat of human willpower that is the Houston Ship Channel.

“I am not of the opinion that any other city other than Beaumont had a shot at it,” says Houston historian and author Mike Vance. “To me the turning point was Jesse Jones basically buying a building and essentially giving it to the Texas Company.”

In 1907, Jones emerged from a nationwide financial panic relatively unscathed. With rare cash in hand, the 33-year-old wheeler-dealer went on a building spree in Houston, erecting and then expanding the swanky Bristol Hotel, giving the Houston Chronicle a ten-story headquarters in exchange for a half-interest in the city’s leading information source, and building another ten-story skyscraper on spec. Ultimately, he planned to use it to extract Joseph Cullinan’s Texas Company—which you probably know now as Texaco—out of the Golden Triangle and move it to what was then known as the Magnolia City.

Sweeter deals have seldom been tabled: Jones offered the Texas Company a brand-new building for a mere $2,000 a month. And Jones would have to offer such seductive inducements—Cullinan was, at the time, deeply entrenched in Beaumont. As Vance writes, by 1908, the Texas Company had tank farms and a refinery in the area, one linked by a pipeline to both the Sour Lake and Humble fields, not to mention an asphalt factory in Port Neches.

But in the end, Jones’s deal proved too enticing for Cullinan to pass up. “Houston seems to me to be the coming center of the oil business,” Cullinan had written to an associate in 1905. He was right. And largely thanks to him, Houston would never be the same.

“[The Texas Company] was the big dog, and others followed,” Vance says, noting that the Texas Company’s move to Houston coincided with a couple of prosperous oil fields near Houston. “The Humble field and the Goose Creek field were both bigger than what Beaumont had, and they were both right here in Harris County.”

The Harris County fields goosed the industry’s momentum. Soon modern-day Texaco’s forerunner would would be joined by Humble Oil (which eventually became Exxon), and many, many others. “Out of Humble there were a lot more fortunes made,” Vance says. “It just got to be where you couldn’t ignore Houston. All the Humble guys were here, and all the smaller companies. There were 89 oil companies in the Houston phone book 100 years ago. And then you had all the tool companies and pipeline companies—it was a gold rush mentality with a modern twist.”

Cushy as the Jones deal was, it’s unlikely Cullinan would have bit had he not known that the Houston Ship Channel as we know it today would open in 1914, just a few years after he moved to Houston. (Vance points out that the 1914 date is somewhat arbitrary, and that Houston’s port facilities were much farther along by 1908 than most people understand today.) Its evolution has brought to reality the then-outlandish claim of John and Augustus Allen—the brothers who founded the city—that Houston would one day “command the trade of the largest and richest portions” of the state and become the “the great interior commercial emporium of Texas,” even if it finally did so in an industry they couldn’t conceive of in 1837.

Of all the Texas oil boomtowns, Houston—as the largest of them all—was best able to accommodate the stratospheric population growth that came in with the gushers. City services in the other towns were unable to keep pace with the throngs of fortune- and job-seekers streaming in daily. People lived in shacks or tents without sewage or running water. Staples were expensive.

Take Beaumont, for example, a town with more advantages than most of the other oilfield boomtowns. Its population of almost 10,000 made it practically a metropolis pre-Spindletop. Nevertheless, according to oil field historian H.P. Nichols (as quoted on podcast The Dollop), post-Spindletop Beaumont could only offer “soupy” drinking water that “smelled like fish.” Even worse, drinking it gave people what became known as “a case of the Beaumonts.”

“If the name of your town becomes synonymous with diarrhea, that’s a bad town,” said one of the Dollop’s co-hosts. And to make matters worse, enterprising wheeler-dealers built outhouses and charged those suffering the Beaumonts the princely sum of 50 cents for a seat on those rickety thrones.

Geologist, legendary wildcatter and Beaumont native Michel Halbouty believed the city of his birth did as much to push the industry to Houston as Houston did to pull it west. Speaking bluntly toward the end of his long life, Halbouty told Upstream that “Beaumont didn’t have the know-how to do anything like that. Those people in Beaumont are half-dead—and I was born in Beaumont…. The people there didn’t want [oil exploration].” Vance has a more calculated explanation for the reason that Beaumont isn’t the Energy Capital of the World: “Houston stole it from Beaumont.”

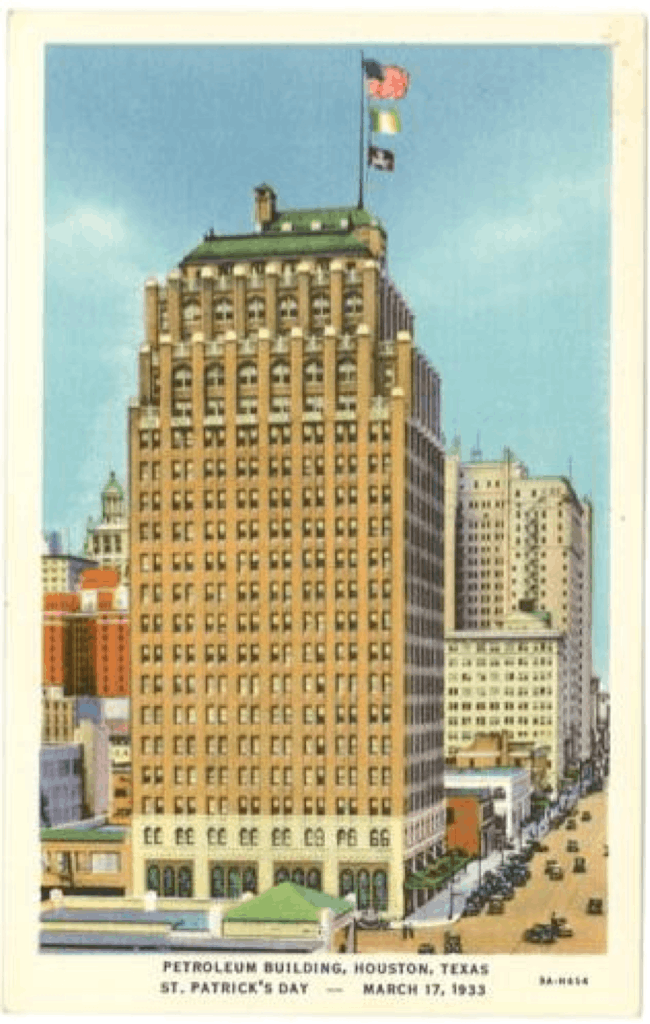

Maybe that partially explains the piratical displays of Joseph Cullinan. Born in Pennsylvania and proud of his Irish ancestry, the Texas Company chieftain would hoist three flags each Saint Patrick’s Day: he flew an Irish tricolor at his Houston home, and raised a Jolly Roger (beneath the Irish and American flags) from atop the Petroleum Building downtown, “as a warning … that liberty is a right and not a privilege.”

No more Houstonian words were ever spoken.

- More About:

- Energy