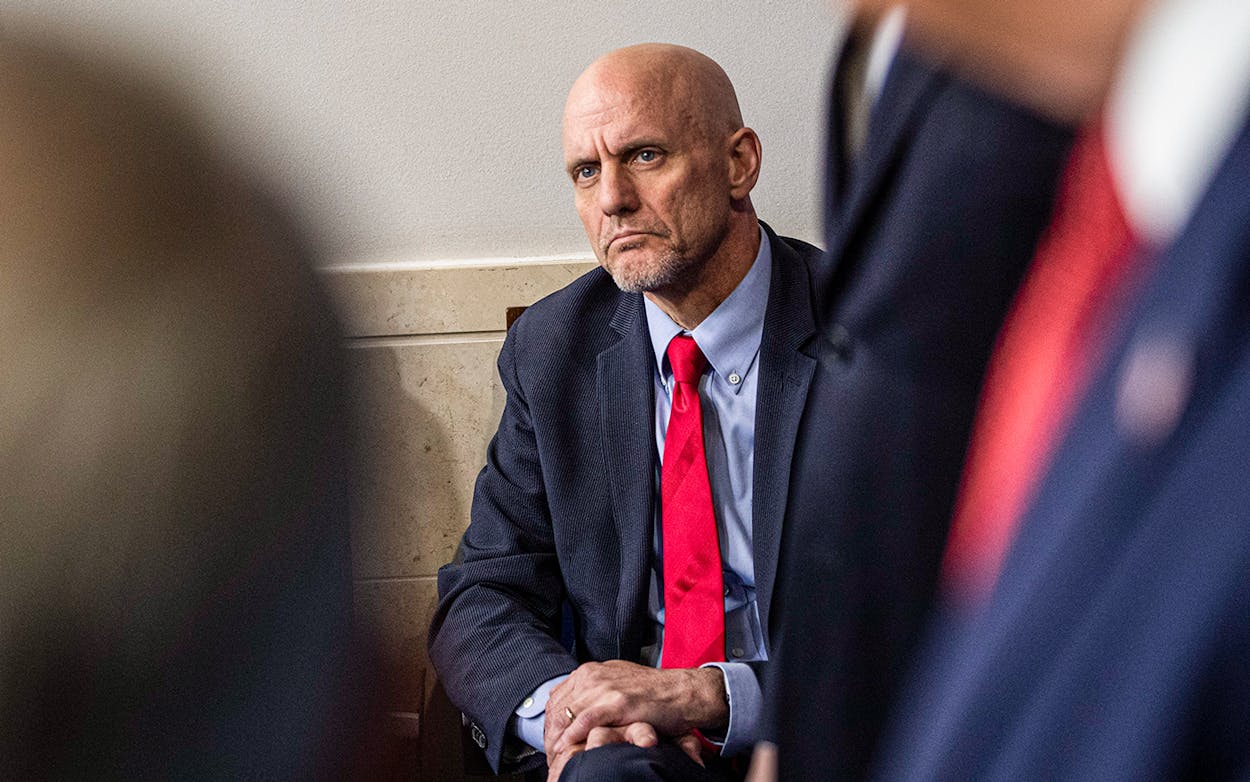

On the morning of March 19, as a pandemic paralyzed American life and cratered the global economy, Dr. Stephen Hahn stepped before the White House press corps and corrected his boss. The commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration was far from the first federal official to have to do as much. He wasn’t even the first that month, in that room.

President Donald Trump had led off that morning’s Coronavirus Task Force briefing by boasting of his efforts to “slash red tape like nobody has ever done” in order to enable rapid development of treatments. He spoke of a newly launched vaccine trial that the FDA had fast-tracked and turned his promotional talents to touting two drugs—an antimalarial medication in use for decades and an experimental antiviral—as already proven to be effective in fighting COVID-19.

“Normally the FDA would take a long time to approve something like that, and it was approved very, very quickly,” Trump said. “Those are two that are out now, essentially approved for prescribed use, and I think it’s going to be very exciting.”

Next up at the microphone, Hahn began his remarks by praising the president’s leadership before making plain that those drugs had not, in fact, been approved. They were merely being tested against COVID-19.

“What’s also important is not to provide false hope,” he said, his sober assessment in marked contrast to the words of the president. “We may have the right drug, but it might not be in the appropriate dosage form right now, and it might do more harm than good.” He assured the public that the agency, while doing everything it could to speed along the process, would ensure the safety of any drugs before allowing their widespread use against the coronavirus.

The moment suggested that Hahn was the sort of calming, competent crisis manager who former colleagues say he had been in his previous position as a radiation oncologist and chief medical executive at the world-renowned MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. There he was widely credited with restoring the institution to sound financial footing and repairing what had become a distrustful relationship between hospital leadership and faculty.

It remains to be seen whether he can achieve similar results at the FDA. Trump didn’t stop publicly promoting the use of one of the drugs—hydroxychloroquine—that he’d pushed at the March 19 briefing. And just nine days later, the FDA signed on to the use of it and the related drug chloroquine in treating COVID-19 patients. Though the agency’s guidance encouraged that use to take place within clinical trials, supplies of the drugs from the Strategic National Stockpile were made available for doctors to prescribe.

An FDA spokesperson denied that this decision had been reached at the president’s behest, but some observers worried that the agency had allowed itself to be unduly influenced. It was, former FDA commissioner Margaret Hamburg told Science magazine, “a step away from scientific rigor, to a system that is much more subject to all kinds of interference, from wishful thinking to frank political and economic motivations.”

Just this week, reports emerged of serious heart rhythm problems among COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine. The agency issued a new warning against use of the drugs outside a hospital setting.

Only a few months into Hahn’s tenure at the FDA, COVID-19 had asserted itself as the defining issue of his job, come what may. The early results suggest he hasn’t yet mastered the levers of Washington power.

Stephen Hahn doesn’t know exactly how he caught Donald Trump’s eye. His dearth of government experience was atypical of those selected in recent decades to lead the agency. The previous commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, enjoyed bipartisan praise for his roughly two years in charge, but he’d come to the job after two prior FDA stints.

“You can see what a difference that made, with Gottlieb being able to hit the ground running—knowing how to work with the staff, knowing how to work with Congress,” says Mark McClellan, FDA commissioner during the George W. Bush administration and now head of Duke University’s Margolis Center on Health Policy and a senior policy advisor at the UT Dell Medical School. “That’s a lot to learn if you haven’t done it before.”

Hahn admits to being “a little shocked” by his nomination to the post last November following a months-long process. News outlets were left to speculate about the reasons he was chosen over acting commissioner Ned Sharpless, who had received public endorsements from several former FDA commissioners and dozens of public health interest groups.

The Washington press implied that Hahn’s history of giving to Republican political candidates was an advantage over Sharpless, who had given mostly to Democrats. (A White House spokesman would only tell Texas Monthly that the administration never comments on personnel issues.)

Even if his political leanings factored into the nomination, Hahn’s more than thirty-year career leading divisions at two highly respected medical institutions—MD Anderson and the University of Pennsylvania—suggests he’s abundantly qualified for the post. He’s overseen thousands of clinical trials, making him well-acquainted with FDA approval processes for drugs and medical devices.

A 1980 Rice University graduate, Hahn grew up in a large Catholic family in the Philadelphia area. He earned his medical degree at Temple University and was an internal medicine resident at the University of California San Francisco before completing a fellowship and residency at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

“People told me over and over again, ‘Don’t go into oncology; it’s depressing.’ It wasn’t depressing by any stretch of the imagination because people are scared—people need your help,” Hahn says. “You want the outcome to be outstanding, but of course, it isn’t always. But how you help people face that journey is incredibly compelling as a physician, and I will always treasure those experiences with my patients.”

Radiation oncology became his specialty, with his research interests including the molecular causes of tumors and the potential of proton therapy—the use of positively charged subatomic particles, rather than X-rays, in radiation treatments—to improve outcomes. He joined Penn’s medical school as an assistant professor in 1996 and rose to chair its radiation oncology department from 2005 until he went to MD Anderson in January 2015.

Two years later, the UT system’s then-chancellor, William McRaven, asked Hahn to take on a newly created position, chief operating officer, to deal with a fiscal crisis. Facing projected annual operating losses of as much as $450 million, the hospital had been forced to eliminate about a thousand positions. So, in February 2017, Hahn joined MD Anderson’s executive ranks.

Ronald DePinho, whose five years as president were beset by ethical controversies and financial difficulties, resigned a month later. That left even more responsibility for restoring the hospital’s finances on Hahn’s shoulders. The operational changes he instituted worked. Fiscal 2017 ended with an operating loss of $23.4 million, significantly better than the earlier dire projections. The next two years saw MD Anderson return to the black, including $231.9 million in operating income for 2019.

Peter Pisters, who became president of MD Anderson in December 2017, is effusive in his praise of the leadership Hahn demonstrated as the institution navigated a pair of controversies last year. When three researchers of Chinese ancestry were fired for violating federal funding rules, some faculty members expressed concerns that the dismissed researchers had been racially profiled. Hahn addressed those concerns head-on in meetings with employees throughout the institution.

“He has a unique ability to demonstrate all the principles of active listening,” Pisters says. “When people were meeting with Steve, they knew that he was literally leaning in. He was listening to their point of view. He was demonstrating that he really cared.”

A more serious blow during Hahn’s tenure came from an inspection by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services prompted by the death of a 23-year-old woman because of a tainted blood transfusion. Inspectors last summer found serious violations and determined that there had been at least two other preventable patient deaths.

MD Anderson lost its “deemed status,” meaning it failed to meet minimal requirements to receive Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements. Hahn, who was in charge of all clinical operations, was instrumental in crafting the institution’s corrective plan, though by the time deemed status was restored in January, he was already working at the FDA’s headquarters, in Silver Spring, Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C., as the agency’s twenty-fourth commissioner.

At his confirmation hearing last November before the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, Hahn bobbed and weaved during attempts to pin down his positions on controversial issues, as if he were a Capitol Hill pro. He’d clearly been well coached, given how he recited over and over the same bland answer to senators’ questions—a general commitment that he would seek “data-driven and balanced solutions that are congruent with the law.”

When it came her turn to speak, Democratic senator Tina Smith of Minnesota told Hahn she was not so sure he should count himself fortunate if confirmed by the Senate. “This looks like a really hard job to me,” she said. “You really are going to be between a rock and a hard place. You’ve said quite a few times—and I believe you—that you are a physician and scientist ruled by science and data and the law, and yet colleagues on both sides of the aisle have acknowledged that in many circumstances there are many political pressures, political influence that’s going to be brought to bear on you.”

Hahn sought to assure her that he would stand up to undue influence. “Throughout my career, as you probably know from my record, I’ve found myself in situations of leadership where making tough calls needs to be done that aren’t popular, that aren’t being made in the best interest of Steve Hahn but in the best interest of the people that I’m helping, the patients,” he said. “Senator, I can promise you that I will follow that.”

He easily won approval by the full Senate and was sworn in as commissioner on December 19, shortly before the first news of a novel coronavirus outbreak in China. The rapidly escalating scale of the crisis didn’t allow the new commissioner much time to contend with the job’s steep learning curve. As confirmed virus cases mounted across the United States, Hahn became one of the faces of the administration’s lackluster response.

Public health experts uniformly describe widespread testing for the coronavirus as vital to containing the spread of infection. Yet for weeks after Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar’s January 31 declaration of a national public health emergency, only the CDC and a handful of state labs were approved to test patients. Commercial and academic labs working to deploy their own diagnostic tests complained that the FDA’s slow-moving, punishingly bureaucratic approval process was a significant roadblock. For instance, one virologist at the University of Washington told the Washington Post that he spent more than one hundred hours filling out paperwork and submitting an application via email to the FDA, only to then be told that he also needed to burn the electronic documents onto a hard disk and mail that to the agency’s headquarters. Meanwhile, the test he’d developed went unused.

It wasn’t until February 29 that the FDA loosened regulations to allow some certified labs to begin testing patients for COVID-19 before they had officially received an emergency use authorization from the agency. It was nearly two more weeks before the first test developed by a private lab was approved.

Testing wasn’t the only arena in which the FDA appeared too inflexible in confronting the crisis. As hospitals overrun by COVID-19 patients saw supplies of personal protective equipment for doctors and nurses dwindle to dangerously insufficient levels, Ohio-based Battelle developed a decontamination system to allow the safe reuse of masks, gloves, and goggles. But the FDA’s initial March 29 emergency authorization of the device limited its use to Battelle’s own Columbus headquarters. It took an appeal by Ohio governor Mike DeWine to Trump, who tweeted “@FDA must move quickly!” before Battelle received the agency’s go-ahead to ship the devices to hospitals and clinics.

Still, Hahn has repeatedly pushed back at criticism about the caution with which the FDA proceeds even in the face of an emergency. He insists that the agency issues approvals as quickly as it can while maintaining its duty to safeguard the public.

Jane Henney, FDA commissioner during the last two years of the Clinton administration, is sympathetic to Hahn’s point of view about adhering to the regulations. “The folks there don’t put hurdles in place that aren’t needed,” she says. “There is nothing worse than getting a diagnostic test out and available for the public when it potentially does not work. Then you’re left with worse than nothing.”

Meanwhile, Gottlieb has been a frequent guest on national TV news and has posted to Twitter steadily about the government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis. While he has praised some actions of the Trump administration, he has also said that testing by private labs should have been ramped up faster. “I certainly regret leaving now,” he told Time magazine. “It tortures me that I’m not there helping the agency through this.”

The same March day that President Trump gave the American people the false impression that something like miracle drugs were on the way, Gottlieb and McClellan jointly issued a paper urging the FDA to take more aggressive action. They suggested the formation of two task forces to accelerate the pace of developing coronavirus tests with quicker results and to speed along antiviral drug development.

“Nobody’s done enough to address this crisis, right? It’s an unprecedented pandemic, and I think we’re still struggling though it in every step,” McClellan says about whether Hahn has used the full power of his office in combating the coronavirus. “There is no perfect preparation for this job. This is a complicated job under the best of circumstances, and this is definitely not the best of circumstances.”

- More About:

- Health

- Donald Trump

- Washington

- Houston