There were many ways to die underground during the Ice Age in Central Texas. Sinkholes in the karst hills, slick-sided and treacherous, swallowed unwary animals. Saber-toothed cats dragged their prey back to underground dens, leaving behind generations of bones, including those of the cats themselves, lying beside their victims in the dark. Treacherous paths in the depths, far from the sun, waited for those with the urge to explore.

In 1960, that animal urge to slip underground led Orion Knox Jr. and three other St. Mary’s University students—all avid cavers—to go looking for caves. With the owners’ permission, they explored the Wuest family ranch in Comal County, 25 miles north of San Antonio. There the group discovered a passage at the bottom of a sinkhole, under the shadow of a great limestone bridge.

Over the course of several expeditions, with ropes around their waists, they slithered underground for more than a mile, through tight walls and sucking mud. In 1963, exploring far from the passages that would later be open for public tours, they found holes leading into two deep pits, 120 feet below the main shaft. The students nicknamed the two pits the Dungeon and the Inferno. Rappelling down into the former, Knox discovered that he and his friends had not been not the first to descend. Embedded amid the ooze and stone were the fossilized bones of a wildcat.

While the cavern had been a spectacular discovery, the bones were a rare and intriguing find. “Nobody could say how old [the wildcat] was,” says John Moretti, a paleontologist and doctoral candidate at UT. “It didn’t have other animals or sediment associated with it. There weren’t a lot of other clues.” In 1963, a paleontologist from the University of Texas came out to collect some of the wildcat remains.

Knox quit college to help the Wuest family develop the cave, which opened in 1964 as Natural Bridge Caverns, still a beloved show cave and part of the largest known commercial cavern system in the state. Meanwhile, researchers studied fossils from the region’s other caverns to piece together how the state’s ecosystems took shape. The wildcat bones sat in storage, a curiosity. But in 2021, cavers discovered more wildcat remains down in the black. Researchers are just now beginning to unlock their secrets. At the beginning of this year, Moretti and eight other scientists gathered at Natural Bridge Caverns, strapped on head lamps, and descended into the Dungeon that Knox had first visited more than sixty years earlier. Their findings will help reveal how these cats fit into the broader story of Texas ecosystems—and they could begin to unravel an ancient mystery.

Many of the bones found in Texas caves find their final destinations in the cabinets of UT’s Jackson School Museum of Earth History, a drab, three-story building on the school’s satellite J. J. Pickle Research Campus, in North Austin. Metal doors in a long row open onto wooden shelves, each containing the remnants of a vanished life: a sabercat kitten, deer limb bones, matchboxes full of rats, and small glass vials of sediment samples and microfossils.

These relics are Moretti’s domain. Lanky and jovial, Moretti specializes in the question of how Texas’s animal ecosystems have changed over the last several million years. He works with fossils collected by previous generations of paleontologists from Central Texas caves; in aggregate, these remains offer an unusually clear 15,000-year record. Some spots, like Bexar County’s Friesenhahn Cave, preserve Ice Age megafauna, including Homotherium sabercats and their prey, juvenile Columbian mammoths. Another site, Kerr County’s Hall’s Cave, has yielded at least 62 species of mammals and at least 48 species of nonmammals.

“Caves are a really special preservational setting,” Moretti explains as he opens cabinets. They’re essentially climate-controlled underground storage containers, preserving collagen and DNA lost to the elements elsewhere. As a result, remains found in caves can often yield vital information not available from skeletons left exposed on the surface.

The earliest cave deposits, from about 18,000 years ago, record a Hill Country that looked considerably different. Back then, this part of Texas was a wetter, wilder mosaic of timber forest and savannah. Mammoths, multiple species of horse and camel, mountain deer, and one-ton bison grazed the tall grass. Dire wolves, cave lions, jaguars, and two species of sabercat prowled the canyons and plains. Skulking in the shadows were coyotes and smaller predators.

By 10,000 years ago, however, catastrophe had struck. The majority of the big herbivores disappeared, leaving behind only bison, pronghorn, and deer, and other smaller species. Most big predators, including the sabercats, vanished as well. The overall result was a simpler, more barren ecosystem, says Felisa Smith, a University of New Mexico paleontologist who has done fieldwork at Hall’s Cave. Bones preserved there hold stable isotopes—accumulations of nitrogen and other elements based on diet.

“Between the loss of large herbivores that act as ecosystem engineers and increasing aridity,” Smith says, “you get the landscape we see today,” one where multiple species niches—such as those of big predators or large prey—remain empty, leaving a poorer, more simple ecosystem.

One possible factor in these Ice Age extinctions was the appearance of humans, who began reshaping the ecosystem through hunting and fire regimes. Climatic shifts may explain the disappearance of other, smaller animals, many of which persist elsewhere in the country—such as chipmunks and bog lemmings. “It’s a great hypothesis and explains a lot of what we see in the record,” Moretti says. “But it’s really hard to test—we know what animals were here, but we can’t always pin down exactly when.”

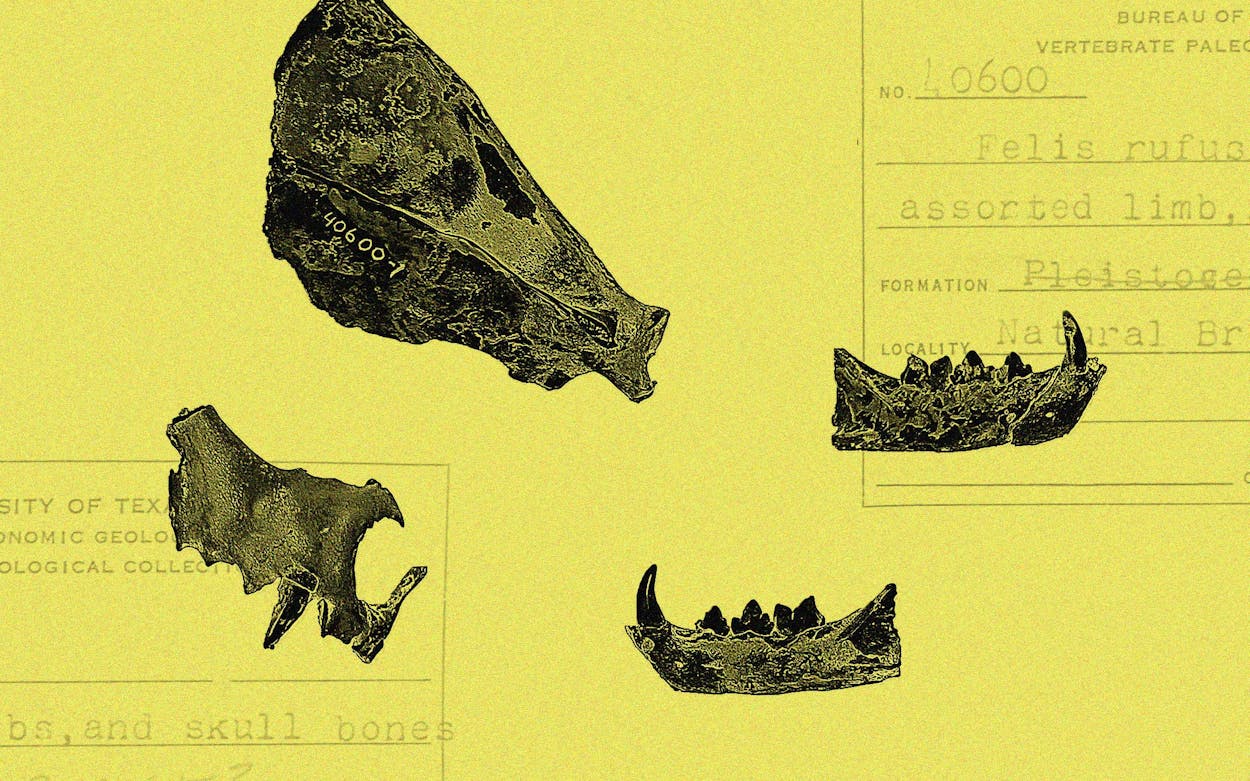

The wildcat of Natural Bridge Caverns is an excellent example of this uncertainty. Moretti shows me the remains, a collection of scraps from an animal about the size of a bobcat. One bone still sits entombed in flowstone, or mineral layers deposited in caves by flowing water, like a macabre pastry topping. “Some of this stuff looks like doughnut icing,” Moretti says cheerfully. “You get me in the right mood in the cave, and I get hungry.”

The UT grad student who originally collected the wildcat assumed the remains belonged to a bobcat. Later scientists floated other possibilities, such as a margay—a small climbing wildcat now found only in Latin America—or the long-tailed, secretive jaguarundi. According to Moretti, an identification was hard to make because wildcat bones don’t vary much from species to species. Equally unclear was the animal’s age—anywhere from 20,000 to 2,000 years old. When UT paleontologists first retrieved the bones in 1963, few good techniques existed to date isolated remains: by the time carbon dating could be employed, Moretti says, the fossils had been contaminated by too much handling. The wildcat bones were a dead end.

That changed in 2021, when Brad Wuest, president and CEO of Natural Bridge Caverns, took a survey team into the depths of the Dungeon. In the years since 1960, when Knox and his friends explored the caves, the Wuest family had converted a chunk of the system into a full-fledged “show cave,” complete with concrete pathways, artificial lighting, and a public tour that culminated in a huge room full of spectacular formations. But the farther reaches of the cavern—the “wild cave,” which lies far from the public tour—had seldom been visited, and the original maps had been lost.

Wuest and his team squeezed their way back into these depths with the intent of recharting the vertical chambers. Each could only be accessed through a narrow tube full of shin-deep mud, complete with funnel-like openings onto sixty-foot drops. And just as Knox had, decades earlier, Wuest found bones waiting at the bottom of the Dungeon.

He guessed immediately that this might be the rest of the skeleton from the wildcat UT had collected in 1963. Upon returning to the surface, he began asking around for a paleontologist—and was connected through the cavers’ network with Moretti. These bones could now be subjected to a full battery of tests, their origins unpacked.

When Moretti came out to visit the Dungeon in April 2022, the cave had already yielded more treasures. In December 2021, another significant set of wildcat bones turned up in the Inferno room. But the more remarkable find had appeared a week before, when Wuest led another team of biologists back into the depths to survey for cave organisms. Jean Krejca, the team’s lead biologist, lost the sole of her boot in the muddy quagmire near the pits. After replacing it, she returned to find the rest of the team gone. Waiting for them to return, she played her head lamp over the thick clay mud. Abruptly, she realized she was looking at little cat tracks.

“It’s a dark, narrow, muck-filled tunnel. Nobody ever thinks to look for these sorts of things,” Moretti says. “People have probably been walking over and destroying them since 1963.”

While it’s conceivable that the prints were laid down at a different time from the bones, the possibility of a connection is tantalizing. “There are tracks that continue between the pitfall into the Inferno room and the pitfall into the Dungeon room,” Moretti said. Some of the prints seem to cross over each other, or wander up the slopes of the walls, as if casting about blindly in the dark. “Then there’s no more tracks. And there’s a cat in both rooms.”

Natural Bridge Caverns, Moretti and Wuest agreed, had offered them a tremendous opportunity: the cave now clearly held the remnant of the original skeleton, as well as the remains of another, and a trackway that might connect them. Now it was time to go and get the bones out.

On the bright morning of January 10—coincidentally, just ten days after Knox died in Austin at the age of 81—Moretti, Wuest, and a team of eight other cavers, as well as a few journalists, assembled in an out-of-the-way part of Natural Bridge Caverns. Outfitted in elbow pads, helmets, and harnesses, they carted along boxes and tools to excavate the remains.

The team entered through the back exit, descending down a steep, concrete-paved tunnel into the humid, warm depths of the cave. Wuest led a prayer. “I pray for the success of this expedition,” he said, head bowed. “I pray we’re able to learn more about these small cats, get some radiocarbon dating, and start to unravel this amazing mystery. In Jesus’s name, Amen.”

With that, the team picked its way down slopes of slippery flowstone. Entering the tunnel, the ceiling dropped, forcing everyone to crouch amid the deep mud, then to haul themselves on their stomachs through a narrow, claustrophobic stretch nicknamed—in typical cave fashion—the “birthing canal.” Moisture dripped down walls of thick limestone clay. Ooze clutched at boots. Beyond the glow of head lamps, the blackness was a solid thing.

Only the expedition members proceeded on into the Dungeon and Inferno rooms, strapping into a permanent rope fixture and rappelling down with their boxes and tools. The descent requires specialized training, and the section of tunnel leading into the pits is slippery and potentially dangerous, even for experienced cavers. It’s hard not to recall that for at least two animals, it proved lethal.

The scientists spent two days working in the Inferno room, collecting bones that had settled amid the cracks between boulders and cave formations. They ended up collecting a good chunk of the animal, including parts of its jaw and an inner ear bone—“the best bone for us to sample for DNA and radiocarbon dating,” Moretti says. Another day’s work went into collecting the remains in the Dungeon room. All were packed away in bulky cases and hauled back up on ropes before being negotiated out of the narrow passage to the surface.

The wildcat bones now rest in the cabinets of the UT Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. The pieces the team collected from the Dungeon—including chunks of flowstone that once held bones—fit perfectly with the remains from 1963, Moretti says. “It’s a really nice circle back to Orion Knox. Sixty years later, and we got the rest of the cat that he found when he first entered the Dungeon. It feels like we completed what they started.”

Now the real research can begin. Collagen in the inner ear bone found in the Inferno room will help determine the cat’s age. Through ancient DNA sampled from the skeletons, Moretti says, “There’s an opportunity to test these different hypotheses—Are they bobcats? Margay? Jaguarundi?—in a way we couldn’t before.” Once researchers know what the cats are, the remains might also be key in helping to identify other ancient wildcat finds.

Locking down the wildcats’ identities and ages would also help establish what role they played in Central Texas’s vanished ecosystems. Margay fossils have been collected in the state, particularly along the Sabine River in Orange County. Scientists disagree about whether the elusive jaguarundi has ever lived in Texas. But if it did—as Moretti believes, and as these skeletons might prove—its disappearance tracks with the other great ecological shift in Central Texas: the arrival of European settler-colonists and their steady conversion of native-managed habitat to cattle land. Bears and wolves—whose historical remains still turn up in caves—were exterminated from much of Texas by the 1950s and 1970s, respectively. The last jaguars hung on until the 1940s; then they were gone, too. “You see a further simplification of the animal community: a reduction in diversity,” Moretti says. “Some of these European animals are pushing out other things.”

Cave fossils like those found in Natural Bridge Caverns tell us not just about animal diversity in the past, but also how our modern animal community took shape and what it’s lost. A clearer vision of those histories helps researchers predict the impact of changing environments, Moretti says, especially amid further climatic change. “It helps us figure out where we’re going, and how these animals respond to the future, in terms of us directly impacting ecosystems.”

But there’s another tale here as well, more intimate and worth considering on its own terms. Some of the cat tracks are mere smudges in the mud and flowstone. Others are startlingly clear, as if the animal only just passed by. The tracks drive home an easily forgotten point: these animals—now resting in boxes and bound for an afterlife of metal cabinets—were once alive. Once they prowled, purred, and breathed.

What happened to them? Did they enter the cave at roughly the same time, or was it hundreds of years apart? How did they end up at the bottoms of the Inferno and Dungeon pits, a mile back and 120 feet down through impenetrable dark? Wuest and Moretti have recently identified a possible entry point: a now-sealed shaft nicknamed the Attic, leading down to the remains of long-vanished Ice Age bat colonies.

Perhaps, Wuest suggests, the cats came in chasing prey and got lost in the labyrinthine passageways. Or perhaps they simply did what animals occasionally do, from wildcats to cavers like Orion Knox: they saw a hole, and they decided to venture inside.

- More About:

- Critters

- San Antonio