One woman hid her daughter’s pink hair tie inside her sports bra. Others kept floral-print postage stamps they’d torn off letters from home and glitter shaken from greeting cards. For many incarcerated women, these little stashes of fuchsia, silver, or yellow are against the rules, but worth the potential risk.

There are issues more pressing than greeting cards and glitter inside our prisons, such as the struggle to survive stifling Texas summers without air-conditioning or the fact that inmate deaths by suicide in the state continue to climb. Tiny pops of color that might be taken for granted on the outside, such as wildflower postage stamps, may seem frivolous, but they can pull someone out of a low moment or remind them to keep putting one foot in front of the other. A bright birthday card or a child’s drawing becomes a crucial form of connection, a boon for mental health. But according to former and current incarcerated women, implicit rules discourage decorations or bright colors of any kind, while explicit mandates limit brightly colored pieces of mail such as greeting cards.

“They keep things as bland as possible, and anything with color is definitely coveted,” says Lori Mellinger, 54, of the Texas prison system, which she started “cycling through” at age 26. She’s been out since 2015 and now lives in Lockhart, where she’s a member of the steering committee for Lioness, an Austin-based nonprofit that advocates for current and former female inmates across Texas. Her fellow Lioness cofounders, Maggie Luna, Marci Marie Simmons, and Jennifer Toon, lived with restrictions on artwork, greeting cards, and letters when they were each serving time, and their goal is to work with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to make sure women in places such as Gatesville’s maximum-security Mountain View Unit are treated in ways that will help them gain the confidence and skills they’ll need to reenter society.

In March 2020, in an effort to stop outsiders from smuggling in drug-laced paper, TDCJ implemented the Inspect 2 Protect program, which placed strict limits on what kind of correspondence inmates could receive and when. The restrictions meant that incarcerated Texans could only receive mail on plain white copy paper; mail with any color or texture was at risk of getting thrown out. Advocates, prisoners, and family members fought against the ban, and in 2021, TDCJ eased up on some rules. (TDCJ communications officer Robert Hurst says that the rate of illegal substances being discovered has not decreased under the correspondence policies.) Cards are now allowed three times per year, on Christmas, Mother’s Day, and Father’s Day. Last year, Toon and Mellinger took advantage of the two-week window for holiday mail and sent cheery cards featuring an image of a cute pig in a red Santa hat to three thousand incarcerated women.

According to Hurst, the amendments were made “to provide for the rehabilitation of inmates by assisting inmates in keeping in touch with family and friends.” Still, he says that “anything with excessive glitter or things similar” could cause a letter or card to get tossed before it reaches the inmate.

Toon grew up in East Texas and entered the juvenile system as a teenager, where she saw plenty of women punished for attempting to hold onto objects that reminded them of the outside. Over the twenty total years she served, she witnessed private, potentially risky moments, like the time a fellow inmate surreptitiously plucked a piece of red string off her child’s coat during visitation. Mellinger says that during her time inside, wardens and guards became stricter about bright colors, decorations, and greeting cards. She saw maintenance workers painting over a colorful hallway mural with gray paint. Her “biggest memory” of colorful contraband was a red ribbon that an inmate would occasionally wear in her hair. “She only wore it inside the dorm, not to the library or education or anywhere else outside of the dayroom doors,” says Mellinger. “We all knew which guards would give us grief.”

It might seem silly to think that a single red ribbon could actually mean something to a woman in prison, or that having that ribbon taken away could impact her mental health and recovery. But a February 2022 study of women’s experiences with mental health care in prison found that “there is a need for greater mental health support, including the need to enhance relationships between women and prison staff to promote positive mental health.”

Dr. Stephen Strakowski, associate vice president for regional mental health at Dell Medical School, is spearheading an effort to improve mental health support in Travis County jails. According to Strakowski, giving inmates access to tools or activities that can help them work through trauma, stimulate their creativity, or boost their overall mental health is imperative. “Staring at prison walls has proven to create recidivism, not reform,” he says.

“Psychologically, everything about prison is gloom and doom,” says Sandra Smith, the vice president of Via Hope, an Austin-based mental-health advocacy organization. “There’s a lightness that comes with being able to be creative or seeing things that give your mind a level of positive stimulation.” According to Smith, rules banning greeting cards or decorations are often “created by people who don’t understand what trauma looks like and how important something as simple as allowing folks to have greeting cards or colored pencils or adult coloring books can be.”

As drab as the prison walls were when Toon and Mellinger were incarcerated, there are some colorful signs of hope. The duo was surprised this past December when they saw pictures pop up on the Facebook page of TDCJ’s Hilltop/Mountain View Complex. Instead of bare walls in those photos, they witnessed dorms covered in holiday decorations—Christmas trees made of rolled-up green construction paper, DIY manger scenes crafted with cardboard paper-towel tubes, and makeshift fireplaces lit by bright orange streamers. Unless they had a “nice officer,” Toon says, there were no decorations of any type allowed when she and Mellinger were inside.

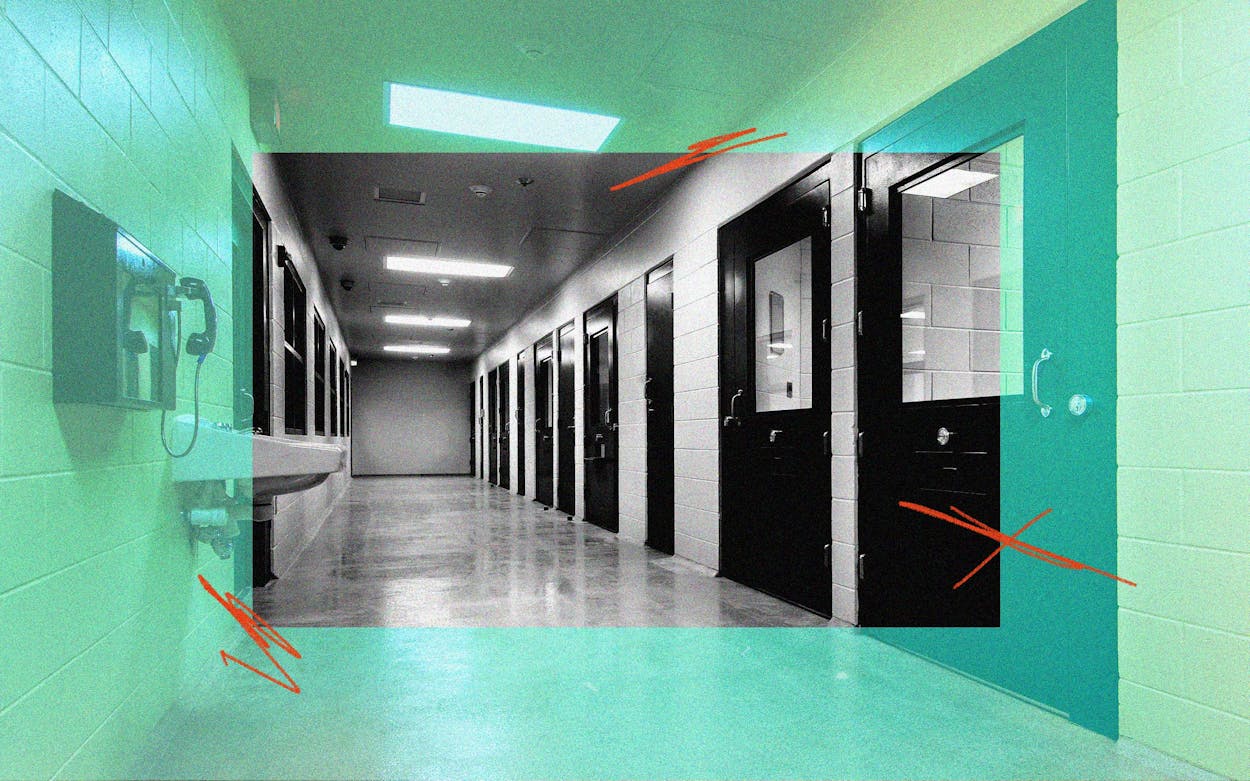

A few days after I met Toon and Mellinger, I drove up to Gatesville to visit two inmates currently serving time at the Mountain View Unit. I’d been instructed not to wear white, since that’s what the prisoners wear. The visiting area had more wall hangings and books than I expected, but that’s not to say the place was cheerful. There were chalkboards for children to draw on, a framed John Deere puzzle, and an Alice in Wonderland poster that read, “Which Wonderland Character Are You?”

I met with two inmates that day. First was Lizanna Ramirez, who originally met Toon when she was about 15, while they were both serving time in a juvenile facility. She’s now 44, with closely shorn black hair and a slight Texas drawl. I don’t ask, but she tells me she has a murder charge, and that her time is 75 years. Anataja Harris is a 38-year-old mother of four who works in the Braille facility making books for the blind. Harris hopes the skills she’s learning will lead to a guaranteed job when she gets out, so she can save up to one day open a clothing store. Until then, she keeps some photos and letters inside her white box of TCDJ-allowed personal items.

“You can’t have too many things out, so most of our personal property has to stay locked in that little white box,” says Harris. “Without those things, I couldn’t make it through.”

Like Harris, Ramirez isn’t allowed to hold onto many objects that could bring some color or brightness to her space, but she keeps a photo of her mom, grandfather, and niece on her table. “It keeps me focused,” she says. When I ask her about the holiday decorations the inmates were allowed to put up this past December, she perks up a little. “That was a good idea because people are sad that time of year,” she says. “That was a real positive thing.”

As Mellinger told me that day in Austin, “It’s our responsibility not to forget the women inside.” So she and her coworkers visit, they write advocacy letters, they attend hearings. Sometimes, when it’s allowed, they send a card with a little color to it.

A previous version of this story said no illegal substances had been found on inspected correspondence at TDCJ facilities, based on information from TDCJ communications officer Robert Hurst. Hurst later corrected that information to clarify that the amount of illegal drugs found did not decrease under the inspection policies. The story has been updated.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Prisons

- Austin