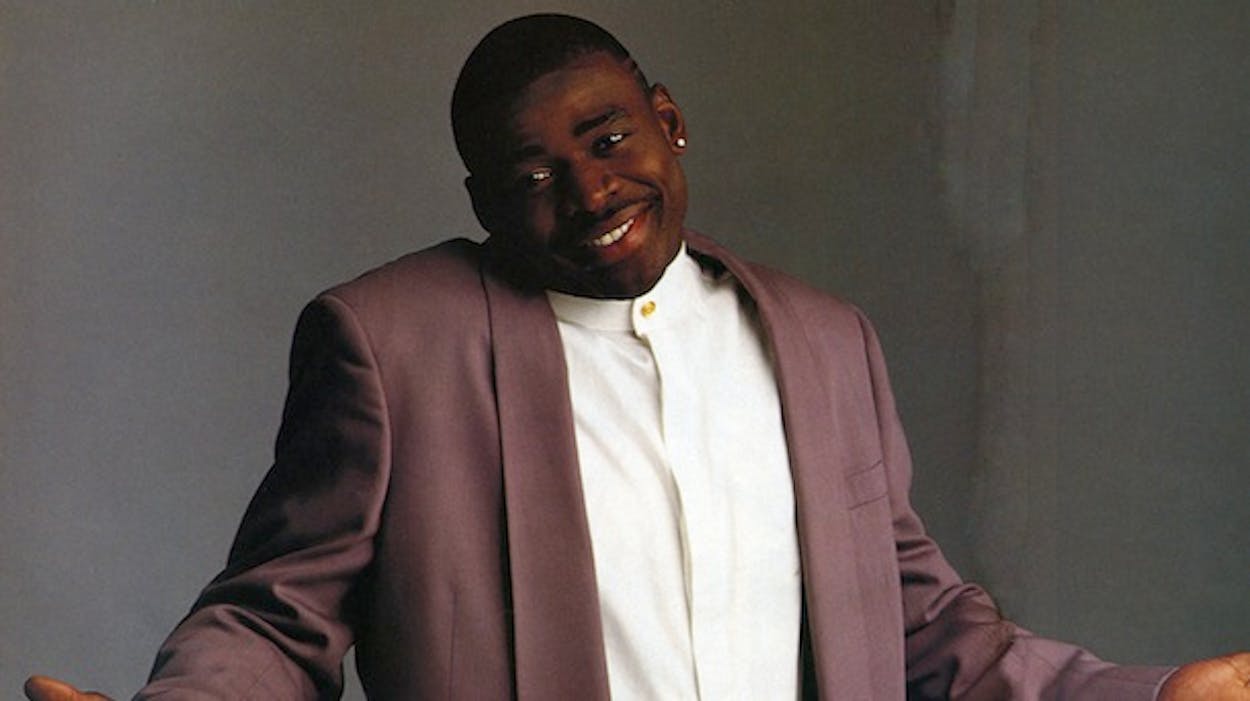

DALLAS FINALLY GOT ITS TRIAL OF THE CENTURY. It was a glorious farce, full of football stars, rogue cops, undercover agents posing as hit men, topless dancers arriving for court appearances in demure below-the-knee dresses, and angry lawyers debating whether African American men’s eyes are naturally bloodshot or only get that way after a night of drinking and drug use. At the center of the proceedings, of course, was Cowboys wide receiver and Super Bowl hero Michael Irvin, who came to court each day in sunglasses, alligator shoes, and tailored suits, one of which was lavender. “At least the trial was held in the summer,” a member of his entourage whispered, “so we didn’t have to worry about him showing up in that damned mink coat.”

It was Irvin’s full-length mink coat, which he wore along with a diamond stud earring for his grand jury appearance last spring, that let everybody know this wasn’t just a simple drug possession case; it was going to resemble a Las Vegas floor show. Courtroom employees oohed and ahhed at Irvin and the coat. One woman asked him to autograph her Bible. Irvin, who calls himself the Playmaker and parks his black Mercedes in the no-parking zone at the Cowboys’ training facility, basked in the attention. He considered himself untouchable—and why shouldn’t he?

On the night of March 4, police officers from the Dallas suburb of Irving didn’t arrest Irvin when they found him in a hotel room celebrating his thirtieth birthday with his buddy Alfredo Roberts (a former Cowboys lineman) and two topless dancers, Angela Beck and Jasmine Nabwangu. Party favors included 10.3 grams of cocaine and more than an ounce of marijuana, assorted drug paraphernalia, and sex toys. Although a glass cigar holder containing cocaine residue was found in a small bag belonging to Irvin, the officers arrested only Beck, a doe-eyed brunette who described herself as a self-employed model. According to later testimony, Beck took the rap and claimed that all the drugs were hers because Irvin had pulled her aside while police officers were still outside the room and promised he would treat her like a “princess.” Then Irvin greeted the officers and asked one of them, “Do you know who I am?” “I know who you are,” the officer replied.

To many people’s surprise, Mike Gillett, a lead prosecutor with the Dallas County district attorney’s office, decided that Irvin, the married father of two, needed to pay for his sordid night out. Gillett got felony indictments against Irvin and the two dancers. (Roberts went free because he could not be directly linked to any evidence.) If Irvin had pleaded guilty then, he no doubt would have walked away with a probated sentence and a four-game suspension by the NFL as a first-time violator of the league’s drug policy. The case would have been closed and Irvin could have gone on with his superstar life, albeit with fewer endorsements. But Irvin believed (and, according to one rumor that swept through town, was told by team owner Jerry Jones) that Cowboys don’t get convicted of crimes in Dallas. He wanted to plead not guilty, and what made Irvin such a hoot to watch on the field—his ability to talk trash to defensive backs as he escaped from their clutches, to spike the ball after scoring a touchdown and then throw off his helmet so the television cameras could get a close-up—was exactly what was going to make his trial so much fun to watch.

The national news media arrived to pronounce its outrage over Irvin. William Bennett, the former Secretary of Education and self-appointed national defender of values, went so far as to contend that Irvin and the Cowboys were “hurting this country’s morale.” To longtime Cowboys watchers, the fact that Irvin had become a symbol of a moral meltdown was a joke. Granted, he was an amazing player, one of the hardest-working members of the team and a delightful interview who could always be counted on for a good quote. But he was also well known as a scoundrel who had had his share of paternity suits and run-ins with women. After practices and games, he regularly strolled into the exclusive Men’s Club—which a disgusted Gillett called “a high-dog strip joint”—and paid white strippers who looked like former high school cheerleaders to dance for him. He often took those strippers to a hotel room or to what was known as the White House, a home near the team’s training facility where Cowboys players took women other than their wives or girlfriends.

But no one thought he had a drug problem—“Michael just got the drugs for the girls,” one acquaintance said—until three days after his grand jury appearance, when one of his running buddies agreed to let a Dallas television station put a hidden video camera in his car to film Irvin purchasing cocaine. The “friend,” a chubby and slightly pathetic hanger-on at the Cowboys’ training facility named Dennis Pedini, said he wanted to expose Irvin to help him get his life back in order. No doubt Pedini was also thrilled that he got some money and national television exposure on Hard Copy.

Then, tossing a barrel of lighter fluid on the fire, Dallas police chief Ben Click called a press conference during the middle of jury selection to announce that Dallas police officer Johnnie Hernandez, a five-year police veteran with an array of honors, had been arrested for solicitation of capital murder after giving $2,960 to an undercover agent from the Drug Enforcement Agency as a down payment for a “hit” on Irvin. Hernandez was the live-in boyfriend of Rachelle Smith, another brunette dancer from the Men’s Club, who had spent a few evenings in hotel rooms with Irvin and Angela Beck. In a secret appearance before the grand jury, Smith had ratted on Irvin, saying he told her the day after Beck’s arrest that the drugs in that hotel room were his. She also said Beck had told her she nearly had a heart attack when the police pulled a Hope diamond-size rock of crack cocaine that didn’t belong to her from her gym bag.

According to Smith, when Irvin heard about her grand jury appearance, he had Pedini and another crony take her to an apartment, where they forced her to strip and searched her clothes and every part of her body to see if she was hiding a listening or recording device. Irvin then demanded that she go back to the grand jury and recant her story. Smith said Irvin “kept on telling me that I shouldn’t be afraid of the DA’s office—I should be afraid of him, because he was more powerful.” She also claimed Irvin said that if she double-crossed him, “you’ll never see John [Johnnie Hernandez] or the light of day again, I promise you.”

How much seamier could this tale get? Plenty. The reason Hernandez was caught in the first place was because the Dallas Police Department was investigating the activities of allegedly dirty cops. The day after Hernandez’s arrest, rumors spread that he hadn’t wanted to kill Irvin for his threats against Smith. Well-known Dallas sportswriter Skip Bayless, the author of three books on the Cowboys, said on ESPN that sources had told him a hit had been ordered on Irvin because Irvin had made it clear that if he went down on drug charges, he would expose a scheme among local police officers to protect a drug and prostitution ring.

Like any professional sports franchise, the Cowboys had had their share of fallen heroes—from Hollywood Henderson succumbing to drugs to Lance Rentzel exposing his private parts in public. The team’s image was certainly not helped when lineman Nate Newton, defending the players’ White House, told one reporter, “We’ve got a little place over here where we’re running some whores in and out, trying to be responsible, and we’re criticized for that too.”

But the Irvin case was a real-life combination of North Dallas Forty and Semi-Tough. In opening arguments, Gillett told the jury that Irvin’s eyes were bloodshot the night of the bust, which he believed suggested Irvin was either intoxicated or in a drug-induced stupor. Royce West, an African American state senator and one of Irvin’s defense attorneys, was outraged, rising to tell the jurors (only one of whom was black) that all African American men’s eyes are a little bloodshot. West played a unique race-celebrity card, saying the only reason the district attorney’s office had intervened in the case was because it saw a chance to put a superstar in his place—or what West called “the back of the bus.”

The truth was that prosecutors never would have thought twice about reinvestigating Angela Beck’s arrest if Irvin had not been in that hotel room. He was singled out, plain and simple. Yet it was difficult to find anyone who felt sorry for him: The man deserved everything coming to him. As the trial progressed, he looked more depressed, never smiling, his head hanging down. He brightened noticeably one morning when quarterback Troy Aikman arrived to sit in the front row of the spectator benches, telling the press he was there “to support a friend.” The Dallas Morning News editorial board was so offended by Aikman’s presence that it published a blistering editorial saying he could be sending a message to Dallas youngsters “that a reckless lifestyle is excusable.”

On what turned out to be the last day of testimony, Rachelle Smith took the stand outside the presence of the jury. (The judge wanted to hear what she was going to say to determine what parts of her testimony were suitable for the jury.) Her dark hair flowed down her back, her lips were frosted with a light-colored lipstick, and her curvy body was draped in a long white pantsuit, apparently borrowed from someone because the sleeves hung way below her hands. Although she had been photographed with braces on her teeth just a couple of weeks earlier, the braces were removed for her moment in the limelight.

Members of the media snickered when she insisted in a slightly indignant tone that she only went to the hotel rooms to have sex with Beck, never with Irvin. But suddenly, a pall fell over the courtroom as she described the way Irvin had her searched for listening devices. “He told me that if I didn’t change my testimony, he would put everybody against me and everybody would hate me. He said that he’d make a touchdown and everyone would love him again.” There was a long silence. Irvin dropped his head.

The next day that court was in session, prosecutors and Irvin’s lawyers agreed to a plea bargain. Irvin pleaded no contest to cocaine possession, a second-degree felony, in exchange for four years’ deferred probation, a $10,000 fine, about eight hundred hours of community service, and dismissal of the misdemeanor marijuana possession charges against him. In one respect, it was an unremarkable arrangement. Nearly everyone convicted of cocaine possession for the first time receives probation. On the other hand, Irvin escaped much greater problems. As part of the deal, Gillett agreed not to pursue felony witness-tampering charges against Irvin for his conduct with Rachelle Smith. Still, Gillett seemed satisfied. He was able to get Smith on the stand to tell her story in front of dozens of reporters from around the country. Irvin’s carefully developed public reputation was ruined forever.

Or was it? On July 17, the day the trial ended, Irvin showed up with his family at the Cowboys’ training facility to hold a press conference. Finally beside him was his wife, Sandi, who had never come to court. She sat expressionless, staring at their eight-month-old daughter while Irvin apologized to his family, his fans, his teammates, owner Jerry Jones, and even his dead father.

Then, at the end of the press conference—speaking without notes—Irvin dropped in a veiled suggestion that his era as a Cowboy was over. He said he was not reporting to training camp but was going to Miami to restore his relationship with his family. Of course, it didn’t make any sense for Irvin to go to training camp because the NFL was going to suspend him for five games anyway after his drug conviction. No matter. Irvin gave such a masterful performance, somber and sincere, that Dallas fans suddenly stopped discussing what he had done to Rachelle Smith. Instead, they began anxiously evaluating the Cowboys’ Super Bowl chances if Irvin didn’t return.

Afterward, Bayless shook his head and called Irvin “the consummate con artist.” But Irvin was right about one thing. He knew that all he had to do was come back to Dallas and make a touchdown and everyone would love him again.

- More About:

- Crime

- Jerry Jones

- Dallas