This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The Menil Collection, the privately funded museum that will showcase the De Menil family art trove, opens in Houston on June 7, and if the long-awaited event seems a bit anticlimactic, it is only because so many questions have already been answered about the building and its contents. The collection that will be exhibited in the long, low, gray clapboard structure down the street from the Rothko Chapel was revealed to the world in an exhibit at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1984 (see “Mrs. de Menil’s Eye,” TM, July 1984). Particularly rewarding in the areas of surrealist, primitive, and Byzantine art, the Menil Collection is spectacular in scope if rarely transcendent in quality.

Few reservations should greet the public debut of the building designed by Renzo Piano. It will display a few hundred choice pieces and provide study facilities and extensive storage for the rest of the roughly 10,000 objects acquired by Schlumberger heiress Dominique de Menil and her late husband, John, in four decades of collecting. A co-architect of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the most flamboyantly functional—and often dysfunctional—museum in the world, Piano has here created a superior yet more modest work. Piano’s building represents the fruition of De Menil minimalism, an in-house architectural style of monastic simplicity and geometric rigor softened by low-tech materials and natural light. The enforced restraint has clearly brought out the best in Piano. The sequence of sleek, white galleries, linked by a long, spinal promenade, is relieved by gardens that punctuate the modular precision of the floor plan like brilliant rectangles of primary color punctuate a Mondrian. Even the most characteristically Pianoesque high-tech flourish—rows of curved ferroconcrete “leaves” that function as all-in-one roof trusses, gallery ceilings, and giant-sized louvers to filter sunlight through the galleries—has the graceful lines of classical sculpture.

But whether this stunning set piece will become a vital force in the cultural life of Texas remains an unanswered question. Unlike most private museums, the Menil Collection is not intended as a mausoleum for its benefactors’ sensibilities but as a site for regularly rotating temporary exhibits as well as a resource for scholars (the upper story is a series of spacious and well-lit minigallery storerooms, where most of the collection will be kept).

At a time when publicly funded museums are increasingly cowed by financial pressures and by the tastes of the governing oligarchies, the Menil Collection, with its single, unusually liberal-minded despot, has an opportunity to provide an alternative to the much-processed culture that is often presented to museumgoers. And that the Menil Collection intends to offer a more zealous vision seems apparent by Dominique de Menil’s selection of Walter Hopps as its director.

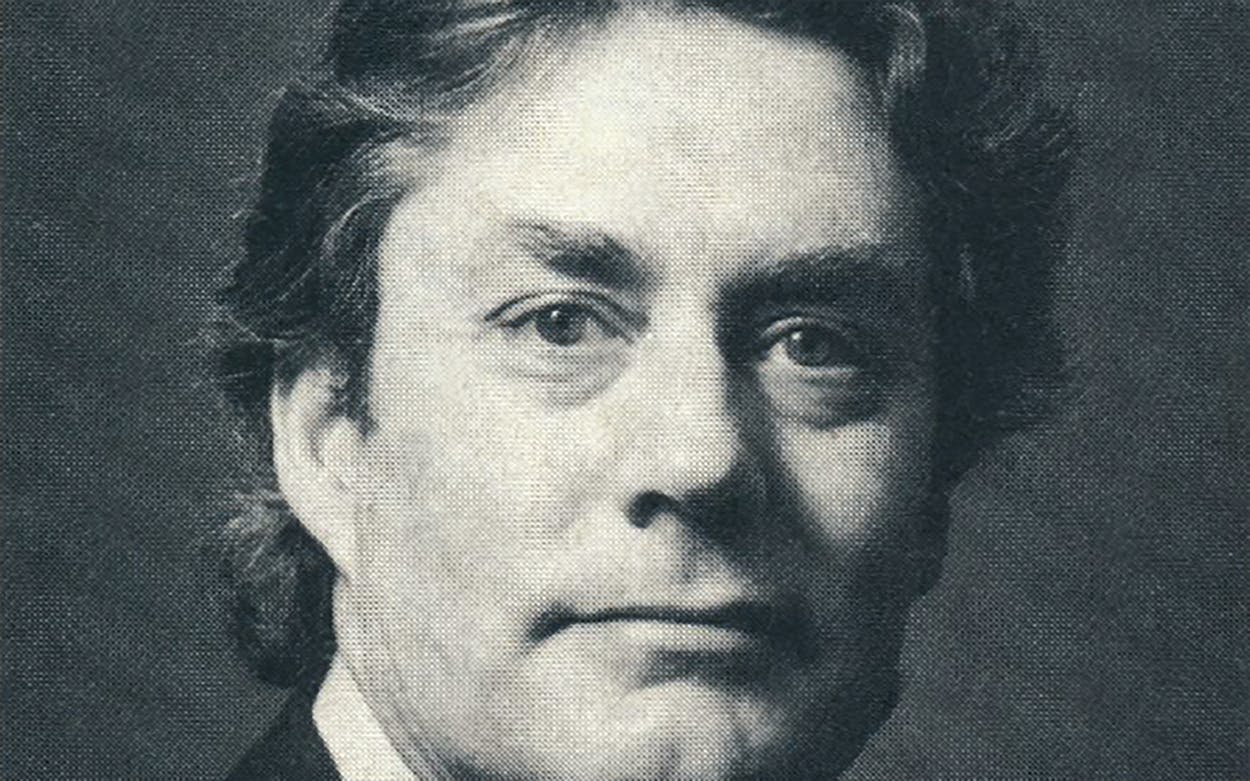

Hopps, one of the most colorful and controversial personalities in his profession, actually was named director of the Menil Collection in 1980. He has already assembled several shows under the De Menil aegis, including “The Rhyme and the Reason,” the dramatic unveiling of the De Menil family holdings. But until now, Hopps’s curatorial efforts have been easier to see in Paris than in Houston. The opening of the Menil Collection will provide a more accessible focus for Hopps’s wide-ranging—some would say rampaging—intellect.

Hopps’s career is the stuff of art world legends, but he is neither the flake his detractors perceive him to be nor quite the genius his more ardent supporters say he is. What he does offer is perhaps the museum business’s most inspired, intuitive sense of where to find the cutting edge in contemporary art. Although he is only a youthful-looking 55, Hopps has been, first as a dealer and then as a museum director, a major player throughout almost the entire span of post–World War II American art.

A fourth-generation Californian, Hopps was tutored as a teenager by noted collector Walter Arensberg. Arensberg introduced his protégé to Marcel Duchamp when Hopps was only seventeen, and the twentieth century’s foremost assailant of the traditional art object has remained a lasting influence on Hopps. In 1950 Hopps began an intermittent seven-year odyssey through Stanford University, UCLA, the University of Chicago, and Harvard University, an academic tour that netted him, he seems almost proud to say, not a single degree. But Hopps didn’t need academic credentials to sense that something extraordinary was happening to American art, and by the time he was 21 he had opened the first of several Los Angeles galleries that would give the initial West Coast exposure to many of the leading New York–based avant-gardists of the fifties, in addition to such seminal Westerners as Clyfford Still, Richard Diebenkorn, and Sam Francis.

During the fifties, innovative commercial galleries were the equivalent of today’s alternative spaces, and the scene that Hopps was instrumental in creating was one in which artists, beat poets, and progressive musicians freely cross-pollinated. The era was also a time when the dangers of being on the cutting edge were real. “A good many of my colleagues were dead before they were thirty,” says Hopps. “The wastage of people was terrible.” Poverty, drugs, McCarthy-era political repression, which seeped out of the movie industry to infect the California art community, accounted for the toll; Hopps’s Ferus Gallery, a collaboration with the notorious assemblagist Edward Kienholz, was named for an artist who shot himself when he was eighteen.

Hopps believes that the martyrdom of Jackson Pollock in the late summer of 1956 (the heavy-drinking artist died in the wreck of his convertible) began an era of acceptance for advanced American art. “By 1959,” he says, “the artists we represented knew that there was a chance for a career.” Hopps opened a branch of the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, formed a corporation, brought in a partner and an investor, and began to show another generation of New York radicals, like Frank Stella and Jasper Johns, along with such new-breed Californians as conceptualist Robert Irwin and ceramicist Kenneth Price.

In the late fifties and early sixties Hopps also became the guest curator at the Pasadena Museum of Modern Art in California, a small suburban institution that served as Los Angeles’ contemporary arts museum. Offered a full-time curatorial job in 1962, Hopps was to become the director by default when his predecessor abruptly resigned in 1963. During Hopps’s tenure as curator and director, he staged a remarkable series of exhibitions, ranging from historic modernism to the contemporary art of both coasts. Among the highlights were the first-ever retrospectives of Duchamp and Joseph Cornell and the celebrated “New Paintings of Common Objects,” the first museum survey of what would come to be known as pop art.

At the Pasadena art museum Hopps also became a central figure in one of the art world’s classic institutional dramas. Hopps’s plan for the future of the suddenly thriving museum was to acquire a quality collection, develop a professional staff, and merely add on to the existing building, an undistinguished Chinese-style mansion in downtown Pasadena; his board’s ambition was to throw most of the museum’s present and future financial resources into building a sprawling structure on a new site. Hopps protested that the cost of construction and maintenance for the new building would financially ruin the museum, but the board forged ahead. Plagued at the same time by the breakup of his first marriage, Hopps, in his own words, “just flipped out.” Returning to Los Angeles on the day scheduled for the formal unveiling of the model of the new museum, he found himself physically unable to leave the airport. He finally had the presence of mind to call a psychiatrist friend, who checked him into the mental ward at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The breakdown would end Hopps’s career at the Pasadena museum, which subsequently became a black hole for a series of unfortunate museum directors. Hopps was conclusively vindicated in 1974, when the museum went bankrupt and the costly building was taken over by collector Norton Simon, who replaced the contemporary art with collections of old masters and the French Impressionists. Despite the popularity of the Norton Simon Museum with the public, many critics suspect that Simon is merely renting a warehouse to display a collection that will end up elsewhere, and ultimately Pasadena will be left with an oversized building and almost no art to show in it, a fitting monument to the misplaced priorities of museum boards everywhere.

Hopps resurfaced in Washington, D.C., where during the late sixties he was a visiting fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, the country’s leading liberal think tank. He then went on to spend five years as the director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and seven years as the curator of twentieth-century American art at the National Museum of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution. The only surprising thing about Dominique de Menil’s recruitment of Hopps—he began working as a consultant to the Menil Foundation in 1979—is that it didn’t happen sooner; his instinct for innovation, his catholicity of taste, and his improvisational management style are also characteristic of most of the De Menil cultural enterprises. But so far, Hopps hasn’t been a loose cannon in the Houston art world. Although he has juried shows of emerging art and is a frequent visitor to the alternative spaces, he has also developed a respectful relationship with the two powers that be, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and the Contemporary Arts Museum. His most significant curatorial production, “The Rhyme and the Reason,” was a fairly disciplined attempt at a broad art-historical thesis, but the show effectively tiptoed around that history more effectively than it challenged it.

Hopps doesn’t plan any pyrotechnics for the opening of the Menil Collection. He says, “I’ve deliberately chosen not to present anything that was beyond the time and understanding of John de Menil.” The inaugural exhibits will consist of a collection of surrealist works; a memorial to Andy Warhol, whom Hopps showed in the early sixties; and perhaps the most arresting exhibit, a large group of John Chamberlain’s crushed auto-body sculptures, which will stand alone in a single six-thousand-square-foot gallery, giving full play to Chamberlain’s surprisingly lyrical color sense. As far as Texas art goes, Hopps’s short-term priorities are shows of such neglected modernist pioneers as Forrest Bess, the Bay City visionary and all-around eccentric who had a brief fling with an important New York gallery in the fifties, and the little-known Ben L. Culwell, a San Antonio native who studied at Columbia University in the mid-thirties, produced some magnificently horrifying expressionist scenes of World War II battle in the Pacific, and then gave up painting in the fifties and returned to his family business in Tyler.

While Hopps may be moving cautiously for the moment—at least by his own standards—he can hardly be presumed to have mellowed. “Each year I hope we have less attendance,” he says, a statement that would cost him his job anywhere else, “because the quality of the experience will be greater for those who do come.” That experience may indeed seem astringent to a public for whom a visit to the local museum has become the next best thing to a Sunday at the mall; the Menil Collection will have no shop, restaurant, education wing, or even director’s office in the main building (Hopps will continue to occupy his modest office in a gray clapboard house across the street). But Hopps makes it clear that he intends to challenge the state’s mainstream institutions without emulating them.

And when asked if he would ever consider directing a major public-run institution again, particularly since the kind of problems that buried the Pasadena Museum of Modern Art are endemic today, Hopps just answers quietly, “I don’t even imagine it.”

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Houston