Early one Monday morning, after a twelve-hour shift churning out mailing envelopes in a maquiladora—a U.S.-owned factory in Matamoros, Mexico—Carolina stands on tired legs in a line stretching toward the border with Texas. She makes it across the international bridge into downtown Brownsville in a half hour on most days. Occasionally it takes several hours, but even then it’s worth the hassle. She passes the time chatting with some of the other regulars.

In Spanish, a border officer asks the reason for her visit to the United States, and Carolina offers her usual response: “to donate plasma.” After that, it’s a short walk from the bridge to one of three collection centers. The morning’s first group of donors is finishing up as she arrives and settles into a reclining chair. A technician taps into a vein, and Carolina watches as a plasmapheresis machine slowly drains about a liter of her blood. It separates out the yellowish plasma, then returns the red and white blood cells and platelets to her body.

The process takes about an hour, during which she and roughly ninety other donors are required to sit in silence. “We’re all on our phones because we can’t talk to each other,” she said. “We have to stay awake, or they scold us.” She keeps her mind occupied by watching It’s Okay to Not Be Okay, one of her favorite Korean television series, on her phone.

To patients in need of costly plasma-derived therapies for diseases such as hemophilia or leukemia, or for trauma patients who count on plasma to treat their injuries, such donations can be invaluable. But to Carolina, her plasma is worth $50, and $55 more if she returns again in a few days, plus a $25 bonus for donating twice in a week. “I make more donating than I do at the maquila,” said the 42-year-old mother of two young girls, who asked that her surname be withheld from this story.

Carolina has been at it for roughly five years, one of thousands of Mexicans who cross into Texas weekly to sell their blood plasma—a bodily fluid containing proteins necessary to support blood clotting and the immune system—to one of a few dozen collection centers sprinkled along the border. The longest-operating of these facilities have been around at least fifteen years, and prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, they were among the highest-producing anywhere.

According to Grifols Plasma, one of the world’s largest collection companies, more than 600,000 liters flow from Mexican donors’ veins to its facilities in Texas each year, helping to fuel an industry that generated $33.2 billion last year and whose revenue is projected to reach $45.7 billion by 2027. When a change in U.S. Customs and Border Protection policy resulted in a temporary halt to Mexicans being able to donate, Spain-based Grifols and its Australia-based rival CSL said that this was reducing the amount of blood plasma they collect in the United States by 10 percent.

The relationship between these companies and their donors is symbiotic, yet strikingly imbalanced. Four multinationals, collectively valued at tens of billions of dollars, control about 80 percent of the worldwide market for plasma, which is used to develop treatments for a range of illnesses, including chronic respiratory diseases and neurological disorders. Fees paid to the donors vary depending on the location of the collection center, the available supply at the time, the donor’s weight (which determines how much plasma he or she can safely give), and the frequency of his or her donations. The average payment for a donation was $65 in 2020, the last year for which there is reliable data, though one industry analyst estimated the recent average at closer to $75. Meanwhile, a liter of plasma that costs as little as $150 to collect sells for as much as $500 after it is processed.

This business model relies on low-income donors in an area—the Rio Grande Valley—where many residents (on both sides of the border) are in poor health and don’t enjoy access to the sort of medical therapies their plasma makes possible. Researchers at the University of Michigan have found that plasma collection centers most often are located in or near impoverished neighborhoods.

Paying for plasma is illegal in Mexico, which is why Carolina and her compatriots travel to collection centers in Texas. The U.S. is one of the few countries in the world that permits the practice, which most others forbade after thousands of recipients contracted HIV and other illnesses from tainted blood in the eighties. “If you look at it from the perspective of organ donation, there are very strict rules against paying people, and you could make a case that plasma donation is donating an organ, or it’s something very akin to doing that,” said J. Wesley Boyd, a professor of psychiatry and medical ethics at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston. He donated plasma for money when he was a college student, but he now considers the practice exploitative.

A doctor provided by the maquiladora where Carolina works warned her that she is trading away her health for money and recommended that she donate less frequently. She once got so dizzy after donating that she took a tumble in the street. When she gets nauseated or vomits, she sips soda and nibbles on chocolate until it passes. Carolina worries that if she were to disclose these effects to the collection center, the staff might not let her donate. She views her earnings from plasma as a necessity. “There are moments that I’m a little afraid of getting sick from donating so much plasma,” she said. “But the money I make is for my daughters.”

The inequity of the arrangement isn’t lost on the thousands of plasma donors in Matamoros who exchange tips and frustrations in several Facebook groups. Carolina frequents the CSL Plasma Y Matamoros page, where donors often inquire about wait times at the international bridge and about which plasma center is paying the most—the one operated by Grifols or CSL’s two locations in downtown Brownsville. Contributors fret over bruising, scratches, and the dollar-to-peso exchange rate. “A question, have they let you donate with a burn,” one donor posted. Another comment by a recent donor, accompanied by a photo of the injury, read “this small bruise won’t go away.”

How much plasma someone can safely donate is determined by the donor’s weight, height, and sex. You must weigh at least 110 pounds, and the amount allowed ranges between 625 and 800 milliliters depending on those factors. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which regulates the country’s blood supply, sets a cap of 104 plasma donations per person each year (twice a week), suggesting that someone can donate at that level without severely impacting his or her health. Yet it’s notable that the U.S. limit is more than three times what is considered safe in many European countries, and even that lower number may be too much, according to Dr. Morten Haugen, who studies the effects of frequent plasma donation, at Innlandet Hospital Trust, in Lillehammer, Norway. “Donation frequency should allow for regeneration of the different plasma proteins between donations,” he said. “Based on the half-life of some of these proteins, thirty-three times per year is probably too often.”

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services warns that some donors will experience bleeding, bruising, dizziness, fatigue, or other pain. One study from the Red Cross in Europe found that donating too often can damage the quality of a person’s plasma, potentially lowering his or her ability to fight off infections. Plasma donation can even result in death, although this is extremely rare. Haugen told me there is a lack of good science on the long-term effects of habitual donation, adding that the current guidelines are based on scant research, much of which is industry funded.

The need for plasma-based therapies continues to grow, and if donors aren’t paid, producers might well struggle to source enough plasma. Indeed, it is little wonder that the U.S. supplies about two-thirds of the commercially sourced plasma in the world. “Demand is constantly evolving, especially as health care evolves, and there is greater awareness and understanding of rare and serious diseases,” a CSL spokesperson told Texas Monthly. “During COVID-19, we actually had to stop taking on new patients for our therapies because demand was outstripping supply.”

The amount of plasma collected nationwide fell by 20 percent in 2020 compared with the year before. At the same time, pandemic restrictions made entering the U.S. more difficult for the tens of thousands of Mexican nationals, including Carolina, who regularly cross the southern border on B-1 or B-2 visitor visas to shop, see family, or conduct business. Travel deemed nonessential was extremely limited. “We had to get an appointment in advance, but the plasma center was always changing the day or the hour,” Carolina said of the challenges during that period. “The border officials had a list, and if you weren’t on it, they sent you back to Mexico, and if we missed an appointment, we had to have someone set up another appointment for us because they didn’t allow us to cross and do it ourselves.”

In Brownsville the rate of uninsured

hovers around 34 percent, putting medicine, such as life-saving plasma for immunodeficiency and blood-coagulation disorders, frustratingly out of reach for many.

Making matters worse for Mexican donors, U.S. Customs and Border Protection decided in June 2021 that donations for cash were equivalent to labor for hire, a practice not allowed under a tourist visa. Grifols and CSL, each with a considerable footprint on the border, teamed up to sue CBP over the ban, claiming that it had likely cost them many millions of dollars. A federal district judge in Washington, D.C., granted a preliminary injunction last September, and Carolina, who had to resort to selling some of her daughters’ clothing and making party decorations to supplement her income, was able to return to donating plasma. It’s difficult to know how much longer she will have access to the collection centers because CBP won’t publicly discuss its plans for contesting the litigation. Even without this rule change, the border agency emphasized in a statement to Texas Monthly that it has other means of denying entry to plasma donors.

The industry has rebounded in the wake of COVID-19, in part by expanding its footprint across the U.S. More than two hundred new collection centers have opened since 2020, with some in nearly every state. CSL reported that plasma collection in the second half of 2022 was 10 percent greater than pre-pandemic levels, driving a 25 percent year-over-year increase in revenue for the $145 billion company. But most of the new facilities are far from the borderland. Matthew Hotchko, the president of the Marketing Research Bureau, which tracks the plasma business, expects it to continue to expand elsewhere. “The border centers could be a political football for a while,” he said. “That probably explains why the industry has made plans in areas they can count on.”

The Texas-Mexico border region, which is home to some of the poorest counties in the state, isn’t just economically disadvantaged; its health-care outcomes are also among the worst in the U.S. In Brownsville the rate of uninsured hovers around 34 percent, putting medicine, such as life-saving plasma for immunodeficiency and blood-coagulation disorders, frustratingly out of reach for many. Chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity affect Texas’s border communities at rates far greater than the state average. These conditions are mirrored on the Mexican side of the border. In Matamoros, 61 percent of those who died of COVID-19 complications also had hypertension, and 47 percent had diabetes. At the same time, the population survives on an average of less than $400 per person per month, with more than 70 percent living in poverty or considered at high risk of falling into poverty.

CSL Plasma, for its part, argues that the $6 million it spends each year on donor payments and employee salaries represents an investment in the communities in which it operates. The company sidestepped the question of whether it considers income levels when deciding where to place a plasma collection center, explaining that it selects locations, including its fifteen along the border in Texas and Arizona, based on population density, the availability of real estate, and zoning laws, according to a statement to Texas Monthly. Grifols, which has more than fifty collection centers across Texas, including the one in downtown Brownsville, directed questions to the Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association, an industry trade group. “Every donation directly contributes to helping nearly 125,000 Americans with serious and often life-threatening conditions live healthy and normal lives, as well as countless others facing trauma and emergency medical needs every day,” a PPTA statement said.

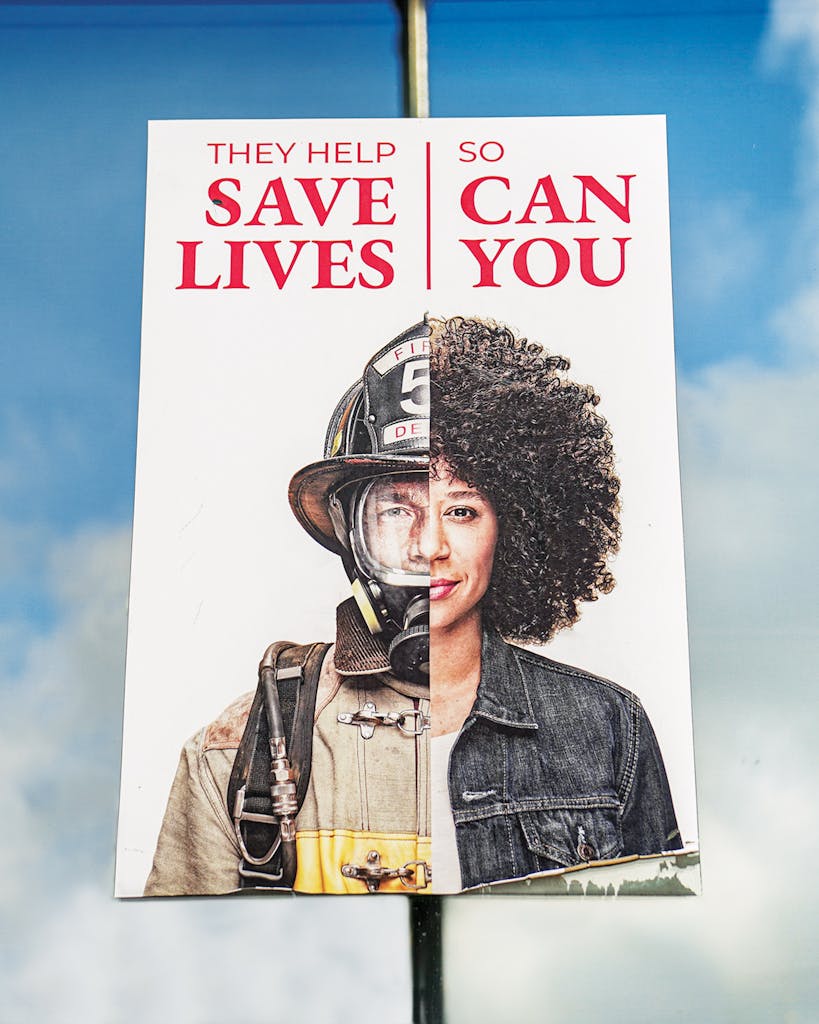

Downtown Brownsville ticks all the boxes for where plasma companies typically set up shop, including the predictably attendant poverty. CSL has the most prominent location among the collection centers, less than two hundred yards from the international bridge, next to a church and a duty-free shop and across the street from Texas Southmost College. Some signs in English on the front of the CSL collection center tout blood plasma donation as a way for ordinary people to save lives, while the only Spanish-language sign calls it “the best way to make money easy.” Every weekday from 5 a.m. until 8 p.m. (with slightly reduced hours on weekends) donors file inside. Afterward, most of them head for a pair of nearby ATMs, using a reloadable debit card provided to them by the plasma center to get their cash, paying a $3 withdrawal fee, before spending another $1 to cross the bridge back to Matamoros.

One afternoon in early March, I could easily spot plasma donors by the blue or brown bandages worn around their elbows. Among them, I struck up conversations with carpenters, electricians, stay-at-home parents, factory employees, and truck drivers. A health-care worker told me he was selling plasma to afford medication for his daughter, who was born prematurely. A convenience store clerk was donating to build a room onto her house for her aging parents. Another donor was there for money to buy meat and beer for his weekend barbecue.

Alejandra Villalobos, an eighteen-year-old graphic design student who moved in with her grandmother to ease the financial burden on her mother, sells her blood plasma twice a week to help support her four younger sisters. “We live on my grandfather’s pension,” she explained, but the money stretches only so far. “My grandmother covers my tuition, most of it anyway, but not books, supplies, and bus fare. That’s why I’m donating.”

I also met Mario Guzmán, as he was leaving CSL on his way back to Matamoros. The 45-year-old, who makes roughly as much selling plasma twice a week as he does at his full-time job in a tortilla factory, scoffed at the notion that he is considered a donor. “The way I see it, it’s like the maquila,” Guzmán said. “It exploits too many people like us.” Carolina takes a slightly different view. “You can look at it however you want, but in reality it is still donating,” she said. “Because they don’t pay what plasma is really worth.”

She usually makes it back home to her girls, ages eleven and thirteen, by mid-morning. She gets them ready for school, which they attend in the afternoon—an option offered to parents, such as Carolina, who work the night shift. She squeezes in a few hours of sleep before going back to work in the maquiladora in the evening. She squirrels away what she can for when the girls are sick and need medication, or for their school supplies, and even then it is not always enough. She is well aware that her plasma helps others, “but honestly—the money,” she said. “I can’t describe how much it means to me.”

Aaron Nelsen is a freelance journalist based in the Rio Grande Valley.

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Bloody Business at the Border.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Health

- Business

- Mexico

- Medicine

- Brownsville