As Austin is to Texas, so Montrose has long been to Houston: a liberal, weird oasis in a sea of red, a refuge for musicians, artists, bohemians of every stripe, and the nexus of the city’s LGBT community. Indeed, when Austin was still a relatively straitlaced Southern college town, Montrose had already unfurled its freak flag. Founding Texas Monthly editor William Broyles claims Montrose, and not Austin, as the true birthplace of Texas counterculture.

And just as in Austin, Montrose old-timers love to let you know that you are a few years too late for the real party. Hippies, punks, and LGBT folks alike will all tell you, a wistful look in their eyes, “You should have been here when …” Followed, of course, by the declaration that Montrose is dead.

Over the last forty or so years, the roughly seven square miles southwest of downtown Houston (bounded by South Shepherd on the west, Bagby on the east, West Gray on the north, and the Southwest Freeway to the south) has been declared dead more often than Blues Clues host Steve Burns.

Pretty much everyone agrees that Houston needs Montrose. Way back in 1973, the late Montrose architect and professor John Zemanek called Montrose “essential to the city of Houston”:

It provides a humanistic element at its core, like the Left Bank in Paris. If the Montrose as it is now was wiped out by high rises and commercialization, the city would become sterile and materialistic to the point where culturally stimulating people would move out, and everyone would lose in the long run.

I was conceived in Montrose by hippie parents, in a house on the corner of Dunlavy and West Alabama, during the crazy run-up to the moon landing. I spent much of my youth and adulthood just across the Southwest Freeway, in what is now known as the Museum District.

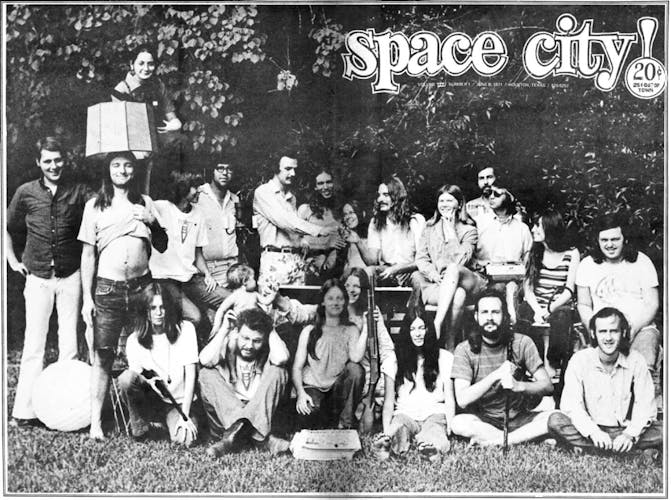

Before they moved to Nashville in 1974, both of my parents were deeply involved with the Montrose underground, at Pacifica radio station KPFT and the hippie newspaper Space City! They ran with the wild folk music crowd of that era: Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, Rodney Crowell, and Richard Dobson among them.

My late uncle ran a small publishing house called Wings Press out of his home on Yupon Street in the heart of Montrose for the last five or so years of his life in the eighties, publishing poetry and experimental fiction, much of it by local writers.

I spent most of the 2000s as music editor of the Houston Press, and my duties frequently took me to Montrose, to venues like Rudyard’s, 1980s revival house Numbers, and Avant Garden, a freewheeling, Old World–style coffeehouse where you were as likely to hear erotic poetry or gypsy jazz as backpacker hip-hop. Or maybe I’d find myself at venerable Texas folk mother church Anderson Fair, an incubator for the careers of legends like Van Zandt, Clark, Lucinda Williams, Nanci Griffith, Robert Earl Keen, and Lyle Lovett.

And then there was Earthwire.net, an internet radio station that grew out of the old Montrose pirate radio movement and was based in a long-since-demolished garage-like structure, where blues greats like Little Joe Washington mingled with punks, noise artists with Rastas, rock-en-Español madmen with neo-honky-tonkers, all fueled by an endless supply of Busch tall boys and fragrant fumes.

“You certainly aren’t going to find that old Montrose spirit in Montrose anymore,” Earthwire proprietor M. Martin told me in 2003, on the occasion of its closing. “My old ’hood has been gentrified beyond the point which I feel welcome in it anymore.”

I’ve heard generations of these death-by-gentrification declarations. Hippies might tell you it died around the time Space City! went under in 1972. There have almost always been laments about rising rents: In 1973, Montrose was featured in Texas Monthly’s third-ever issue, with folk singer Don Sanders fretting about a mass exodus of creative types brought on when area leases topped a whopping $100. (“Montrose Lives!” was that article’s defiant headline, suggesting that, even then, some were declaring the neighborhood something other than alive.) Punks might tell you it died when their underground paper, Public News, went under in 1998. There was Earthwire’s 2003 demise. The fizzling out of the Westheimer Street Festival in the mid-2000s spelled doom for others, while many in the LGBT community might tell you Montrose died when the Pride Parade moved downtown two years ago. A consistent through-line has been the steady rise of rents: once quite affordable, the Montrose zip code of 77006 is now the sixth most expensive in Texas.

If the neighborhood has a forum, it is KPFT, the free speech, listener-supported radio station located on Lovett Boulevard, in the heart of the neighborhood. While the station has lurched from crisis to crisis over its entire 47-year existence, some believe that it might now finally be in a death spiral—its audience aging, its pledges dwindling, the music audience now slaked by Spotify, and its revolutionary politicos now meeting in Facebook groups. As goes KPFT, some contend, so goes Montrose.

Latter-day Montrose has its defenders. One such is Omar Afra, founder of Free Press Houston, the underground paper currently most representative of whatever Montrose is now, and whose non-Montrose-based Free Press Summer Fest is more or less the successor to the old Westheimer Street Festival.

“Montrose is yesterday, today, tomorrow,” Afra claimed in a recent Facebook debate. “John Nova Lomax, you have beat to death this whole ‘Montrose has changed’ cry for a decade now? In the amount of years you have been lamenting, the neighborhood has gone through ten different iterations of itself. It is constantly changing. When you were younger and hanging in this neighborhood, it was full of people lamenting how it used to be. Forever and ever and ever, people will constantly say how THEIR good ole’ days are better than the current youths. Let them have it. You had yours.”

• • •

Afra has an ally in Ada Calhoun, author of St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street. Calhoun was born and raised in that now-gentrified East Village epicenter of cool. She stopped by Houston’s Brazos Bookstore a few years ago on her book tour and reminisced about her childhood there, one where crack vials, hypodermic needles, and prostitutes were common sights on her daily rounds, just as they once were in Montrose.

Over the centuries, St. Marks Place—all three blocks of it—has served variously as Dutch settler Peter Stuyvesant’s pear orchard, a ritzy residential district, a mob stronghold, and the backdrop for Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti album cover. Leon Trotsky helped foment the Russian Revolution while living there back when it was a hotbed of radical Eastern European immigrants. Generations later, it played host to Andy Warhol, the New York Dolls, the Velvet Underground, the Ramones, and the Beastie Boys.

Calhoun contends that at some point, pretty much every participant in every one of these waves concluded that “their” St. Marks Place was dead, over, kaput, finito. “You should have been here when … (Lou Reed was shooting smack in the alley … Thelonious Monk was banging the keys in that basement club … Ad-Rock was skating down the street, ballcap askew, with a 40 in his hand …)”

And yet, Calhoun believes, cool St. Marks lives on. Yes, it has lost some of its more colorful businesses, and the rent is sky-high. “But teenagers still come from all over to get drunk there right now,” Calhoun said. “The sidewalks are still free and always will be.”

Her conclusion? “People want to remember the place as it was when they themselves were the hottest they ever were or will be, when they were nineteen, twenty, twenty-one years old. They want to remember it in that image.”

It’s not the neighborhood that’s dead and gone; it’s our own sexy young selves. And maybe that is the root of all nostalgia—we don’t miss what used to be, we miss who we used to be.

Could it really be that simple? I can think of at least a dozen neighborhoods that over time have simply ceased to be what they once were. On the edge of my childhood memory I can recall visiting Van Zandt and “Uncle” Seymour Washington in Austin’s Clarksville district, once an African American enclave with a smattering of hippies, now a red-hot yuppie area where the average home costs just under a million dollars. In Houston, I’ve seen similar transformations in places like Fourth Ward / Freedmen’s Town, Riverside, and West University Place, the last of which was a solidly middle-class neighborhood in my father’s youth; today, it’s the wealthiest zip code in the state. The character of those places objectively changed. It had nothing to do with the wrinkles and paunches of their long-gone denizens.

I asked Calhoun if she agreed that such complete transformations were possible. “Of course,” she said. “Look at SoHo in New York. Hypergentrification exists. A neighborhood can only take so many towers and Walgreens before it ceases to be what it used to be.”

Which brings us back to Montrose—has it gentrified or hypergentrified? Is it just old and cranky me succumbing to get-off-my-lawn-ism, or does it retain its old “magic,” a word that comes up again and again in former Montrosians’ memories of the place?

Calhoun’s talk was hosted by local historian James Glassman, who edits the Houstorian blog and recently published The Houstorian Dictionary. Glassman is sanguine about the Montrose of today. As long as it still holds “anchor tenants” like the University of St. Thomas, the Menil Collection complex, and the Greek Festival, Glassman believes it will remain attractive to “artistic troublemakers” like Van Zandt and “misfit tinkerers” like native son Howard Hughes.

So, Montrose is dead; long live Montrose? I am not so sure.

This much is true: the latest oil boom, which lasted from 2009 to 2014, was not kind to many lovers of old Montrose, nor residents of same. Many have been priced out. Others, like Earthwire empresario Martin, left by choice; after calling Montrose home since Sid Vicious was alive, he decamped to Portland a few years back.

“For myself and many others, Montrose was a refuge in my youth from the stultifying, insipid blandness of suburban Houston and the dangerous imbecility of Texas at large,” Martin told me. “But the musicians, artists, and bohemians whose contributions made it what it was have mostly been priced out. The public spaces where they formerly gathered have been turned into fashionably dive-y hangouts for the corporate professionals who can afford to live there.”

Just as they have everywhere else, corporatization and the digital revolution are altering Montrose’s retail landscape. While the district’s upscale bar and restaurant scene is booming, Montrose has lost many of its other “third places”: bookshops, video and record stores, and music venues. Today, only four record shops remain in the entire district, while as late as 2002 there were five on or near a half-mile stretch of South Shepherd alone. Two have closed, a third has moved to the city of Bellaire, and Cactus, the city’s most famous record store, has decamped just beyond the fringe of Montrose. Though a handful of venues remain—notably Rudyard’s, Anderson Fair, and Avant Garden—Montrose is no longer the vital epicenter of Houston’s live music scene. Newcomers to the neighborhood brought with them a rash of noise complaints. “The civic associations in Montrose want it to be like [suburban] Cinco Ranch,” said David Crossley, president of Houston think tank Houston Tomorrow. High rents have priced other small venues deep into the East End.

Weirdly, into that retail breach has stormed an invasion of mattress stores—today, there are no fewer than three purveyors of sleep sets on that same short stretch of South Shepherd pavement that was once Houston’s record store row, inspiring Glassman, the local historian, to jokingly rename the area “the Mattrose.” Where once South Shepherd was a place to buy music to pep you up, it is now a street intent on putting you to sleep.

Gentility has encroached on Montrose from the snooty, River Oaks–lite Upper Kirby district to the west, while Midtown’s party-hearty bros have invaded from the east and north. Property taxes and rents have both skyrocketed; despite the oil downturn, it’s almost impossible to find a one-bedroom for less than $800 a month. Having gained more acceptance from society at large, the LGBT community has scattered to neighborhoods like Westbury and Oak Forest. Bohemians have fled to the East End, Acres Homes, and Independence Heights—the gentrified Houston Heights no longer an option—or have left Houston altogether.

In my view, Old Montrose has perished not from a single death blow, but rather by a thousand cuts, most coming in the last few years. Mary’s, long the city’s most iconic gay bar, gave way to a high-end coffeehouse. Chances, Montrose’s only full-time lesbian bar, morphed into Underbelly, the city’s “it” restaurant of the most recent oil boom. The last bastion of Felix, the old-school, family-friendly Tex-Mex chain, closed down and was reborn as an outpost of Austin’s chic Uchi sushi empire. Ruchi’s Taqueria (a musician-friendly home of way-late-night beers served in red iced tea tumblers) and quirky-bordering-on-insane jewelry boutique Fly High Little Bunny were razed to make way for a CVS. La Jalisciense, another late-night taqueria beloved of musicians, was replaced by a more upscale Mexican restaurant. A Raising Cane’s outlet landed like a spaceship from suburbia smack-dab on Westheimer, and Texas Junk Company, for years a staple on lists of “quirky things to do while in Houston,” closed down, its owner decamping for Moulton, Texas.

Meanwhile, all over the area, lawns and antique bungalows have given way to tall, lot-filling Texas Tuscan condos and McMansions. Seventies-era garden-style apartment complexes have been replaced by luxury mixed-use mid-rises.

In one of the more definitively Houstonian real estate happenings I’ve seen in 47 years of observation, H-E-B bought and razed a lovely (if crumbling) live oak–shaded apartment complex from the forties directly across the street from a Fiesta supermarket, one beloved by Montrose’s artsy set for its cheap and lovingly selected wine selection, international foods and produce, great seafood counter, and simply amazing in-store music playlists. (You’d hear everything from Bo Diddley to relatively obscure Beatles tunes like “Hey Bulldog” to Otis Redding to Poco in its aisles.) Faced with the shiny new store across the street, Fiesta closed down and was soon replaced by … a luxury mid-rise apartment complex. So, if you are keeping score at home, Houston tore down a historic apartment complex to build a grocery store across the street from where we tore down a grocery store to build a brand-new apartment building.

Welcome to Houston. Welcome to Neo-Montrose.

• • •

In 1980, seven years after Don Sanders decried Montrose’s triple-digit rents, Dick Reavis wrote in the now long-defunct Houston City magazine that Montrose was again at a tipping point:

The neighborhood…was the kind of place where young friends could drop in on each other unannounced and share meals, ideas, drugs, even sex.

As the Seventies meandered toward the Eighties, Montrose changed. Some of the youth culture crowd bought real estate and turned wrecks that had housed hippie communes into $100,000 and $200,000 redos. Rents went up. Many erstwhile Montrose street people moved away to take mundane jobs in East Texas towns such as Tyler, Jacksonville and Palestine. Of the hard core that remained in Houston, many left Montrose for cheaper digs in neighborhoods such as the Binz or the Heights, while others retreated to the few slumlike niches within Montrose. As had happened in New York’s Greenwich Village a generation earlier, gays and the youth culture began to set the tone for Montrose, culturally and politically. Neighborhood balladeers moved to the suburbs of Bellaire and Meyerland. Drug dealers became hip capitalists and opened restaurants and clubs. A co-founder of Space City!, a Montrose-based underground newspaper of the Sixties, became a public relations man. Some of those who had experienced the rush time the Sixties imparted—the exhilaration of moving faster than events, of seeming to change the world—tried to recapture the sensation through drugs or drinking binges or living dangerously outside the law. But it was never the same. The younger crowd paid its ritual visits to Montrose clubs and scenes, but they didn’t know the old faces that tried to blend in as the avant-garde ambience drifted from rock to new-wave and punk.

Digs are no longer much cheaper in the Binz (now rebranded as the Museum District or Midtown, depending where you are) or the Heights. Neighborhood balladeers are thin on the ground today, and certainly can’t afford Bellaire or Meyerland. Reavis’s slum-like niches are now mere crevices, and finding people who hope to change the world is a fool’s errand there today. The ambience has shifted again, this time away from music to food and drink: hot chefs and mixologists like Underbelly’s Chris Shepherd, Hugo Ortega of Hugo’s, and Bobby Heugel of Anvil are the neighborhood’s new rock stars, feted online and in the papers, their patrons wealthy young bankers and O&G execs.

Speaking of oil: Reavis wrote his requiem on the cusp of Houston’s last great oil bust, one that, along with the simultaneous AIDS epidemic, brought Montrose’s real estate prices crashing back to earth. Thanks to oil and the panic over AIDS, Montrose remained a bastion of the young, the broke, and the brave for another two decades. As the current oil glut drags on, that scenario could be in store again, but wishing a return to bust-era Houston just to save Montrose is selfish at best and downright cruel at worst.

For the time being, enough of its spirit remains intact for it to remain Houston’s, and Texas’s, coolest neighborhood. You can still sweat over a beer or three at a shaded picnic table at the West Alabama Icehouse, enjoy a picnic lunch under the live oaks at Menil Park, meditate in the somber Rothko Chapel, or dive deep into rock and roll darkness at Lola’s.

Sure, it’s getting harder and harder to find lunch for under $15, a cocktail for under $10, or a place to lay your head for under a grand a month. But just as on St. Marks Place, Montrose’s (cracked and buckled) sidewalks will always be free.