Driving into the tiny West Texas town of Sanderson feels a bit like finding a pile of bones in the desert—intriguing, but you might at first be reluctant to look more closely. An hour’s drive southeast of Fort Stockton, this far-flung community of about eight hundred residents is a little rough around the edges, but if you take the time to get to know it, you’ll be glad you did.

As I arrived, I passed decrepit buildings, a crumbling old theater, and a Stripes gas station that sells tacos and burritos made on-site. The Z Bar Trading Co. hardware store, where a twenty-foot metal sculpture of a T. rex welcomes visitors out front, drew my eye. My gut told me just to gas up and move on from Sanderson—which is what I probably would have done, except I’d heard the place mentioned enough times in my travels around the state that I had already booked a room.

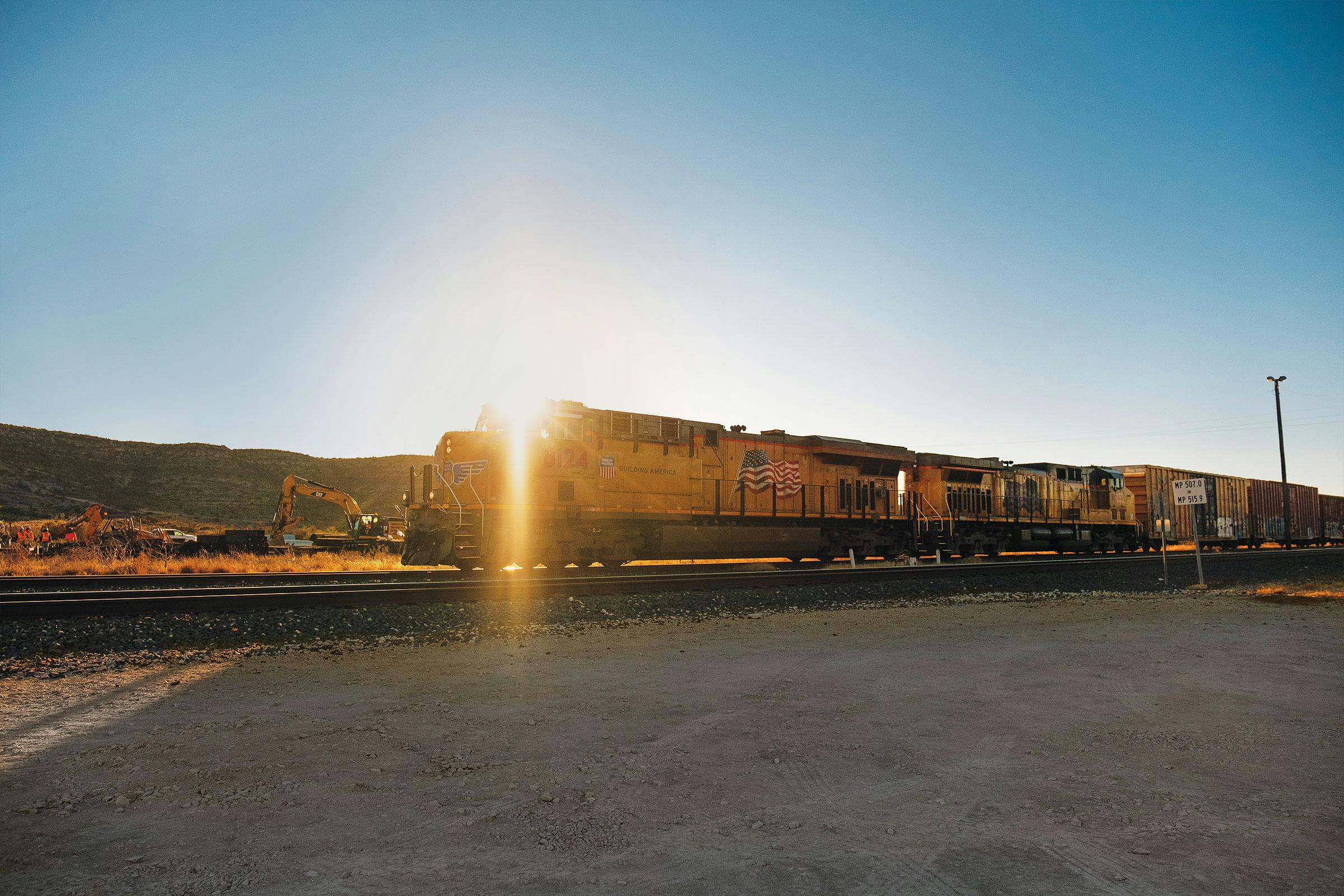

Founded in 1882, Sanderson is the Terrell County seat and was once a thriving ranching community. The construction of the Southern Pacific Railroad put it on the map in the 1880s; today, the Amtrak train still stops in Sanderson on its route from San Antonio to El Paso. Sheep and goat ranching here had produced a vibrant mohair and wool business by the 1930s, and oil and gas gave the town a brief boost after that. But the population peaked around three thousand in the fifties and has been dropping ever since, as a result of both the decline of the ranching and railroad industries and the construction of Interstate 10 about an hour away, which allows motorists to bypass the town entirely. Today, the school district, law enforcement, the railroad, and a small but growing tourist industry provide the few jobs in the area.

Still, Sanderson has charms that make it well worth a detour. From one hillside in the summer, you can watch Mexican free-tailed bats emerge from beneath a railroad bridge below. You can hike a trail that winds through the foothills surrounding the high school football stadium; the arena, locals tell me, fills with water after an unusually heavy rain, creating a popular spot to splash around. At the Ranch House restaurant, waitresses proudly pack pistols on their hips while slinging classic plates of pork chops and chicken-fried steak.

Sanderson gets a nod in the movie No Country for Old Men; protagonist Llewelyn Moss lives on the town’s outskirts, in a desolate trailer park called the Desert Aire. (Those scenes were actually shot in New Mexico.) In the real Sanderson, the place to stay is the much more stylish Desert Air Motel, built in 1960. After a complete renovation, it now has a look straight out of Palm Springs: a vintage red-and-white sign casts light on an L-shaped plan of sixteen rooms.

Sara and Nick Ryza, who split their time between Sanderson and Dripping Springs, bought the motel with their partner Joe Godin two and a half years ago, after spotting its For Sale sign on the way home from a camping trip to Big Bend National Park. The motel was still in operation, but in need of a face-lift. They renovated the rooms, preserving the original pink bathroom tile and installing a “cowboy tub,” made from a metal horse trough, outside one suite. Today the clientele includes folks traveling to Big Bend, plus a steady stream of hunters and work crews. “It’s not a destination,” Sara said.

Not yet, anyway. Some say if you put your ear to the ground, you might hear the faint sound of something coming down the tracks. A visitor center in town provides tourist information about the national park, just over ninety miles to the southwest. A new train platform was under construction during my visit. And for one day each April, U.S. 285 between Sanderson and Fort Stockton closes for the Big Bend Open Road Race, where amateur race car drivers pilot Corvettes, Mini Coopers, and everything in between against a backdrop of cactus- and scrub-covered hills. And in nonpandemic years, the city’s Fourth of July celebration draws revelers from across West Texas, with street dances in front of the courthouse, a Sanderson High School reunion, and a watermelon-eating contest.

Prickly Pride

Sanderson is the Cactus Capital of Texas. Because the town sits at the convergence of three ecological zones, it’s home to dozens of succulent species, from the kingcup to the Spanish dagger.

You can’t talk about Sanderson, though, without mentioning the flood of 1965. When Jim Davis, who spent 42 years working for the railroad, and whose father was killed in an on-the-job train accident, swung by the motel to pick me up for an off-road-vehicle tour of town, our first stop was a small park downtown, which has a memorial to those who died in the disaster. Davis was nine when it happened. On June 11, heavy rain west of town created a raging river that poured into dry canyons, breached a diversion dike, and broke bridges on its way into Sanderson. Twenty-six people, mostly residents in low-lying areas and a family staying at a small hotel, were swept away.

As we paused in front of a plaque listing the victims’ names, Davis shared his memories of the tragedy. “We turned down the street and looked [at the water],” he said. “We could see the water rolling and railroad ties twisting like paper clips.” Two of the bodies were never found.

For weeks after the deluge, Davis said, he and his classmates had to line up for typhoid shots because of fears the town’s water supply could be contaminated. And when all that floodwater washed through, it carried great clumps of mohair from a warehouse at the edge of town. The wet fiber stuck to everything, turning into a sort of cement. Years later, Davis said, his brother found wads of it beneath a home he was working on. The smell instantly brought back memories of the disaster. To protect the town, the Natural Resources Conservation Service constructed eleven retention dams, the last of which was completed in the eighties.

My tour continued as we puttered past the old theater I’d noticed as I arrived in town, the Princess; inside, broken glass and wooden beams were strewn on the floor. It concluded at a former quarry nicknamed the Rock Crusher, where crews once harvested gravel used to build and maintain railroad beds. I needed food by then, so I headed to the Ranch House, which advertises its “packin’ waitresses” on its Facebook page. “It’s loaded and there’s a bullet in the chamber,” waitress Jessica Martinez told me before turning away to chat with two railroad workers, who were celebrating the retirement of one of the men after 25 years on the job. I took my burger to go.

My next stop was the old Kerr Mercantile building, where residents once bought beefsteaks, filled their gas tanks, and inspected model homes in the yard out back. “It was a microcosm of what everybody needs,” a local told me. Inside, I met Travis and Katie Roberts, who in 2012 converted the market into the Z Bar Trading Co., a True Value hardware store that also sells home goods, trinkets, pottery, and a massive herd of animal-shaped yard sculptures imported from Mexico.

The Robertses moved here eighteen years ago from Lancaster, outside of Dallas, to raise their children and find a slower pace of life. They now measure distances in hours instead of miles and are used to spending half a day visiting the H-E-B in Del Rio. “Produce is west, meat is north, everything else you go east,” Travis said.

I also wandered into a funky attraction called Oddities and Odyssey, where owner Ken Case, 73, showed me his collection of fossils and artifacts and introduced me to Victor, his 130-pound, 70-plus-year-old sulcata tortoise, who lives in a spacious stone-lined pen in the front yard and comes when called.

Most folks here seem happy to keep Sanderson just as it is, quirks and all, but some residents say it could be the next big thing in the region. Liz Rogers, who lives in nearby Alpine and owns a two-bedroom house in Sanderson, sees the town as an up-and-coming alternative to trendier West Texas enclaves such as Marfa and Marathon. “I wanted to be smart and think of some little town where I could start buying property,” she told me. “The whole town is like a movie set from the fifties.”

Rogers connected me with Pam and Mark Walker, who bought their first of four properties here sixteen years ago, after passing through Sanderson regularly on their way from Lakeway to Big Bend. They fell for the stark landscape, adobe buildings, and dry climate. Here they could own their own slice of the Chihuahuan Desert. “Marfa has passed us by, but Sanderson looked like a huge opportunity to get something in our budget,” Pam said. “It was a fresh palette to work with.”

That night, as I soaked in the horse trough on the private patio outside my motel room, I sloshed the water between my toes. The sound of music drifted my way; Jim Davis had arranged for his rock and country band, the Terrell County Buzzards, to hold practice in the motel courtyard. A warm breeze ruffled my hair, and a train rumbled in the distance. Looking up at the stars popping out in the sky, I realized just how much I liked the gritty, sunbaked sincerity of Sanderson.

Pam Leblanc is an Austin-based journalist who specializes in outdoor adventure and recreation.

This article originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Desert Dreaming.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Hotels

- West Texas