It’s true nationally, and it’s true at the University of Texas at Austin. Even when students from low-income families make it to college, the financial, academic, and social challenges they face mean they are less likely than their peers to graduate on time.

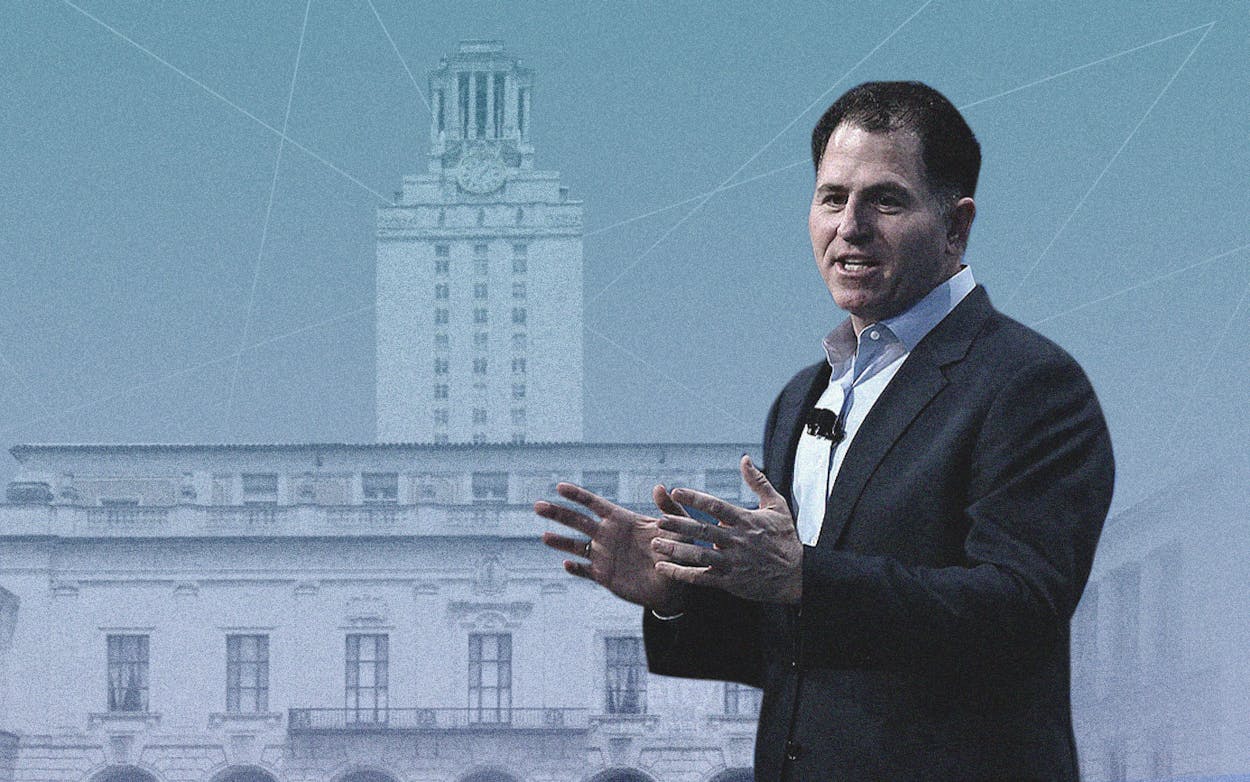

At the state’s largest public university, only 73 percent of students from low-income families graduate within six years, compared with 86 percent of their classmates overall. This fall, UT-Austin will debut a new $100 million, 10-year partnership with the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation to help more of these students earn degrees, with a goal of raising their six-year graduation rate to 90 percent.

The new partnership provides money in the form of $20,000 grants to help the most financially needy students defray the expenses of tuition, housing, transportation, and textbooks. The program also promises to change the way the university supports students from low-income families by funding a team of on-campus staff dedicated to help guide students through academic or personal issues that might affect their ability to earn a degree. All students from low-income families—determined by their eligibility for federal Pell grants, a commonly used measure of financial need in higher education—will get those services, while only the neediest will receive the grants.

“When you talk about what do these students need on their journey to graduate—they obviously need financially support. That is very, very important,” said Janet Mountain, executive director of the Dell Foundation. “But we know that money alone does not deliver the graduation rates that we need, and that’s because these students need more than a check. Even when their costs are covered, these students still are not making it through to graduation at the same rate as their peers.”

University officials estimate that the program will serve about two thousand students per class, or about 20 percent of the undergraduate population.

Graduation rates are especially useful for measuring the success of financially needy students, who can be caught between carving out time for their studies and figuring out how to pay for school. Prolonged worry about how to pay for meals, textbooks, and housing takes its toll in the classroom. Even little things—like not being able to afford supplies for a particular course—can keep students from graduating on time. Taking longer to graduate also means students must spend more money on tuition. And if students drop out, they are then saddled with student loan debts without the added earning power of a degree.

Americans now owe more than $1.5 trillion in student loans, more than twice what they owed a decade ago, surpassing all other forms of debt except mortgages. Almost 50 percent of young adults under age thirty with a bachelor’s degree have outstanding student loans. How to help these approximately 43 million borrowers has become a major topic on the presidential campaign trail, with some candidates proposing cancelling the debt altogether. At UT–Austin, about 40 percent of students go into debt to pay for their education, at an average of about $35,000, according to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Of course, the price of higher education also keeps many financially needy students from even enrolling in the first place. At UT–Austin, the current total costs of attendance for an in-state student average about $28,000, including about $11,000 in tuition. Though it’s difficult to get data on the family income of students at UT, the university closely tracks the number of Pell grant recipients, a rough proxy for the percentage of students who come from poor and working-class families. The vast majority of Pell recipients come from families who earn less than $50,000 a year. At UT–Austin, the percentage of students receiving Pell grants has gradually dropped since 2011, from a high of 28 percent to 23 percent in the 2017–2018 school year. A university spokesperson said the year to year variations in Pell recipients mirrored the demographic and economic trends in the state, noting that the state’s poverty rate also peaked in 2011.

The Dell partnership is the latest in a series of UT–Austin initiatives aimed at improving academic outcomes for students from low-income families. Since 2018, the university has offered free tuition to students whose families earn less than $30,000 a year. Last summer, university officials announced they would broaden that policy to students whose families earn less than $65,000 a year. About a quarter of the university’s in-state undergraduates in the upcoming academic year—roughly 8,600 students—will have their tuition paid for under the new policy. With the expanded financial aid program, the university joined the ranks of dozens of other Texas colleges, including Texas A&M and Texas Tech, that have enacted similar policies over the past several years.

It is all part of a “very concerted effort” to close the graduation gap between economically disadvantaged students and their peers, UT President Greg Fenves said.

“We would like to have every student who is admitted to UT and comes here graduate,” Fenves said, noting that some students leave for reasons unrelated to their financial backgrounds. “What we get concerned about is when students don’t graduate here because they aren’t sure how to succeed in college because no family member has been to college … We don’t want a student to drop out because there is a family emergency and they need $400 that they don’t have.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Higher Education

- Michael Dell

- Austin