This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Like so many former battlegrounds, Vidor’s public housing project was once pleasant and innocuous. As such places go, it has little in common with the cramped high-rise dungeons that have become the pathetic cliches of America’s failed efforts to provide shelter for those in need. Built forty or so years ago and refurbished in the past decade, it consists of 74 small brick duplexes shaded by a grove of pines. The residents for the most part keep their tiny lawns neat and decorate their cement porches with rose bushes or hanging baskets; there is a playground for the children. For the longest time, people here got along: Many of the tenants had grown up in or near Vidor, and they had become even closer as they endured the contempt the rest of the population harbored toward people in the project. Here, everyone was in the same boat. “Everybody knew everybody’s business,” says Ross Dennis, a former resident who now lives in exile in Arkansas. “We knew who looked in windows at night, who sold dope, who paid what in rent.”

But then federal judge William Wayne Justice shattered the peace of the project and, not at all coincidentally, of the town of Vidor itself. For more than five decades, Vidor had been all white, and the government had decided it was time for a change. To resolve a thirteen-year old housing-discrimination suit, Justice ordered that Vidor’s project, along with projects in 35 other Texas counties, be desegregated. At risk was future federal funding of public housing in those regions. The decree seemed to come out of another era, when blacks were forbidden equal access to everything from the lunch counter to the voting booth and the job site, but then, life in Vidor also appeared frozen in time. Not only were there no blacks in Vidor, but there was no trace of black culture. In Vidor there was no Martin Luther King Boulevard, as there was in Beaumont and Orange and Houston. There were no black beauty products in the drugstores; no copies of Ebony or Jet; no black churches; no black civic officials, lawyers, doctors, or garbagemen; no black high school students, teachers, waitresses, cashiers, or shoppers. Most days, the only black people in town were on television.

Blacks had been permanently driven out of Vidor seventy years ago, and for that effort the town had earned an enduring label as a bastion of white supremacy. Or, as it would be called by the Houston Chronicle when the crisis began, “a Klan stronghold.” Or, as it would be called by the New York Times when the crisis deepened, “a hotbed of Klan activity.” As framed by the media, this belated attempt by the federal government to integrate Vidor had little to do with the seemingly hopeless racial problems of contemporary Los Angeles or New York; it seemed instead to echo the civil rights struggles of the sixties. It was a simple story of good versus evil; the government would use its might to break the back of racism in an ignorant, hateful place. There might be angry demonstrations, violent confrontations, and numerous arrests in Vidor, but ultimately, a citizen’s right to live where he pleased would be upheld. Racism would lose; America would win.

But that is not what happened. What should have been another success story became instead a chronicle of failure, having as much to do with good intentions as bad ones. In its simplest form, the narrative went like this: Early this year the Orange County Public Housing Authority, which is funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, attempted to desegregate the Vidor site, as it was ordered to do. The result of the relocation of two single black women with five children between them and two single black men was several months of terror at the hands of various white supremacist groups, unrelenting negative news coverage of the town, and as of last September, the restoration of Vidor to its monochromatic state. The black people who had been relocated to Vidor had relocated themselves right back out again, and one of them, a restless idealist by the name of Bill Simpson, was murdered in the process. Finally, in an unprecedented move, HUD secretary Henry Cisneros seized control of Vidor’s project from the housing authority, vowing that his agency would try again. Soon.

What went largely unrecognized throughout this battle was that the events in Vidor might reveal less about who we were than who we are becoming—that it might say more about our balkanized future than our segregated past. As a great many Vidorians pointed out, their town is surrounded by places where the absence of blacks has not been a cause celebre. Cities like Beaumont, Port Arthur, and Orange—the points of the so-called Golden Triangle—have hefty black populations, but many smaller towns in the region do not. Nederland, with 16,192 people, has 88 blacks; Bridge City, with 8,034 people, has 19 blacks; Mauriceville, with 2,046 people, has 12 blacks; and Lumberton, with a population of 6,640, has only 2 blacks. African American separatist Eric Muhammad, a guest on an October 1992 Donahue devoted to the situation in Vidor, would not see in those numbers a clarion call for integration: “The attempt to coexist peacefully—black and white—hasn’t worked,” he declared on the show. “I take the position that it’s not feasible to move people into an area where they are not wanted, will not be respected, and therefore we are ultimately sentencing them to a death, because they are going into a very hostile environment. It’s insane to move families there just for funding and not give a damn about the families once they arrive.”

Once, integration was regarded as the supreme goal of the civil rights movement. Opening America’s neighborhoods and schools and workplaces to minorities, we believed, would end racial inequities. But almost forty years after the civil rights movement began with Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, and after no small amount of progress has been made, profound racial divisions remain, mired in arguments over everything from class to crime, from education to birthrates. A once indomitable government seems paralyzed in a policy bog of its own, unable to grasp the scope of the problem, much less propose solutions. Seen in this light, the Vidor story changes shape and emphasis: It is no longer a simple fable of a racist town, but a very complicated tragedy of a society that has lost its way—and doesn’t even know which racial ideal to pursue.

Hate had a beautiful day when the white supremacist Nationalist Movement came to host their Victory in Vidor celebration. A little more than a month had passed since the last black person had been driven out of the housing project. The weather was still warm for mid-October, the sky a dauntless blue. Onlookers began pulling into Woods grocery store parking lot across from city hall long before the scheduled two o’clock rally, ignoring pleas from civic officials to stay away. The event was the culmination of months of legal wrangling—attorneys for the Nationalists had threatened to sue if their clients were not allowed to demonstrate, and then they threatened to sue if their clients were not afforded proper security. The cost to the already strapped town of Vidor was more than $50,000; with the tab still running, even locals sympathetic to the Nationalists’ cause were coming to suspect that they were not saviors.

In fact, in the weeks preceding the march, the 12,000 or so residents of Vidor seemed to have unified against all outsiders. The Nationalists, from Mississippi, were just the latest group of white supremacists to descend on the town since the integration efforts began and the Good people of Vidor had had enough—enough of the media’s slamming them as racists, enough of the racists and their First Amendment rights, enough of Henry Cisneros. But most of all, they were sick to death of everyone’s exploiting Vidor for their own ends. To many in Vidor, the good name of their town had been soiled by an inaccurate press and an overzealous government.

The fallout from the integration effort was costing them, and they wanted it all to go away. Interstate 10 travelers now bought gas in Beaumont or Orange rather than stop in Vidor, and anxious business associates called from as far away as Singapore to ask about the situation. One local attorney felt compelled to reveal her Vidor roots during jury selection in Beaumont so that the opposing side couldn’t mention it later. Vidor High School students left their letter jackets at home when they competed against other schools—they were afraid of reprisals. At a city council meeting in late September, citizens poured into city hall to demand that local government refuse to grant the Nationalists a parade permit. One by one, speakers rose to the microphone, many more closely resembling yuppies than the racist crackers portrayed by the national media. “If you grant this permit, you betray the city of Vidor,” declared one man. “Ninety percent of the people in Vidor oppose this parade.”

His statement was inspiring but, unfortunately, a bit optimistic. Civic leaders frequently refer to Vidor as a bedroom community, and indeed, Vidor has over the years made the transition from small town to Beaumont suburb. It boasts some large comfortable homes that would not be out of place in Houston or Dallas, but they are the exception, not the rule. “Bedroom community,” it should be remembered, can also be a euphemism for “no jobs”—Vidor has an 11 percent unemployment rate. It has none of the charming historic structures that link this part of Texas more closely to the South than to the West; the battered shacks and rusting trailers ringing the outskirts of town are small monuments to failure and disappointment. Main Street is comprised largely of fast-food chains and gas stations that serve I-10 traffic; the Wal-Mart, Weiners, and Price Lo Foods are there for the locals. In this atmosphere of poverty and isolation, the old Vidor has continued to thrive.

That particular Vidor, the one that better heeled and better-educated citizens would rather forget, is best observed—as a great many reporters discovered—at Gary’s Coffee Shop. Situated in a Main Street shopping center just off I-10, Gary’s is a vestige of that time when the Ku Klux Klan ruled the town. Here is where old and old-looking men with no place to go take long pulls on their cigarettes and chew over the day’s news: a pastor who has taken to drink, an uncle who waited up for his wife with a .38, and of course, the people who are regularly referred to as “riggers.” At Gary’s it is possible to hear men argue about who is or is not in the Klan, to see men greet each other jokingly with a “white power” salute, to hear a man say that he was “thinking about the riggers” while he was “out hunting for UFOs.” This Vidor was not invented by the media, as some Vidorians would assert; it exists, and it is the one that remains embedded in the consciousness of most Texans—and most racists. Just as Vidor became a symbol to the federal government, it also became a symbol to the white supremacists. If they could not triumph in Vidor, their reasoning went, they couldn’t win anywhere.

It was not surprising, then, that the Nationalists fought so hard to stage the Victory in Vidor march, nor that most of their marchers were from out of town. (The majority were from Houston, the Pasadena and Greenspoint areas.) What was surprising was the youth of the marchers. The Nationalist Movement turned out to be one middle-aged man named Richard Barrett and a handful of kids with skinhead hairstyles. The oldest was nineteen, the youngest thirteen. As they assembled at the city park, easily outnumbered by the press, they dragged on cigarettes and posed for pictures eagerly but self-consciously. A teenage girl explained that she had started the Nationalist chapter in her school because she was tired of violence and gangs, the current code words for “blacks.”

Barrett had all the charm and verve of a high school bandleader. “If somebody has some better slogans, come up with them!” he exhorted his ragtag marchers through a bullhorn. “Neighbors over nastiness! God bless America! God bless the working man!”

As the small crew marched down Bolivar Street to Main, people watched them from their cars, porches, and picnic tables. Some were supportive, but most were derisive. One woman held her daughter in her arms; the child clutched a black Cabbage Patch doll. All three were soon swarmed by photographers. “I just wanted to show everybody that we’re all precious in God’s eyes,” the mother said. “These people do not represent Vidor.”

On Main Street, however, the marchers were greeted by a swelling crowd of about three hundred. No one appeared to like each other much. Pro-integration types screamed at those who were opposed, everyday racists hated nazi types, merchants hated reporters, a group representing the National Organization for Women inexplicably shouted down almost everyone. Many people seemed to be from somewhere else, mainly Houston. The one black person in the crowd was a young man from Houston’s Montrose area who had come to protest the Nationalists’ appropriation of the skinhead style, which he said had been started by blacks. It was easy to lose track of the point.

Across town at the junior high school, the good people of Vidor had staged a prayer rally, their standard response to the pressures of the past year. (“We weren’t speaking against the Klan,” one preacher had noted of an earlier event. “We were just speaking of positive things.”) These crowds had always been bigger than the white supremacists’ gatherings, and today’s was no exception. Twelve ministers in shirtsleeves dispensed religious homilies from atop a huge flatbed to several hundred people seated on the grass. But even with their numbers, this crowd lacked the passion of the assembly on Main Street. No one shouted; even the hymns were reserved. The concluding prayer was innocuous. “Father, we pray that this will not be the end,” a ghostly white preacher began, obliquely citing his hopes for peaceful integration in Vidor. The audience bowed their heads. They were silent, polite, and alone.

The little boy danced across the muddy yards of the housing project like a sprite, barefoot on one of the first cool days of fall. Even though it was after lunchtime, he was still dressed in his pajamas, and everything, head to toe except for his golden curls, was soiled with grime. He did not talk as much as peep, even though he looked to be between three and four. At first he tried to entertain a visitor with his smile, and then by twirling a bright red umbrella he had filched from a neighbor’s yard. Bored with keeping up a charming front, he turned on his heel and spit. Then he laughed.

Such is the conventional picture of Vidor: poor, dumb, and mean. It isn’t far wrong. Born as a logging town, it was named after C. S. Vidor, a prominent lumber mill owner and the father of renowned movie director King Vidor. It was, prior to 1925, accessible to Beaumont only by ferry across the Neches River. The place was hot and soggy, filled with bugs, snakes, and the long shadows of the pines. After work, there was not much for a man to do but drink. Bar fights were part of the culture, earning the town its moniker, Bloody Vidor; like so many outposts where men were spared the civilizing influence of family and community, violence was a recreational sport.

The woods that provided Vidor with industry also afforded another opportunity. When the Ku Klux Klan took hold in Texas in the twenties, people from the nearby cities found the dark, silent pine stands of the Vidor area to be good places for secret societies and secret meetings, and the townspeople—poor, ignorant, and resistant to change—were receptive to the Klan’s insular and angry message. The history of this time is largely anecdotal. Former housing project tenant Joyce Dennis says that her father told her that during the Depression, racial hatred fueled a land war chat raged between Beaumont and Orange; the combatants were the blacks who owned the land, and the whites who didn’t. Over the next thirty or so years, clanks to frequent cross burnings and scattered but steady shootings, beatings, and hangings, the blacks who lived in Vidor were driven out. Dennis remembers the three ropes that dangled from trees near her favorite fishing hole; her father had told her that after a black man had raped a white woman, they had hung two black men “before they got the right one.” It is understandable that more blacks than whites remember a large hand-painted sign that is said to have stood at one end of town: “Niggers read this and run. If you can’t read, run anyway” are the words that some recall. Others remember one that read, simply, “Nigger, don’t let the sun set on you in Vidor.” If there were whites in Vidor who were ashamed of the sentiment, they kept that shame to themselves, afraid of the classic rigger-lover tag and the retribution that accompanied it.

For nearly fifty years, Vidor kept that chip on its shoulder. It was openly hostile to the civil rights movement and impervious to the contempt of outsiders, who breezed through town on the newly constructed I-10, snickering at the hicks in their rearview mirrors. In the seventies, because of school desegregation in nearby Beaumont, white flight found a haven in Vidor, and the place began a slow, steady shift from small town to bedroom community. It wasn’t your everyday suburb, of course: By then, the national headquarters of one Klan group was located in Vidor, along with several other klaverns. A Klan bookstore welcomed shoppers on Main Street, and the Klan catered local functions. Stories persisted of blacks’ stopping for gas and being forced to drink motor oil or just being chased out of town for fun. As late as 1985 a bomb threat was called in to the post office after a black postal superintendent was assigned to Vidor. Though Klan acts were diminishing, the threat remained. “You just don’t want to risk driving up and finding all your plate-glass windows smashed,” was the way one resident explained his lack of opposition to the Klan to the Houston Chronicle.

But the suburbanites who had been gradually slipping into Vidor had brought something new to town: an ambition to tame the place and connect it with the outside world. Vidor’s Reputation: Racist Stronghold or Gardeb Spot? one newspaper headline asked in the early eighties. By then, Vidor could tout itself to newcomers as a quiet religious community that offered a refuge from Beaumont’s big-city problems. Restaurateur Ellis Urbina moved to Vidor from Port Arthur in 1989 and, after establishing a successful business, created the “Thumbs Up for Vidor” campaign to help Vidor escape its past. “People had suffered an injustice,” he said of Vidorians. The trouble came from “the myth that had been placed on it by the history.”

There was only one problem. Vidor was still all-white. Integration of a sort had been achieved: Vidorians worked alongside blacks in the steel mills, paper mills, refineries, and offices of the Golden Triangle. Occasionally a black construction crew could be seen toiling in the housing development on Vidor’s north side. Vidor high school students competed against blacks in Golden Triangle sports events and other extracurricular contests. Even the drug trade that flourished in the area brought the races together: Some Vidorians, including Klan members, were known to do business with Beaumont’s black street gangs. To many people in Vidor, the fact that the town was devoid of blacks was simply an embarrassing and unfortunate fluke, something that would be ameliorated with time. As one Vidorian put it, “Vidor is your basic typical little city except that we’re basically all-white.”

Try as residents might, though, the past had a way of spoiling the town’s redemption. Too many whites—and too many blacks—knew what Vidor stood for. Black high school students whose parents had been threatened could now intimidate the children of white Vidorians; college-educated blacks could look elsewhere for work. And though real estate agents in Vidor had been prepped by the Fair Housing Act to show homes to all comers—and few if any Vidorians objected to selling their homes to African Americans—hardly any blacks showed an interest. “Where is the black community?” a black couple from New Orleans asked the Reverend Kenneth Henry several years ago, when he was selling real estate. When Henry replied that there wasn’t one, the couple abruptly terminated the meeting. “They didn’t even want to look at houses,” he recalled. The town had reached an impasse: The blacks Vidor wanted didn’t want Vidor. For the townspeople, redemption would be much harder than they had ever dreamed.

By October 1992, Mayor Ruth Woods had received plenty of hateful calls about desegregating Vidor, but this caller seemed to have something else in mind. “I beg your pardon?” the mayor asked, not sure she had heard him clearly.

“Do you have any tits?” the man asked.

“I don’t think that is a very nice thing to say,” Woods snapped.

“Just answer the question,” sneered the man.

“You know,” said the mayor, trying to match his tone, “it’s very simple for me to get the police department.”

“Well, who are you?” he demanded, as if he didn’t know.

“I don’t mind telling you I’m the mayor of the city,” Woods answered. The man slammed the phone down but then called back about five minutes later with a more focused message. “Who the goddam do you think you are, you m–f–?” he screamed. “I will assassinate your goddam ass.”

So went life in Vidor in the fall of last year, when it seemed that the entire town was under siege, from the Klan, from the media, and from what sometimes seemed like a wrathful God. Maybe, given Vidor’s history, disaster was inevitable. But maybe the situation might have been different if the integration of the housing project had been handled differently—if the commitment of those in power had been as firm as it had been in other places in earlier times. But that was not what happened here. The integration of the Vidor site was, in fact, a case study in a failure of will, one in which every level of government, from the City of Vidor to the Orange County Public Housing Authority to the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development made mistakes that ranged from simple neglect to outright negligence. “Everybody has been a day late and a dollar short in this situation,” said Tom Oxford, a Beaumont civil rights attorney who is representing the black tenants who lived in Vidor in their dealings with HUD.

The current crisis had its roots in the Reagan administration, which basically dismantled HUD, and the Bush administration, which did little to resuscitate the corrupt and moribund agency. HUD’s neglect, in turn, allowed a system of segregated housing to flourish much beyond its time in East Texas. As a general rule, blacks and whites were assigned to separate public housing; whites were directed to white neighborhoods—or white towns—and blacks were sent to areas that were predominantly black. A desegregation suit, Young v. Pierce, was filed by a black woman in Clarksville in 1980; five long years later, activist judge Justice found HUD guilty of intentional discrimination. HUD lost an appeal, and in 1991, after the agency continued to do nothing, Justice ordered the acceleration of the process. By then Young v. Pierce had become a substantial class action suit (now known as Young v. Cisneros), and attorneys for the plaintiffs were demanding that cities and towns that failed to desegregate be forced to lose federal money designated for public housing. To show good faith, HUD offered to make Vidor the pilot project.

In 1992 the Orange County Public Housing Authority, responding to these pressures, began a frantic search for any black person who would move to Vidor. It sent out 1,300 invitations to people on public housing waiting lists in the Golden Triangle and received a universal answer: no. Too many blacks knew too much about Vidor’s history. Next, the Housing Authority hired a black ex-con with contacts in the black communities in Beaumont and Port Arthur. He had two mandates: to find African American tenants for Vidor’s project—and to keep it quiet. The desire for secrecy seemed to be universal. Officials with HUD, Orange County, and the City of Vidor all agreed. Maybe they meant well—maybe they hoped integrating secretly would diminish the potential for violence as much as it would obscure the potential for embarrassment. But the goal was naive at best. “Anybody who thought blacks could move into Vidor without publicity was ignorant,” said Tom Oxford.

Indeed, some residents of the project had known all about the desegregation plans for months. Richard Stanfield, the chairman of the Orange County Public Housing Authority, had met quietly with members of the complex’s resident council in May 1992. Though Stanfield denies it, resident-council president Ross Dennis later told the Texas Commission on Human Rights that Stanfield told the council he intended to “slide a couple of black families into Vidor in the middle of the night.” Once compliance with HUD was achieved, he reportedly said, he would “slide the black families back out again.”

However, there was soon no need for such secrecy. The man hired to find black tenants announced at a commissioners’ court meeting that he had found four volunteers, but he also used the forum to express concerns about their safety. Officials connected with the plan were furious that he had gone public. Their outrage betrayed a lack of resolve. They were willing to integrate, provided it could be done easily, but they had no will to engage in a public fight for an unpopular cause. No one threw the weight of the government behind the integration effort, as was done in the sixties; there were few warnings to potential troublemakers, and few threats to punish the opposition with the use of force or jail terms. In other words, anyone opposed to desegregating Vidor knew that the coast was clear—and they moved in fast.

Most prominent among the white supremacists to stake their claim on Vidor was the Ku Klux Klan, or rather, two different Klan factions. In recent years the KKK had fractured into something resembling Middle Eastern terrorist cells, each with a different philosophy and personality and each with an enmity toward their fellow Klan members that almost equaled their hatred of their enemies. The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, for instance, were David Duke’s yuppie Klan; members eschewed robes and racist slogans in public. In Texas, they were represented by Michael Lowe, a diminutive part-time carpenter who dreamed of building the largest Klan organization in America. The Knights’ competition came from the Texas-based White Camelia Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, from nearby Cleveland, a more traditional–and more extreme–Klan group headed by Charles Lee. Makeovers to the contrary, both groups were essentially composed of thugs.

By late fall, Vidor was infected with fear. A woman with mixed-race grandchildren was told by two men in Klanlike garb to “get her nigger grandbabies out of town.” The Vidor police suspected that Joel Ray Home, an Exalted Cyclops of the White Camelias, was Mayor Woods’s threatening caller. He was arrested at his home near Vidor by federal agents, who confiscated six hundred rounds of ammunition and several weapons, including an AK-47. The housing project was regularly patrolled by men purporting to be Klan members; there were Klan rallies in and around Vidor and a cross burning outside of town. Local businessmen received calls urging them to support the Klan or face a boycott of their businesses. Lowe visited town frequently, glad-handing at Gary’s Coffee Shop like a man running for office. Meanwhile, the White Camelias showed off their restored Texas Department of Corrections bus, complete with mesh-covered windows. According to Ross Dennis, who was the unofficial mayor of the Vidor project, robed members made no secret of their plans. “There will never be riggers moved to Vidor,” one told him. “Or if there is we will burn the housing project down, so they won’t have anyplace to live.” Inside the bus was a military-style gun rack full of semi-automatic weapons.

It was around this time that the press descended on Vidor too. The story appeared in newspapers around the world, but because of its good-versus-evil spin and its lower-class participants, it was particularly well suited to tabloid TV: Phil Donahue’s October show was quickly followed by those of Sally Jesse Raphael, Jerry Springer, and Montel Williams. The tone was inevitably sanctimonious. According to a reporter from Inside Edition, a program based in racially torn New York City, Vidor “was a reminder that the days of hate are not behind us.”

The good people of Vidor tried to salvage what they could of the town’s crumbling reputation—they held their heads high, they stopped talking to reporters, they held prayer rally after prayer rally. But they had lost control. Vidor was in the grips of its past.

And no black person had even moved in yet.

Brenda Lanus, 27, and Alexis Selders, 28, had been through a lot, but they had never experienced anything like Vidor. The two longtime friends had driven in from Baton Rouge just that July afternoon, hoping to escape the drugs and crime that had infested their families and their neighborhoods. They’d wanted to get off welfare and make a new start for their children; HUD’s offer of an apartment in Vidor seemed the answer to their prayers. When they had stopped at a gas station to ask for directions to the housing project, an attendant told them they were in the wrong place—”No blacks live here,” she said—but they followed the directions, and if they hadn’t glimpsed any blacks among their new neighbors, the whites they had met were nice enough.

But when they took a walk up Main Street, no one wanted anything to do with them. No one would even give them a job application, and people snickered at them behind their backs. At a nursing home close to the project, one woman left them standing in the entrance. The more the women walked, the worse it got. Men leaned out of cars and screamed at them. “Brenda just keep your head up, just keep on goin’,” Selders told her friend. But by the time they returned to the project, Lanus was undone.

“What’s wrong with this little town?” she asked Ross Dennis.

“Why, Brenda?” he asked.

“People called us names—” she began tearfully.

“Bitches, whores, riggers,” Selders cut in.

“Well, Brenda,” Dennis began, “this is Vidor. Didn’t anybody explain to you about Vidor?” The women shook their heads.

By the time Dennis finished his history of the town, Brenda Lanus and Alexis Selders had made a decision: to get out of Vidor as soon as they could. The authorities had failed them before they had arrived, just as the authorities had failed the two black men who had preceded them.

From the fall of 1992 until February 1993, the integration of the housing project had remained a hypothetical. Those in power could continue to believe that integrating the town was analagous to integrating Atlanta or Selma in the sixties, but this was different than integrating a lunch counter or a school. This time the federal government had decided to desegregate a place that, particularly for poor people, had little to offer. Bigotry aside, Vidor had no jobs and no public transportation to places that might have jobs. It didn’t even have a taxi service. A black person with no car in Vidor was, essentially, a prisoner.

None of these factors mattered as long as no African American offered to move to Vidor. The four black families purportedly willing to move in had evaporated in the media-Klan blitz of the fall and winter. A tense waiting period ensued as the search for replacements commenced. Security was beefed up around the project, including the construction of gates, fences, and a new office. HUD shelled out $8,000 a month for the Vidor police department’s overtime hours at the complex. The Klan continued to hold rallies in and around town, while those who either supported integration or simply detested the Klan held opposing prayer rallies. The bureaucrats, being bureaucrats, held seminars on fair housing practices. Thanks to a $308,000 HUD grant, the NAACP, in conjunction with the Texas Commission on Human Rights, invited potential tenants in East Texas to educational talks about racism. Finally, however, the moment was at hand: In February 1993 Richard Stanfield announced he had found a volunteer.

John DeQuir, a 59-year-old disabled cement finisher and the father of ten, was kind and deferential in an old-fashioned way. Unpacking his belongings, he told the press he planned to spend his time watching wildlife programs, taking walks to help his bad back, and studying for his general equivalency diploma. “I never thought about being a pioneer,” he told the Houston Chronicle. “I just needed a place to live.” But it wasn’t long before the news hit that DeQuir had served five months in prison the year before; his probation had been revoked on an aggravated assault charge. Though DeQuir was far from the only resident of the complex to have a criminal past, the cry that blacks would bring crime was taken up again, and Mayor Woods was fuming. “We wanted someone who would more or less be a role model,” she said, revealing a bout of what integrationists call the Rosa Parks Syndrome, “perhaps someone down on his luck who needed public housing.”

That person appeared a few weeks later with the arrival of Bill Simpson. He was an enormous man—seven feet tall and three hundred pounds—soft spoken, thoughtful, and deeply religious. The media christened him a “gentle giant.” Simpson too was disabled: A knee injury and crippling arthritis had given him a slow, stiff gait.

Simpson was a much more complicated man than advertised. His had been a middle-class upbringing—born in California, he was raised in a white neighborhood in Olean, New York. He was college bound when he began drifting, through Texas, Louisiana, to drugs, drink, and petty crime. (He spent some time incarcerated in Louisiana for snatching a purse.) Eventually, he landed in Beaumont, where he found a job managing the Salvation Army soup kitchen. When his marriage broke up, Bill Simpson joined the ranks of the homeless.

Even so, people were drawn to him, particularly members of the street ministry of Vidor’s Central Baptist Church. Belying Vidor stereotypes, church members took Simpson into their homes, and over the next few months, he lived quietly in Vidor and began to rebuild his life. There was a mystery to Simpson—sometimes during services he wept quietly in a back pew—but he commanded respect. Several church members thought he might be a perfect tenant for the project.

After one meeting with Richard Stanfield and another with representatives of the Texas Commission on Human Rights and the NAACP, Simpson, imbued with a newfound sense of purpose, agreed. He moved into the project in March. Later he posed for a Houston Chronicle article with his enormous arms encircling three smiling little blond girls. There is no doubt that most residents of the complex welcomed Bill Simpson. They cooked for him, washed his clothes, and kept him company as spring turned to summer. He was elected to the tenants council, which he used as a forum to argue for drug-prevention programs, parolee counseling, and refurbishing the children’s playground. “God didn’t put me here just to deliver me up to violence,” he told a reporter.

But, from the day he moved in, Bill Simpson was subjected to overwhelming pressures. Media coverage was constant. John DeQuir had not been able to get to his apartment on his first day in the complex because of all the reporters. He responded by simply disappearing to relatives’ homes for days at a time. Bill Simpson lacked that option. As the coverage shifted from news to entertainment, he became a subject for exploitation. In one incident, an Australian TV show invited KKK Grand Dragon Michael Lowe to approach Simpson’s door and ask him why he wanted to live where he wasn’t wanted. Lowe was happy to oblige.

Not that the racism Simpson experienced had to be trumped up. While there were undoubtedly Klan members in the project, Simpson was harassed most by a woman named Edith Marie Johnson. An ex-con (she helped her boyfriend break out of jail) with eyebrows painted on in perpetual surprise, Johnson now denies she ever posed a threat to Simpson, though she acknowledges she did not want blacks in the project. In an affidavit Simpson submitted to HUD, however, he said she never missed an opportunity to douse him in obscenities and racial epithets. “If that goddam f–ing nigger comes into my yard, I’ll kill him with my baseball bat and that goes for those goddam m–f–ing nigger lovers across the street!” he claimed she announced within earshot of himself and several neighbors.

Had he been introduced to Lanus and Selders, Simpson could have warned them about walking the streets. Because he too had no car, he had to walk up Main frequently to buy his food. On two occasions, men driving by announced their intention to get a rope and have a hanging party. “I have been called nigger by people in Vidor more times than I can count,” Simpson wrote in a statement later in the summer. “Obscene gestures by people in vehicles as they pass me is a common occurrence.” But almost as problematic as the racism was the isolation: Not only were there no blacks in Vidor, there were virtually no people who had any experience with blacks. Bill Simpson became a human curio, a freak.

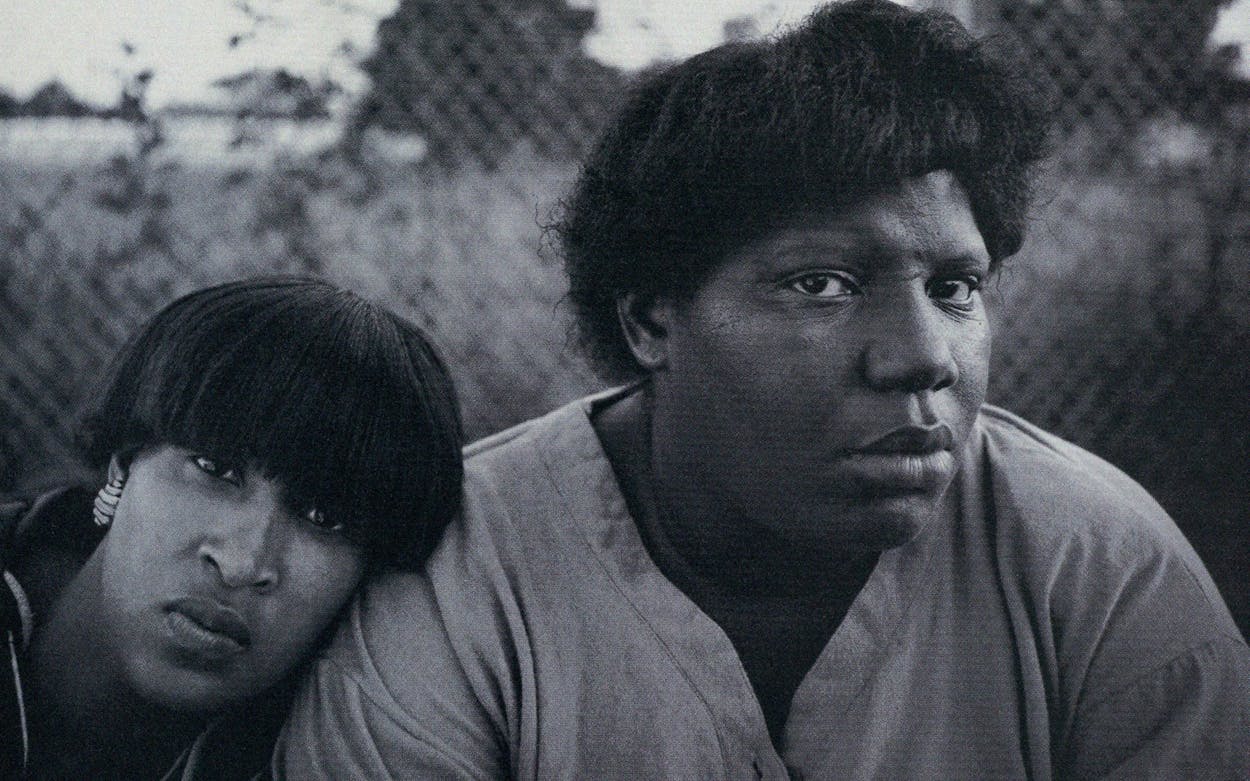

Into this tense, artificial situation came Brenda Lanus and Alexis Selders. DeQuir had essentially abandoned the project because of the pressures; Simpson’s education and upbringing had helped him cope. The two women had nothing comparable upon which to draw. Selders was a wisp of a woman with unwavering religious faith and the regal features of an Egyptian queen; Lanus was tall, heavyset, and very dark, the more analytical and more emotional of the two. Both had dropped out of high school when they became pregnant. They had never been out of Louisiana, never ridden on an airplane, never polished their reading skills beyond the most rudimentary level. It was not hard to believe that Selders and Lanus could be duped by desperate public servants.

HUD representatives had offered the women a U-Haul to help with their move, free telephone and cable hookups, and furniture and groceries once they arrived. Their mothers had been suspicious of all the attention and had urged Selders and Lanus to ask about security, but the two women had been reassured by the office manager that the complex was safe and attractive. “You’re going to have no problems at all,” she had promised. On July 7, Brenda and Alexis headed for Vidor with their children. Brenda’s girls were ages fourteen months, four, and seven. Alexis’ were eight and eleven years old.

Just how much the women really knew about the situation in Vidor remains the subject of no small debate. Representatives of HUD and the Orange County housing authority say the women knew what they were getting into. Selders and Lanus strongly deny that they knew anything of the sort. Bill Hale of the Texas Commission on Human Rights backs them up: “There was a strategic decision made by persons responsible for desegregating the unit not to tell these women about the situation in Vidor,” he says. In fact, the request of the only black member of the Orange County Public Housing Authority Board to meet with them was ignored.

Selders and Lanus’ afternoon stroll had been a preview of coming attractions. They would later complain to the Texas Commission on Human Rights that Johnson had threatened their children with her famous baseball bat that first day, an accusation Marie Johnson denies. (To keep Selders and Lanus in sight of the office, the housing authority had seen fit to move them into units directly across from the worst hatemonger in the complex.) The two women were too frightened to stay alone; that night Selders moved herself and her children in with Lanus. “Why did they have to move us here?” Brenda wondered, peering out the windows at night. Her fears grew once she learned that the security patrols had been stopped two days before—HUD had run out of money.

The next morning the office manager reappeared. She warned the women to keep their children away from Marie Johnson and not to talk to the press. Hearing of their experience the day before, she was apologetic: “Oh, I forgot to tell you,” she said to the women. “Don’t go anywhere alone.” If they needed anything, they were to call her or Homebound Ministries for a ride. In other words, Lanus and Selders were marooned at the project.

The women spent the next few days planning their escape. Ross Dennis introduced the women to Tom Oxford, who filed affidavits with Judge Justice. A black HUD investigator came out to evaluate their claims; as she ambled through the project, a child called her a rigger. She quickly made arrangements to move the women out.

She didn’t move fast enough. A few nights later, teenagers dressed in sheets roamed the project screaming, “Get those riggers.” Until the women got an unlisted phone number, crank calls were constant. Shopping expeditions became a lesson in racial hostility. Lanus couldn’t find any of the hair-care products she normally used—”You have to go to Beaumont for that,” a surprised clerk told her. At a convenience store near the project, a cashier put Selders’ food in a used garbage bag. At the post office, Lanus was standing in line when a clerk frantically ordered everyone out—a bomb threat had been called in. Both women were too frightened to enroll their children in school or even to let them play outside. “They can have this little town” was the quote above the Houston Post‘s coverage of Lanus and Selders’ departure on July 23. They had lived in Vidor for sixteen days.

The women’s exit weakened the resolve of DeQuir and Simpson. DeQuir made plans to move out for good, while Simpson vacillated. He had made friends in the complex, becoming particularly close to tenants council president Ross Dennis, but his fear of Johnson grew daily. Though she now says she never was a member of the Nationalist Movement, Dennis recalls that she frequently bragged about her ties to the group. “It was important that Bill not appear scared,” said Oxford, “but he was scared.” Feeling that he could not depend on local authorities, Simpson, in despair, sent a letter to HUD secretary Henry Cisneros. “As I write this letter, there are five vehicles parked at the residence of Edith Marie Johnson. They are making plans for retribution against myself and the Dennis family for filing complaints against her with the Texas Commission on Human Rights. Because of this situation, we have decided to give up the fight and try to leave Vidor. Neither of us can do any more to further the program and we are trapped by our own poverty in a situation that is very volatile. If we stay, we die; it’s just that simple.”

But then deliverance appeared. A white woman, disgusted by the events in Vidor, offered Simpson an apartment in Beaumont. “I’m really home. I’m finally home,” he said happily on September 1, the day he moved in. He had just enough time to unload his meager belongings and take a walk with two women friends before he was murdered.

Four men pulled up in a car, demanded the purse of one of the women, and then shot the other as she tried to run. Simpson also tried to get away, but he too was shot. When he fell to the ground, one of the assailants stood over him and pumped several more bullets into his body. He died with $2.14 in his pocket.

The Beaumont police immediately labeled his death a random killing and, pointing the finger at a local gang, declared what had happened in Vidor irrelevant. Ignoring the links between white drug dealers and black street gangs, they reasoned that a black person would not have accepted a contract from a white to murder a black. The rumor mill went into overtime: Some said Simpson had been assassinated by four white men who had darkened their skin with charcoal; some said he had been murdered because he intended to blow the whistle on drug dealing in the complex. Some believed that each of the black tenants had received $5,000 for moving into Vidor and that Simpson had been murdered for those fictitious riches. A young man was arrested but never charged with the crime, and an NAACP investigation came to naught. Though the FBI is looking into Bill Simpson’s murder, the case may never be solved.

Meanwhile, Vidor was all-white all over again.

Since they moved to Houston from Vidor, Alexis Selders and Brenda Lanus have become frightened of new and different things. They had wanted to come here, but now their knowledge of the place was coming from Brenda’s small black and white television. Every day, a new murder absorbed them, a new neighborhood was identified by the location of a body. “I’m scared of people around here,” Alexis said. “It’s nuthin’ but killin.'” Both were weary of bureaucrats and reporters who disappeared after doing their duty. “Everybody acts like they want to be our friends and then we never see ’em again,” lamented Brenda.

A penitent HUD had placed them in Section Eight housing, where the government pays for living spaces outside public housing projects. Now the women lived in apartments in a remote part of town connected to the rest of the city by only one bus line. The neighborhood was poor and racially mixed but predominantly black; so, too, was the apartment complex. Their new address remained a secret. They feared retaliation.

Away from Vidor, they had the same old problems. They had no lack of ambition but a lack of knowledge, no lack of opportunity but a lack of the skills to take advantage of it. Taking a tour of Houston, Brenda and Alexis made it clear that they would rather look for jobs than sightsee. They were not particularly interested in architectural sights like the Transco Tower, except to ask whether there might be janitorial openings there. The size and scale of the River Oaks mansions belonging to nabobs like Oscar Wyatt, Gerald Hines, and Bob Lanier inspired only one question. Fiddling with a car door handle while parked in front of Wyatt’s home, Alexis asked, “Can we go up to the door and ask them for a job?”

These women were not without gifts: Alexis’ standard greeting—”What’d you cook last night?”—reflected a brilliance in the kitchen, and Brenda’s determination—she had called every temporary employment agency in the phone book with no luck—revealed an iron will. But both had lost a shot at telephone solicitation jobs because their reading skills were not good enough. They could not pass a simple test that asked them to find the opposite of words like “chaos.” On top of that, their kids were having problems: Alexis’ older daughter remained the honor student she had been back in Baton Rouge, but the younger girls were way behind the Houston Independent School District’s less-than-demanding standards. Teachers wanted to put them back several grades. Alexis had an additional dilemma: She was six months’ pregnant.

While the effort to integrate Vidor might have furthered a principle, it did nothing for the people who unwittingly served as symbols for it. Bill Simpson is dead; Brenda Lanus, Alexis Selders, and their children are, if anything, worse off than they were before—broke, frightened, close to demoralized. The Vidor project was an integration effort in a vacuum, finally an empty gesture.

In the past thirty or so years, few have been willing to admit that the meaning of the word “integration” has changed. It now means much more than putting people of different colors together; it means taking a deprived class of people and teaching them the most rudimentary rules of our society. No attempts were made to integrate Lanus and Selders into Vidor—not just to protect them from harm, but to educate them, to provide them with jobs or at least job skills, to expose them to the entire spectrum of people who make up a community. Without such help, they and their offspring will remain unwanted neighbors no matter where they live; cut off from the rest of us, they will continue to slip farther and farther from society’s grasp. Faced with that truth, it is no surprise that the government continues to be absorbed in the more manageable task of attracting more black families to Vidor. Perhaps it is time to shift priorities.

Trawling the Galleria for work, Lanus and Selders encountered the same old story. The people were kind; receptionists proffered job applications and said they were hiring, but other applicants had longer work histories and other applicants had telephones. Stuck with a $140 unpaid phone bill from Vidor, Selders and Lanus could not yet afford to have a telephone installed at their Houston home. Brenda thought about Christmas and her face clouded; she did not want her children to see other kids taking the remains of their gaily wrapped packages to the trash.

The high point of their day was the arrival of the mail. They had wound up on poor people’s mailing lists—virtually all of the correspondence involved offers for easy credit and sweepstakes. They entered the contests passionately. It was the only place where their odds were as good as anyone else’s.