This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

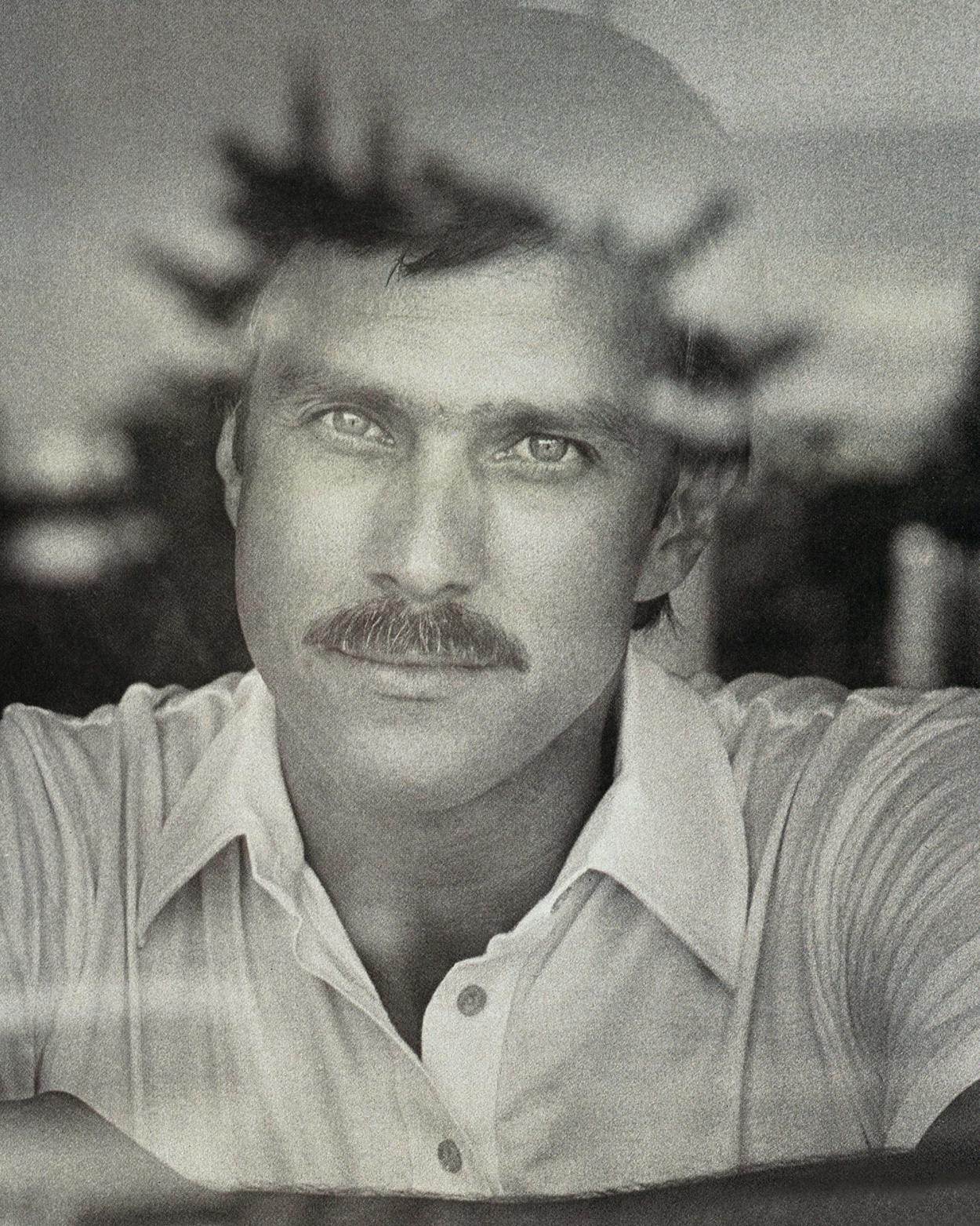

When I first saw Robert Hicks that cold day last November in the visitors’ room at the Federal Correctional Institution in Fort Worth, my impression was that he shouldn’t be there. Some people wear the aura of prison like skin, like something they are rather than something they merely occupy. But not Hicks. He was as smooth and ageless as a photograph in a yearbook. You know the type. Most popular, maybe. Most promising, probably. Most congenial, absolutely. Bright, charming, ambitious, ridiculously handsome—magnetic blue eyes and an impish smile that makes men sit up straight and women quiver. He had been a womanizer and a hard drinker when he started serving his sentence here sixteen months ago, yet now, at age 34, there wasn’t a blemish, a wrinkle, a trace of fat. When he shook my hand, I felt the sincerity all the way to my shoulder blade. First impressions can be dangerous.

I had gone there with an old friend, Joe Hardgrove, who was also a close friend of Robert Hicks’. Fifteen years before Hicks graduated from Texas A&M and went out to make his mark on the world, Hardgrove was a star basketball and baseball player for the Aggies. He was a natural-born celebrity, outgoing and generous, exactly the sort of person who would have attracted Hicks. Hardgrove had become like a big brother to Hicks, standing by his younger friend through all the troubles and trying his best to understand them. “I think you’ll like Robert,” Joe told me. “He’s basically a good kid. He got seduced by the system.”

From the outside the sprawling minimum-security prison looked like a forties hospital or a monastery. It had once been a lockup for drug addicts, back when most of the addicts were either bums or celebrities—before the middle class took over.

The visitors’ area was functional and institutionally seedy. It had a snack bar, a large, plain sitting room with chairs, tables, and a few old sofas, an outside patio, and a children’s playground. Beyond the visitors’ area was a giant quadrangle where inmates of both sexes strolled or mingled in groups as they might on a college campus or at a shopping mall. Only the guards wore uniforms. There were no bars, no guard towers, no tight-lipped block bulls with sawed-off shotguns. The guards were armed instead with two-way radios, which they used to summon inmates from other units. “Freedom Unit,” a woman guard spoke into her radio. “Robert Hicks has visitors.”

While we were waiting for Hicks, I told the guard that when Hardgrove and I were kids growing up around Fort Worth, we heard the rumor that Peter Lorre was doing a stretch out here. “We were duly impressed that a celebrity was among us, so to speak,” I told her.

“They’re all celebrities now,” she said.

Her point was well taken. This was not a warehouse for the vermin and scabs of society’s underbelly but a lockup for the elite. Most of the prisoners had succeeded at something else before they aspired to succeed at crime. Their crimes were neither violent nor abhorrently offensive but, like the crime committed by Hicks, more on the order of betrayals of trust.

Robert Hicks was a celebrity all right. His victims had been major universities and some of the largest, most powerful corporations in America. He shook the college fundraising industry and caused Exxon and other corporate giants to drastically alter the guidelines that dictate the way they hand out money. The name “Robert Hicks” is still a dirty word at his alma mater, Texas A&M. He not only cost Aggie jocks several hundred thousand dollars but he also tried to get the IRS and the National Collegiate Athletic Association on their case by writing incriminating letters. All in all he got away with about $600,000 and was ultimately sentenced to 21 years in prison —more than some confessed murderers get.

But even knowing all that, I liked Hicks immediately. He was charming without being cloying, and there was an almost childlike openness in the way he talked about his crimes. I had never met anyone with a quicker mind or a better memory for detail. He snapped off exact dates, telephone numbers, complicated spellings of places and people’s names, bits and pieces of the U.S. Criminal Code and IRS tax laws, odd insights into what made people greedy, and how that knowledge could be used for good as well as evil. Corporate buzzwords, like “arm’s-length transaction,” slipped from his lips as smoothly as they would have fitted into the minutes of a board meeting.

“I did all the things they said,” Hicks told me. “But I had a lot of help. That’s all I’m trying to get across. I know enough to blow the bleeping lid off the whole college fundraising industry.”

We talked for several hours that first day, and though it was difficult to follow much of what Hicks told me, my instincts said he was telling it straight. I began to understand what Hardgrove meant about Hicks’ getting seduced. Hicks wasn’t the only one who had stood to profit from the fundraising schemes; the schools were getting fat too, or so they thought.

“What did you think?” Hardgrove asked later, as we walked to the parking lot.

“Amazing,” I said. “What did Robert major in at Texas A&M?”

“Business management,” Joe said, and we both laughed.

It is not stretching the point to say that the scam started as a college prank. Just a way to generate money for the old school and get a few football tickets and some recognition from peers. Just a way to blow off steam and have a little fun with the system. What the hell, everybody was writing it off anyway. Who got hurt? Who besides Robert Hicks, that is.

Soon after he graduated from A&M in 1970, Hicks worked as a financial analyst for Gulf Oil in Jackson, Mississippi. That was where he learned about corporate matching grants. Gulf’s policy was to match gifts at a ratio of two to one. Hicks mailed twelve postdated, personal checks of $30 each to the A&M Association of Former Students, and the grant pushed his donation above the $1000 necessary for membership in A&M’s prestigious Diamond Century Club. “You can’t believe the doors that opened,” he told me.

After a couple of years he got bored with Gulf and moved back to Franklin, where he had grown up. Forty-five miles from A&M, Franklin was one of those small farming towns that lay within the shadow of the university. Apart from the Baptist church and the federal government, A&M was the dominant institution, perhaps the most visible symbol of authority in that part of the state. Hicks opened an auto parts business, got married, and apparently settled down. But he hated his marriage almost from the start, and he loathed his hometown and felt trapped. Once he was divorced, he moved closer to his alma mater, back where the action had been. He kept the auto parts store, but in the summer of 1979 he moved to Bryan and bought a house on Apple Creek Circle. An ex-Aggie who knew him then told me, “Don’t ask me why, but Hicks was trying to crack that clique of saps that runs things at A&M.”

As it happened, the house that Hicks bought was across the street from the home of Dr. B. Daniel Kamp, an acquaintance who was an extension specialist in the Department of Recreation and Parks at A&M. Kamp had grown up in a small town in West Texas, but there was a dash of urban sophistication in his style—the fancy boots, the dark glasses, the prominent moustache, the way that people who had once called him Billy Dan now called him Doctor. Kamp’s wife, Marihelen, was an intelligent, plain-looking woman in her forties. She was working toward a doctorate at A&M and raising their teenage daughters. Robert Hicks in time became like a member of the Kamp family. He ate most of his meals with the Kamps, and eventually Marihelen would divorce her husband and take Hicks’ side.

The Kamps had done their undergraduate work at Texas Tech, and they shared with Hicks the tribulations and absurdities of postgraduate life in the stifling atmosphere of a conservative college community. Hicks and Dan Kamp became drinking buddies and constant companions. “They were like brothers,” Marihelen recalled. They were also part of a group of young college professors, businessmen, lawyers, and financiers who called themselves the Poets. The name was an acronym for “Piss On Everything—Tomorrow’s Saturday.” There was a meeting of the Poets’ board of directors at a local watering hole each Friday afternoon. If you called any of their offices that day, a secretary would say, “I’m sorry, he’s at a board meeting.”

For the next two years Hicks commuted between his house in Bryan and his store in Franklin. Since he made no secret of his hatred of his hometown, it seemed strange that he would continue to do business there, but he depended on the recognition and respect that the Hicks family had established in Franklin. Robert’s father, Carlton Hicks, had owned the local Chevrolet dealership before his death. Hicks’ mother, Marjorie D., was clerk of the district court in Robertson County; an older brother, John, was president of the First National Bank and a pillar of his church.

Robert had been president of the local chamber of commerce and was known for his charitable work, especially with a group that raised money to remodel the high school football stadium. Though Robert was not exceptionally wealthy, he was more than just comfortable. In addition to the auto parts store, he owned three car washes and real estate, including part of the family farm that Carlton Hicks had bequeathed to his wife and sons and daughters, four of whom had attended A&M. Robert was the most rebellious of the five Hicks children. He dropped out of the cadet corps after his first year at A&M. He had never shown much interest in family business, and after his father’s will was probated Robert turned his part of the old farm into a playground for his college pals.

Hicks liked to show off for his friends. He drove a Cadillac and enjoyed waving fistfuls of money under the noses of cocktail waitresses and airline hostesses. Beautiful women seemed to fall at his feet, and though he misused them blatantly, they never seemed to get enough. His plans, though at all times mysterious, were unfailingly grand. He always had tickets to A&M football games and invitations to pregame brunches sponsored by the Twelfth Man Club, whose members had each contributed $2000 to the Aggie athletic program.

In the early part of 1981 Hicks created a small sensation among his contemporaries by making a substantial donation to A&M. The figure that Marihelen Kamp and others heard was $25,000, earmarked for the business school. Friends recalled that there was a luncheon and a plaque and even a room at the business school named in his honor.

Money to Burn

On my second visit to the Federal Correctional Institution, Hicks told me in detail about the $25,000 donation. The $1000 gift he had made when he worked for Gulf may have opened a few doors, but this gift kicked them down. It wasn’t just an annual donation to an alumni group, it was a gift through the A&M Development Foundation on a par with the prestigious permanent presidential endowments. Some of the same people who had raised money for the alumni group had moved up to the foundation, and Hicks had maintained contact with them. He had also kept ties with the business school, with the intention of eventually making a large donation. Now the time was right. The problem, of course, was that Hicks no longer qualified for a corporate matching grant. That was when he came up with the idea of donating the money through a second party, someone who was eligible for matching funds. Hicks remembered the inspiration vividly; he called it “finding the mother lode.”

According to Hicks, he discussed the idea with people at A&M, and they were receptive. “Just make sure it’s an arm’s-length transaction,” Hicks remembered being told. He thought of using an uncle who worked for Gulf, but the uncle refused. Finally he settled on a former Aggie who worked for Exxon. I’ll call him Jim Ed Wolcott.

Over the next two calendar years, Hicks told me, he gave two checks of about $3000 each to Jim Ed Wolcott. It was necessary to make the donations over two years because Exxon, like most corporations, will not match gifts of more than $5000 in any given year.

“Here’s how it worked,” Hicks told me. “I gave the money to Wolcott and took it off my income tax. Wolcott gave it to A&M and took it off his income tax. Exxon matched it three to one and took it off its income tax. Everyone knew about the deal, and everyone was happy. They put our names in the newspapers, gave us plaques, even named a room in the business building the Hicks-Wolcott room.”

Assuming that Hicks had money to burn, everyone converged on him with requests for various causes. Among those who approached him was his neighbor Dan Kamp, who was involved in founding the Brazos Valley Chapter of the Texas Tech Ex-Students association.

Kamp introduced Hicks to another Texas Tech graduate who worked with Kamp at A&M. In the summer of 1981 they persuaded Hicks to make a contribution to Texas Tech. Why they thought Robert Hicks would be interested in giving money to Texas Tech has never been made clear—but they did and he did, and the scam was off and running.

The deal that Hicks struck with the ex-students association at Texas Tech sounds like the old pigeon-drop routine. He persuaded the exes to give him $15,000 and promised that he would match the money three to one. At that point Hicks hadn’t intended to profit from the scam. He just wanted the attention. He got a woman friend who worked for Exxon in Houston to give him the names and Social Security numbers of Exxon employees. Then, without their knowledge, he donated the $15,000 back to Tech in their names and got Exxon to match it.

While Hicks was waiting for Exxon’s matching-grant check, he formulated the key part of his scam almost accidentally. He told me that he and Kamp were drinking at Hicks’ house one afternoon in the late summer of 1981 when the thought of a free trip to Hawaii crossed his mind. “Let’s try this same deal on the University of Hawaii,” Hicks suggested. “Maybe they’ll fly us over there.” He telephoned the director of the University of Hawaii Foundation and pretended to be a wealthy Texan looking for a place to spend his money. The figure Hicks mentioned was $15,000. “Hell, that was just one little Exxon matching-grant form,” he told me. The director of the foundation seemed impressed and promised to call back.

“When he called,” Hicks continued, “he said they had this project that needed funding, but it would cost one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars. I thought, damn, this guy is really brash. Then it hit me. If he’s brash enough to ask for one hundred and twenty-five thousand, maybe he’ll agree to loan the money back to me at ten per cent interest. So that’s how the idea was born. That was the forerunner of the deal with Texas Tech, the Bishop College deal, everything.”

Though the scheme that finally evolved defies all logic, administrators at three different schools bought variations of it anyway. Essentially it worked like this. Hicks would agree to donate or at least raise a large sum of money for the school, and the school would in turn agree to loan the money back to Hicks for ten years at 10 per cent interest. From the school’s point of view, that made sense because it would be receiving Hicks’ interest payments on money it otherwise would not have, and eventually the school would get the principal. Once the terms were agreed on, Hicks would start a shell game between himself, the university, and the corporations. Typically, he would donate $5000 of his own money in the name of a retired corporate employee. The university would mail out matching-grant forms to the appropriate corporation; the corporation would check its records to certify that the employee was indeed eligible and would then mail its own check. In the case of Exxon, which matched gifts three to one, the initial $5000 check would be matched by a second check of $15,000. In the case of Texas Tech and Bishop (the Hawaii scheme was more complicated) the total gift ($20,000) would be mailed to a special account that Hicks had opened at his brother’s bank in Franklin. The money was Hicks’ to do with as he pleased.

Once the pump was primed and the money was flowing, Hicks didn’t even bother sending his original gifts to the university. He simply telephoned or wrote the school that another gift check had been deposited in Franklin. Incredibly, the universities never bothered to check their bank statements and therefore had no way of knowing that the original gifts did not exist. Apart from the initial $5000, the only real money that ever existed came from the corporations’ matching grants. There was a flaw in the plan, of course; eventually Hicks would have to pay back the loan. But Hicks wasn’t the type to worry about things that far in the future.

As Hicks had anticipated, the foundation director at the University of Hawaii was so eager to get his hands on the money that he didn’t ask a lot of questions. A short time after that first phone call, Hicks and Kamp flew to Honolulu to discuss the project. Hicks introduced his friend as “my colleague, Dr. Kamp,” and though Kamp denies any knowledge of Hicks’ scam, his presence must have lent a certain credibility to Hicks’ story. The project that he agreed to fund was called the Pacific Islands Monograph Series, and it was related to Kamp’s area of expertise in tourism and recreation.

After Exxon’s grant money was received by Texas Tech in October, Hicks made a presentation at a private luncheon in the office of Dr. Lauro Cavazos, president of the university. At the same time, he made a much larger proposal. Hicks would donate $100,000, if the university would agree to loan the money back for a period of ten years. A few days later Dr. Bill Dean, executive director of the Texas Tech Ex-Students Association, wrote to Hicks that neither he nor Dr. Cavazos “has any problem with the arrangement in the proposal.” Hicks could invest the money as he saw fit, though their agreement added that the investments “shall be arm’s-length transactions based upon sound business principles.” I don’t know what “arm’s-length transaction” means, but in practice it meant that Tech made no effort to find what Hicks was doing with the money.

That same month, October 1981, Hicks was honored at the halftime of a football game between Texas Tech and the University of Washington. Bill Dean presented a plaque to him, and another plaque with his picture on it was hung on the wall of the ex-students association trophy room. Hicks watched the game from the presidential box, and he met dozens of influential Texas Tech backers, including a prominent Catholic who suggested that the pope might be prevailed on to bless Robert Hicks.

Hicks was having the time of his life, flying all over the country, meeting important people, and seeing his name in print. That may not have impressed some people, but it impressed Hicks. The money was great, but early on at least, the money was secondary. He was doing it for the glory.

That only seems more bizarre because during the same fall, Hicks realized the scam was going to blow up in his face. He was at an Aggie game at Kyle Field when he opened the football program and saw that Jack G. Hester was listed as a $2500 contributor to the Twelfth Man Club. Hicks had never met him, but he knew that Hester was a former employee of Exxon. One of the names he had used to generate the original Exxon gift to Texas Tech was “Jack G. Hester.” Hicks knew that sooner or later Exxon’s computer would discover that a former employee had exceeded the $5000-per-year limit on matching grants, and then someone would start asking questions.

A Need for Revenge

A number of things went through Robert Hicks’ mind on that fateful afternoon at Kyle Field, but shutting down the scam wasn’t one of them. On the contrary, he had plans to expand it. At first he thought about reimbursing the Twelfth Man Club for Exxon’s part of Hester’s donation, then he realized that would cause suspicion rather than divert it. He thought about writing Exxon, explaining that it had all been a mistake. He thought too about Costa Rica, where he had already arranged a safe haven if he got caught. “I was well wired down there,” he told me. “There’s no way the government of the United States could have ever gotten me out of there.”

Finally, he decided to do nothing, to just sit there in those excellent stadium seats that his club membership provided and enjoy his private joke: though he had signed a pledge with the Twelfth Man Club and took advantage of all its privileges, he had never gotten around to paying the pledge, and he had no intention of doing so.

There was a contradiction about Robert Hicks that I cannot explain, one that surfaced nearly every time we talked. On the one hand, he knew from the afternoon he saw Hester’s name on the football program that his days were numbered; on the other hand, he was absolutely convinced that he was on a roll. There was something self-destructive about Robert, but I couldn’t get a handle on just what. He was exceptionally bright, but he could also be exceptionally childish, as though he believed he could wash away any deceit or act of cruelty with a smile.

I occasionally wondered why Hicks was so eager to tell me his story. At times he seemed to be confessing, at other times accusing. He went out of his way to incriminate others, and invariably they were the people closest to him. I didn’t know if he was just trying to spread the blame or if there was some deeper need for revenge.

No one except Hicks knew how many irons he had in the fire during the autumn of 1981. He was making frequent trips to Lubbock, sometimes alone and sometimes with Dan Kamp, and he was often flying to Honolulu. Kamp made at least two trips with Hicks to Hawaii, and from time to time Hicks took along other friends, paying their travel expenses with the money coming in from corporate matching funds. “Did you ever see that juggler on the Ed Sullivan Show, the one that would get all those platters twirling on all those poles?” Hicks said during one of my visits. “That’s the way it was with me.”

Federal agents never learned how Hicks got the names, Social Security numbers, and sometimes corporate ID numbers of the retired employees that he used to generate the flow of money. Hicks told me that the information on Exxon employees came from a woman friend who worked for the company in Houston. The others required more imagination. Hicks learned that most corporations published newsletters for former workers, and he got himself on the mailing lists of about twenty of them. With names like the Gulf Oilmanac or the ARCO Spark, they published gossipy items about who was living where and doing what. Hicks would telephone a retiree and say he was calling from the corporation’s employee relations department—just checking to see if the retiree was getting his newsletter and maybe his pension check.

“These people were unbelievably lonely,” Hicks said. “They were damn glad to be talking to anyone from the old company. I’d bullshit them around a little. If they had complaints, like if their pension checks were late arriving, I’d get this very concerned sound in my voice and promise I’d check it out first thing.” Gathering the information he needed to fill out matching-grant forms was no problem for a con man with Robert Hicks’ talents.

There was a note of daring, of recklessness, even of arrogance, to Hicks’ activities. Some of his schemes were planned with great precision, but others were incomprehensibly impulsive and spur-of-the-moment. Robert was impressed by famous and influential people, and they usually brought out the worst in his character. In December 1981, for example, while attending a birthday party for Lady Bird Johnson on the University of Texas’ Austin campus, he learned that UT was only $20,000 short of the funds needed to endow a $1 million chair in honor of President Lyndon Johnson. Hicks pledged $20,000. Naturally, there was much elation, and lots of people crowded up to shake his hand.

Of course Hicks never came across with the $20,000. Instead, he attempted to negotiate with the UT Development Office, apparently proposing a scheme similar to the one he had sold to Texas Tech and the University of Hawaii. UT turned him down. So did Baylor.

Duping rich and powerful institutions was one thing, but what Hicks did next seemed mean-spirited and cruel. In January 1982 Hicks contacted John Dvorak, executive assistant to the president of Bishop College in Dallas. Bishop was a world apart from the major universities that Hicks had been conning. The campus looked like a combat zone—empty buildings with broken windows, a student center in poor repair with heavy chains securing outside doors, and fields of weeds and high grass. Hicks had done his homework; he knew that Bishop was in chronic financial trouble. Three key officials had been indicted in a scandal in 1978, and the school had been struggling to survive ever since.

Hicks told John Dvorak about a wonderful coincidence—“a prayer answered,” Dvorak called it later. Hicks invented a story about how he had spread newspapers across the floor to varnish furniture, and while he was down on his hands and knees he happened to see a story about singer Lou Rawls and the annual United Negro College Fund telethon, which benefited Bishop and 41 other black schools. Hicks made a pitch about “a great social statement” and added that it was his belief that “donating money to your own alma mater is not really giving.” The figure Hicks mentioned was $100,000. Officials at Bishop were overwhelmed at what appeared to be a turn in the school’s fortune, and they quickly agreed to the same proposal Hicks had used on the other schools.

By May 1982 records at Bishop showed that $217,500 had been deposited in the Bishop Endowment Fund account that Hicks had opened at his brother’s bank in Franklin. Unfortunately, Dvorak didn’t check the monthly bank statements. The only money that had been deposited was the matching funds that Bishop so obligingly sent along. Hicks continued to mail corporate matching-grant forms to Bishop, and the college continued to mail the funds to Hicks until December 1982, when the school learned that Exxon was conducting an investigation.

The Master Plan

There was a time in the beginning when Hicks believed that he could back away from the scam anytime he wanted, but by the spring of 1982 he was hooked, and he knew it. Each new scheme was more reckless, more brazen, than the one before. Hicks was drinking heavily, and the booze gave him false courage. More than that, though, he was intoxicated with success.

Early that year Hicks contacted his half brother, Fred Eden, and asked him to come back to Franklin and help run the business. Not the auto parts business or the car washes—this was something much grander, an empire in which Eden would act as “property manager” and scout for acquisitions. At first he wasn’t interested. He had lived in Houston for years, and he wasn’t eager to return to a small town. But when Robert offered him $2500 a month plus expenses, Eden yielded.

The executive offices of Hicks’ empire were to be in an old building that Hicks planned to purchase and remodel in downtown Hearne. The building, owned by the United Bank of College Station, had housed the bank before it moved to College Station in 1980. There had been a scandal at the bank in 1974 in which officials were indicted. The scandal and the lack of growth in Hearne had prompted the bank to move, and now the building was on the market for $300,000. James E. Scamardo, the bank president, knew the Hicks family and quickly agreed to sell the building to Robert. John Hicks believed that the building was a white elephant, and he advised his brother against purchasing it. But Robert used $100,000 from the Texas Tech Ex-Students Endowment Fund as a down payment and agreed to pay or refinance the balance in a year.

The building was part of the master plan that Robert was formulating. Among the operations he envisioned was a clearinghouse or brokerage firm for noncash gifts that were accumulating at various university foundations. It was a legitimate enterprise, addressing a legitimate need. Many schools around the country have a surfeit of gifts that they can neither use nor readily dispose of—airplanes, boats, heavy equipment—almost anything that an alumnus doesn’t need except as a tax write-off.

Every time I talked to Robert, he brought up that run-down, white elephant of a building in Hearne. It seemed a most curious location to broker yachts and DC-6’s. Even if the building had been a bargain, the town of Hearne wasn’t. Why not headquarter his future empire in Houston or Dallas, or New York for that matter? Robert didn’t have an answer, or if he did, he couldn’t articulate it. The contradiction was made more baffling by the passion that he felt for that old building. The equation didn’t balance. If he hated Franklin so much, why did he do business there, and why would he want to do business in Hearne, just thirteen miles away? Was he trying to prove something? What? And to whom?

Hicks had one immediate need for the building, however. He planned to use it as part of the collateral for a $1 million loan he hoped to obtain from the Texas Tech Foundation. In March 1982 he made a proposal to the foundation that was so incredibly complicated that no one, not even Hicks, understood it. The proposal involved $2,951,000, which would accrue to the use and benefit of Texas Tech over a period of ten years. It also involved a $1 million loan from Texas Tech, which Hicks would repay over ten years. Hicks told me, “I just sat down one day and started plugging in some figures, and lo and behold, it added up.” It did not add up, however, for the executive committee of the foundation, which turned it down. John Bradford, the foundation’s director, said, “Fortunately, our board didn’t fall for it. One of our board members, who was a real entrepreneur, told the board that if he couldn’t understand what Hicks was proposing, there had to be something wrong with it.”

By late August 1982 it was obvious, at least to Hicks, that the scam was breaking apart. Just as he had expected ten months earlier, Exxon had discovered that Jack G. Hester had not donated $5000 to Texas Tech, and the company was conducting an audit of its matching-grant program. In December, Dr. Bill Dean demanded that Hicks return all the money. A few weeks after that Hicks disappeared. From January to April 1983, Robert hid out in Laguna Beach, California, while federal authorities gathered evidence and indicted him. He kept thinking of skipping to Costa Rica, but for reasons he couldn’t explain even to himself, he never did. My guess is that Robert didn’t believe a jury would convict him. At any rate, he turned himself in.

Shortly before the trial started in June, federal prosecutors offered what, in retrospect, was an extremely fair deal for a plea of guilty—a five-year prison term, providing Hicks made full restitution. “The problem was,” Houston defense attorney Wendell Odom explained, “they wouldn’t give Robert time to assemble his assets. There was no way he could make restitution that fast.” Odom conducted a defense based on mitigation in punishment. There was no denying that Hicks did the crime, but Odom tried to show that the defendant had had a lot of help.

“You have to use your common sense,” Odom told the jury. “Robert Hicks didn’t get into this thing by himself.”

Odom wanted to call Marihelen Kamp as a witness, but Hicks would not allow it—why, no one knows. Dan Kamp testified that he knew nothing of matching funds. But a year after the trial, shortly before Marihelen filed for divorce, she wrote to the presiding judge, Robert Hill, saying she felt the truth had not come out in the trial. According to federal prosecutors, the letter was turned over to the FBI and to the grand jury in Hawaii.

Even the prosecution was surprised at the length of the sentence imposed by Judge Hill and the urgency with which the judge insisted Hicks begin serving it. Hill ordered the marshal to take Hicks away immediately. After the sentencing in Dallas, Hicks was transferred to Hawaii, where he entered into a plea-bargaining agreement with the government. Though he didn’t testify at the trial in Dallas, Hicks insisted on telling his story to the grand jury in Hawaii. He delivered a list of names of people who, he said, had helped with the scam. The list contained seven names, including his best friend, Dan Kamp; his brother, John Hicks; his half brother, Fred Eden; and James Scamardo, the president of the United Bank in College Station who had financed the purchase of the building in Hearne.

College Station Con Man

Joking one day, Joe Hardgrove and I realized that Robert Hicks had become something like a comic book character. Captain Invincible, we called him. There was no reality check when you talked to Hicks. I would ask about some aspect of the scam, and before I could stop him, Hicks would launch into a long, extraordinarily detailed story about some undercover operation he was working on in prison. He furnished me copies of memos that he had written to the FBI and copies of memos that the agency had written to him. I had seen enough FBI memos to recognize that they were authentic. Whatever game Robert was playing, it was extremely dangerous. Some of the documents related to information he had gathered on a plot to assassinate a federal judge. Others pertained to exposing a drug ring operated by Dallas bankers. Still others supplied information about underworld hit men.

Even the walls of federal prison were not barriers for the capers of Robert Hicks. Shortly before Christmas 1984 he telephoned Hardgrove at his office in downtown Fort Worth. Hardgrove asked where he was calling from; Hicks said he was in the Calhoun Street Oyster Bar just down the street. He showed up at Joe’s office a few minutes later, with government documents and a story about how the FBI was going to release him from prison to search for the Brink’s robbery fugitive Marilyn Buck—Hicks knew Buck’s family in Franklin. “He was wearing aviator sunshades and a three-piece, powder-blue suit,” Joe told me. “He was dressed like a caricature of a con man—not a Houston con man, a College Station con man.”

Hicks had told Hardgrove and me in November that he was “working a deal with the FBI” to be free by February. In February he said he would be getting out in April, and in April the date was June. The last time I talked to Hicks the release date was definitely December 1985.

I liked Robert and, to an extent, trusted him, but his stories and sometimes his actions were so bizarre, so far removed from common experience, that I began to wonder about my own judgment. There was one thing I knew for certain about him, one thing I knew from the start—he was a con man. Hicks admitted that. But that is a deceiving piece of information. It is easy to believe, but it is not so easy to understand, much less remember. An actor friend once gave me sound advice: “Never forget one thing—that I’m an actor.” So long as I kept that at the front of my mind, we got along fine. We all have a little actor in us, a little con, but we don’t practice it as a way of life. When you meet someone who does, watch out.

Everything Hicks told me had to be checked out. I decided the best place to start was at the beginning, at A&M. I remembered what Hicks had said about the first $25,000 gift, the one Exxon had matched believing that it originated with its employee, Jim Ed Wolcott. Hicks had described it as the mother lode.

After a few phone calls, I learned that Wolcott lived in Corpus Christi and still worked for Exxon. He wasn’t home when I called. I talked to his nephew, who remembered Robert Hicks, and later to Wolcott’s wife, who didn’t. Neither of them remembered anything about a $25,000 donation to A&M’s business school. Wolcott’s wife was extremely cordial and said she would tell her husband that I had called. I said that I would call back in a few days.

In College Station I looked up Dr. Robert Walker, A&M’s development officer. Hicks had talked at length about his long association with Walker, who was running the alumni association in 1970 when Hicks made his first matching gift to A&M. Walker remembered Hicks all right—he had even been fishing at Hicks’ farm in Franklin—but he didn’t remember anything about a $25,000 gift.

“Robert was a big dreamer,” Walker told me. “If he had worked as hard at something legitimate as he did on his schemes, he could have been very successful. The first time I knew Robert was up to something was when he asked if we would backdate a receipt so he could get credit with Gulf. I told him that would be unethical, a downright lie. Later he approached me about getting a bunch of guys together and giving the money to another person who would then get a matching grant. I said that would be downright illegal, to go somewhere else.”

I was getting a funny feeling in the pit of my stomach. Something was wrong here. Walker was telling me that Hicks never gave the $25,000, yet many of Robert’s friends remembered that big event—the donation, the luncheon in his honor, the plaque, and the room at the business school named for Hicks and Wolcott. I suggested that the donations might have been in the name of Jim Ed Wolcott and asked Walker to check his records. No, he told me after an assistant had checked the records, there had never been an endowment at A&M in the name of either Robert Hicks or Jim Ed Wolcott.

“Are you absolutely sure?”

“Positive,” Dr. Walker said. “It never happened.”

I walked across the A&M campus, trying to sort things out. I couldn’t believe that Hicks had lied about something so elementary, so easily checked. I remembered what he had said about blowing the lid off the college fundraising business, but the only thing this revelation blew was his own credibility. If he had lied to me about this, he had probably lied about everything. But why? What could he possibly gain from lying to me? I sat on a concrete bench under a large oak, watching the flow of students in designer jeans and pink gingham dresses and, only occasionally, high-gloss senior boots with spurs, thinking how things had changed in the fifteen years since Hicks had walked this same path. And yet the substance was still there, the pride and tradition, and the fear of things that hadn’t happened before. There had been a story in the paper that same day telling how the Supreme Court had ruled that A&M had to allow gays to organize on campus. Predictably, a lawyer for the Aggies had speculated that the next thing the court would require was sex with animals.

Now that I thought about it, it didn’t make sense that a school as well financed as A&M would allow itself to be involved in such a scam, and certainly not for $25,000. Still curious, I telephoned the woman Hicks dated from the fall of 1982 until his arrest the following spring. She was not pleased by the prospect of reviewing her friendship with Hicks, but she agreed to meet me at a bar near the A&M campus if I promised not to use her name.

She was a bright, attractive woman in her late twenties. Although it was apparent that Hicks had treated her wretchedly, she didn’t sound bitter. When Hicks was down, she recalled, she loaned him $3000 and allowed him to use her credit cards. When he was on the run, he called her from San Francisco and asked her to meet him there, but when she arrived she found him dating another woman. At the trial she testified that they had talked of marriage, but those plans had vanished. A few months after the trial, Hicks responded to her kindness by writing his attorney a letter accusing her of forging his signature on checks and of refusing to turn over $25,000 and other valuables that he said he had given her. The same day he wrote his attorney, he wrote to the woman, bluntly terminating their relationship with these words: “Please do not attempt to contact me in the future on this or any other matter.”

“Robert had this amazing capacity to get people, women in particular, to do anything he wanted,” she said, stirring her coffee. I thought she was going to cry, but then she got this half-smile on her face and said, “I’ve often wondered, if Robert rang my door bell at two a.m., as he did many times, what I would do. I’d probably open the door and let him in.”

A User

The next day I drove from College Station to Franklin, thinking about something else Robert’s ex-girlfriend had told me. Robert had a strong feeling that he was born at the wrong time, to the wrong parents, in the wrong place.

It was midday when I arrived, and except for the black man watering the Robertson County Courthouse lawn, the Franklin square was deserted. There was a drugstore, a newspaper office, a Western Auto, and a funeral home, but no sign of life, nothing stirring except the imperceptible particles of decay found in almost all small towns. Compared with Franklin, the A&M campus was Paris, France. It wasn’t difficult to understand how this milieu could affect a boy who had deep-seated feelings that he was born in the wrong place.

I found Robert’s mother in her office on the third floor of the courthouse. Marjorie Hicks was a pleasant, efficient, open woman, exactly the sort of woman you would expect to be a district clerk in a small county in Central Texas. I knew from conversations with Robert’s friends that he thought his mother had betrayed him by giving too much attention to her other sons, John Hicks and Fred Eden. The feeling of betrayal was one of Robert’s dominant emotions. He believed that he had been betrayed by his family, his friends, and his lawyers, which was curious because the evidence was overwhelming that the person who had done most of the betraying was Robert Hicks.

Marjorie Hicks took me to an unoccupied jury room; she told me that her son had written her only one letter since being sent to prison. It was foully worded and abusive. “It was the most insulting letter I ever read,” she said. “I thought about burning it, but I changed my mind.” After that, Robert broke off all communications with his family—all their letters and even Christmas presents have been returned unopened. “He sent word that if I die, he doesn’t want to know about it,” she said. I had imagined that Mrs. Hicks would be reluctant to talk about her son, but she was eager and pumped me for information on how he was doing. I told her that the last time we visited, Robert had started growing a beard. She shook her head in wonder. “He was always so independent,” she said. “When he was only eleven he subscribed to his own newspaper and had his own phone installed.”

Robert and his father just couldn’t get along when he was a teenager, and he moved across town to live with his maternal grandmother and a great aunt. People who knew Robert described him as a user. He had few close friends in school. He showed potential in track and football, but he quit sports and graduated ahead of his class by taking correspondence courses. Acquaintances remembered that he was always impatient and in a hurry. Later, at A&M, he took summer courses. Though Robert was nearly two years younger than John Hicks, he graduated from college a year ahead of his brother.

Friends outside Franklin got the strong impression that Robert was the core of the Hicks family, the patriarch. Talking to people in Franklin, I learned that nothing could have been farther from the truth. Persuading his half brother Fred to move from Houston and become his property manager hadn’t been an act of familial concern; it had been an act of cruelty. Fred, fourteen years older than Robert, had never paid him a lot of attention until the job came along. “He just wanted to show Fred who was boss,” a member of the family said. A sister in Dallas had talked to a friend who was a nurse and had come up with a term to describe Robert—“sociopath.”

The First National Bank in Franklin was one block over from the courthouse and one block up, on the highway to Hearne. John Hicks, who owned 20 per cent of the bank, wasn’t much older than Robert, but he looked it. He looked as though he had been born behind his desk. He was a deeply religious man, and his ambitions were directed inward. He confessed that he had never been able to understand his younger brother.

“Robert never took much interest in family affairs,” he told me. “He had no use for our dad’s farm, which our dad loved. When he would come around, our dad used to say, ‘I wonder what Robert wants now.’ Robert never came around unless he wanted something. Robert wanted respect, but he never learned that respect has to be earned.”

A few blocks down the Hearne Highway stood the auto supply store, now owned by Fred Eden. Fred had never bothered to take down the Hicks Auto Supply sign out front. A large, rumpled man, he chain-smoked as we talked in the stockroom of the store. In July 1982, after months of negotiations, Fred was surprised when Robert suddenly agreed to sell his inventory to Fred for $100,000. Later, when Robert was on his way to prison, Fred bought the building. Robert told me they got it for forty cents on the dollar, but Fred said Robert’s asking price was highly inflated.

“There was no way to tell what the business was worth,” Fred said. “Robert never kept books.”

A Dirty Secret

What sort of aberration was this? A business school graduate who didn’t keep books? A guy who hated his hometown yet couldn’t escape? A would-be philanthropist who wanted recognition so badly that he lied about a $25,000 donation to his old school? It occurred to me again as I was driving out of town that an awful lot of people seemed to remember the donation, the luncheon, and the plaque.

I knew that Hardgrove wasn’t lying, but I telephoned him again to see if he could supply additional information.

“Dr. Jarvis Miller was president of A&M at the time,” he said. “As a matter of fact, I think he attended the luncheon.”

I called Dr. Miller, certain that even if the luncheon had taken place, he wouldn’t remember it after all this time. On the contrary, he remembered it well. He described Robert Hicks exactly—“an attractive, nice-looking, extremely likable, and glib young man”—and added that when the publicity of Hicks’ arrest came up, he thought to himself that it sounded like the same young man. “Call Dr. Robert Walker at the Texas A&M Development Foundation,” he suggested. “He was the one who handled the gift.”

Walker had already denied that there had been any gift. But when I called again and told him about my conversation with Jarvis Miller, he said he would do some more checking. Later, he called back and said, “It seems they did have a luncheon. Hicks kept saying he was going to do something for the School of Business. But the plaque was for his membership in the Diamond Century Club of the Association of Former Students.”

We were right back where we started. I tried to call Jim Ed Wolcott again but got no answer. There wasn’t much need to talk to Wolcott anyway; I was positive by now that Hicks had made up the entire story. I was ready to give up the pursuit.

The next morning, however, an extraordinary thing happened. I was still asleep when the telephone rang. It was Dr. Walker again. “Well, I did some more checking,” he said, and I could hear the strain as he prepared for what he had to say. “It seems there was a luncheon, and a plaque was given to Robert on a twenty-five-thousand-dollar commitment to the management program at the business school. A small amount was actually given, and it was matched by Exxon.”

“You’re saying Robert really did make a donation?”

“A small one.”

“How small?”

“I don’t have the exact figures, but it was less than ten thousand dollars, counting the match.”

“So Exxon did make a matching grant?”

“That’s right.”

“What about Jim Ed Wolcott?”

“Yes, that name rings a bell. There was a plaque put up in what was called the Hicks-Wolcott room. It was taken down, of course, when Hicks was indicted. I guess that’s the reason people over there would rather forget about it.”

I sat on the edge of my bed, trying to absorb the full impact of this revelation. Someone had lied all right, but it hadn’t been Robert Hicks. They probably call it stonewalling over at the business school. What would Exxon do when it found out that A&M had unwittingly taken part in the fraud? What would poor Jim Ed Wolcott do? He had lived with his dirty secret for months, knowing that Hicks was in prison, knowing that his career with Exxon possibly hung on what Hicks might do and say. When I talked to Wolcott’s wife a few days earlier, I hadn’t really thought about the consequences of my questioning. I hated to think what had happened that night when Wolcott came home from work and learned that someone had been asking about Hicks and a $25,000 donation.

I called Wolcott’s number again and let it ring until a woman answered. It was his wife. When I identified myself, she became nearly hysterical. “I told you, we know nothing about that,” she said. “I don’t have time to talk. My husband is in the hospital with a serious heart attack.”

Instrument of Revenge

It’s funny how things turn out. During those several days when I was convinced that Hicks had lied, something happened. A window opened, and I looked in and saw the real Robert Hicks. He was like one of those optical illusions they used to run in the funny papers. You would stare at it and turn it upside down and stare some more, and if you kept looking long enough it flipped over and became something else. After that, every time you looked at it, you were surprised that you hadn’t seen it all along.

I had to reevaluate what I had learned about Robert Hicks, starting with the thick file of letters and documents he had given me. Once the window had opened and I saw the real Hicks, I read the documents again in a new light. What had seemed so mysterious and compelling now looked childish and transparent. Letters to FBI agents read like quasi-FBI reports. “I finally spoke with [the subject] at 2:45 p.m. The conversation lasted for approximately 15 minutes.” Almost every letter spoke of “coordinating our efforts.” A letter to an FBI agent in Honolulu boasted that “we [Hicks and FBI agents in Fort Worth] pretty well have all the loose ends wrapped up in this case.” The agents must have had a laugh or two reading correspondence from Hicks.

I also thought of a conversation I had had with Dr. Marihelen Kamp at her office at the School of Plant Sciences building on the Texas Tech campus. She was friendly and interested in helping Robert. Her relationship with Robert had nothing to do with her divorce from Dan Kamp, she said. When I asked her just what their relationship was, she explained, “I’m like a sister, a mother. I do things for him a wife would do, like planning parties and helping entertain.” She had repeated much of what she had written in her letter to Judge Hill—that Dan Kamp knew what Robert was doing and took part willingly. Thinking about it again, I realized that Marihelen Kamp was merely reciting the party line. She had bought Robert’s line, just like everyone else. She just didn’t know it was a line yet.

Looking at Robert in that new light, I saw something else. His need for revenge bordered on the sociopathic. He was being consumed by paranoia, vanity, and fits of self-destruction, and all he could think about was getting back at his imagined enemies. He had given seven names to the grand jury in Honolulu and added a couple more in his conversations with me. He hadn’t exhibited a glimmer of shame or guilt for his acts, and he was filled with contempt for the acts of others. I wasn’t sure if he really could comprehend the consequences. The investigation continues in Hawaii, and it is conceivable that the case will be reopened in Texas.

I no longer believed that any of the people he named had taken part in the scams. One or two may have been on the periphery in the beginning, when it still looked like a college prank, but none of them shared many of the spoils, much less contributed to the plot. Hicks contended that the payoffs were to come later, that his accomplices were in it for the long haul, but that theory was truly asinine; nobody except Robert ever believed there would be a long haul. I’m not saying he had a monopoly on greed or stupidity. There was plenty to go around. Like I said in the beginning, Robert wasn’t the only one who stood to profit. If the schools hadn’t been so greedy, so eager to look the other way and conduct arm’s-length transactions based upon sound business principles, none of this could have happened.

The question remaining was, Why did Robert hate these people enough to try to ruin their lives? Now I knew the answer. He believed they had betrayed him. That sounds trivial, childish, even irrational, but it sounds just like Robert Hicks.

I went down the list, filling in the motives. When his friend, Dan Kamp, took the witness stand, Robert thought he gave the impression they barely knew each other. Kamp didn’t deny that he had shared some of the ill-gotten money—all those trips were public record—but when the time came to share the blame, Kamp was nowhere around. Kamp had moved from his teaching job at A&M to the directorship of the Lubbock Parks and Recreation Department, while Robert had gone to prison.

Robert felt that James E. Scamardo, president of the United Bank in College Station, had betrayed him by foreclosing on what was supposed to be the future home of Robert Hicks’ empire.

In the case of his brother, John Hicks, and his half brother, Fred Eden, Robert’s thirst for revenge went back to a time long before any of them had ever heard of matching grants. They had gotten the respect Robert craved. That was manifested in many subtle ways and in some that were not so subtle. Several years after Robert’s father died, his mother arranged for Fred Eden to get one hundred acres of the family land. “I agreed,” John Hicks told me. “But Robert got viciously mad.” When Robert was arrested, John Hicks refused to lie for him and then refused to assume the note on the bank building in Hearne or to advise their mother to assume it. Fred ended up buying Robert’s auto parts store.

For each person there was some trivial or childish reason, some slight or slip that had been magnified many times in Robert’s mind and refocused as a pretext to cover the one thing Robert was incapable of admitting or understanding—that the only one to blame was himself.

Before making my final trip in May to the Federal Correctional Institution, I had lunch with Joe Hardgrove. We had talked frequently while I was checking out Robert’s story, so none of my conclusions came as a surprise. Joe had started looking at Robert in a new way too. Joe is a strong Christian and heavy into forgiveness, but he is no pushover. “Captain Invincible thought he was bulletproof,” Joe said. “I think he believed that you would portray him as America’s next antihero, tirelessly robbing the oil barons.”

Confronting Robert with what I knew to be the truth wasn’t easy. I still liked him. More than that, I had the same uneasy feeling I had experienced the first time we met, the feeling that he shouldn’t be here. He should be somewhere, but not here.

It was a hot, humid day, and we sat under a pecan tree in the recreation area outside the visitors’ room. I tried to phrase a general question about culpability. Didn’t it bother him knowing how many lives he had wrecked and how many more he had tried to wreck? Was there no trace of remorse? His expression was absolutely blank. I might as well have been talking to the ground.

Finally I said, “Look, here’s the bottom line. You’ve been conning me from the start. You’ve been using me as an instrument to get back at your enemies.”

Robert blinked, which with someone else might have been an admission of something but with Robert was merely a way of saying that he was way ahead of me. He had been twirling his mirrored aviator sunshades in his hands, but now he put them on and gave me his full charm smile, so radiant I wanted to look away. “Well, I don’t think that’s any big secret,” he said in his sweet voice. “I told you I was a con man.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- College Station