This article is co-published with ProPublica.

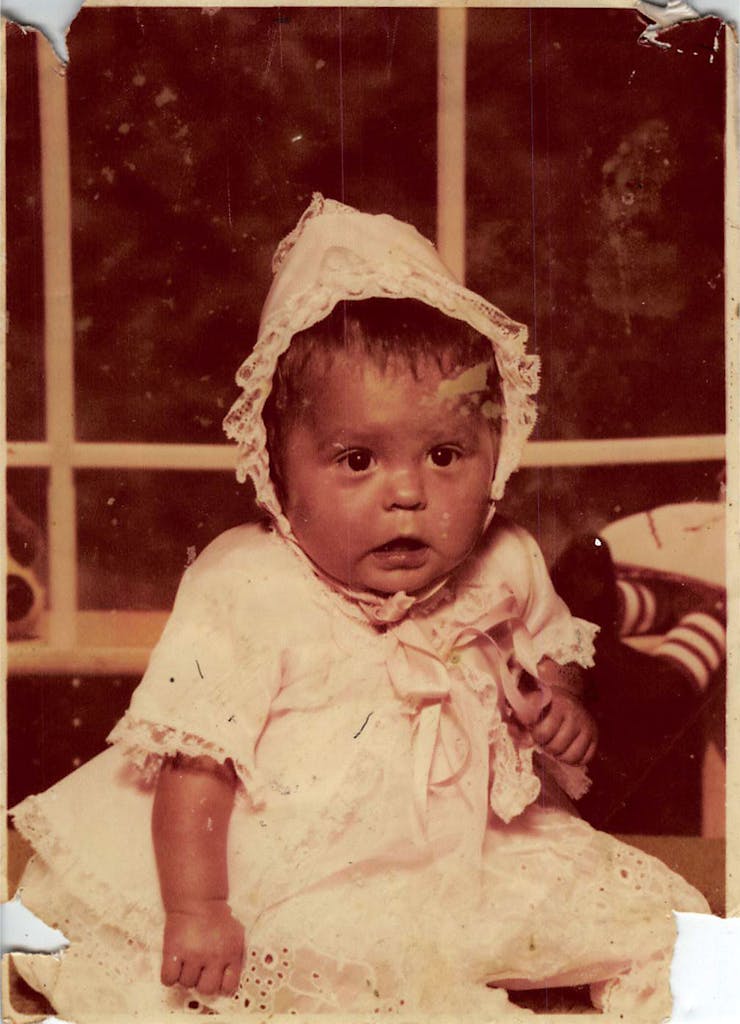

A San Antonio grand jury on Wednesday brought a second new murder charge against former nurse Genene Jones, advancing prosecutors’ campaign to keep the suspected serial killer of babies behind bars for the rest of her life. The indictment—in a case that dates back more than three decades—charges Jones with killing two-year-old Rosemary Vega, by injecting her with “a substance unknown.” In an interview this week, the child’s mother recalls watching Jones push a drug into her daughter’s IV line shortly before she went into cardiac arrest.

Jones, now 66, is suspected of killing more than a dozen infants in the pediatric intensive care unit at San Antonio’s charity hospital during the early 1980s. But she was never charged with any of those deaths at the time—partly because it was expected that she’d never leave prison after receiving a 99-year sentence for murdering a child in Kerrville, a nearby town. That assumption proved faulty. Thanks to a Texas law aimed at reducing prison overcrowding, it became clear a few years ago that the state would be forced to release Jones in March 2018, after she’d served about one-third of her sentence.

With that date fast approaching, San Antonio prosecutors last year launched a secret investigation to see if they could bring a new murder charge against Jones. It led to her May 25 indictment for murdering eleven-month-old Joshua Sawyer in December 1981 with a massive overdose of the anti-seizure drug Dilantin. That charge—paired with a $1 million appearance bond—seemed likely to keep Jones behind bars at least until her new trial, perhaps two years off.

But at the time, Bexar County District Attorney Nicolas “Nico” LaHood vowed to bring further charges. “My goal is not to leave one baby behind,” he declared. “In a perfect world, we believe she’d be held accountable for every baby we believe she stole from their families.”

Indeed, the grand jury that indicted Jones for the death of Joshua Sawyer last month also heard tearful testimony that same day from Rosemary Vega’s mother, Rosemary Cantu, in anticipation of today’s charges.

Jones has always insisted she was innocent of any crimes. A prison spokesman says she has instructed officials to decline requests for interviews. She has yet to receive a court-appointed lawyer.

Rosemary Vega was admitted to Bexar County Hospital on September 13, 1981 for a relatively routine “de-banding” operation, required to treat a congenital heart defect. Her mom, Cantu, was 18 at the time. She worked in the housekeeping department at Bexar County Hospital, where her duties included cleaning the rooms when children left the pediatric ICU. She knew Genene Jones.

Rosemary Vega was admitted to Bexar County Hospital on September 13, 1981 for a relatively routine “de-banding” operation, required to treat a congenital heart defect. Her mom, Cantu, was 18 at the time. She worked in the housekeeping department at Bexar County Hospital, where her duties included cleaning the rooms when children left the pediatric ICU. She knew Genene Jones.

According to a doctor’s detailed two-page “narrative report,” a pre-surgical physical examination of Vega found “an alert child, playing, and in no acute distress.” Dr. J. Kent Trinkle, a star cardiothoracic surgeon who later went on to perform San Antonio’s first heart transplant, operated on Rosemary. According to medical records, “the procedure went without difficulty.”

Rosemary was then taken to the pediatric ICU to recover, where Genene Jones worked. During the 3 to 11 p.m. shift, under Jones’ care, Rosemary began experiencing breathing problems, was placed on a respirator, and suffered seizures. At 2:15 a.m., a surgery resident noticed the breathing machine had been feeding her too little oxygen. “…Ventilator setting had been altered by unknown source,” the doctor’s narrative report noted.

After a difficult night, Rosemary “seemed to stabilize” throughout the next day, according to the doctor’s notes. Then, at 5:30 p.m.—again under Jones’ care—she suffered the first of three episodes of cardiac arrest resulting in severe, irreversible brain damage. She was pronounced dead at 7:52 p.m. on September 16, 1981. According to a later internal hospital review, “Nurse G. Jones was in attendance during the final events.”

In an interview, Rosemary Cantu told me she had watched Jones inject something into her daughter’s intravenous line shortly before her first arrest. “Everything was good,” said Cantu. “I was sitting by her bed after the surgery. Then Genene Jones came on in the afternoon, and that’s when it all happened.”

“She walked in with the injection,” recalls Cantu. “I saw her and asked her: ‘What was she doing? What are you going to give her?’ The [other] nurse had just left and took all Rosemary’s vital signs. She said, ‘I’m giving her something to help your baby rest.’ After she walked out, not two minutes later, my daughter started turning purple. The monitors went off; people started running. She was doing good until Genene injected her. Then she started getting the code blue.”

After so many episodes, Rosemary’s “neurologic status deteriorated to the point of being unresponsive to pain…” according to the doctor’s narrative. Recalls Cantu: “I had to make the choice, me and my husband, to let her go, because there was nothing more they could do.”

Cantu said she had planned to make a career at the Bexar County Hospital. “I liked working with babies,” she said. But a short time after burying her daughter, she quit. “I went back, tried it, and I couldn’t take it.” Cantu, now 54, has five surviving children and twenty grandchildren.

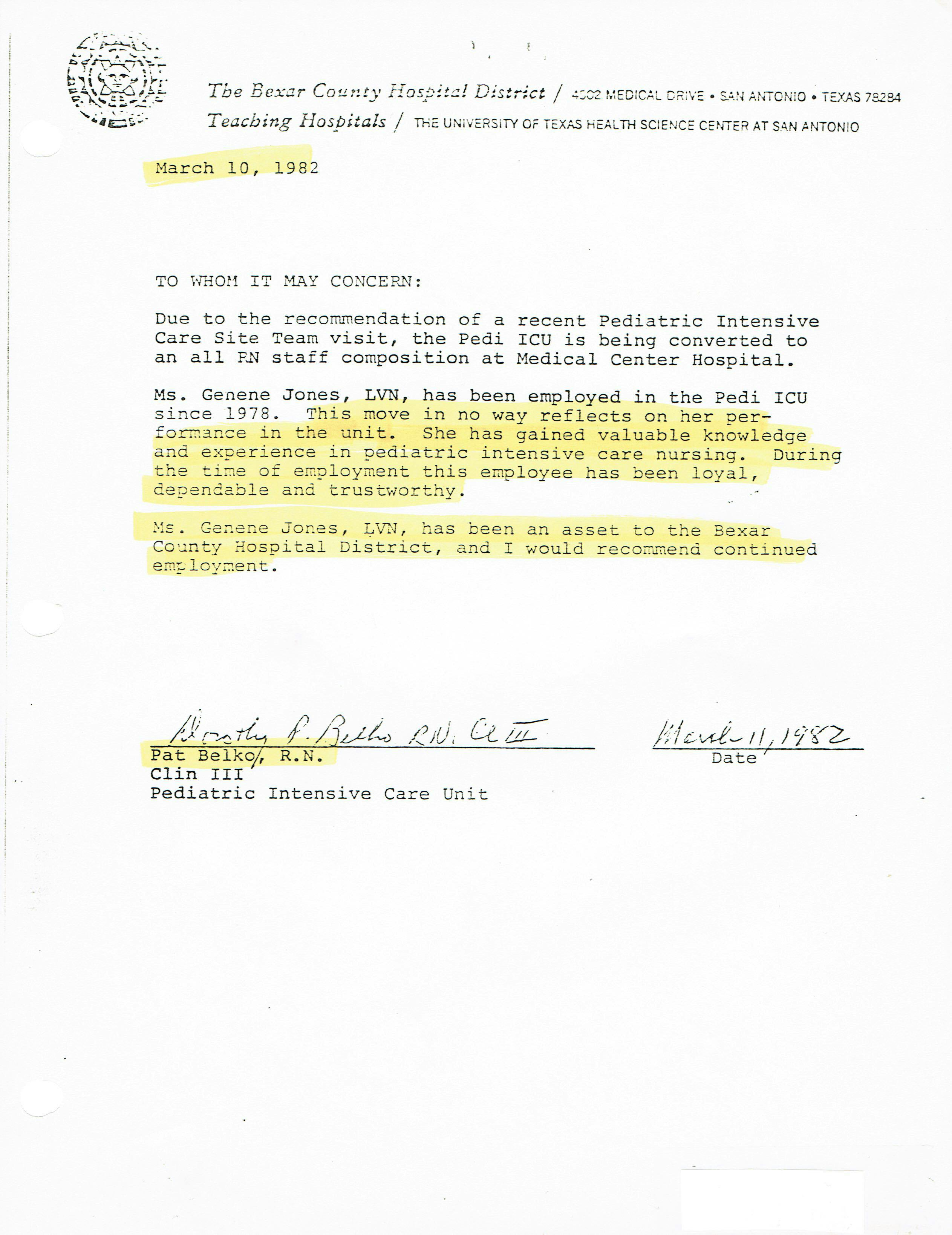

Rosemary Vega’s demise, along with other post-surgical deaths, surprised and infuriated Trinkle, who demanded that something be done about care in the ICU. Suspicions about Jones had been so widespread that other nurses had begun calling her hours on duty “the Death Shift.” After a secret internal investigation, the hospital ultimately handled the problem by removing Jones—along with the six other licensed vocational nurses—under the pretext of upgrading the ICU to an all-RN staff. All, including Jones, were given a good recommendation.

Jones went off to work in a pediatric clinic in Kerrville, where the death of a fifteen-month-old child named Chelsea Ann McClellan triggered criminal investigations in both Kerrville and San Antonio that generated international headlines. Jones was convicted of murder in the McClellan case and sentenced to 99 years; a two-year investigation in San Antonio resulted in only a single injury to a child charge, with a 60-year sentence, to run concurrently—but with the expectation that she’d spend the rest of her life behind bars.

The effort to bring new murder charges in San Antonio began in earnest last December, leading to the May 25 grand jury session that produced Jones’ indictment for the Sawyer murder. Rosemary Cantu was among three mothers who testified before the grand jury that day. Each left the grand-jury room in tears.

Left to deliberate on their own after prosecutors left the room, the grand jurors took less than two minutes to hand down the Sawyer indictment. They took less than five more minutes to set a $1 million appearance bond. As the grand jurors exited the courthouse meeting room, most of them were in tears, and they hugged the three waiting mothers.

After the Sawyer indictment, Larry DeHaven, the 70-year-old DA’s investigator who made the Jones case his personal crusade, delivered the news to Jones at the Texas state prison system’s Murray Unit in Gatesville. DeHaven says Jones was “real polite.” On hearing about the new murder charge, he recalls, “She teared up a little bit. I don’t think she was expecting it.”

The same grand jury panel indicted Jones on Wednesday for the murder of Rosemary Vega, setting a second $1 million appearance bond. “I’ve been waiting for this moment since my daughter passed away,” says Rosemary Cantu, in anticipation of today’s action. “It just hurts me that I waited so long before somebody would hear me.”

Peter Elkind is a former Texas Monthly staff writer and the author of The Death Shift: Nurse Genene Jones and the Texas Baby Murders.