Halfway between Anchorage and Seward, Alaska, riding shotgun in a rented Kia Rio, banking around a hairpin turn, the best bass fisherman in Texas waters is feeling a bit out of place and looking for something to hold on to.

“There have to be bass in there,” Keith Combs says, pointing left to a shallow tannic bog, ringed with lily pads and pencil reeds. On the right is a Pacific inlet called Turnagain Arm, which, with the tide out, presents as a long expanse of glacial mud. Water, water, everywhere, and not a bass to catch. In fact, there are none within hundreds of miles.

A largemouth was caught in Alaska in 2018, but it was likely an aquarium refugee, and it is widely acknowledged that Alaska is the only state without a population of America’s favorite—and most recreationally lucrative—freshwater sport fish. Even though Combs is here on a bucket-list angling trip, chasing monster halibut, then heading to Bristol Bay for trout and salmon, bass are his tether to the world, and to sanity. He gets a little twitchy if he goes a couple of days without catching any. Every year he visits Venice, Louisiana, to battle redfish, which are bigger, harder-fighting, and substantially tastier than bass. He looks forward to the trip, but after a day or two he’s ready to go home to Texas, to fish for bass, an all-consuming passion that he’s turned into a career.

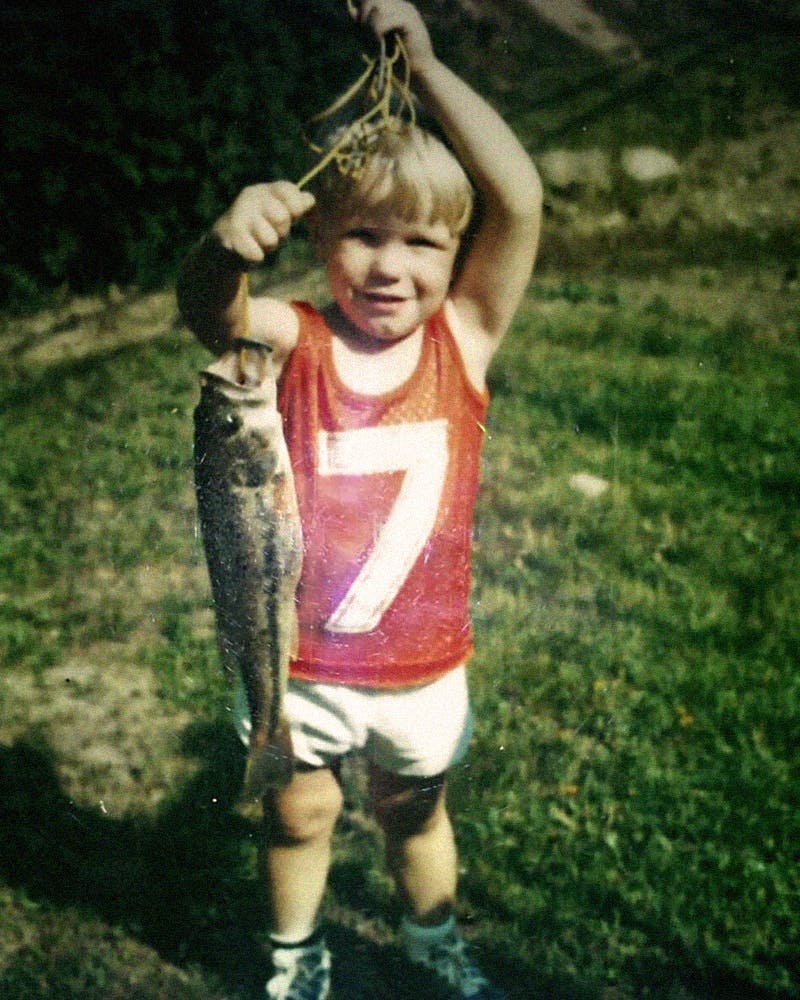

Combs, 44, grew up in Nolanville, halfway between Austin and Waco—and close by the bass-rich Belton and Stillhouse Hollow lakes. He now lives in Huntington, in East Texas, near lunker-filled Sam Rayburn Lake. He was born into the right state for his obsession. Like high school football, deer hunting, and barbecue, bass fishing may not be exclusive to Texas, but it’s done bigger here—and, some would say, better than anywhere else. Ten pounds is the line of demarcation for a true trophy in the Lone Star State, and there are more ten-pounders in any of several Texas impoundments than in whole states like Wyoming or Connecticut. Florida and Alabama have similar bass cultures and California’s the gateway to innovations from bass-crazed Japan, but only in Texas can you compete to win five figures or a boat just about every weekend. Some high school tournaments here turn out in excess of four hundred boats. It was no accident that Combs chose Sam Rayburn as his home lake. Not only is it closer to the nationwide tournament action than was his former home near Lake Amistad, the giant border impoundment near Del Rio, but Combs believes that Rayburn is “an iconic lake in bass fishing, an historic lake for people who are ate up with the sport.” It’s a practice field that produces champions.

“If you fish Texas, you’re a home run hitter, period,” says Michigan’s Mark Zona, host of Bassmasters and Zona’s Awesome Fishing Show. “Keith does not go fishing for a nibble. He goes to catch the biggest sumbitch that swims. He’s become deadly outside of the state as well, but he still lives by his roots.”

His dominance in tournaments within Texas is unparalleled, and he credits that to his upbringing in Nolanville: “Within a forty-five-minute drive we could fish lakes with grass, boat docks, super-clear water, dingy water, smallmouths, and largemouths . . . places where the fish stayed shallow all year and places where they stayed deep all year.” That variety of fishing terrain honed Combs’s skills and translated into a string of Toyota Texas Bass Classic victories (2011, 2013, 2014), along with wins in top-level events on Falcon Lake and Lake Tawakoni. During the 2014 Toyota event on Lake Fork, about eighty miles east of Dallas, his best five fish each day, added up over three days of competition, totaled 110 pounds—a world record for high-level competition. The average bass weighed in at more than seven pounds. He has won more than $2 million since 2001, the bulk of it since 2007. His biggest bass ever was a fourteen-pound hog that he hauled out of Falcon Lake in March of 2011. But for all his success, Combs, like most fishermen, obsesses over the ones that got away—especially on the biggest stages.

Combs has not yet won either of the sport’s top titles, the Bassmaster Classic (“the Super Bowl”) or Angler of the Year award (“the MVP”). Anglers and fans agree that you need to win one or both to become a Hall of Famer. “You never want to be Dan Marino, with the most passing yards without winning a Super Bowl,” Zona says. Combs has finished in the top 10 for Angler of the Year four times, including when he was runner-up in 2016, but in eight Classics the best he’s finished was ninth, also in 2016. “I’ve had the fish on my line to win the title more than once,” he says. “That eats at you. Everything has to go right.”

It’s difficult for an obsessive personality to compete in a sport where so many variables are unknowable and uncontrollable. If you want to become a superior free-throw shooter, your challenge is the same every time you step up to the line and your method can and should be identical on each shot. Tournament bass fishing is nothing like that. In 2017 Combs drove 2,300 miles round trip from his home in Huntington to Lake St. Clair, just north of Detroit, a little over a month before a tournament there. Once on the water, he never made a cast. He just idled his boat around the lake for four days, face buried in the electronic displays of his multiple fish-finding devices, which combine GPS readings with various forms of sonar. He was hunting for subtle differences in the lake bottom, such as isolated rock piles or edges in the underwater vegetation, that might help him in the event. Even if he found such “juice,” it might not matter. The fish could move by tournament time. They might simply not bite, for reasons known only to them. The weather could change. Another competitor could beat him to his best spot. Nevertheless, Combs crisscrossed the lake, back and forth, back and forth, marking waypoints, trying to find something that would put him in a positive frame of mind going into the competition.

When he got back home, he immediately mounted his tractor to mow the twenty acres where he and his wife, Jennifer, recently built their dream home. Back and forth. Back and forth. He used the time to think over what he learned at St. Clair. The countless hours alone aren’t new to him. “It’s the way I’ve always done it, going all the way back to when I had nothing. It worked for me, so I kept at it,” he says.

Though he’s been fishing most of his life, Combs came late to the pro game. In 2007, at age 31, he left his job at a machine shop in Temple to move to Del Rio and work as a fishing guide on the border lakes of Amistad and Falcon. When he dropped his clients back at the dock in the afternoon, he’d put his rods away and motor around the lakes watching his electronics until dark, looking for new subtleties beneath waterways he already knew intimately. He could’ve located the biggest school of fish on the lake, but he wanted to have backup areas for changing conditions.

“That’s one of his best characteristics,” says Jennifer. “There are other guys who get into a slump and . . . they’ve lost half the battle before they even hit the water. Whether Keith wins or doesn’t do well, as soon as he gets off the stage, it’s on to the next one. He puts it behind him.”

Zona recalls that Combs called him immediately after his record-setting Lake Fork victory. “You wouldn’t have even known he won,” Zona recalled. “The dude’s a flatline. In most sports, after that kind of performance, there’s a lot of epic self-back-patting. Keith is a hard-hat fisherman. When he scores, he hands the ball to the ref. When he fumbles, he owns it too.”

Combs’s success results from the same obsessive focus and continuous improvement that other elite competitors practice. Many other anglers on tour room together or travel in cliques and share information. Combs prefers staying alone; when he does have a roommate, he avoids clouding his instincts by conversing about fishing. On the Bassmaster website, the anglers’ profiles typically list hobbies such as golf, hunting, and spending time with family. For hobbies, Combs simply wrote: “I love fishing; it’s all I do.”

In six days of Alaskan fishing, Combs reeled in a hundred-pound halibut, caught all five species of Pacific salmon, and a number of rainbow trout. While these types of fishing might not be in his wheelhouse, his ability to read water and fish behavior was evident. Nevertheless, he itched to get home to his bass. After an all-night flight, he spent a couple of days meticulously organizing his tackle for back-to-back tournaments. He hopped in his Toyota Tundra and made the 1,650-mile drive to Waddington, New York, on the St. Lawrence River, for an event where he finished fourth out of 75 anglers, and won $15,000. Then he drove about 200 miles south to Cayuga Lake, in New York’s Finger Lakes, and came in twelfth, for a $10,000 payday.

Most anglers in either field would have gone home happy. Combs instead drove right back to the St. Lawrence, ostensibly to take some sponsors fishing, but really because he knows he’ll likely compete there again, and more time on the water was the best way to turn that fourth into the only thing that matters to him: a future win.

This article originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Hot Rod.” Subscribe today.