On the roadside billboards and church signs of the Panhandle, religion is sold chiefly as a form of encouragement, and when you get out on Interstate 27, it’s easy to see why. Heading north from Lubbock, you soon find yourself in what is sometimes referred to as the Big Nothing: thousands of square miles of featureless High Plains dotted with little towns whose very names—Friendship, Happy, Progress, Pep—seem to be a defense against the ominous feeling of being a lone body, without cover or companionship, in a place that big and flat; a feeling of being conspicuously vertical, like a prairie dog caught too far from his hole with a red-tailed hawk circling overhead. Over the past two years, few communities in this area have needed uplift more than the people of Tulia, who have seen their town, and all its secrets, exposed to the glaring spotlight of the national news media.

When I first visited Tulia on assignment for the Texas Observer, in the spring of 2000, little had been written about the previous summer’s now-famous drug busts. The story I came back with was a sort of perfect storm for drug-policy-reform advocates, neatly illustrating much that has gone wrong with the nation’s domestic drug war. Sheriff Larry Stewart of Tulia, a ranching and farming town of five thousand roughly halfway between Lubbock and Amarillo, had used grant money from the governor’s office to hire Tom Coleman, a gypsy cop with no experience in undercover work and, as it was later revealed, a checkered past. Coleman worked deep cover in Tulia for eighteen months with almost no supervision, during which time he reported making more than 130 drug buys, mostly small amounts of powdered cocaine, from 46 dealers. Although the deliveries were small, an unusually high percentage of them were alleged to have taken place near a school or a park, making them first-degree felonies.

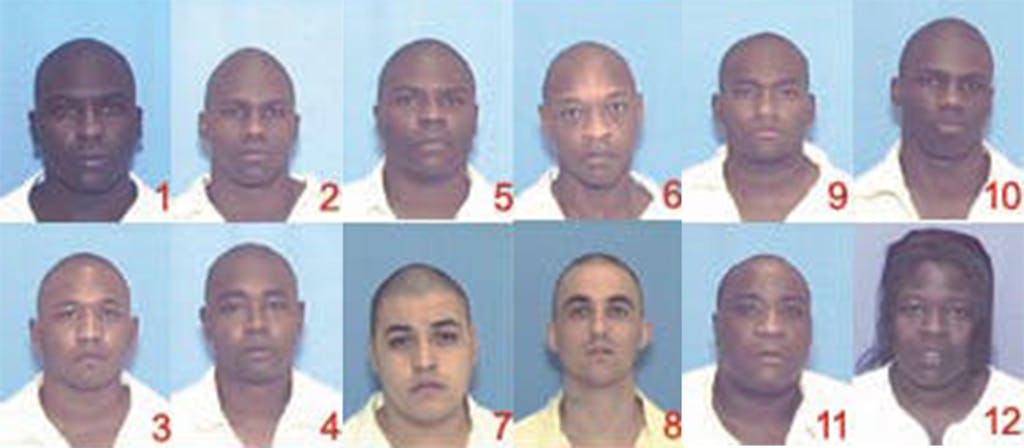

Coleman’s success seemed too good to be true, and it was. In not one single case did he wear a wire nor did anyone ever corroborate his claims with eyewitness or video evidence. When the arrests finally came, not one single suspect was found to be in possession of drugs. Perhaps most striking of all, 39 of the suspects were black in a town with fewer than 300 black residents. Few of the alleged dealers could afford to make bail. Several were known to be crack addicts, people who had neither the money nor the connections to acquire powdered cocaine. In a handful of the cases, Coleman botched the identification of his suspects so badly that the charges against them were quietly dismissed. None of that seemed to matter to the district attorney or to the juries that heard the first half a dozen cases, pronounced the defendants guilty, and handed down sentences of up to ninety years.

Defenders of civil liberties, particularly the William Moses Kunstler Fund for Racial Justice, in New York, and the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas, flogged the Observer story to everyone within range of a fax machine, and it gradually gained momentum; before long the New York Times re-reported it for page 1. Yet nothing concrete came of the publicity—almost none of the jailed defendants were released until they were paroled—and just as quickly the attention of the media and other interested parties dried up. Or it would have had it not been for a series of columns this summer by Bob Herbert of the Times, whose better-late-than-never outrage resuscitated the controversy. Suddenly, two years later, the black residents of Tulia are once again being asked to give interviews to the broadcast and print media, and so are the local authorities, particularly Stewart and district attorney Terry McEachern, who have learned by now to let someone else answer the phone. And the wheels of state government have finally begun to turn: Shortly after Herbert’s sixth column on the subject, Texas attorney general John Cornyn—in a hotly contested campaign for a U.S. Senate seat against, it should be noted, an African American—finally announced that he would support a state investigation into the Tulia arrests. (He had been begged to investigate for more than a year.)

It was a good time, I decided, to return to Tulia. So in September, I made another trip up I-27 to check in on the people I had interviewed on my first visit and to see how the town had survived its newfound notoriety.

Since I last interviewed him, in May 2000, Joe Moore has had a lot of time to think about what happened in Tulia and why. Moore, who was accused of delivering about $400 worth of cocaine to Coleman, was the first to go before a jury, and his trial set the pattern for what was to follow. The state began its case one day at nine o’clock, presenting a baggie of cocaine as its sole piece of evidence and Coleman as its only witness. Moore’s court-appointed lawyer called no witnesses. At noon the next day, he was sent away for ninety years.

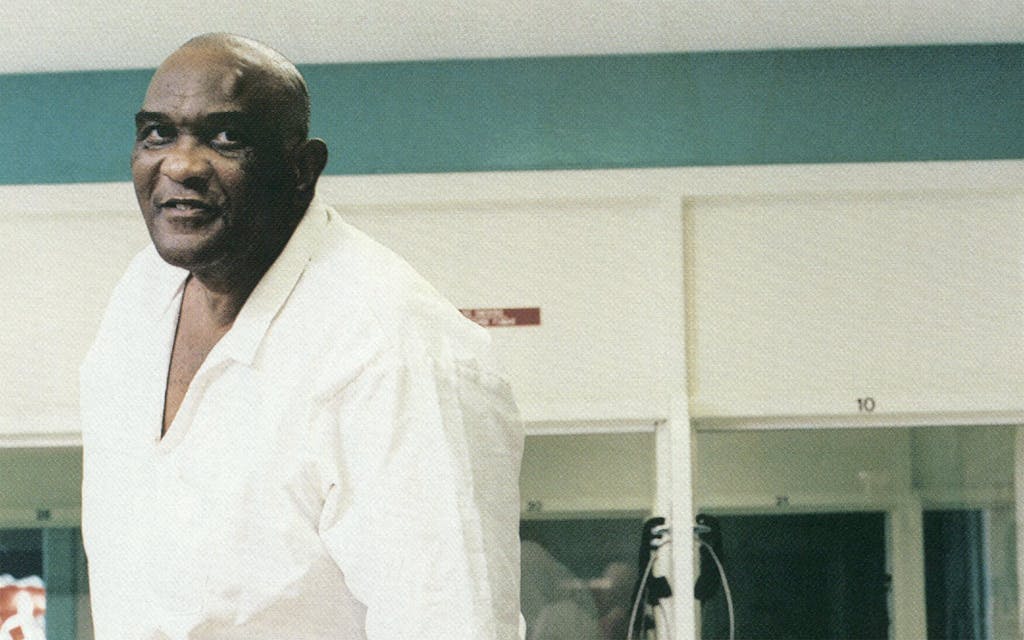

If you ask Moore how this came to pass, he will begin with a short history of black Tulia. Much of that story—as the 59-year-old related it to me from a visitation booth in Abilene’s Robertson Unit, where he is beginning his fourth year of incarceration—is about sheriffs and highway projects. When he first came to Tulia, in the fifties, the sheriff was a man named Darrell Smith. At that time, the black community was on the north side of town, and Smith used to drive through it almost every Friday and Saturday night. “His main thing was, he wanted us people to go to bed at twelve. He’d drive down there and if he didn’t see any lights, he’d like to kick the door down.” Moore laughed as he said this, showing the five teeth he has left in his giant head, one of them capped by the prison dentist in stainless steel. For all his toughness, Moore continued, Sheriff Smith was honest, and people respected him.

Later, when U.S. 87 was extended into Tulia from the north, the highway department bought everyone out, and the black residents were encouraged—with promises of free running water—to relocate to the northwest side, west of the railroad tracks, in an area that came to be known as the Flats. John Gayler was the sheriff then, a fair man with a live-and-let-live philosophy. “As long as you didn’t come across the tracks,” Moore told me, “Gayler wasn’t gonna mess with you.”

Those were good days for Moore, who quit the backbreaking work of loading hay and opened a little juke joint stocked with bootleg beer bought in Nazareth, the nearest wet town. Not only blacks but also white businessmen and ranchers, in town for the cattle auction held every Monday, would stop in to drink and gamble, and Moore was selling one hundred cases of beer a week. “Nobody messed with me. My place was wide open,” Moore said. He became known as the mayor of Sunset Addition, as whites called the neighborhood. Blacks just called him Bootie-Wootie.

In the late eighties a new highway—an expansion this time of I-27—was slated to be built, meaning anywhere from thirty to one hundred shacks in the Flats had to go. “They broke their deal with us,” Moore said. Meanwhile, a new sheriff, Paul Scarborough, and his deputy, Larry Stewart, had taken office, and Moore says, they had a different view of his business. They began to arrest him, something Sheriff Gayler had rarely done (Stewart denies that this represented a change in policy). Moore went to prison for possession of cocaine in 1990. He did just three months, but while he was inside, his joint was pushed down. When he got out, Moore turned to raising hogs, leaving the hustling life behind. “That was my life: rattlesnakes, hogs, and calves,” he said. Until Tom Coleman came to town.

Moore’s chronology throws Tulia’s fixation with drugs into a new light. Beginning with a few arrests in the mid-nineties, building momentum with a school drug-testing policy passed in 1996, and culminating in the big busts of 1999, the drug war in Tulia coincided roughly with the razing of the Flats and the black community’s move across the tracks—essentially pushing black and white Tulia into the same space for the first time ever. Of course, the timing also corresponded with the arrival of crack in the tiny towns of the Panhandle but not with the arrival of drugs per se; Tulians black and white had always had access to them, though perhaps not in proportion to their counterparts in the bigger cities. So why now, and why black Tulia?

“Propaganda is a funny animal,” said Gary O. Gardner, a farmer who lives in the nearby village of Vigo Park. Few reporters on the Tulia beat have filed their stories without a visit to Gardner’s compound, where he holds court from a converted pool room piled high with transcripts, writs, and affidavits, along with the occasional box of ammo. If Moore is the mayor of black Tulia, then Gardner, who is white and hails from one of the area’s original farming clans, is the mayor of rural Swisher County. Critical of the busts from early on, he has now made it his personal crusade to get Moore and the others out of prison. He blames politicians like McEachern for creating the atmosphere in which the busts could happen. “If you’re gonna make your living off the backs of somebody that you want to convict, you have to make ’em the enemy,” he said. “And in Tulia, everything is blamed on the black drug dealers.”

That kind of sentiment, repeated in essence on newsstands and in living rooms across the country, has hit white Tulia hard. Almost every week a letter appears in the Lubbock or Amarillo paper from an aggrieved Tulian, protesting the treatment the good people of the town have received. “I feel we have been persecuted, but it doesn’t really surprise us because we know what the media can do to a town,” said Glenna Reynolds, one of the letter writers. Recent revelations have not dissuaded Reynolds, who doesn’t fully support Coleman but does believe that most, if not all, of the defendants were guilty, possibly including Tonya White, who proved that she was in Oklahoma at the time of the alleged drug deal. “I just know her potential for being involved in drugs,” Reynolds said. She did concede that at one point she thought some of the sentences were longer than they should have been—she does not now—and she hopes people are getting rehab in prison. More than anything, though, she’s ready for it to be over. “I just wish they would allow us to heal and work our way through this thing,” she said.

Thelma Mae Johnson, Joe Moore’s longtime girlfriend and the leader, along with an Anglo minister named Alan Bean, of the local opposition to the busts, wants this to be over too—but only if it ends with everyone’s release. She has little sympathy for those who feel the town has been vilified. “When it comes to saying we’ve shamed our community by bringing the media here, I would say that when this bust came down and you paraded those people in front of the cameras and said, ‘Look, it’s the biggest drug bust in Texas!’—it would seem to me that’s what put Tulia on the map.”

What became of the other players in the sting? Officer Coleman—presented with an Outstanding Lawman of the Year award by Cornyn following the busts—has since been fired from two narcotics postings and has gone to ground in Waxahachie; his lawyer deflects the media inquiries that still regularly come, from Court TV to the London Independent. Thirteen of the defendants are still in prison and serving long sentences, despite the fact that the state legislature passed several reforms in 2001 in response to what one member termed the Tulia fiasco; a team of attorneys, led by Jeff Blackburn, of Amarillo, and Vanita Gupta, of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in Washington, D.C., has taken up their cases. The governor’s office has reorganized the grant program that funded the operation, putting agents like Coleman under the supervision of the Texas Department of Public Safety. An FBI investigation announced two years ago seems to have petered out. Local authorities, for their part, have refused to condemn McEachern and Stewart’s handling of the cases or to call for the release of those still incarcerated. “The lesson in all of this is that there is no political benefit to ruling for these defendants, and the judges saw that clearly,” one defense attorney said. “They asked themselves, ‘Am I going to give up my career for these people?’ And the answer was ‘No.'” Or as one person in the black community put it, more succinctly, “There are a lot of good, honest people in this community. They just don’t have any balls.”

Paul Holloway found that out the hard way. An attorney in nearby Plainview, Holloway took on several of the cases in the original sting as a court-appointed attorney, and it was he who discovered much of Coleman’s personal and professional history. The son of a well-known Texas Ranger, Coleman had, as deputy, skipped town on two different sheriff’s offices over the past five years; in Cochran County, he also left $7,000 in unpaid bills. In interviews and documents collected by Holloway and other defense attorneys, former co-workers and associates of Coleman’s in both towns referred to him as a pathological liar and a paranoid gun nut. Cochran County’s sheriff filed charges against him in an effort to collect restitution and placed a letter in his official file warning future employers not to hire him in law enforcement. Deep cover in Tulia was apparently his last chance to make good. Sheriff Stewart discovered the Cochran County warrant about six months into Coleman’s tenure but decided to continue the undercover operation anyway. (Stewart would not be interviewed for this story.)

Holloway packaged up what he thought he had found and presented it to district judge Ed Self. He asked for money for expert witnesses, though he figured he wouldn’t need them. “I thought that if somebody knew about Tom, it would all be stopped,” Holloway said. Instead, Self sealed the information Holloway had spent weeks collecting and denied his request. “Do you know what this means, Judge?” Holloway asked to no avail.

“My kid is twelve years old,” Holloway told me as we rolled through the wide, quiet streets of Plainview in his gold Mercedes, “and we just watched To Kill a Mockingbird. I told him the difference between me and Atticus Finch is this: At the end of the trial—this complete railroading of an innocent man—Atticus turned to his client immediately and said, “Don’t worry. We’re going to appeal.'” But Holloway’s grasp of reality would not allow him to do that in Tulia. “I took an oath as a lawyer not to disgrace this system, but I knew in my heart they would win no appeals. If this will be stopped, it will be when the prosecutor puts a stop to it.”

That’s not likely to happen any time soon. McEachern, who was pressured last summer to drop the two remaining cases from the sting, said he could not talk to me for this story either, citing pending appeals and a Department of Justice investigation, which, depending on whom you ask, is or is not still ongoing. “I wish I could tell you my side, because you’d hear a completely different story,” he said. Asked if he still stood by Coleman after the dismissed cases, the troubling revelations about his past, and his disastrous record since leaving Tulia, McEachern did not answer directly. “I’ll stand by what ninety-six jurors have found,” he said. “I’ll always stand by them.”

And so far, the white citizens of Tulia have stood by him. The New York Times doesn’t carry much weight in this town. If anything has put a dent in the picture McEachern painted for them of the drug problem here, it might have been another spectacular bust, one that barely made the papers but which everyone in town knew about shortly after it occurred. In June 2000, as the Observer story was going to press, a white teenager in Tulia told authorities that an older man had offered him cocaine in exchange for sex. The accusation became a jaw-dropper when the boy revealed the man’s name: It was Charles Sturgess, one of the owners of the Tulia Livestock Auction. Tulia is built around that cattle auction, and Sturgess was one of the biggest wheels in town. Sheriff Stewart, who went to church with the Sturgess family and bought cows from Charles, asked the local Texas Ranger to conduct the investigation. The Ranger wired the boy and sent him back out to meet with Sturgess, who made the same proposition once again as they cruised slowly through a pasture that night in his truck. The Ranger swept in and arrested Sturgess, but the most important revelation was yet to come: A search of the truck yielded three and a half ounces of powdered cocaine. In one single bust of a prominent white man—and a completely fortuitous one at that—many times more cocaine had been seized than in any single buy during Coleman’s entire eighteen-month undercover operation.

That much cocaine is more than one person can use. How many kids did Sturgess give cocaine to? Tulia will never know the answer to that question. A few months after he bailed himself out of jail, Sturgess drove his truck out to a piece of deserted ranch property and shot himself dead.

Nobody told Joe Moore about Sturgess’ death. When I gave him the news, he was amazed by every detail—except for the cocaine. Moore has lived in Tulia longer than most; he worked for Sturgess on occasion, just as he had for Sturgess’ father. “I been around hustlin’ and gamblin’ all my life,” he said. “I know what someone looks like when they’ve been using something.” Moore also knew what a cop looked like, which is why, he said, he warned everyone he knew to stay away from Coleman when he came to town, and why he says he ran Coleman off his property when he came by to ask for dope.

Nonetheless, Moore will spend his sixtieth birthday, this January, in all likelihood where he has spent his last three—in prison in Abilene. His health has not been good. Prison doctors had him on the wrong medication for diabetes for months, and the concrete and steel is hard on his back and knees, which are battered from a lifetime of hard work. But he eagerly examines the updates his defenders send him every month and keeps a careful eye on his parole date. “I’m gonna make it,” he told me. “I’m gonna make sure I make it.”

Nate Blakeslee is the editor of the Texas Observer.