Update, April 8, 2024: On April 4, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the U.S. Maritime Administration’s decision to issue a license for the SPOT terminal. In an email, Sierra Club attorney Devorah Ancel wrote that the petitioners are weighing their options.

When Texans think about what they might find in the Gulf of Mexico, whales aren’t usually top of mind. Unlike other large marine fauna, such as dolphins and sea turtles, whales are rarely seen from Texas beaches. One reason might be our gentle seafloor slope, which puts deepwater habitats farther from land than they are in many regions of the Atlantic and Pacific. But the massive cetaceans are out there. As many as twenty species swim in our local sea. Most common are melon-headed whales, pilot whales, and sperm whales. Leaping pods of orcas occasionally thrill fishing parties off the coast of Galveston.

Still, it’s a wonder that in one of the world’s busiest bodies of water, a species of whale larger than a school bus remained unknown to science until 2021. That’s when experts studied genetic and anatomic data from a whale that washed up in Florida. They reclassified it from a Bryde’s whale, a species that’s fairly common around the globe, to a new species called a Rice’s whale.

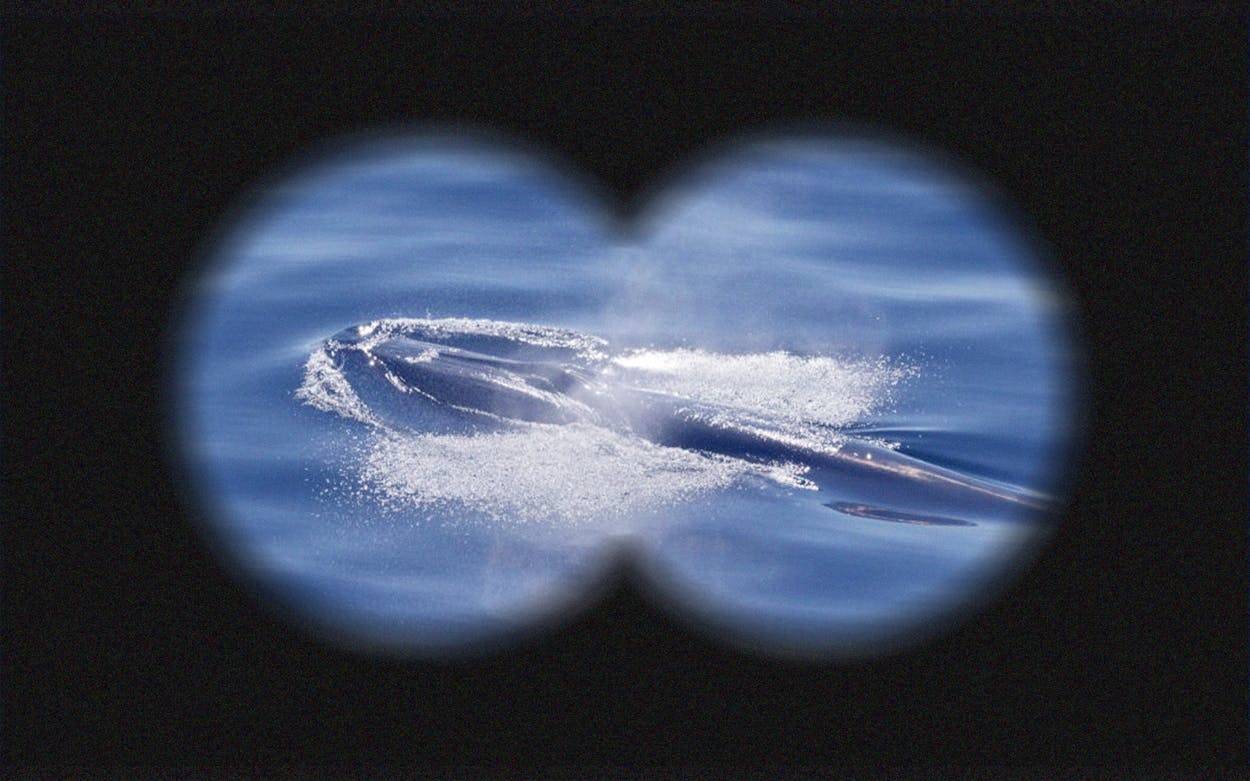

Some of the whale’s obscurity might be due to its shy temperament. “They’re not exuberant animals,” said Jeremy Kiszka, a whale biologist from Florida International University. “They are discreet.” And that’s not easy for an animal that can weigh 60,000 pounds and measure 41 feet in length. It’s the Gulf of Mexico’s only resident baleen whale, meaning it uses bristly keratin plates (not teeth) inside its mouth to filter seawater for food, including small fish and invertebrates.

Just as soon as Rice’s whales were identified, they became among the most endangered species in the world, with an estimated population of about fifty individuals. The new designation created an urgency to learn as much about them as possible as fast as possible. One way scientists do this is by listening to their distinctive vocalizations with underwater microphones.

In 2016 and 2017, a team led by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist Melissa Soldevilla moored a set of six waterproof recording devices on the seafloor along the continental shelf between Florida and Texas and listened to the sounds of the sea for about a year. Two were placed in the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, about a hundred miles offshore from Galveston. These hydrophones were part of a larger study designed to find out where the species now known as the Rice’s whale lives.

Working in the creature’s core habitat in the De Soto Canyon near the undersea border between Alabama and Florida in 2015 and again from 2018 to 2019, Soldevilla’s team matched recordings with sightings of the whales and identified a distinct repertoire of haunting vocalizations. Long moan calls were the most frequent. On a spectrogram, the sounds look like a sledding hill. Long moans would sometimes be followed by a set of three- to four-second pulses called a tonal sequence. Some sounds started at a relatively high pitch, fell rapidly in just a second, and were repeated dozens of times in a sequence. These patterns are unique to the Rice’s whale, allowing Soldevilla to conclude that the species—previously thought to range near the De Soto Canyon—is also a regular visitor to Texas. Follow-up recordings off Corpus Christi, where what we now know to be a Rice’s whale was sighted in 2017, further confirmed the leviathan’s presence in the waters off the Lone Star State. On July 24, fishermen captured video of what looked like a Rice’s whale about a hundred miles south of Galveston, in waters they estimated to be about five hundred feet deep. “The discovery that Rice’s whales persistently occupy the shelf-break waters of the northwestern Gulf of Mexico is exciting,” Soldevilla wrote in an email. “A broader habitat . . . improves their chances of survival.”

Soldevilla and her team also learned about the animal’s behavior. They did this by attaching an instrument-laden suction cup just behind the dorsal fin of a Rice’s whale. It remained in place for almost three days. At night, the whale took shallow dives and mostly stayed within 50 feet of the surface. But when the sun rose, it dove 750 feet or more to the continental shelf, about forty times a day. The tag revealed behaviors, called lunges, typical of whales accelerating toward a school of prey, engulfing a massive volume of water and food, and then sieving the water out through the fibrous baleen. But what was it consuming?

Using the hypothesis “you are what you eat,” Kiszka and his colleagues took small biopsies from the skin of some Rice’s whales and analyzed the carbon and nitrogen isotopes. These variants of elements are naturally found in the environment and can act as biological tracers showing what kind of foods an animal’s been chowing on.

The most abundant prey near that part of the seafloor, by far, was a two-inch- long fish called an Atlantic pearlside. But surprisingly, the isotopes revealed that Rice’s whales targeted a different meal: the nine-inch-long silver-rag driftfish, which is much less common. Caloric measurements explained why. On a calories-per-gram basis, the silver-rag driftfish was the most energy-dense of all potential prey. That’s probably critical to supporting the energy demands of a deep-diving whale.“They really go for quality, not for quantity,” said Kiszka.

Such energy-rich dietary demands could also make Rice’s whales vulnerable, Kiszka cautioned. Examples from species including dolphins in the Mediterranean and orcas in the Pacific Northwest show how cetaceans can become threatened when prey populations shift, as they have more often in recent decades as the oceans warm.

The Rice’s whale faces graver threats from humans, however, than it does from being a picky eater. These hazards include ship collisions, fishing-gear entanglements, industrial noise (from both ship traffic and oil-drilling operations) that interferes with whale communication, and oil spills. Notably, the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010 claimed 22 percent of the whale’s already diminished population, according to the final assessment of the Deepwater Horizon Natural Resource Damage Assessment Trustee Council.

Some of these threats may soon get bigger, says a petition filed in January by a coalition of environmental and citizen groups. At issue is the decision by the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) to approve the proposed development of a two-million-barrel-a-day export facility called the Sea Port Oil Terminal (SPOT) by a midstream energy company called Enterprise Products Partners. (Disclosure: Texas Monthly’s chairman is Randa Duncan Williams, who is also chairman of the general partner of Enterprise Products Partners.)

The proposed operations would pipe oil to a fixed platform where tankers could be filled about 35 miles offshore from Freeport, Texas—an area that the environmental coalition contends is part of the habitat of the Rice’s whale. The coalition’s opening court brief, filed in May, argues that MARAD didn’t adequately consider the potential effects on the Rice’s whale of additional noise from ship traffic, ship-strike threats, and oil spill risks, and therefore violated the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Deepwater Port Act.

A July 17 response filed by Enterprise Products claims that the terminal will decrease ship traffic and thus potential strikes to marine life because tankers too large to be loaded in port can be filled directly from pipelines, unlike the current system in which smaller ships ferry the oil, a process known as reverse lightering. It adds that the project design, with isolatable sections and emergency shutdown valves, mitigates damage from oil spills. This brief also cites the findings of the federal government’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), which they point out is extensive at nearly nine hundred pages and incorporates tens of thousands of comments. It states that “the [Rice’s] whale’s occurrence in the western Gulf near the SPOT project would be ‘extremely unlikely’ and ‘quite rare,’ because the whale’s core distribution area would still be ‘in water depths ranging from’ 300 to 1300 feet, whereas the SPOT port will be in 115-foot waters.”

Environmentalists disagree. “Federal action hasn’t taken into account the new, broader habitat in which this species is known to exist,” said Sierra Club attorney Devorah Ancel, who represents the petitioners. She pointed out there’s precedent for prioritizing whales’ protection. For example, regulations regarding ship speeds have helped protect endangered North Atlantic right whales on the East Coast. Similar measures might help here, she said. “But the point is, [federal agencies] haven’t chosen to apply those same mitigation standards in known habitat [of the Rice’s whale] in the northern and western Gulf of Mexico,” Ancel said. It’s possible this may change. At the end of July, National Marine Fisheries proposed expanding the Rice’s whales’ recognized habitat to include some of this region, although at deeper depths than where the SPOT terminal would be located.

If that habitat-expansion proposal were to be adopted, it would be months from now. In the meantime, the lawsuit will continue to wend its way slowly through the legal system. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals will eventually hear oral arguments. MARAD did not reply to Texas Monthly‘s requests for interviews. Spokespersons for Enterprise Products, the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division, and the Coast Guard declined to comment.

The story of the Rice’s whale will continue to unfold both in the sea and in the courts. And Texans are now an integral part of the future of a neighbor we’ve only just begun to know.

- More About:

- Critters