What follows is a eulogy delivered by Texas Monthly Executive Editor Skip Hollandsworth upon the death of his longtime friend, Alan Peppard.

When Alan Peppard was a kid growing up on Stefani Drive in Preston Hollow, he had this idea that he was going to be a rock star. He took some guitar lessons at the Melody Shop—and he and a few classmates from his school, Greenhill, formed a band that they named Five Card Stud, a curious nomenclature considering that they were the least studly group of teenage boys ever assembled. Alan did much of the lead singing. When the band performed at parties, kids would stand around the stage and stare at Alan in disbelief as he leaned into the microphone to sing Elvis Presley’s “Blue Suede Shoes.”

“You know, Alan,” one of his friends said. “You’re pretty good at talking. Have you ever thought about sticking with that?”

Alan did love to talk. Even as a teenager, he was a world-class storyteller. He would sit in the cafeteria at lunch and hold court on everything from the Kennedy assassination to the plot twists in the latest James Bond movie to the latest inside scoop on who was making out with whom behind the Greenhill water tower.

He was full of confidence, incredibly at ease around adults. When he talked to his high school teachers, he called them by their first names.

He was accepted into Southern Methodist University, where he decided to major in political science, but on a lark he took one journalism course from the famous professor David McHam. Alan, in all honesty, was not a deeply devoted student. He nearly flunked the class. But like so many people who met Alan, McHam was enchanted by him. He saw a talent in him. And of all McHam’s students, he recommended Alan to be an intern at D Magazine.

That’s where I was working in 1984 when Alan arrived at the D Magazine parking lot in a red Jaguar given to him by his father Vernon, a swashbuckling geologist and pilot who owned a successful oilfield mapping company.

Alan was wearing an Izod shirt—back then, Alan was simply crazed about Izod; he considered it the Texas man’s Chanel—and he was wearing khaki pants and topsiders without socks.

“Hello, I’m Alan Peppard,” he said, as cheerful as Bertie Wooster from the P.G. Wodehouse novels.

We all stared at him, utterly confused. We thought his last name was pronounced Pe-PARD.

Laura Jacobus, D’s feisty managing editor, cut him no slack. She had him start out fact-checking restaurant listings. Incredibly, he didn’t utter one word of complaint. He seemed to enjoy talking to the restaurant owners, asking them all sorts of questions—not about their food but about their clientele. Were any of them well known? If so, what were they like? What did they talk about when they were eating? Well, listen, maybe I can drop by sometime and have you fix me a drink and show me around.

Soon, he began writing stories—about such subjects as the kinds of cars Dallas celebrities drive. We kept staring at him in bewilderment. Why, we asked, would a young man from such a privileged life want to live the life of a hack writer? Why didn’t he go work for his father?

As it turned out, we weren’t the only ones intrigued by Alan. In 1987, when he was just 24 years old, the Dallas Morning News hired him “to cover social events in the Dallas area.”

Apparently, the man who hired Alan, editor Burl Osborne, assumed Alan would follow the tradition of past society columnists and trail after our city’s socialites, pleasantly chronicling their charity balls and best-dressed luncheons.

Well, not quite.

Let me take you back to September 30, 1987, Alan’s debut column:

“Today” section, page 3C.

Headline: PERENNIAL BACHELOR HAS A CHANGE OF HEART

Dallas oilman and perennial bachelor Bill Brosseau, the man who swore he’d never marry again, took the plunge Saturday night in San Antonio. Brosseau met 24-year-old Teresa Lucas (last year’s Miss Oklahoma) a year ago but hadn’t seen her again until three weeks ago when he and pal Matt Fleeger stopped for a drink at On The Border on Knox. And there she was. “We’ve been together every day since then,” says Brosseau. The couple went to San Antonio last weekend so Bill could check on an oil well he was drilling. “The well was successful,” he adds. On Friday night, Bill asked Teresa what she wanted to do on Saturday. “Well, honey, I wanna get married,” she replied. And so they did.

Let’s do a brief literary textual analysis of this item. None of us had any idea who Bill Brosseau was. He wasn’t from any of Dallas’ old-money families. He had never before appeared in a column written by Nancy Smith or Julia Sweeney.

But for Alan, none of that mattered. What he wanted to do was celebrate a cast of Dallas characters whom we had no idea existed.

Yes, Alan wrote about the money raised at the Crystal Charity Ball. But he also wrote about the raucous Dallas Margarita Ball held at a DFW airport hotel.

Yes, he wrote about the great established families of Dallas—the Hunts and the Hills and the Hamons and the Dedmans.

But he also loved the new money that had come to town—the Joneses and the Schlegels and a Midland oilman named Bob Franklin, who had bought a townhouse and turned the third floor into a disco.

Alan wrote about everything from the mansion that Tony Romo had purchased in the suburbs, to the comings and goings of Jessica Simpson, to the antics of Bobby Goldstein, creator of the Dallas-based Cheaters TV show.

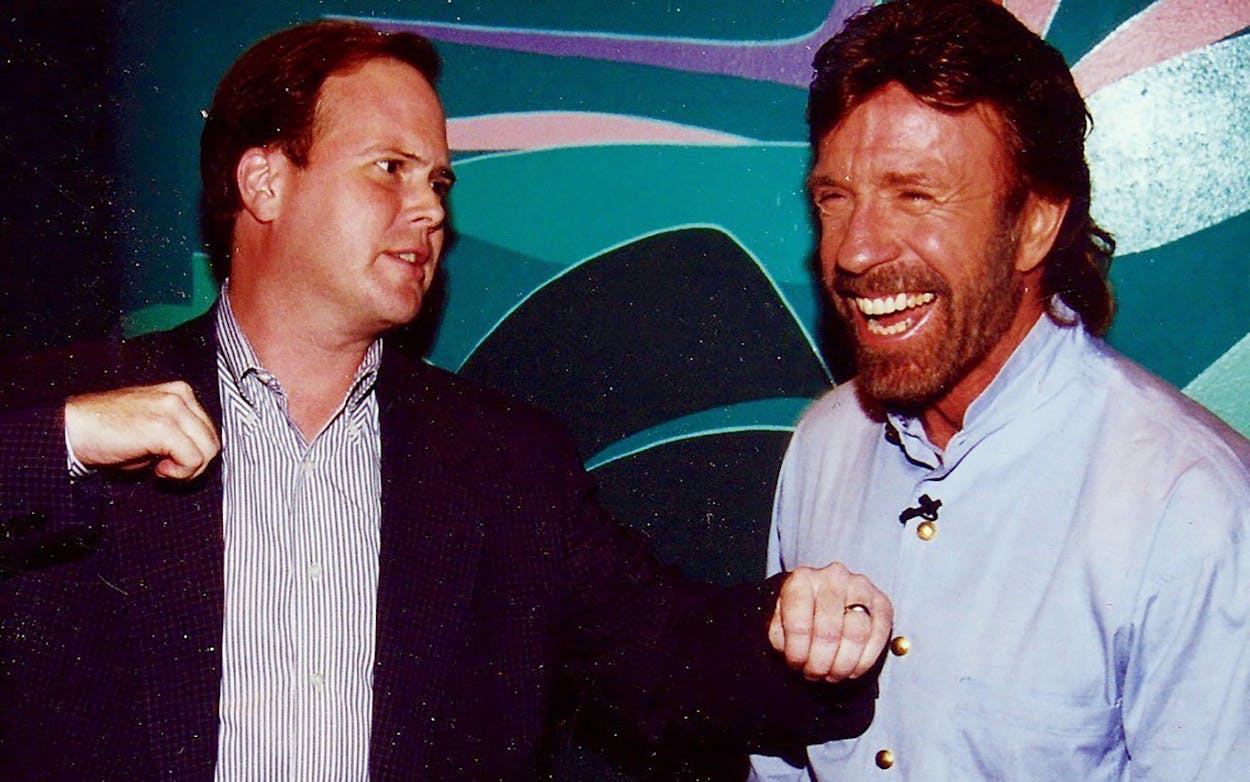

He wrote about Dallas’ young beauties, like Amber Campisi. And he wrote about all the actors that came here to put on television shows—from the martial arts actor Chuck Norris of Walker, Texas Ranger fame to all the people from the CBS show Dallas—Patrick Duffy, Linda Gray, and of course Larry Hagman, who for years mistakenly called Alan “Alan Pepper.”

Occasionally, there were complaints about Alan’s writing. One husband called Alan and asked him to stop describing his wife as “a social mover and shaker.” “She has advanced academic degrees,” he snapped. “Yes sir,” said Alan, and he promptly began calling the wife “Dallas’ Renaissance woman.”

And then there was Harriett Rose, whom Alan constantly referred to in his columns as the pint-size socialite because she was only 4 feet 10 inches tall. She got mad at him and told him to come up with a new nickname. Yes, ma’am, said Alan, and he graciously started calling Harriett “Dallas’ most petite partygoer.”

Alan was breezy, fresh, and funny—and he himself was so good-natured, so likable, and so darned non-judgmental that it was hard for anyone to stay mad at him for very long.

Soon, wannabe socialites and wannabe Dallas celebrities began hiring public relations people to get their names in Alan’s column. Usually reclusive members of the Dallas monied set were more than happy to return Alan’s calls.

Even T. Boone Pickens, of all people, loved reading Alan’s columns. He dropped what he was doing whenever Alan showed up at the office just to say hello. Despite their age differences, the two acted like fraternity brothers.

Boone even let Alan break the news in his column that he was getting married for the fifth time.

Some people think society columnists are, at best, masters of fluff. But Alan strangely had real influence in Dallas.

A lot of restaurateurs and nightclub owners, for instance, openly acknowledge that they wouldn’t have had the business they did without Alan writing about them. Indeed, Alan spent so much time at Al Biernat’s, taking notes about the comings and goings of the trendy steakhouse crowd, that Al named one of his dishes for Alan—‘Alan’s Traditional Eggs Benedict.”

And do you remember Alan’s columns about the restaurant war between Shannon Wynne and Gene Street—where they played pranks on one another? To this day, I’m convinced Gene and Shannon staged the whole thing just to make Alan’s column. At one point, when Gene was on a honeymoon in France, he made reservations to eat at a five-star restaurant. Shannon called the restaurant beforehand and bribed the chef to serve them chicken fried steak. Shannon immediately then called Alan to tell him what he had done. Gene, in return, had a horse’s head delivered in a box to Shannon’s office. And then he, too, called Alan.

You might think this is a stretch, but I always found Alan far more fascinating than any of the characters he wrote about.

He was an intense reader—his bookshelves filled with huge biographies on everyone from Edward VII to Howard Hughes to John Huston to all the presidents.

He collected contemporary abstract art—Roy Lichtenstein, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, and Jasper Johns.

And he found time to watch seemingly every movie and television show ever produced. Alan had a prodigious memory. He could quote lines from Apocalypse Now, Citizen Kane, Batman, and, of course, Dumb and Dumber.

And his form of exercise? How did he stay in shape? He played polo on weekends. He even kept polo mallets in the trunk of his Jaguar.

Oh, and then there was his diet—Chick-fil-A on Hillcrest for breakfast, Burger House or Hillstone or Al Biernat’s for lunch, and dinner at Campisi’s. Although the man could have eaten at every new chic high-dollar restaurant that opened in this city, he stuck with the basic food groups.

By the way, it was his love of a hamburger at Shannon Wynne’s old 8.0 restaurant that led him to the love of his life. In 1992, Alan came in to order the 8.0 hamburger and French fries, extra crisp, and there he met Jennifer Coles, a recent graduate of Texas A&M who was taking a year off before returning to A&M to get a master’s degree in psychology. He took one look at Jennifer and asked her out on a date. Absolutely no way, she said. He kept asking her out, and finally, she allowed him to take her to an Ella Fitzgerald concert. He knew every word to every song Ella sang. Jennifer stared at him, bewildered, and it wasn’t long before she too began to feel what has been known as the Alan Peppard gravitational pull.

By 1995 they were married. Soon, they had the twins—Isabel and Amanda. Later came Charlotte. The Peppards lived in a nice home in University Park. Alan put Lichtenstein and Stella on his walls. And he also purchased a $20,000 see-through Lucite piano so he could play Billy Joel and Don Henley songs—and “Blue Suede Shoes” by Elvis Presley.

Alan worked at the Dallas Morning News for thirty years. Toward the end of his reign, he drifted away from his column and wrote highly acclaimed stories, each several thousand words long, on the Kennedy assassination, Clint Murchison’s and Sid Richardson’s private island off the coast of South Texas, and Vice President George H.W. Bush in the days following the assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan. He wrote a piece for Vanity Fair on a feud in the Hunt family.

I was working for Texas Monthly then, and when he told me he was going to retire from the News and help run his father’s geological mapping company, I did my best to get him to write one more long story—a valediction, in a way—of his days as Dallas’ society columnist. I told him that society columnists were a fading breed. Newspapers didn’t invest in them like they once did. The Morning News, as a matter of fact, had decided not to replace Alan.

I said, Alan, just think of all the untold stories you could tell. We could call it “True Confessions of Dallas’ Most Famous Society Columnist.” You could finally tell that story of the man in Highland Park who had three homes for all of his girlfriends.

But he just shook his head and said no. He was ready to move on. He said he didn’t want to write a story where he rattled skeletons in people’s closets or revealed secrets that he had held for years. That was just not who he was.

And so, at the News, on September 2017, he threw himself a fantastic going-away party, having the food catered by—who else?—Al Biernat, all on Alan’s dime.

Everyone at the newspaper—even the cynical reporters who covered hard news at City Hall—dropped by to toast Alan.

The other day, I called Robert Wilonsky, who today is the lead metro columnist for the News. Robert started reading Alan in college, and even back then, he said, he realized that what Alan was doing was spectacularly difficult. Robert said, “Alan wrote about people I didn’t know, who lived in certain parts of Dallas I didn’t inhabit, and who went to certain places to spend money that I couldn’t afford. He gave me a chance to see, if only briefly, a world I would never be a part of. I always wanted to read about Alan’s world because it was, well, so much fun. And it was a world that was way more interesting than mine.”

And now that world is suddenly gone. Alan is not here to watch the twins head off to Vanderbilt later this summer. He’s not here to take Charlotte on one of their daddy-daughter dinner dates to Campisi’s. He’s not here to regale Jennifer with one of his hour-long stories about another historical biography he has just read.

And he’s not here to entertain us with his cast of characters.

It’s just hard to believe.

Whenever someone I know dies at too young of an age, I sometimes recall an old Episcopal saying that I first heard years ago:

Life is short, and we do not have much time to gladden the hearts of those who make this journey with us….

So be swift to love and make haste to be kind….

And, I’m sure Alan would add, make sure to laugh. Always laugh. Laugh like it’s your last day.

We will miss you, Alan.

- More About:

- Obituaries

- Dallas Morning News

- Dallas