BAYLOR, THE OLDEST UNIVERSITY in Texas, has added considerably to its number of spires in the past couple of years. The latest reach up to heaven from a parking garage that opened in August. The Dutton Avenue Office and Parking Facility is a massive structure—students call it the Garage Mahal—and holds 1,200 cars as well as a Chili’s Too and a Starbucks. The corner spires weigh seven thousand pounds each. There are two more next door at the magnificent new George W. Truett Theological Seminary building, which opened in January 2002, and another one at the new baseball stadium.

This is not to say that Baylor, whose 14,000 students make it the largest Baptist university in the world, is crazy about Christian symbols or iconography. In fact, one of the hallmarks of Baylor has always been that it has never physically broadcast its heritage, unlike, say, Notre Dame, a Roman Catholic school where crucifixes fortify the classroom walls. There are no crosses or statues of Jesus at Baylor, but there are plenty of bricks—”Baylor red” and set in absolutely straight lines, on perfectly laid mortar. There are also old limestone Georgian-style buildings, sprawling oaks, and meadows of lush green grass.

It’s the bricks that catch your eye, though—a lot of new ones in a lot of new buildings. You can’t walk very far across the clean, orderly campus, especially near the north end, without having to detour around a construction site. On the first day of school this year, students shielded their eyes from the dust rising at the site of the massive half-million-square-foot sciences building, set to open next summer. They took the long way around the huge new dorm complex, which will be ready for sleeping next fall. They stood and stared at the large domed museum, which will be completed next spring. Other structures have been open only for a few years—the giant student center, the law school, and the expansive sports park, with its baseball stadium, softball stadium, soccer field, and tennis center. The 158-year-old university looks like it just came out of the catalog.

Baylor, the pride of Waco, is changing. But these days, when people say they don’t recognize it anymore, they’re not talking about just the buildings. Baylor is only now emerging from its darkest summer ever. To outsiders—that is, people who don’t live in or obsess about the Baylor Bubble—the trouble began when a basketball player named Patrick Dennehy failed to call his mother and stepfather on Father’s Day and was pronounced missing. As a nationwide search began, his friend and fellow teammate Carlton Dotson was said to have shot him. Then a babbling Dotson was arrested in Maryland. Then the police found Dennehy’s body in a field outside Waco. Then, after allegations of improper payments to Dennehy and drug use on the team, coach Dave Bliss and athletic director Tom Stanton resigned. Then Bliss was heard on tape trying to get other players to lie and say that Dennehy had gotten the money from being a drug dealer. Then Dotson was indicted.

Poor Baylor. The truth is, even before Dennehy disappeared, the school was struggling with a crisis, a spiritual and cultural war that is threatening to rip the campus in half. On one side are the moderates and liberals—that is, Baptists who don’t go to church every Sunday—who like Baylor just as it has always been, a place where you could get a good, strong undergraduate education while the bells in the McLane Carillon played “Amazing Grace.” On the other side are conservatives who clamor for change—for progress, new programs, new buildings, and deeply religious professors who will bring back the faith they say has been diminished at Baylor. It’s the difference between being a good school in a Christian environment and a good Christian school. And it’s a big difference.

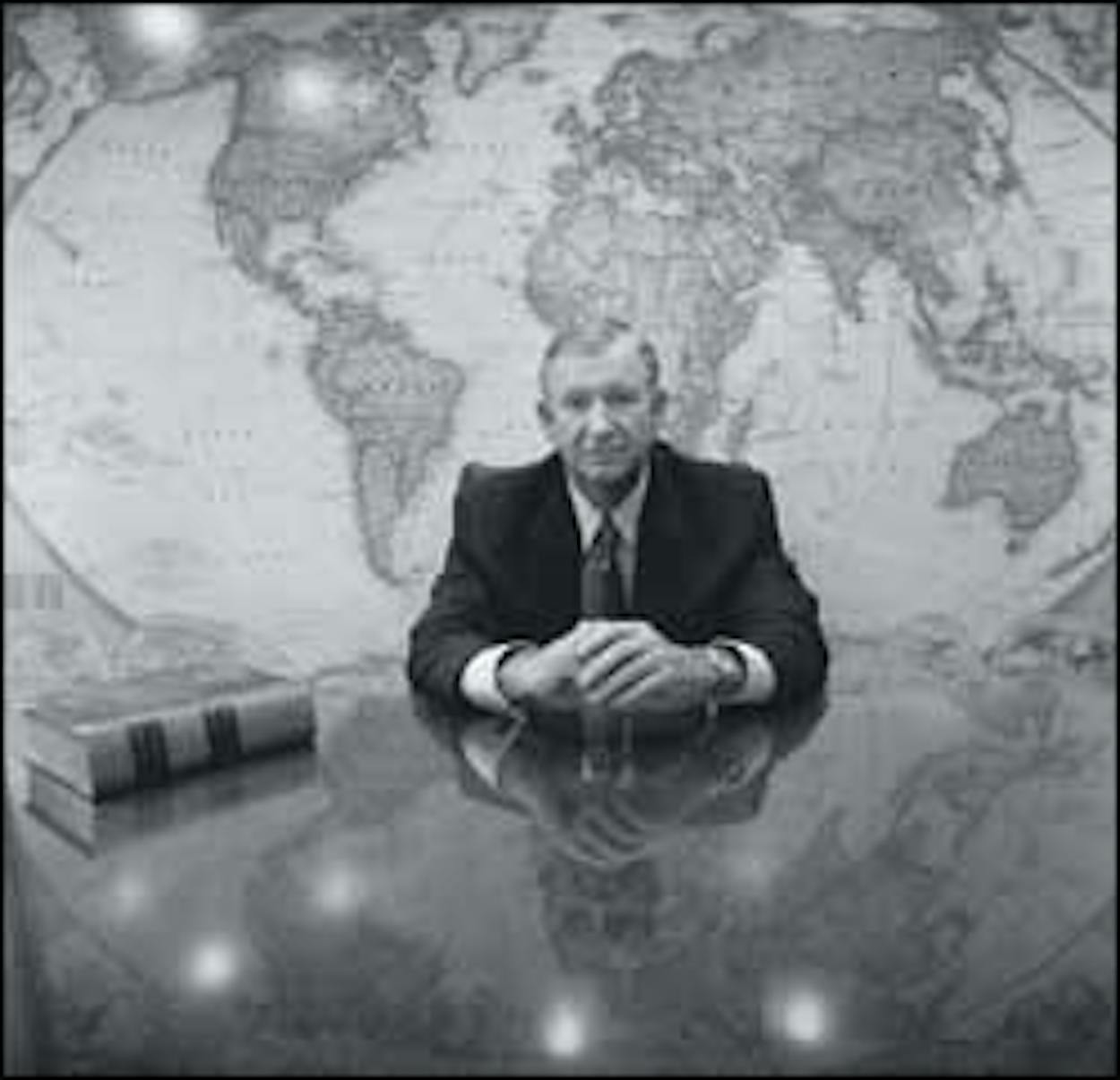

At the center of the war is Baylor president Robert B. Sloan, Jr., an ordained Baptist preacher and a son of small-town Texas, whose vision and personality are driving every single issue and building project there. The fact is, if the topic is Baylor these days, the talk inevitably turns to 54-year-old Sloan. To some, he’s a visionary, rescuing the school from secularism while bringing it into the modern world with a growth and research agenda that would put Baylor in the same league as Duke and New York University. He is a moral man, a man of the cloth, and he has ambition—just what this sleepy little place needs. To others, he’s a closet fundamentalist and a control freak who does not abide criticism. They speak of an atmosphere of fear and retaliation. And they aren’t just a random bunch of malcontents; their ranks include prominent alumni, faculty, regents, former regents, and the children of past presidents. Their cause was bolstered in August when the Houston Chronicle, until recently run by so many loyal Baylor alumni that the paper’s office amounted to a satellite campus, called for Sloan to resign. On September 2, three former chairmen of the board of regents also called for his resignation. A few days later, five current regents did the same.

Baylor is special, a place where generations of family members have ritually enrolled, a place graduates feel connected to by blood. They think with their hearts. They take sides. This struggle has destroyed friendships, alienated the faithful, and cast adrift die-hard Baylor supporters. It is not an arcane argument about academic freedom. It’s about the very identity of the university and the people who love it.

“Change is hard, hard on all of us,” Sloan told me on the second day of school. “We’ll either change, or we will die.” If Baylor isn’t careful, it could do both.

“DO I LOOK LIKE A FUNDAMENTALIST to you?” Sloan asks, smiling affably. He is sitting in his cozy offce in Pat Neff Hall. He is a six-foot-four-inch charismatic man with a big smile and big ears. In his elegant black pin-striped suit he has the well-groomed mien of a corporate executive, yet he’s been known to show up on campus wearing a T-shirt. He speaks in a soft Texas drawl, and his speech speeds up and slows down again like a preacher’s, the cadence of a man who loves to hear the sound of his own voice spreading the Good News. He rarely stammers. He doesn’t betray any doubt—about God, his vision for Baylor, or himself.

Since becoming Baylor’s president eight years ago, Sloan has indeed done some very un-fundamentalist things. In 1996 he reversed a long-standing ban and permitted dancing on campus. He helped bring Baylor into the famously liberal world of PBS, getting the campus its own public television station in 1999 and its own public radio station last year. He has hired Catholics and a few Jews. “If you look at Baylor today,” he says, “and you see the dramatic changes we’re embracing, that is not the spirit of fundamentalism. Fundamentalism fears change and rejects change. You see the commitment we have to science and research. Fundamentalism is historically anti-intellectual.”

At Baylor, fear of fundamentalism is not an idle worry. Relatively speaking—that is, relative to the rest of the Baptist world—Baylor is a moderate place. Indeed, it’s one of the last strongholds of the moderate wing of the Baptists. Baptists of all stripes are notoriously stubborn—fundamentalists stubbornly believe in the inerrancy of the words of the Bible, and moderates stubbornly believe in the priesthood of the believer (basically, that one has leeway in figuring out what those words mean). Since the school was founded by Baptist settlers, in 1845, the two sides have fought over everything from evolution to waltzing. Ultimately, Baylor became a good school in a Christian environment, and if you grew up Baptist in Texas—that is, if you were white and from a middle-class family—there was a place for you there, just like there had been for your mother and father. It was private, relatively cheap, and safe, a place where teachers knew the names of their students and took the time to explain things, whether it was Darwin’s theories or God’s grace. A quaint place where student-organization meetings were announced by writing in chalk on the sidewalks, where freshmen learned to make the bear-claw sign by curling their hand around their kneecaps, where friendships were made easily under the giant oak trees. A place where the football and basketball teams, dressed in old-fashioned green and gold, usually lost but did so with honor and a high graduation rate. A place with a typical student body—there were freaks and preppies, cool kids and science geeks. A place with an atmosphere of quiet faith. Students were expected to go to class but also to chapel. They’d raise hell at Saturday football games but bow their heads on Sunday mornings.

The last time the fundamentalists and the moderates fought this hard was in 1990, when the fundamentalists set their sights on taking over the university’s mother organization, the Baptist General Convention of Texas (which elected Baylor trustees, who in turn ran things). But then-president Herbert Reynolds, a moderate, got the university’s attorneys to amend the Baylor charter; now there would be a 36-member board of regents—Baylor would elect 27 and the Baptist General Convention of Texas the other 9. Baylor was safe, it seemed, forever. Or at least under its own control.

So when Sloan became the first preacher to run Baylor since 1961, alums and faculty took notice. Abner McCall, the president from 1961 to 1980, had been a lawyer; Reynolds was a psychologist. During their administrations, faith was embraced but so was science. “We teach religion in the religion department, science in the science department,” McCall once said. But upon his selection in 1995, Sloan made it known that he wanted to bring faith and reason back together again; this was a Baptist university, and it was going to start acting like one. Early on he sent a letter to all job candidates saying, among other things, that Baylor sought faculty who felt a “commitment to the universal lordship of the crucified and risen Jesus Christ.” Candidates had to submit a statement identifying their denomination, the name of their current church, and details about their participation there. Whereas under McCall and Reynolds questions of theology were kept out of the interview process and affirmations of faith were accepted at face-value, under Sloan, applicants were asked “Do you believe in the Trinity?” and “Why would a practicing Christian ever need a psychologist?”

In his first year as president, morale on the faculty plummeted. At a faculty senate meeting in September 1996, professors confronted Sloan about the language in the recruitment letters and the attitude of the administration, which was turning away—and scaring away—qualified candidates. After Sloan left the meeting, there followed what the student newspaper, the Baylor Lariat, called a “heated discussion,” and anthropology professor John Fox called for a no-confidence vote, though one wasn’t taken. Sloan was unmoved. Baylor was a private, Christian university, and it had a right to ask whatever questions it wanted.

Around the same time, attorney LaNelle McNamara, a Baylor alumna who served as mayor of Waco from 1986 to 1987, says she began getting calls from professors who claimed to have been fired or denied tenure because they were insufficiently religious or because they disagreed with the president on religious issues; she subsequently filed complaints against Sloan and Baylor with the American Association of University Professors. “It was the beginning of a mass purging,” she told me.

Sloan showed how much he wanted to marry faith and science in October 1999, when he opened the Polanyi Center, where the convergence of the two would be studied, and hired a man named William Dembski to run it. Dembski was a philosopher who’d gone to divinity school at Princeton and whose life’s work is “intelligent design” (ID), the theory that there’s a design to the universe and an intelligence behind it—namely, God; critics dismiss ID as “stealth creationism.” Before Dembski was hired, Sloan talked to almost no faculty members in the science, religion, or philosophy departments, and he didn’t announce his hiring afterward. Biology professor Richard Duhrkopf found out only when a friend e-mailed him. Duhrkopf, who knew all about Dembski and his work, told me he was dumbfounded: “My response was, there’s no way we would hire him.”

The faculty was outraged, some because they feared that ID would get a foothold at a major university, others because Sloan had failed to consult them. The chair of the faculty senate at the time, philosophy professor Robert Baird, told his colleagues that the dispute was “one of the most divisive issues to have arisen on the Baylor campus during my thirty-two years on the faculty.” The senate voted to request that the administration shut down the Polanyi Center, but Sloan dug in his heels and refused. Ultimately the name was changed, but the field of inquiry was kept open—after all, this was a Baptist university. Dembski is still on the faculty, as are others who believe in ID, much to the chagrin of science professors. Todd Copeland, the editor of the Baylor alumni magazine the Baylor Line, keyed in on what the outside world thought of Baylor when he picked up the late evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould at the Waco airport before a 2000 visit to the campus. Gould didn’t know much about Baylor, he told Copeland, but he knew all about the Polanyi Center—and that it was a disaster for the university.

The question has been asked since the Enlightenment: How can we believe in God and science at the same time? “If you believe God created the world from nothing,” Sloan says, “then there is nothing in the universe outside the creative activity of God.” Charles Weaver, a professor of psychology and neuroscience who has been an outspoken critic of Sloan’s, insists they’re separate. “Faith and science mix in philosophy,” he says, “and they mix in theology. They don’t mix in neuroscience.”

Scott Moore, a professor of philosophy who chairs Baylor’s Great Texts program, a component of the university’s Honors College, defends Sloan’s moves to reemphasize religion at Baylor. “Higher education has become so secularized that the common assumption is that smart people outgrow God,” he says. “We think that’s false.” Moore, who sits in on his department’s job interviews, says concerns about inappropriate interview questions are exaggerated: “I’ve never heard some of the things others have claimed to have heard. I have heard, ‘When you think about what it is you do, how does that contribute to your sense of your calling?’ The Baptist faith is an integrated life. I want people in my program whose lives are integrated.” Larry Lyon, Baylor’s dean of the graduate school, says that two questions are typically asked of job candidates: “What is your faith?” and “How is your faith put into action?”

But applicants claim to have been asked other questions, including “How would you integrate the concept of original sin in operations management?” and “What would you do if your son told you he was a homosexual?” Weaver, a Presbyterian elder and Sunday school teacher who has taught at Baylor for fourteen years, believes that he would not be hired at Baylor today: “If I were asked how I’d integrate faith in my classes, I would say, frankly, that they’re two separate realms. As a scientist, I have to look at the world objectively. It would be a misuse of my position to get up in class and talk about my personal faith.”

But doesn’t Baylor, a religious institution, have a right to ask professors and potential professors about their faith? “Baylor absolutely has that right,” Weaver says. “But the kinds of answers it accepts will determine whether it remains a great university.”

JACLANEL MCFARLAND REMEMBERS THE DAY everything changed. It was New Year’s Eve, 1994, and Baylor was playing in the Alamo Bowl at the Alamodome, in San Antonio. The university was in turmoil, and not because everyone realized that this was the last bowl game the Bears would play for a long time. Reynolds was soon to become Baylor’s chancellor, and the search for a new president had been going on for more than a year. The regents’ first choice for a replacement hadn’t worked out, so they had to find someone else. That evening McFarland, a Houston lawyer who had graduated from Baylor and was elected to the board of regents in 1991, nominated Robert Sloan, a young professor who was the new dean of Truett Seminary. He appeared to have good Baptist credentials, and he was bright. Yes, he was an inexperienced administrator, but this was only four years after the charter change, and Baylor was still under attack from the fundamentalists. Perhaps, McFarland thought, a respected and conservative member of the faculty—and a preacher to boot—would be an acceptable choice.

McFarland ignored warnings from a couple of colleagues, she remembers. “They said, ‘He’s like a German theologian. He’s very dogmatic. It has to be his way.'” But the search had taken too long; it was time to move on with the business of running Baylor. “In retrospect,” she says with a laugh, “boy, do I understand what they were saying.” McFarland wasn’t the only early supporter of Sloan’s to later change her mind about him. John Wilkerson is another current regent whose backing was instrumental in getting Sloan the job; he has since become highly critical of the president and his plans. And one of Sloan’s biggest enemies today is Bette McCall Miller, the daughter of former president Abner McCall. “My first thought when he got appointed,” she says, “was that he was a good man, a smart man, a strong Christian man, a very honest man. It wasn’t until later that I saw the arrogance, deceit, and vindictiveness.”

Robert Bryan Sloan, Jr., was born in the West Texas town of Coleman in 1949 and raised in Abilene. His parents had both grown up on farms but gone to college. His mother became a teacher and then got a master’s degree and became an educational psychologist. His father was a traveling insurance salesman who never graduated from college yet still studied for the bar and passed, becoming, Sloan says, a licensed attorney as well as a CPA. “He was an Abe Lincoln-type guy,” Sloan says, “very much self-taught.” Sloan went to Baylor, where he was a walk-on on the baseball team and majored in both psychology and religion. After graduating, in 1970, he went to seminary at Princeton and studied in England and Switzerland, where he got his doctorate in New Testament theology at the University of Basel. He pastored at various churches, including a two-and-a-half-year stint at the First Baptist Church in the West Texas town of Roscoe. After three years teaching at the Southwestern Baptist Seminary, in Fort Worth, Sloan joined Baylor’s religion department in 1983. He was a popular professor, prone to dropping references to Freud and Hamlet into discussions of Jesus and Moses. He became the founding dean of Truett Seminary in 1993. Running the small school—it had 51 students—was the only administrative experience he had when he was appointed in 1995 to replace Reynolds as president.

The vote of the regents was quite close, McFarland remembers, with Sloan barely beating out the other finalist, a Baylor biology professor and vice president. Eventually she would wish he had lost. Over the next eight years she would become increasingly frustrated with Sloan’s vision for Baylor and his leadership style. She raised a fuss about the Polanyi Center, spoke up when Sloan was discovered to have made plans to buy a $2.3 million airplane without consulting the board (the regents ultimately gave him permission), and opposed a massive tuition increase that he had proposed. For her outspokenness, McFarland says, she was rewarded in May 2003 with the news that a committee of the board of regents was investigating her for allegedly tipping off her son’s fraternity about the identity of an undercover narcotics agent posing as a student. McFarland vehemently denied the accusations; after two months and howls of protest from faculty, alumni, some dissenting fellow regents (“I know exactly what took place,” says one who wishes to remain anonymous, “and they had not one shred of evidence”) and former regents (Randall Fields, who chaired the board from 1995 to 1997, called the investigation “a witch hunt”), the matter was dropped because of “insufficient evidence.” McFarland believes she knows how the whole thing came to be. “I think Robert did it on his own,” she says, “without telling [current board chair] Drayton [McLane].” Sloan denies it. “What I did,” he told me, “came as a result of information from law-enforcement officials.”

McFarland is by no means the first member of the Baylor family to suggest a link between criticism of Sloan and negative consequences. Henry Walbesser, a computer-science professor, was the dean of the graduate school when Sloan became president. In an October 1996 story in the Dallas Morning News about the turmoil at Baylor in Sloan’s first fifteen months, Walbesser used an impolitic choice of words when talking about how threatened lawsuits over religious discrimination might finally get the administration’s attention: “It is almost like the story of the jackass and the two-by-four. You’ve got to get the person’s attention, and you whack ’em.” Walbesser says he told Sloan that it was just a metaphor, “but he took it personally.” Walbesser was subsequently fired from the deanship, and, he says, he’s been retaliated against in salary negotiations and requests for sabbaticals ever since. (Sloan says he can’t talk about salary situations, but he does say, when asked about Walbesser, “People want to claim retaliation when that’s a way to shift responsibility, by looking at someone else’s motives.”)

This summer, Walbesser crossed Sloan again, announcing on August 20 that he was going to call for a no-confidence vote on the president in the faculty senate, which would then prompt the board of regents to consider firing him. The next day Walbesser was told that he’d been kicked off the senate because of an obscure rule, never before enforced, that forbade missing more than four meetings. Walbesser says he had missed the meetings because he was doing research in New Zealand and that he had found a substitute to attend in his place. “Somebody went through that rule book with a fine-tooth comb,” he says. “I would suspect maybe somebody in central administration.” Sloan denies any involvement. “I don’t have the authority to remove anyone from the faculty senate,” he says, adding, “I try to live my life honorably. I take very seriously the Christian mandate against retaliation.”

Sloan’s adversaries don’t believe it. “There’s a vindictiveness in all of his firings,” says Lewis Barker, who taught psychology at Baylor from 1972 to 2000, when he grew weary of fighting with Sloan and left to become the chairman of the psychology department at Auburn University. Barker cites several cases of faculty who engaged in behavior he says was disapproved of by Sloan, from having an affair to being openly critical of the administration. “In each of these cases,” he says, “there was no due process. Robert judged them and found them guilty.”

One of the more egregious instances, says Barker, is that of John Fox: “What he did to Fox gets closer to evil. Robert dismantled this man’s life in a way the Mafia should study.” Fox was one of the first people to challenge Sloan; he was the one who proposed the no-confidence vote back in September 1996. After twenty years of teaching anthropology—and fourteen years after the university had granted him tenure—Fox was fired in 1997 following accusations of sexual harassment and of drinking with students at a field school in Guatemala. Fox denied the charges and sued, claiming that he was really fired because of the no-confidence motion and that his tenure had been taken away unlawfully; he claimed that Baylor changed the rules for tenure revocation just three days before his revocation hearing. A jury agreed that Fox’s due process rights to tenure were violated, and he won two years of back pay. Baylor appealed and won, but Fox’s attorney, McNamara, says that in mid-September she filed a motion for rehearing before the Texas Supreme Court. Asked about the suit, Larry Brumley, Baylor’s associate vice president for external relations, says, “The claim that this was retaliation for Fox’s no-confidence posture is completely without merit.”

Graduate dean Lyon defends Sloan’s handling of personnel issues: “I would not, in all candor, see Robert Sloan as having a more vindictive personality or a thinner skin or a stronger ego than most of the other leaders I’ve worked with—a successful football coach, successful business people. They do have a personality type that helps them be good leaders. He is more sure of himself.” So much so, say some professors, that Sloan has taken control of areas not generally under his command, such as hiring, which they complain he’s taken out of their hands. Usually, a department picks a person it wants or “rank-orders” several candidates. Sloan ended this process, sitting in on interviews along with the chair of the department, the dean of the college, and the provost. According to a November 2002 faculty survey, as many as 30 percent of the candidates recommended by department search committees were turned down by Baylor administrators. “That’s almost unheard of,” Professor Weaver says. “The faculty are the ones capable of judging the competence of the candidates.” By comparison, former president Reynolds says that from 1973 to 1995 the turn-down rate was only 2 percent.

Sloan’s antagonists include alumni too, and their wrath is in part related to his dealings with the alumni association. In the spring of 2002 Sloan announced a plan to set up the Alumni Services Division (ASD); the university would also publish a magazine, Baylor Magazine, that would be sent free to 100,000 alumni, as well as to faculty members and the parents of students. The only problem was, Baylor already had an alumni group, the independent Baylor Alumni Association (BAA), and a magazine, the award-winning Baylor Line, which the association had been publishing since 1946. Sloan notified the BAA that the money the university was to give it for the next year ($350,000) would be discontinued. He defended the move, saying that the BAA, a membership organization, had not been doing a good job of communicating with all alumni; for example, fewer than a quarter of Baylor grads paid dues and received the Baylor Line. Sloan said the new group and magazine would be for all alumni.

Members of the BAA say they knew their organization needed to extend its reach, which is why they’d gone to Sloan in August 2000 with a costly long-range plan that they thought he had agreed to; then they began drawing from their endowment to implement it. Almost two years later, Sloan set up the ASD, and soon he had hired away most of the BAA’s staff. Tyler mayor Joey Seeber, a member of the BAA board since 1992 and its president in 2001, hasn’t forgotten. “The BAA came up with the plan, paid to develop the plan, brought it to Baylor, got their agreement, spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to develop and implement it, and then it was hijacked by the administration,” he says. “If Sloan was not dishonest, he was at least deceptive in that August meeting.”

Sloan disputes that. “We agreed on pursuing a possibility, but we never agreed on a budget,” he says. “We bogged down over the numbers.” Yet Copeland, the editor of the Baylor Line, says the problem is less what Sloan did or didn’t do than how he treated the BAA: “The concerns they had about us were legitimate, but the way they did it was a disaster. The sad thing is, he made us feel like we were under attack and couldn’t trust him.” Says BAA executive-committee member Jack Loftis, the former editor of the Houston Chronicle: “The administration showed total disrespect for the alumni association in starting up that magazine. I felt a personal assault.”

Seeber says Sloan had been upset about several issues of the Baylor Line, including one with a short article about drug and alcohol abuse on campus and another about the Baylor graduates who were trial lawyers involved in the Texas tobacco settlement; the latter was said to have upset a big university donor. Sloan also didn’t like the letters page, which published letters critical of him and the university. “It’s all about him being in total control,” says McFarland. “You either agree or you’re ostracized.” Sloan agrees that there were some issues that bothered him but denies that was the reason he started his own magazine. Regardless, the upshot is that he now has purview over Baylor Magazine, which is published by Baylor’s Office of Public Relations and which features an article in the current issue titled “Breaking News: Faculty Speak Out for Sloan.”

“Baptist ministers by nature are accustomed to being in charge,” says Texas Monthly writer-at-large Jan Jarboe Russell, who herself grew up Baptist and wrote about Baylor and Sloan for this magazine in 1991. “They’re not used to being questioned. In Baptist culture, the ministers are more powerful than any politician. And their ambition is clouded by the attitude ‘I’m just here to serve God.’ I think Sloan is a vigorous defender of what he believes to be true.”

“ROBERT SLOAN’S PASSION FOR THIS INSTITUTION is without equal.” It was August 25, and Baylor spokesman Larry Brumley was introducing his boss at the annual Baylor President’s Media Luncheon to a crowd of two hundred local businessmen, government officials, and journalists. “Robert Sloan loves this university, its students, its faculty and staff, and its alumni and its legion of friends who believe in its mission: to change lives and impact the world. His tenure has not been without controversy, but what leader who presides over an organization of Baylor’s size and influence has not encountered turbulence? Bold, innovative leadership stirs emotion—it stretches conventional thinking, and it pushes people outside their comfort zones.”

Before the luncheon started, Sloan had worked the room like a politician, going from table to table, shaking hands and greeting friends and supporters. After Brumley’s introduction, he got up and did what he has been doing for much of the past two years: He preached about his baby, Vision 2012, one of the most ambitious programs any major university has ever conceived. “We are less than two years into this endeavor,” Sloan said. “There are surely things we wish we could go back and fine-tune or redo. But we have accomplished much in our goal to put Baylor into the upper echelons of American universities, while reaffirming and strengthening our Christian mission.”

Sloan spoke of the economic benefits of Vision 2012 and then showed a video of all the new construction: the $15.5 million Dutton Avenue Office and Parking Facility, the $33 million North Village Residential Community, the $23 million Harry and Anna Jeanes Discovery Center in the Mayborn Museum Complex, the $103 million Baylor Sciences Building. He talked about “Baylor’s growing research agenda” and showed another video of busy students and professors writing formulas and doing experiments. “Baylor aspires over the next ten years to develop into one of America’s leading Christian research universities,” the narrator intoned, noting the university’s work on finding a cure for cancer, keeping air and water clean, and doing “out-of-this-world” studies on semiconductors. When it was all over, Randy Riggs, a Waco city councilman and Baylor grad, told me, “It all sounds good. Progress is good, but at what cost? We don’t want to lose what makes Baylor special.”

Sloan announced Vision 2012 in 2002 to almost immediate support, and alarm. It was a ten-year plan with twelve imperatives—for example, recruit faculty “who embrace the Christian faith” and who are “leaders . . . in productive, cutting-edge research,” increase the number of graduate students by 25 percent, build “outstanding facilities,” build a $2 billion endowment—all of which would vault Baylor into tier one of American universities, as defined by U.S. News and World Report‘s annual rankings (the latest U.S. News overall rankings have Baylor at number 78).

Vision 2012 is risky, and to some it is worth the risk. It was an “audacious and much-needed experiment in American higher education and religious life,” wrote Dallas Morning News columnist Rod Dreher. Baylor was doing what it had always done to survive over the previous century and a half: It was adapting to the modern world. While critics noted the paradox of returning to one’s faith-based roots while spending so much money on scientific research, Sloan’s supporters reveled in it.

Many faculty and alumni liked Vision 2012, or at least parts of it, but they worried about how to implement it. Ten years is too quick, they said, to try to make a move like this, to try to compete with Yale and Rice. Plus it was expensive: Baylor had to borrow $247 million it didn’t have, and Baptists, prudent with their finances, generally don’t like debt. Donations were down because of the lagging economy (Vision 2012 was passed by the board of regents two weeks after 9/11), so to pay for all the new buildings, the package came with a staggering 44 percent rise in tuition and fees, from $11,990 in 2000 to $17,214 in 2002, which many worried would price Baylor’s traditionally middle-class students right off campus. Sloan argued that even with the hike, Baylor was still a bargain.

Those opposed to the plan pointed to the religious language and also worried about the emphasis on research and the hiring of research-oriented faculty, saying that all that time writing scholarly articles and doing lab work would keep professors out of the classroom, to be replaced by graduate assistants. “We’re going to be a mediocre research institution and lose what is the most valuable part of this place,” says Professor Walbesser. Even pro-Vision 2012 professors like Scott Moore acknowledge some concern with the deterioration of Baylor’s traditional teacher-student relationships, though, he says, “we’re a long way from that happening.”

The plan’s most notorious feature was its division of the 539 full-time faculty members into two groups. The “A” faculty were those hired before 1991 who chose to teach; the “B” faculty were newer hires, who came on as researchers or research-teaching faculty (older faculty who wanted to do research were also in the “B” group). The A’s and B’s were judged by different standards when it came to tenure (the former got it basically by teaching, the latter by publishing), raises, and promotions, with the result being that the older teachers began to feel passed over by the new ones and even targeted by the administration. “Part of Sloan’s plan is to replace the faculty,” former Baylor professor Barker says, “and it’s occurring.” Older professors complained of a caste system that favored the younger, more enthusiastic, and more evangelical professors (in the first year of Vision 2012, 62 percent of new hires were Baptists, compared with 49 percent of the general faculty). A faculty survey, commissioned by the administration, was released in July, confirming the split. Among tenured professors, only 29 percent expressed any confidence in Baylor’s direction, as opposed to two thirds of the newer tenure-track faculty. The older faculty felt that teaching had been devalued. Professors spoke of “a climate of fear and revenge.” Only a quarter of all faculty agreed that there was a “high degree of trust within the university.” (Sloan now says the administration is reconsidering the A and B split.)

“Everybody’s afraid of him,” a regent told me. “If you’ve got a cousin or a sister or an uncle working at Baylor and you criticize Sloan, he or she is going to get fired.” (In the course of reporting this story, several professors said they were too afraid to speak out, even off the record.) Sloan denies people have anything to be afraid of. “A university should encourage questioning,” he says. “I do think people should be civil. People are engaging in whisper campaigns and carrying their disagreement outside the family to embarrass the university.”

IT WOULD BE HARD TO HAVE a worse summer than Baylor just had. First, there was the furor over McFarland’s case, which mobilized Sloan’s opponents. Then, in June, feeling the heat from criticisms of Vision 2012, Sloan sent an unprecedented letter to more than 100,000 members of the Baylor family attempting to alleviate some of the “anxiety” he knew they were feeling. He acknowledged mistakes but wrote, “That is to be expected: The road we are traveling has no scouts.”

A few days later Patrick Dennehy, a junior on the Baylor basketball team, became a media star for all the wrong reasons, the lead story on CNN and Fox news. Allegations arose that coaches had paid Dennehy’s tuition and that they knew that some of the players had failed drug tests. Sloan set up an internal investigative committee, and on August 8 it told him that there were indeed major violations. The next day Coach Bliss and athletic director Stanton resigned. A few days later an assistant coach revealed tape recordings he had made in late July of Bliss trying to orchestrate a cover-up of the illegal payments made to Dennehy. In a new low for college athletics, Bliss was trying to persuade the dead student’s teammates to lie to the committee and say that Dennehy had paid for his tuition by dealing drugs.

To Sloan’s credit, he immediately put Baylor basketball on probation for two years. But as president of the university, he still had to face questions of his own. When Stanton quit, Sloan said that the athletic director “felt like, as a matter of leadership and integrity, he should step down, since these things happened on his watch.” Of course, they happened on Sloan’s watch too. How could a micromanager like Sloan not have known about that magnitude of trouble in the university’s basketball program? “The fact is,” says Sloan, “a modern-day university administrator must be able to delegate responsibility and hold people accountable.”

Baylor did its best this summer to put on a good face. On July 18, a couple of days after the McFarland investigation was dropped for insufficient evidence, the university held a Baylor Family Dialogue, a town meeting to talk about all the family problems. Reservations were so numerous that the meeting was moved from the Alumni Center (the BAA sponsored the event) to the massive Ferrell Center; 1,200 people came, and another 400 watched it live on the university’s Web site. The eight panelists—including Sloan, Drayton McLane, and Bette McCall Miller—talked about tuition and debt, the faculty’s lack of trust, and the job-candidate questions. Sloan was defended—for his boldness, for not being a fundamentalist—and he was attacked—for being vengeful and divisive. He promised to work hard on his leadership skills. “There have been many missteps along the way,” he said. “There will be many more tomorrow. But I have a single ambition for Baylor: that we be a university that takes seriously the confession, Jesus Christ is Lord.”

TRY TO IMAGINE UT OR OU having a “family dialogue.” The truth is, Baylor has always been different—small enough for everyone to know each other, big enough to have serious problems, and Baptist enough to drive everyone crazy. When the Baylor family fights, members feel the passion and vitriol that people in big, divided families feel. They fight from places where words don’t help matters, where their feelings about God and themselves and their families lie.

And so everyone has a strong opinion about Sloan. On the one hand: “I’m still not completely sold on Vision 2012,” says Mark Collins, a Houston attorney and Baylor grad whose wife is also an alum and whose daughter is a student there now. “But the heart and soul of Robert Sloan is to maintain respect in the academic world while keeping Baylor a Christian educational institution. We don’t have to be ashamed of our Christian beliefs. They’re not contrary to the search for knowledge and academic excellence.” On the other: “He’s a narcissist,” says attorney McNamara. “That is a character disorder. Everything revolves around him. He must be aggrandized at all times. Look at all the multiple phallic symbols that have appeared on campus!”

That’s the thing about symbols—to one side, they glorify God; to the other, man. Before the fall semester began, both sides mobilized for the battles ahead. A group of Sloan’s supporters gathered on campus to attack the media for exaggerating the chaos. At the fall faculty meeting, more than a hundred professors gave the president a standing ovation. At the first Baylor football game, people wore “I Support Sloan” T-shirts and buttons. Yet up in Dallas, thirty members of the loyal opposition met in secret and planned their strategy. Calling themselves the Committee to Restore Integrity to Baylor, they stepped up calls for Sloan to resign. Ex-president Reynolds, the Charles de Gaulle of the Baylor family, finally started talking publicly about the crisis and said he didn’t like what he had been seeing. “Over time,” he told me, “Dr. Sloan has brought into his inner circle a group of people with the same ideology. They’re here to transform Baylor, move it in a direction where there is more religiosity, more rules, more prescribed ways of doing things. And people are expected to fall in line.”

It’s unlikely that the president will step down anytime soon; it’s not in his nature, say his enemies. “The right people have resigned,” Sloan told me when I asked about the basketball scandal. “And I have a deep commitment to what’s going on here, what we’re doing at Baylor.” Only the regents can fire him, and they are generally supportive. Even after the faculty senate approved a vote of no confidence—the first in Baylor’s history—by an overwhelming 26 to 6 margin, Sloan remained unbowed. He seems to stand stronger against his critics; if anything, the increased controversy only ennobles his mission.

If he survives as president, Sloan will face the daunting task of holding Baylor together. The football team is terrible. The basketball team will be terrible (most of the best players transferred to other schools in August) and will certainly get hit with a major penalty from the NCAA. The school’s finances are shaky. In the fall of 2002, to protest the rise in tuition, the foundation Christ Is Our Savior took away $2.6 million in money used to give loans to students; this summer it said it wouldn’t renew a $5 million loan to Truett. Last year, either because of higher tuition rates or a sluggish economy, Baylor was 155 freshmen short of its target of 2,775, a loss of more than $2.6 million in tuition, and the number of students transferring to Baylor was down by about 75. This year’s enrollment will be up, Sloan says, but it won’t hit the target numbers. On Internet chat boards, alumni write of not giving money (“I hear reports of people all the time saying they’re taking Baylor out of their wills,” says BAA board member Seeber) or not sending their children to Baylor—or, at the very least, of not being able to afford it anymore. And next year things will almost certainly be worse. On TV all summer, parents of high school seniors heard about basketball players running amok, smoking pot and shooting guns. They heard a respected Christian coach try to defame a dead college kid. They heard stories of feuding faculty and a divisive president. This is the place they want to send their kids to?

In the summer of 2003 Baylor alums and students saw something unbearable—they saw themselves becoming like everybody else. Their coach was a cheat. Their athletes were violent and out of control. Their school was spending a lot of money it didn’t have and joining the academic rat race. Their students choked on the dust of a bunch of new buildings going up on campus. Their parents complained about how much money it cost to send them there. It was, they realized, a lot like the real world, the one outside the Bubble.