This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ever since the first Spaniard landed on our shores in 1519, foreigners have been coming to Texas, and always for the same reason—the hope of finding more freedom and more money than was available back home. In the last few years immigrants have streamed into Texas in unprecedented numbers (about 30,000 a year enter legally, which is surely only a fraction of the real figure), and in particular they have come to Houston. People from the oil-producing nations of the Middle East, Africa, and South America come because Houston is the capital of the oil business; people from nations that are poor, or totalitarian, or at war, or all three, come because Houston is now the best place for a person with no money and no friends to find a job. They come from Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Viet Nam, and dozens of other countries. Because Houston is so spread out, because it doesn’t have a single great immigrant neighborhood like the old Lower East Side of New York, even Houstonians don’t realize how many different people have moved there because they regard it as, in the short run, the most desirable spot on earth.

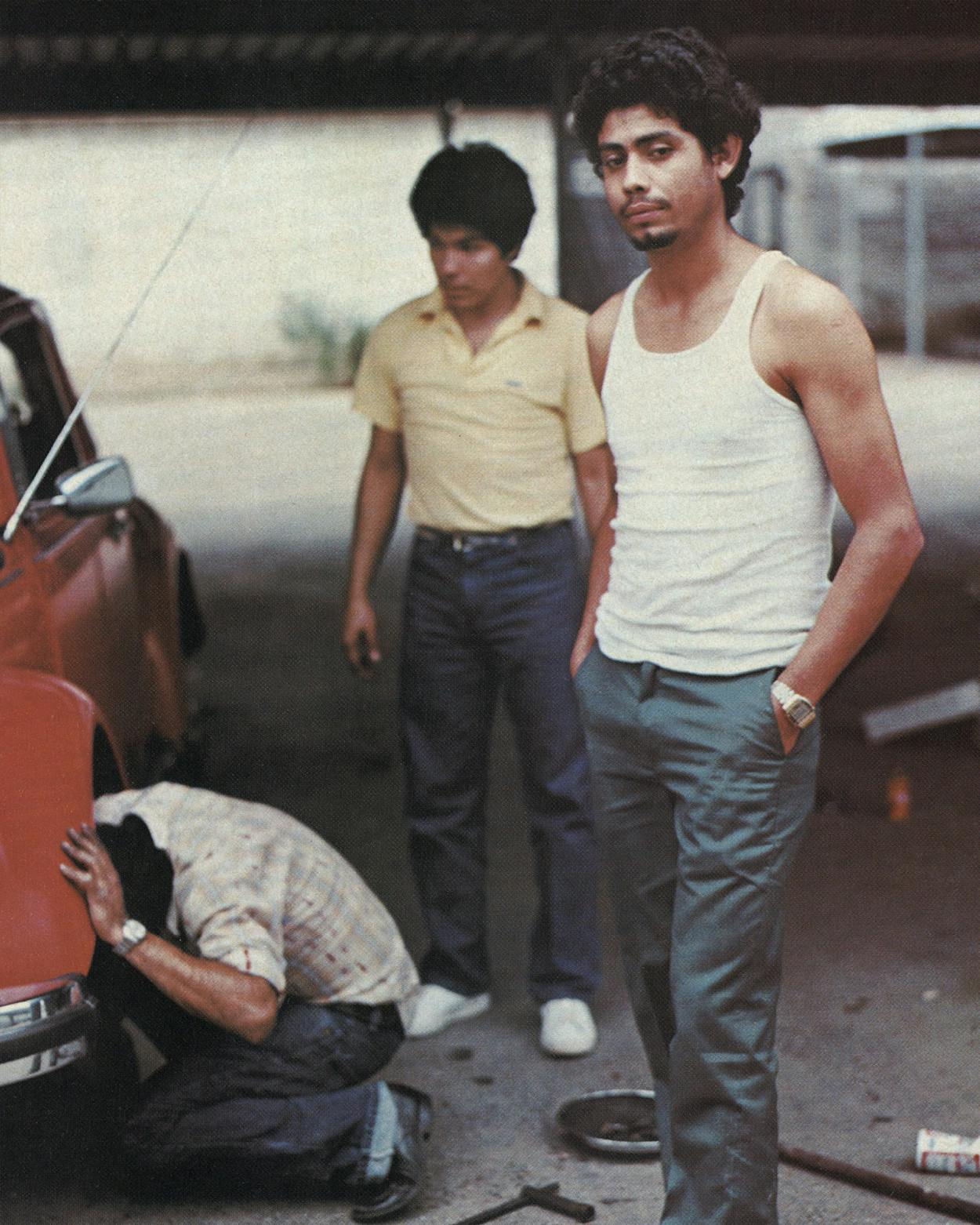

Anna Goslicka, who took the photographs on these pages, is an immigrant herself; she came to Houston from Poland four years ago. She spent six weeks taking pictures of three of Houston’s newest immigrant groups, representing three different cultures and three continents: Poles, Nigerians, and Salvadorans. Their financial situations vary from moderately well off (the Nigerians) to desperately poor (the Salvadorans), and in classic immigrant fashion, all of them are homesick and rely on their extended families for most of their pleasure and solace in life.

What will become of them? Back in the early days of the century, in New York, compassionate observers of immigration universally believed that the Jews, the Italians, and the Irish in America would always live in poverty and squalor. It was widely feared that American civilization itself would be destroyed by the immigrants as they diluted the nation’s racial purity. What really happened was exactly the opposite: they brought the country vitality, drive, and hope, all qualities that are still and will always be in too short supply here. Inexorably, they drifted away from their own well-defined cultures and toward our newer and more rapidly changing one. If the record of history holds, the immigrants in these pictures will, after lives of struggle, propel their children into the middle class, where they’ll be unusually religious, hardworking, and, if patriotism is the measure of nationality, more American than most Americans.

Poles

Poles are coming to Houston because their own country, under martial law and the constant threat of Soviet invasion, can no longer provide them with what they consider a decent life. It did provide the people in these pictures with a decent living—better than they now have in Houston—but that’s a different and, to them, less important matter. The Ciechocinskis, for instance, were financially well off in Poland; they got out four days before the imposition of martial law last December, and now they’re starting over practically from scratch. They don’t speak any English; their eldest child, Grzegorz, speaks some Spanish because that was the language spoken by his co-workers at the farmers’ market where he got his first U.S. job. They live in a rented house on the north side of town, filled with furniture donated by the parishioners of a nearby church. But they’ve found jobs—Stesan Ciechocinski is a surveyor and his wife, Jan, is an engineer—and their twin girls are learning English in school. They are more worried that their kids will forget Poland than that they’ll fail to become Americanized. The Sadzas, chemists and, like the Ciechocinskis, supporters of Solidarity, left Poland for a vacation in Greece, then fled to Houston. Stanley Pawlowski, also an ardent Solidarity supporter, came here eight years ago, and now he’s an American-style success. He owns a Polish restaurant in Southwest Houston, pricey enough that more recent Polish immigrants can’t afford to eat there.

Salvadorans

The Houston population of immigrants from El Salvador has been burgeoning lately in response to the state of near–civil war there. The people in these pictures would have had good reason to fear almost constantly for their lives back home; small wonder they chose to leave. But the process of emigration from El Salvador is arduous. The U.S. government considers Salvadorans “economic” refugees—that is, in the official view, they come here in search of money, not freedom—and keeps their numbers tightly restricted. Therefore most of them are illegal. They have to get into Guatemala, then across Guatemala and into Mexico, then through the length of Mexico. Even if they can get into Mexico legally, they can’t get into the United States, so many hire “coyotes” to smuggle them across the Rio Grande (the going rate for their services is $800). Then they have to get to Houston, where the jobs are. They usually don’t speak English, and quite often they work for less than the minimum wage and live in crowded, unpleasant conditions. Still, the first glimmers of a permanent Salvadoran community in Houston are appearing. A run-down pool hall on the east side of town, El Piquito de Oro, has become a Salvadoran hangout; there is a new Salvadoran restaurant, El Nahuat, on Washington Street in the shadow of downtown; Galindo’s, a Mexican restaurant, has been working Salvadoran dishes into its menu to attract the Salvadoran trade. And most important, the immigrants’ children are in the Houston schools, which don’t give information about students to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Nigerians

If Poles and Salvadorans are drawn to Houston by their nations’ tragedies, Nigerians come because of Nigeria’s good fortune, and many of them become real immigrants only gradually and against their original intentions. Their homeland is fairly stable and prosperous—it’s a member nation of OPEC—and the Nigerians who come here are usually well-to-do young people (as well as outstanding students) looking for educational opportunities, since Nigeria is at that stage of its development where its economy demands high-technology skills that its own schools aren’t yet able to teach. In Houston, the school they go to is Texas Southern University. The Nigerian students at TSU arrive fully intending to go back home. They feel that the other students don’t fully accept them and that the institution of marriage is taken more seriously back home. They take great care to keep up their ties with Nigeria and to create occasions to wear their nation’s traditional clothing. The Nigerian Students Association takes itself extremely seriously; at the meeting pictured here, the members were discussing Jesus Christ’s skin color but dropped the subject when one of their number said religion was too controversial for an august group like theirs. Careful minutes are kept of all the students’ association meetings, on the grounds that the members’ experiences in America are an important matter—personally, educationally, even patriotically. And yet, America has a way of getting its hooks in. Benson Okoronkwo, a pharmacy student and the president of the students’ group, wears cowboy boots. Robert Ojaruega, the vice president, is thinking about staying in Houston. His youngest child was born here, and he thinks that may mean he can get his visa changed and get a job. The opportunities, to use his word, are better in Texas, and he loves his bland Houston apartment. His three youngest children seem completely American. But the Ojaruegas wouldn’t let their picture be taken in their kitchen—Nigerian men aren’t supposed to go there, and they were worried that somebody back home might see them living by American customs.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Houston