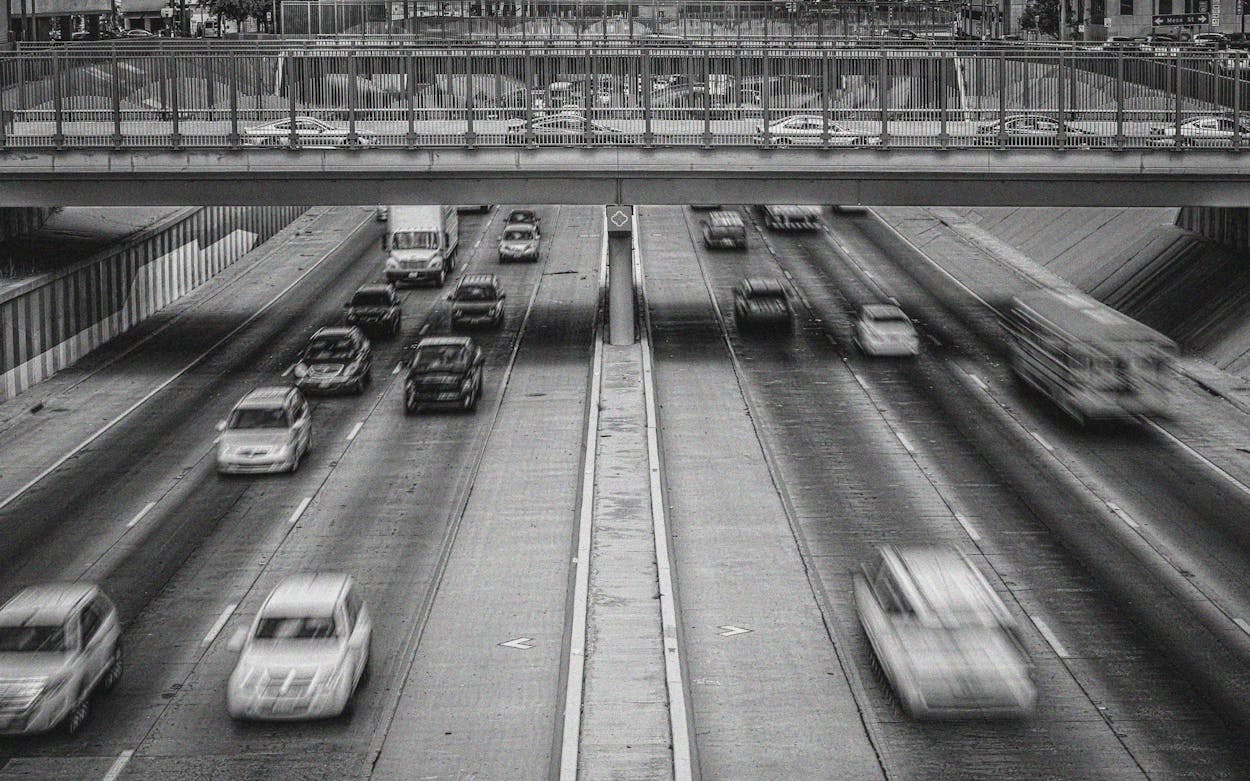

Around 5 p.m. on a spring Friday, cars and freight trucks motor through downtown El Paso on Interstate 10. You can hear the hum of vehicles buzzing across pavement from the pedestrian bridges that span the interstate. The scene looks like a success story for a state whose transportation policy prioritizes moving vehicles quickly. But the Texas Department of Transportation doesn’t see it that way.

The state agency cited congestion as a key reason for its support of a highway-widening project, still years away from completion, in the 5.6-mile stretch of downtown El Paso from Executive Center Boulevard to Copia Street. TxDOT’s models, which some of the plan’s opponents dispute, predict the number of vehicles moving through the area per day will increase from the 200,000 there were at peak afternoon traffic in 2018 to 300,000 by 2042. According to TxDOT public information specialist Jennifer Wright, the four designs the agency is considering (not counting the no-build option) all would create a highway segment with five lanes in each direction, one of which would be an “adaptive lane” that could be designated for specific vehicle types such as buses, trucks, or autonomous vehicles.

But many opponents don’t think TxDOT is solving a problem. The Texas Transportation Institute ranked the downtown segment of I-10 slated for widening as the 163rd most congested road in the state. TTI’s data for a segment of I-10 that includes the stretch designated for widening show that cars travel a little over 60 miles per hour at “free flow” times and around 55 miles per hour at peak traffic. A consultant hired by El Paso County to evaluate the highway proposal noted the lack of a bottleneck. “I really don’t understand the justification for it,” said Veronica Carrillo, an El Pasoan whose neighborhood would be affected by the project. “I think that’s concerning for me, because the traffic doesn’t slow down between Copia and Executive.”

Carrillo’s brother, Brandon Carrillo, has raised concerns about air quality in the area around the highway, particularly given that adjacent neighborhoods have average household income levels between around $22,000 and $47,000. Opponents say the expansion will attract more cars, which produce air pollutants that can cause and exacerbate health issues such as asthma. The Carrillos and other opponents of the highway plan have called for a thorough review of the region’s air quality and I-10’s role in local pollution. The Environmental Protection Agency already designates El Paso County as a nonattainment area, meaning that it does not meet national air-quality standards.

Supporters of the project see moving vehicles more quickly as a way to reduce air pollution, because idling cars stuck in traffic produce harmful emissions. And TxDOT says that even if the affected stretch of I-10 doesn’t appear to have a congestion problem now, traffic issues are likely to arise, based on the agency’s 2042 projections. The $750 million project also aims to fix structural issues, such as by heightening bridges to provide clearance space for tall trucks and addressing deteriorating pavement conditions. Both backers and opponents of the overall project say they approve of those improvements.

Eduardo Calvo, executive director of the El Paso Metropolitan Planning Organization, said there is some truth to induced demand—as more lanes are added, more cars will inevitably fill them. But he said it’s unlikely to happen in downtown El Paso: “I would argue that fixing a bottleneck here in downtown is not the same as adding an extra lane in the outskirts of the city where you are encouraging sprawl.”

Calvo, who spent nine years working for TxDOT, finishing as the director of advance transportation planning, said he sees I-10 as the “backbone” of the region’s transportation network as it prepares to accommodate an incoming boom in trade thanks to more companies onshoring production to Mexico for access to the United States.

Calvo and other supporters of the project feel that the region can’t afford to miss an opportunity for infrastructure investment on this scale. They argue that El Paso, which is closer to San Diego than Houston, is often ignored by the rest of the state. The past three years, TxDOT has spent more in its Amarillo ($753 million) and Corpus Christi ($1.2 billion) districts, even though both have smaller populations than El Paso, where $724 million has been spent.

Some El Pasoans are wary of TxDOT I-10 proposals. Work on the I-10 Connect initiative was completed in 2021. The construction added ramps feeding into the Bridge of the Americas but also cut off other roads’ access to the area’s only toll-free bridge. Now the line of waiting vehicles often snakes from the bridge onto I-10—sometimes extending all the way back to the downtown section under consideration for expansion. Calvo calls the backups “something of concern.”

Among problems stemming from the project, residents in the San Xavier neighborhood reported cracks in their ceilings and walls due to vibrations from the construction. “This neighborhood has been sliced and diced for the last eighty years with transportation projects, and you can see it’s surrounded everywhere,” said Veronica Carbajal, a Texas RioGrande Legal Aid attorney who is helping neighborhood groups submit complaints.

Indeed, San Xavier is boxed in by major thoroughfares: Interstate 110, Paisano Drive, and U.S. 54. Children walk along a bridge above idling trucks to Zavala Elementary School. A skinny parking lot separates the school’s playground from the highway. An engineer hired by Carbajal to look into the complaints wrote that “the I-10 Connect project has concentrated sources of air pollution around the San Xavier neighborhood and surrounding areas.”

The federal government plans to spend $600 million to widen the centrally located Bridge of the Americas. Neighborhood advocates would prefer to see the exhaust-belching freight traffic pushed farther north into the Anthony Gap, north of the city, via another proposed TxDOT project called the Borderland Expressway. Brandon Carrillo said he understands that moving trucks to the outskirts of the county shifts pollution to another part of the region, but he noted that air in the downtown area already has the city’s highest levels of diesel particulate matter.

While some neighborhood groups are devoted to opposing the I-10 widening project, the Paso del Norte Community Foundation is partnering with the City of El Paso to make plans for the building of a deck park on top of the highway near downtown, using Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park as an example. Wright said the agency received requests to design the highway so that it “does not preclude a future deck plaza.”

The elevated-park proposal won a $900,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to pay for a feasibility study. The park could also apply for funds under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s Reconnecting Communities program, which aims to “reconnect communities that are cut off from opportunity and burdened by past transportation infrastructure decisions.” The deck park would likely need to find additional financial support, possibly from the El Paso Metropolitan Planning Organization, the private sector, or local charities like the Paso del Norte Community Foundation.

During a recent meeting to discuss plans for the park, Paso del Norte Community Foundation CEO Tracy Yellen displayed posters detailing a range of options for how the deck park might look. In one section of the display, stakeholders had placed green and red stickers on the placards—green to mark amenities they liked and red to mark ones they disliked. Red stickers clustered around an image of desert plants, while green stickers crowded the photos of event spaces. Yellen said the stickers would be “directional” and not definitive—the desert plants let out a sigh of relief.

A group of advocates who opposed the highway-widening plans, including Brandon Carrillo, pressed Yellen with respectful but pointed questions. “Is this a done deal?” No. “Will you use native plants?” Yes. “Have you looked at the health impact of this?” Yes. “Will you ask TxDOT to not to add any lanes to the freeway?” We haven’t taken a position.

“I do think people feel like this is really a real opportunity, and TxDOT doesn’t have to do this or allow for it,” Yellen told me. “They could conceivably build the highway and we would have no additional amenities.” She added that the deck park is still possible without the widening.

Opponents of the highway project expressed ambivalence about the park proposal. “There’s a document out there somewhere where TxDOT has said, ‘The only way we’re going to build the supports is if we get to widen it,’ ” Scott White, policy director with Velo Paso Bicycle-Pedestrian Coalition, told me. “There shouldn’t be any kind of condition there.”

Steve Ortega, a fifth-generation El Pasoan who previously served as a city council member and whose family has maintained roots in neighborhoods near I-10 for decades, called the deck park an important opportunity. “The highway was a necessary piece of infrastructure for this community and communities across the country, but I’d be lying if I told you that it did not bifurcate Sunset Heights from downtown,” he said, referencing the historic neighborhood that was cut off from downtown when I-10 was completed there in the late sixties.

Ortega doesn’t believe that adding lanes will add cars to the road. “When people talk about ‘Oh, this is inducing traffic use,’ that’s not true,” he said. In his view, referring to the I-10 project as a “highway widening” is a “misnomer” because the additional lanes would only make the downtown portion equal in width to other stretches of the interstate. (TxDOT consistently uses “widening” in its language about the project.) Ortega echoed Calvo’s sentiment that El Paso tends to get passed over for bigger projects. “TxDOT is not bending over backwards to spend money in El Paso,” he said.

Despite the efforts of groups opposing new highway construction plans, the project appears likely to move forward in some form. Brandon Carrillo said that during a TxDOT public meeting, there was no option to not build among the design proposals, even though he was told the no-build is always on the table. An email from Wright suggested that the I-10 widening, which is not yet fully funded, would move forward in one way or another in 2024. “The no-build does not meet the purpose and need,” she wrote.

But for residents like Bob Storch, modernizing the highway in its existing configuration is the best path forward. “It does need to probably be repaved and rebuilt, but I’m saying if it’s in imminent danger of failing, then let’s fix it . . . the way it is,” Storch said.

- More About:

- El Paso