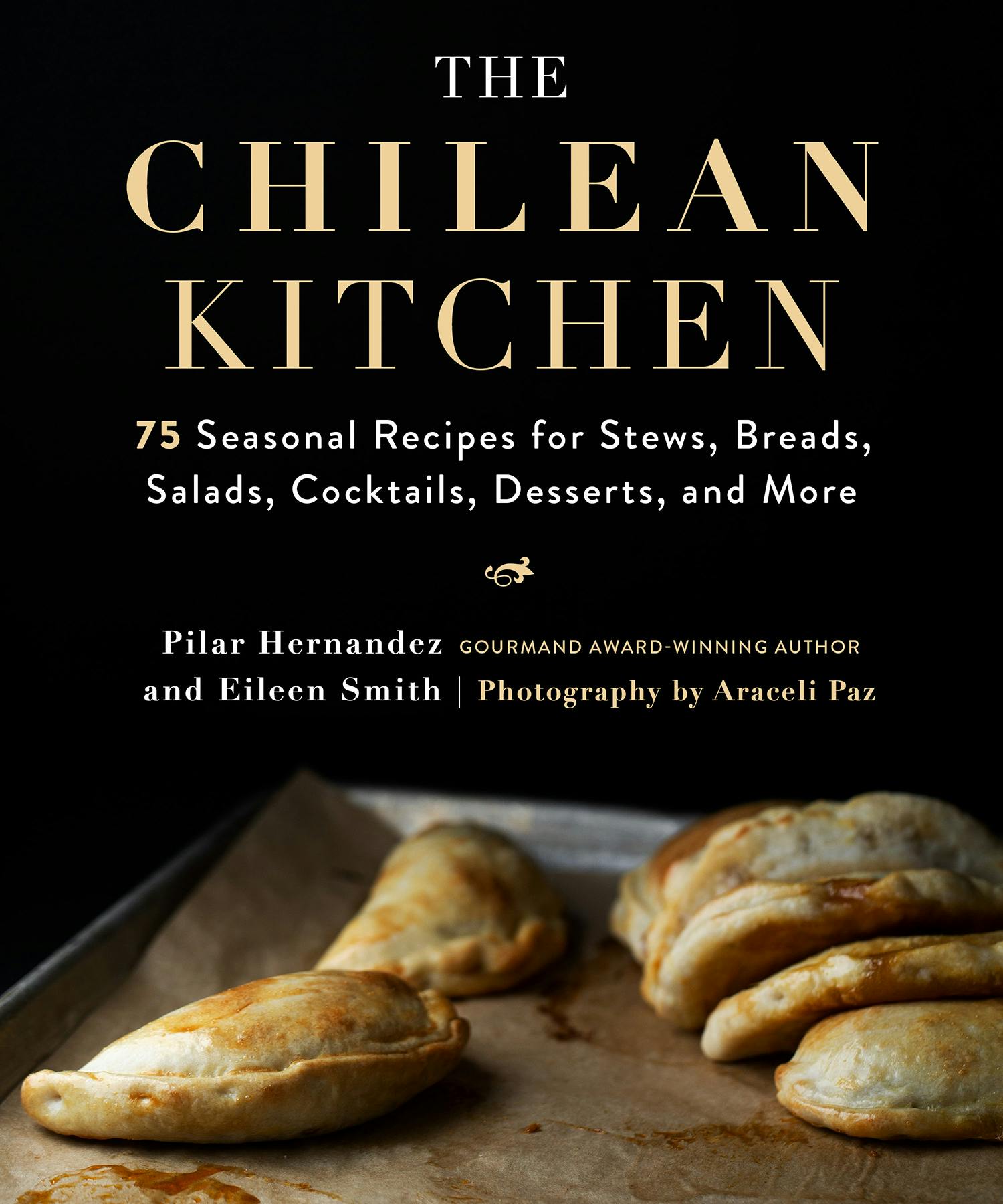

Growing up in Chile under a dictatorship, Pilar Hernandez knew only home cooking as a child—because of curfews, she and her family stayed home at night. She went to medical school in her home country but then soon moved to Houston, where she rekindled her love for her childhood cuisine. While teaching herself to re-create the foods she grew up eating using ingredients available in the United States, she launched a bilingual food blog documenting the process and the resulting recipes. She has since become an urban gardening advocate, a photographer, and a mom. And now, as of October, she is a coauthor, along with Eileen Smith, of one of the only cookbooks on Chilean food available in English: The Chilean Kitchen: 75 Seasonal Recipes for Stews, Breads, Salads, Cocktails, Desserts, and More (Skyhorse, $25).

I spoke with Hernandez about the difficulties she had at first in finding Chilean flavors in Texas supermarkets, how she re-creates the flavor of ají peppers in her garden, and why the welcoming immigrant community in Houston was vital to her journey to becoming a cookbook author. She also shares her recipe for alfajores, a sweet Chilean treat, just in time for Christmas.

Texas Monthly: Tell me about your background—did you grow up in a family of cooks?

Pilar Hernandez: I grew up in Chile in a small city, sixty miles south from the capital, Santiago. I grew up in a family that was super into food, without being foodies, because really that was not a thing. I was born when we were still under dictatorship. There were no restaurants for the longest time. When democracy came back, I was thirteen. [But until then], for the longest time we had a curfew. Really, all of my family, all our life was inside the home. So, home cooking was just what it was. There were no other options at all. My grandfather would fish, and my grandmother would take whatever he brought home and cook it. All our family celebrations were around traditional Chilean food. We have a bunch of family traditions.

TM: What kind of traditions?

PH: In my family, we will spend Christmas together and then everyone will go home. My uncles and aunts live in cities close to where my grandparents were, an hour away, so my grandparents’ house was the reunion place. And then, everyone will come back for New Year’s and on January 1st, we always, always, always do humitas. They are like tamales, but you use fresh corn. It’s very laborious. You need to shuck the corn, select the leaves from the corn, then do the paste, and then cook the paste, and then form them into humitas, and then cook. It’s a whole day. We’ll do humitas and [beef and corn casserole] pastel de choclo. That is another very traditional Chilean dish. We use the same corn for both. I thought everyone did that. And now I realize, no, it was just my family!

TM: How did you wind up in Houston?

PH: My mom was a single mom and had a college degree. She was very adamant that I needed to be very studious, go to college, and get a good profession. I went to medical school, and I met my husband there. When we finished medical school, we got married. We came to Houston in 2003. I was fresh out of medical school and he was doing his master’s. We were coming for two years and I was like, great, because I can have a baby, I can stay with the baby for a while, and then we will go back. [But] we never left.

TM: And how did you end up writing about Chilean food? Were you always interested in cooking?

PH: My husband and I are both into food, so we were just going to all the places [in Houston], because everything was new. In Chile, there were not many different cuisines. You would have Peruvian food, and then Japanese food got really big. So, coming here to Houston and seeing all of the variety, we spent, I’m not kidding you, two years just eating out, whatever it was we could afford, because we were on a student budget. But after a while, we looked at each other and it was like, “Oh my God, I want to get Chilean food, and there is no Chilean restaurant here.”

TM: Out of necessity, we started cooking. I started calling my grandma, calling my mom, and trying to figure it out. I would go with my list to a supermarket and just try different brands, because I didn’t have any know-how that my mom could give me. You know when your mom says, “Oh, no, no, no, you need to get the red can because otherwise it’s not going to be good.” I didn’t have any of that because my mom had never been to the U.S. That’s why I started a food blog, because I needed to keep a record of what I was using to adapt my family recipes.

PH: It was a personal project at this point. I have all of these flavors and memories in my brain. I really knew what I wanted the food to taste like, but I needed to discover how to get there with the U.S. ingredients. At some point, I was like, “I love this. I really like it. It’s creative.” Developing recipes, for me at least, is very close to being a researcher. I used my scientific brain for that. I stayed with it, and at some point I was like, “I know there is not a Chilean cookbook in the market. I want to do it.”

TM: I know that you’re a gardener. You were talking about how you had trouble finding ingredients at the store. Do you also grow anything in your garden that’s specific to Chilean food?

PH: I always try to grow a sweet pepper and a hot one together, side by side, because they mix, so they get mildly hot. The sweet gets a little hotter. That’s really the flavor of the traditional ají style. It’s the fresh chile that we really use in all the salads and sandwiches and stuff like that. That’s one of the things that is really easy to grow. When you have figured out the varieties of pepper and how to do it, you get almost the same flavor.

TM: What something you wish people in the U.S. knew about Chilean food?

PH: I wish they knew that we don’t have tortillas. It’s the most typical mistake. We’re so far away from Mexico, people! No, there are no tortillas down there. And the other thing is that our food is not spicy at all. It’s very mild. Chile, the name of the country, comes from indigenous words that don’t have anything to do with food.

TM: If people are new to Chilean food, what recipes would you recommend they start with?

PH: The tortilla de zanahoria—the carrot frittata—because it’s so simple. The way that you cut the carrots for that recipe, and then mix it with the parsley—these two flavors together, it’s not something that you usually have here in the U.S. They go so well together. I feel like it would be like opening a window to how use vegetables together to complement each other. But people have told me what they have cooked first are the broccoli fritters, the fritos de brócoli. They love that recipe. A bunch of people have also done the chickpea soup, crema de garbanzos. I do like these two recipes. I also like that they are vegetable forward, because I feel that most people maybe have an idea that in Chile we eat a lot of beef, and that’s true for Argentina, but Chile was a poor country for the longest time. Beef was always very expensive. It was extremely rare that you will have a steak. I always tell my friends, it’s a very easy food to feel familiar with. It doesn’t challenge you. I feel it could get into your regular rotation easily.

TM: Is there any good Chilean food in Houston these days? For a while, there was one we really liked. Even before COVID, this restaurant was open two or three years and then it closed. There’s only about three thousand Chileans living in Houston.

PH: I do want to say, though, that if I had moved to a different city in the U.S., I would’ve not ended up doing the book. There is this thing about Houston, that people are so curious about other people’s stories. It’s really a city of immigrants. Every time that I talk to people about what I do, so many people have been like, “Tell me more.” It’s always been such a welcoming city. I love that, and it gave me a lot of confidence to keep cooking more and trying to introduce more people. People are curious about it, and they want to know the story behind the dishes, or the vegetables. Here in Houston, everyone, they reminisce about something. I think we all get to share these peeks into other worlds. I love that. I always felt very welcomed here.

Alfajores

To know and love Chilean repostería (sweet treats) is to embrace manjar. Everything from the Torta Mil Hojas/Dulce de Leche Thousand-Layer Cake, to cachitos (filled pastry “horns”) can have manjar in it, and manjar is used to flavor ice cream and milk or simply spread on bread. But one of the quintessential ways to enjoy manjar is sandwiched between two thin round cookies, which we call an alfajor. The name alfajor derives, like many Spanish words beginning with al-, from Arabic, and in many countries, it takes different forms. Here the cookie is sturdy and thin. Other versions may be filled with a dark sugary confection studded with walnuts, or use the less-commonly found manjar blanco. People don’t often make alfajores at home, but when they do, they generally buy manjar (or dulce de leche, as it is known in Argentina) from the supermarket. We’re partial to the Chilean name manjar, a word also used to mean “nectar” in the expression el manjar de las dioses (nectar of the gods). They’re a popular roadside snack in Chile, especially between Santiago and the coast.

Makes 16.

2 cups all-purpose flour

Pinch of salt

3 egg yolks

5 tablespoons whole milk

1 teaspoon apple cider vinegar

1 tablespoon unsalted butter, melted

1 (13.4-ounce) can dulce de leche

1 cup unsweetened shredded coconut

- Place the flour and salt in a bowl. Mix.

- Add the egg yolks and work with a fork until crumbs form.

- Add the milk, vinegar, and butter. Keep working with the fork until the dough starts coming together. Knead by hand and add water by the teaspoon if needed. The resulting dough should be soft.

- Knead for 10 minutes or until the dough feels elastic. Wrap in plastic wrap and refrigerate a minimum of 2 hours, or overnight.

- Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

- Roll the dough out on a floured counter until it is very thin, almost translucent. Cut with a 3-inch round cutter. Lay on an unlined baking sheet. Prick each cookie 3 times with a fork.

- Bake 12 minutes or until golden. Remove to a cooling rack.

- Just before eating the cookies, spread one with a tablespoon or more of dulce de leche and press the other cookie on top until the dulce de leche comes close to the edge.

- Spread a thin layer of dulce de leche around the rim of the cookie and then roll in coconut.

- You can store the cookies, unfilled, in an airtight container for 10 days.

Excerpted with permission from The Chilean Kitchen by Pilar Hernandez and Eileen Smith. Skyhorse Publishing, 2020. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Recipes

- Texas Cookbooks