The biggest problem with living in a historic house is time—not just coping with the natural aging process of an elderly building but learning to live with architectural patterns that were made to fit the lifestyle of a different era.

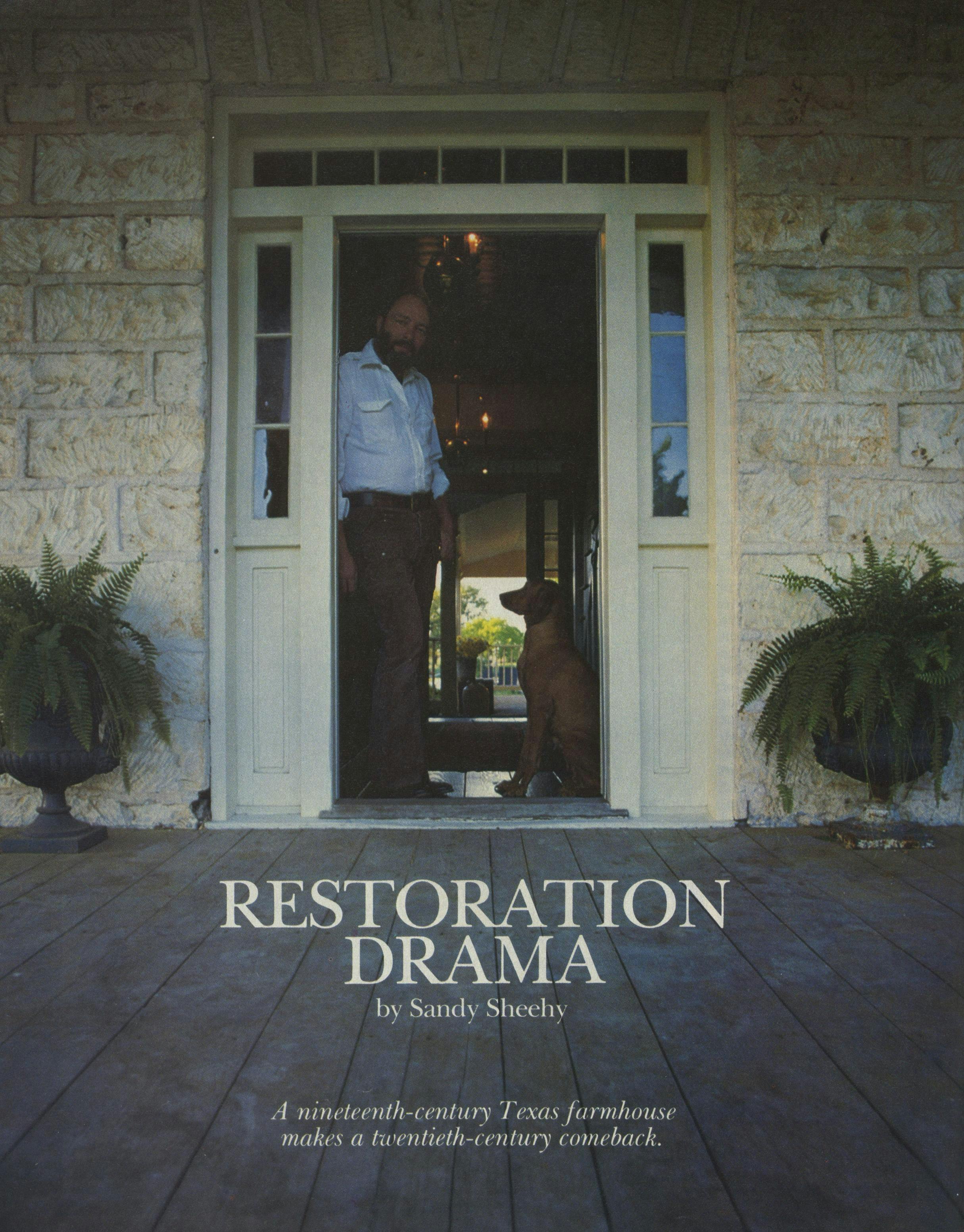

Restoration architect Wayne Bell has had to deal with both problems in the ten years he has spent renovating his handsome 107-year-old Central Texas farmhouse. Located between Round Rock and Taylor, half an hour northeast of Austin, the historic Merrell House is a rough-hewn limestone building of pleasingly simple lines. Except where the Taylor highway marks the edge of the front yard, the setting is pastoral, much the way it might have been when the builder of the house, Captain Nelson Merrell, lived there.

Ample verandas run the width of the front of the house and are connected to the L-shaped back porch by a traditional broad central hall, which draws air through the house when the front and back doors are opened. The only incongruity in the building’s rural facade is the enclosed cupola topped by a widow’s walk (a sort of lookout point on the roof), a feature more often seen in coastal houses, particularly those of the Eastern U.S.

The land on which the Merrell House stands has shrunk over the decades from a large farm to five and a half acres, but a turn-of-the-century barn still stands, providing storage and work space and a small upstairs apartment. The barn shares the property with a double geodesic-dome greenhouse, a ten-by-fifty-foot heated pool (for serious lap swimming), and a flower garden. There’s also a pen for Barbados sheep, kennels for two vizsla hounds, and a coop full of Araucana chickens (a Peruvian breed that lays blue eggs). Whatever the Merrell House might have been, today it’s the home of a gentleman farmer.

![The five-room farmhouse was completed on Christmas Day 1870 by Captain Nelson Merrell, a Yankee soldier of fortune who came to Texas in the 1830s. According to available documents, the contractor was a Mr. Smith. In return for his labor, the captain paid Smith in "alcohole [sic], gold, and pork" to the probable amount of three or four thousand dollars in 1870 currency.](https://img.texasmonthly.com/1977/05/Restoration-Drama-0004.jpg?auto=compress&crop=faces&fit=fit&fm=pjpg&ixlib=php-3.3.1&q=45)

Bell and Joe Colwell, an economics professor at Southwestern University, have owned the house jointly since 1966, when they bought it for $21,000. What followed was ten years of careful planning and hard work, much of which Bell and Colwell did themselves. “The whole project has cost us somewhere under $100,000 in materials and contracted labor,” says Bell. Considering that they were offered more than $250,000 for the house last year, it has been a good investment.

In both of his positions (senior partner in the Austin architectural restoration firm of Bell, Klein, and Hoffman and associate professor of architecture and American Studies at the University of Texas), Bell has given much thought to the philosophy of restoration. “One thing that frightens people away from living in old houses is the feeling that they have to be true to the past,” he says. “They feel a moral obligation to put a building back the way it was and then try to live in it. But you can be sympathetic to a house without being completely honest to it.” According to Bell, there’s only one rule: Don’t do anything irreversible.

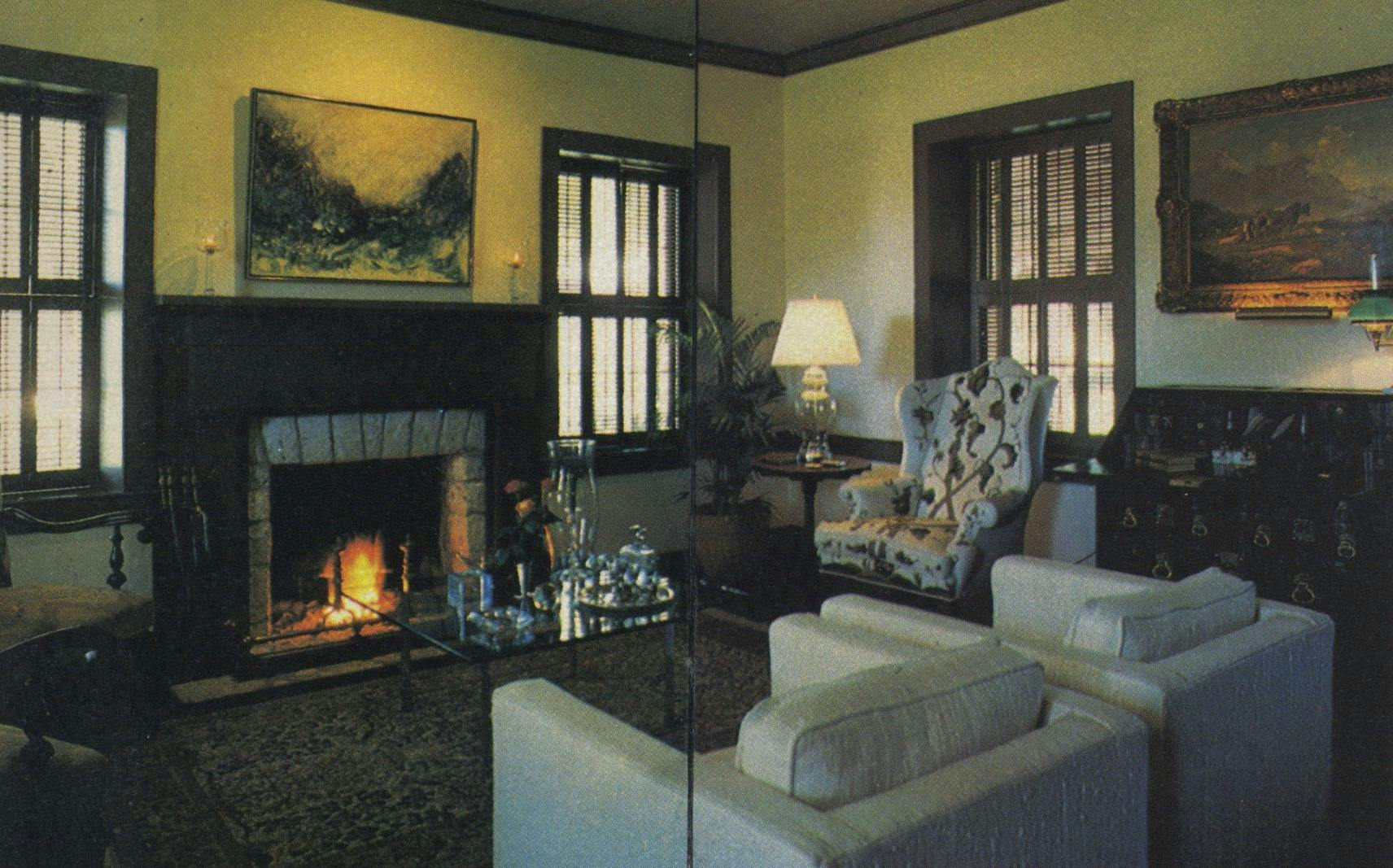

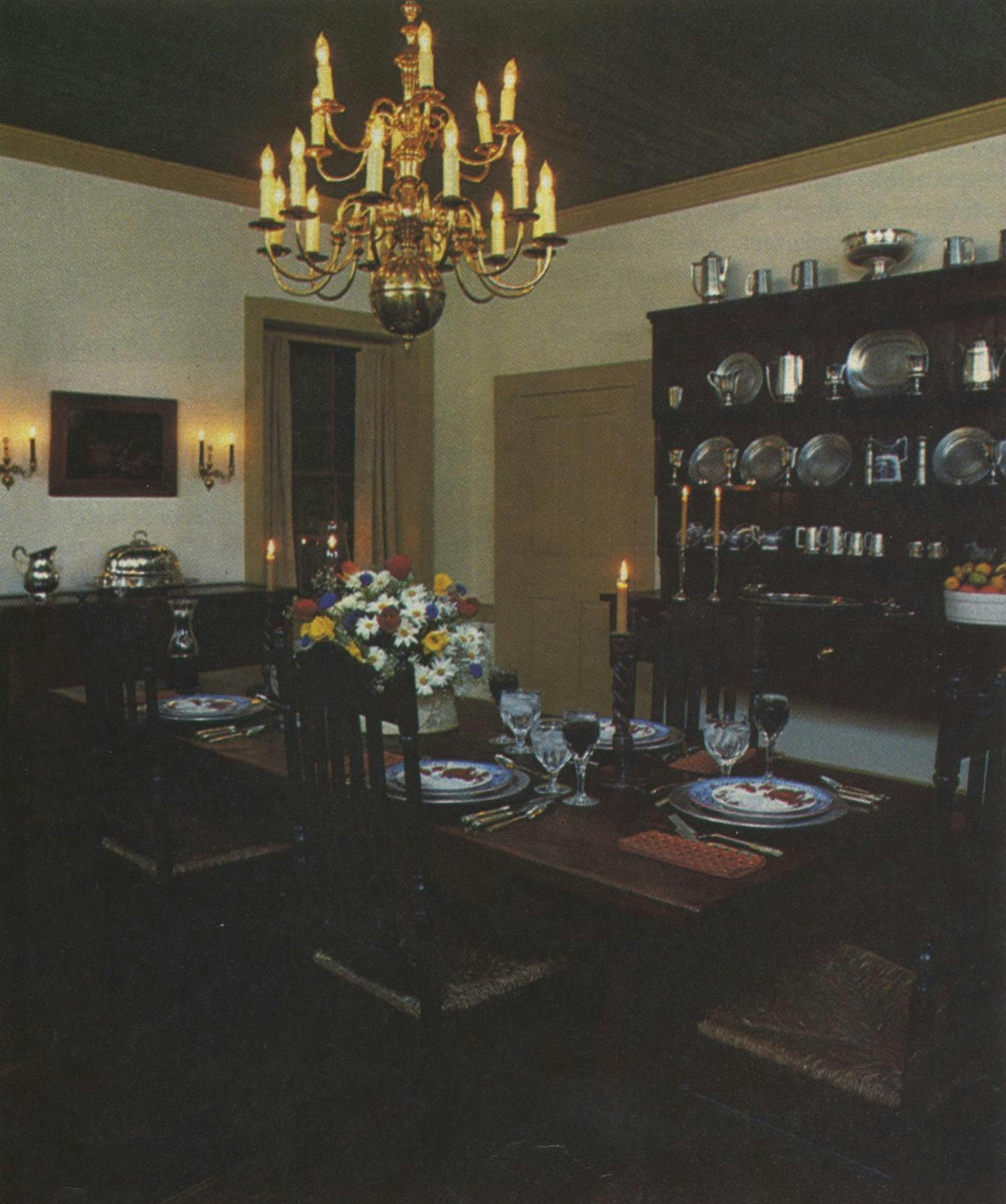

The exterior appearance of the Merrell House is as it was in the nineteenth century, but the interior (which is open to the public only during civic group tours) reflects the twentieth-century tastes and lifestyle of the owners.

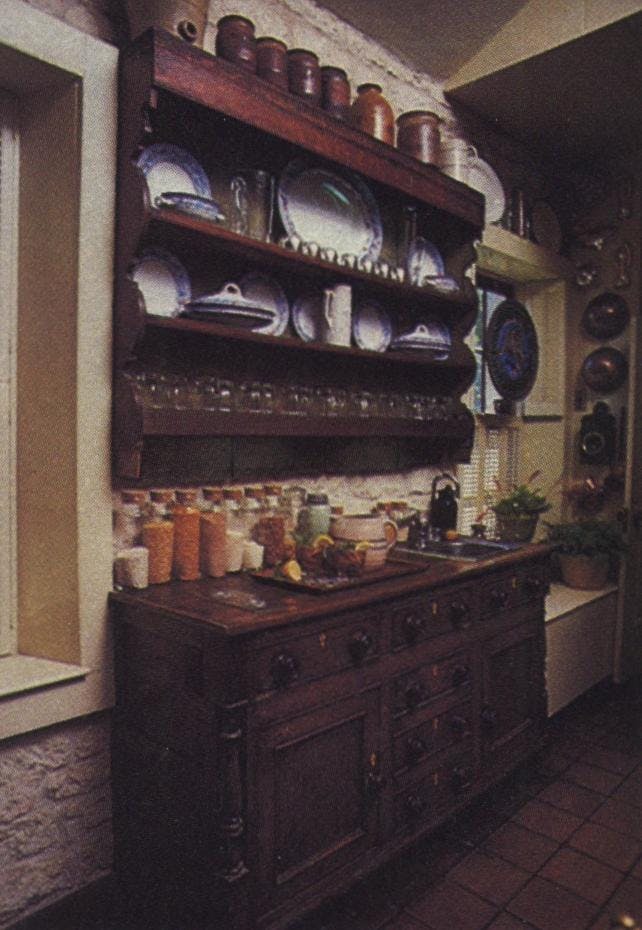

Bell has not hesitated to add closets, which were as unheard of as indoor plumbing at the time the house was built. Concealing contemporary conveniences, like air conditioning and security systems, was one of the house’s major architectural challenges, one which Bell met with a combination of skill and resignation. Some things just couldn’t be completely hidden. “I’ve tried to make it a house, not a museum,” explains Bell. “You can live with the nineteenth century without having to live in it.”

The headaches involved with renovating the Merrell House often proved more serious than merely concealing air vents. For one thing, the building had settled considerably with age. The floors in each room had to be leveled and supported on floating piers. All the windows had to be taken out, cleaned, and repainted; and the stone lintels over the windows, doors, and fireplaces were removed and remortared. To prevent drafts in the high-ceilinged rooms, several petroleum-sealant weatherproofings were necessary, both inside and out, and storm windows were also installed. The pine floors had to be replaced, and every interior wall was replastered except where the stone was left exposed in the kitchen-informal living room.

Knowing what to keep and what to tear out is one of the trickiest parts of preservation, and Bell suggests contacting an architect with preservation experience. Architects will usually consult for considerably less than they charge to do a whole design.

Most major Texas cities have at least one architectural firm involved in historical preservation. The Texas Historical Commission mentions Eugene George and Coffee and Crier (as well as Bell, Klein, and Hoffman) in Austin; Ford, Powell, and Carson in San Antonio; Beran and Shelmire and James L. Hendricks in Dallas; Graham Luhn and James A. Bishop in Houston; Willard Robinson in Lubbock; Duffy Stanley and E. W. Carroll in El Paso; James Rome in Corpus Christi; James D. Tittle and Gary Pullin in Abilene; and Raiford Stripling in San Augustine.

Money, formerly the chief obstacle to restoring an older house, has loosened up considerably in the last ten years, as savings and loan companies come to see an increasing resale value in older properties.

But in the end, money is only the most negotiable of the rewards of restoring an old house. The most tangible reward, and the most lasting, is the pleasure of living comfortably with the past while preserving it for the future.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Architecture