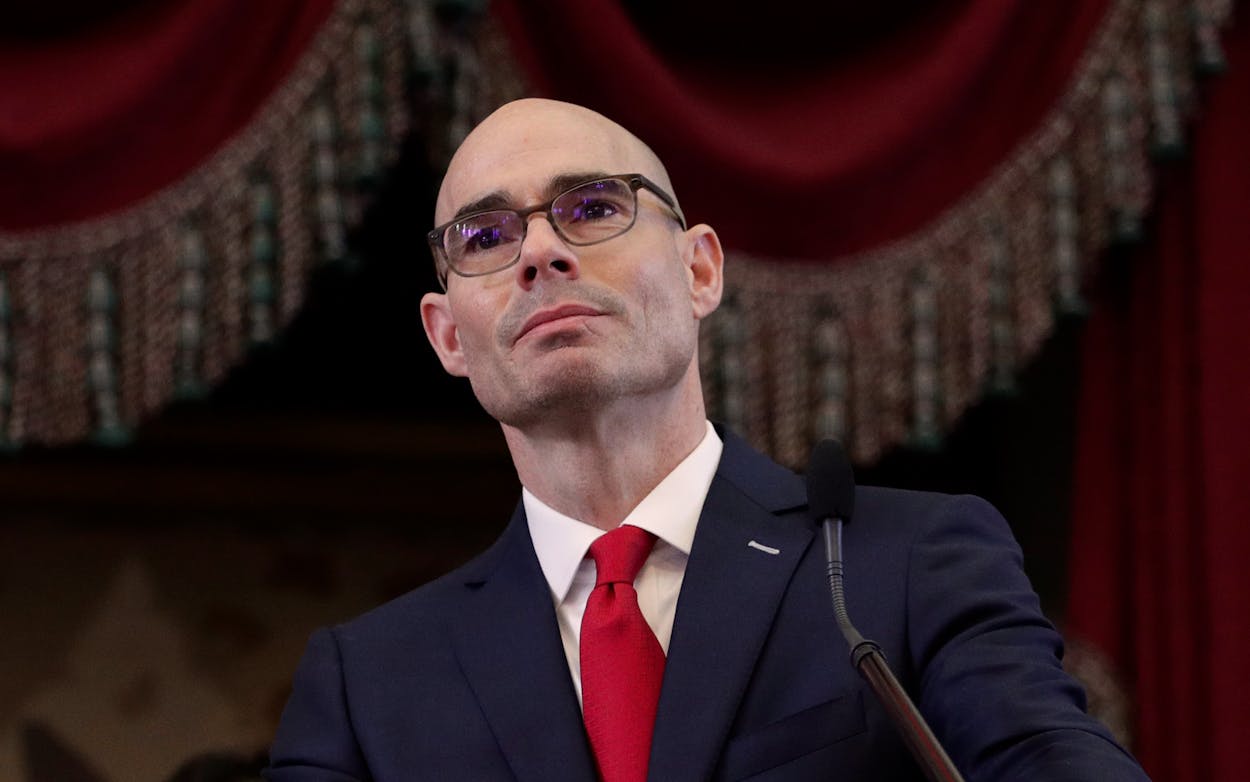

As far as speaker scandals go, L’affaire de Dennis Bonnen is missing some of the luster of past episodes. The controversy lacks the lurid appeal of that time in the nineties when Speaker Gib Lewis took a lobby-funded trip to a Mexican resort accompanied by some well-connected attorneys who brought along a stripper named Chrissee. Also absent is the avarice of Speaker Gus Mutscher who traded favorable legislation for a financial interest in a bank as part of the 1971 Sharpstown stock fraud scandal. And the importance of the Bonnen affair has been diminished on Twitter with the hashtag #Bonnghazi, putting the scandal in the category of a here today/gone tomorrow controversy.

Still, this growing scandal is about much more than palace intrigue. Fundamentally, it concerns unethical, possibly criminal, behavior on the part of the speaker, and a long history of state legislators trying to put themselves above the law.

Judging from Michael Quinn Sullivan’s accounts and a partial transcript of his tape of the June meeting with Bonnen, there are serious questions about whether the speaker violated both campaign finance and ethics laws—including bribery. Bonnen appears to have offered to take an official action if Sullivan would use his political organization to go after ten legislators whom Bonnen found objectionable while avoiding attacks on Bonnen.

The stakes are high, far more than just whether Bonnen can politically survive as speaker. At least nine state campaign finance laws in question are Class A misdemeanors, each punishable by a fine of up to $4,000 and a year in county jail. A bribery conviction is a second-degree felony, punishable by two to twenty years in prison. Bonnen has denied offering a bribe to Sullivan or any wrongdoing, although he offered an apology to his fellow lawmakers.

This scandal grew out of politics, pure and simple. Sullivan and his Empower Texans group—largely financed by fundamentalist Christian oilmen from West Texas—spent much of this decade trying to defeat Republican allies of former Speaker Joe Straus in GOP primary races.

At the June meeting, Bonnen asked Sullivan to not spend against him in the Republican primary. “I would prefer you not hammer me every chance you get. But as long as you don’t spend against me,” Bonnen said at one point, according to a partial transcript of Sullivan’s recording of the meeting published on Direct Action Texas by a Sullivan ally. Bonnen and Representative Dustin Burrows, a Bonnen lieutenant, also suggested the names of incumbent House members that Sullivan’s group might want to defeat. At one point, Bonnen said, “All right, so we are clear the money is the issue and back down on the rhetoric.” The trade-off: the propaganda arm of Empower Texans—Texas Scorecard—would receive media credentials that would grant Sullivan’s employees to access the Texas House floor. The media credentials component is important because it would give Sullivan’s operatives direct access to lawmakers when they are actually voting on legislation. “We can make this work. I’ll put you guys on the floor next session,” Bonnen says.

Aside from the quid pro quo aspect of the scandal, exchanging money in the Capitol or directing expenditures from a Capitol office has been a Class A misdemeanor ever since the Legislature reacted to a 1989 public outcry over the late chicken producer Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim handing out $10,000 checks to nine senators in the Senate chamber during a hearing on workers compensation reform.

Besides the issue of whether there was bribery involved, there are also potential election law crimes, including not disclosing the source of campaign contributions directed by Bonnen. The Texas Democratic Party filed a lawsuit against Sullivan on Thursday, alleging nine different potential criminal violations of the Texas Election Code, each a Class A misdemeanor. The lawsuit seeks to preserve evidence and damages of $100,000.

The Texas Legislature made dramatic changes in 2015 to how public corruption cases are handled in Texas. The Travis County public integrity unit no longer has jurisdiction over elected officials at the Capitol. Potential criminal cases must be investigated first by the Texas Rangers public integrity unit.

The House General Investigating Committee on Monday voted 5-0 to have the Rangers investigate the Bonnen/Sullivan affair and report back to the committee when the investigation is complete. Chairman Morgan Meyer read a statement that the report to the committee does not preclude the Rangers from reporting to other appropriate authorities.

If the Rangers decide further action is warranted, the case is referred to the home county of the public official. That means any corruption charges against Bonnen would have to be brought by the Brazoria County DA. For Burrows, it would be the Lubbock County DA. Travis County would retain jurisdiction only over Sullivan. In cases of multiple jurisdiction, the Texas attorney general’s office can take charge.

Funnily enough, Attorney General Ken Paxton is under indictment on securities fraud charges in his home territory of Collin County. Paxton is accused of failing to register as a securities agent as part of his private law practice. He claims he is innocent and that the case is politically motivated. Paxton counts among his allies the funders of Empower Texans. (The plot always seems to thicken in this scandal.)

The House General Investigating Committee also has the power to completely remove the specter of criminal prosecution from Bonnen and Sullivan, though that seems unlikely after Monday’s hearing. The Texas Government Code states in Section 301.025 that no person has a privilege to refuse testimony “even if the person claims that the testimony or document may incriminate him.” The statute goes on to state that if the person claims the potential of self-incrimination, “the person may not be indicted or prosecuted for any transaction, matter, or thing about which the person truthfully testified or produced evidence.”

It’s the legislative equivalent of a Get Out of Jail Free card—maybe. Several lawyers I spoke to on background said the law is difficult to interpret because no court has considered the matter. The attorneys said the statute may nonetheless require the witness to testify fully, and the witness might be the subject of a criminal case for any matter left out.

I searched internet newspaper databases going back to the 1950s and could not find an instance when it applied to a legislative case—even when the House General Investigating Committee looked into the Sharpstown scandal in 1971. During the 1950s and 1960s, the House committee offered immunity to witnesses in cases involving gambling corruption and bribery at the Veterans Land Board and the Texas Railroad Commission, but the witnesses invoked their constitutional rights and refused to testify. The most recent case I could find was from 1980 when a San Antonio College official who already had been convicted for taking kickbacks received immunity from the committee to discuss possible crimes at the school.

For Bonnen to receive immunity, he apparently would have to fully and completely admit to everything on Sullivan’s tape. That might even be worse than a criminal case because it would pressure lawmakers to defend their vote for Bonnen in next year’s elections. At the moment, many legislators appear to be waiting to see how this all shakes out. Will this affair be the summer scandal that vanishes with Labor Day? I doubt it. I’m guessing it will drag into the fall like a wound that festers.

This story was updated at noon on August 12.