There is something particularly forlorn about the Texas suburb. In the opening frames of Richard Linklater’s SubUrbia, released 25 years ago this month, the camera drifts slowly past subdivisions and superstores plopped dispassionately onto the rolling Texas expanse. This erstwhile frontier, where mavericks and rebels came to wrest their fortunes out of the ground, is a blur of McDonalds drive-throughs and beige, boxy McMansions. It is uniquely dispiriting.

SubUrbia is one of Linklater’s least-loved films, consistently ranked near the bottom in Internet listicles appraising the Austin director’s career. And at least some of that is because it’s kind of a drag. Compared with the rest of what Linklater would, in 1997, call his “hangin’ out quintet”—an oeuvre that included Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise, and his micro-budget debut, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books—SubUrbia is certainly less romantic or nostalgic about the dreamy idleness of youth. At the time, Linklater even told the Austin Chronicle that SubUrbia marked “the nail in the coffin” for those kinds of stories. It was a bold statement that, thankfully, didn’t prove to be true.

SubUrbia marked a turning point for Linklater, a moment when the hazy rambles of Slacker, Dazed et al. gave way to something more acrid and claustrophobic. True, it’s often way less fun to watch. But SubUrbia provides a fascinating countermelody to Linklater’s freedom-rock choogle. In its own melancholy way, it captures something equally authentic about those alienated years between high school and adulthood, particularly if you spent them stuck inside the drab Texas hinterlands.

Similar to Linklater’s other “hangin’ out” movies, SubUrbia takes place over the course of a single night. It similarly finds its characters at a crossroads. In SubUrbia, they’re literally at “The Corner,” a convenience store that’s situated on an anonymous intersection within the fictional Texas town of Burnfield (in reality, Austin’s South First Street and Stassney Lane). At this symbolic nexus, various late-teen/early-twentysomething kids meet up to drink beer, eat pizza, and watch the streetlights change, all while they pontificate about the things they want to do with their lives.

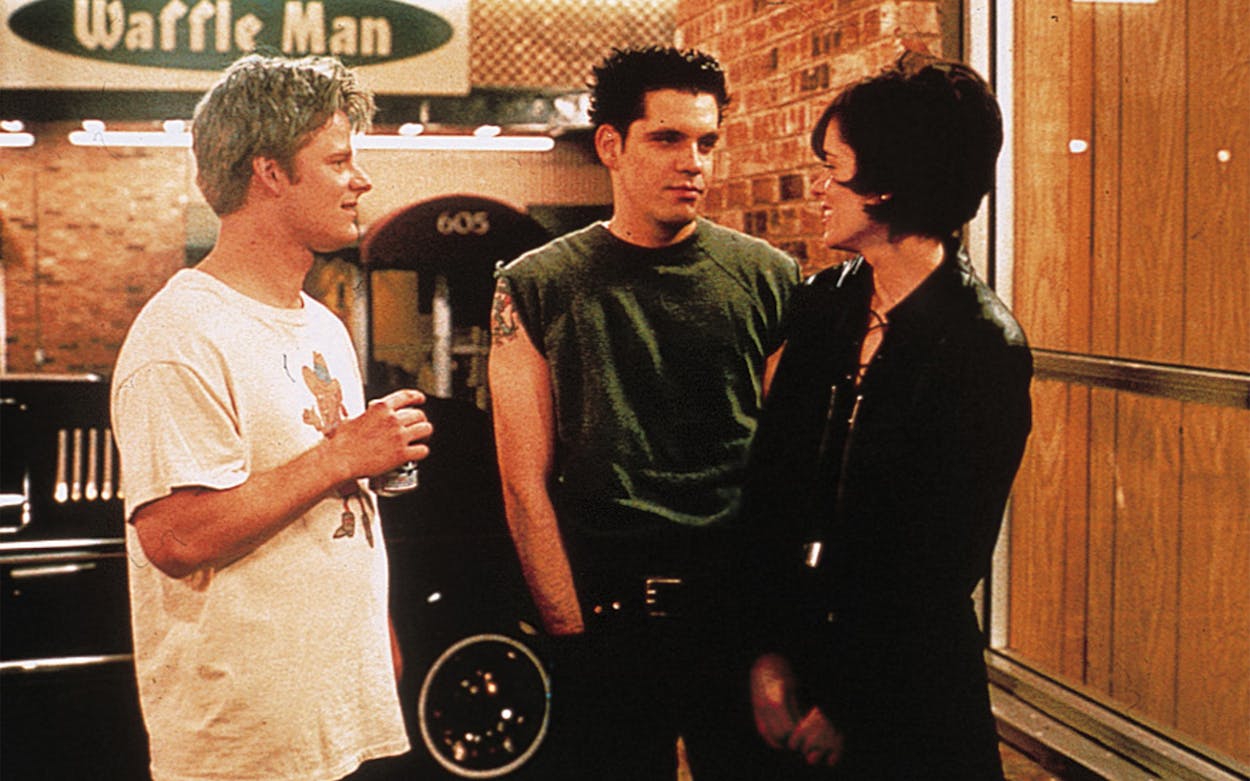

Jeff (Giovanni Ribisi) is an aspiring writer and inveterate complainer. Tim (Nicky Katt) is an Air Force washout who’s fueled by alcohol and rage. Buff (Steve Zahn) is their hornball jester, craving only hedonistic pleasures and attention. They’re joined by Jeff’s girlfriend, Sooze (Amie Carey), a sweet-natured artist in Riot Grrrl armor, and her shy, willowy friend, Bee-Bee (Dina Spybey), who’s still fragile from a recent stint in rehab. SubUrbia finds them assembling for another parking lot symposium that also promises a surprise appearance from Pony (Jayce Bartok), a former classmate turned newly minted rock star. When Pony pulls up to the corner in his limousine, big-city publicist (Parker Posey) in tow, he kicks off a whirlwind of drunken arguments and minor epiphanies.

Every character here seems damaged or deluded in some way; they’re all self-involved and kind of annoying. Jeff waxes pompously about standing for “truth” and his desire to “break new ground,” but he repeatedly devolves into bitter self-pity. Buff and Tim are rude, sexist bullies who also subject the convenience store’s harried Pakistani owners (Ajay Naidu and Samia Shoaib) to threats and racist taunts. Sooze proves to be the most affable of the bunch, but she’s also the most pretentious. Her feminist performance-art piece—which culminates in tap dancing while she screams, “F— all the men!”—is played for laughs. Pony seems nice enough but he also humblebrags about the tediousness of celebrity life. You wouldn’t necessarily want to be friends with any of them.

This is a departure from Linklater’s other “hangin’ out” films, where even the biggest jerks are allowed a bit of charm. In Dazed and Confused, Slacker, and Before Sunrise, the characters try to hold onto these moments of togetherness, before life pulls them apart. Here that notion just seems pathetic. These characters are all just dragging each other down: Jeff sees Sooze’s plan to attend art school in New York as a betrayal, so he belittles her talents. Tim nurtures Jeff’s apathy so he’ll stay with him, drunk on the corner. Julie Delpy’s character in Before Sunrise posits that, if God truly exists in this world, it must be in the “little space in between” two people. In SubUrbia, that space is a prison.

Notably, SubUrbia marked Linklater’s first time directing someone else’s material—in this case, the stage play of the same title from writer and actor Eric Bogosian (who’s perhaps best known to modern audiences as the menacing loan shark from Uncut Gems). Upon the film’s release, most of the negative reviews declared it a creative mismatch between Bogosian’s contemptuous tone and Linklater’s loose, naturalistic vibe. But that conflict also creates an interesting tension, one that draws out some of the darker themes creeping beneath Linklater’s other movies.

After all, death and violence lurk throughout the deceptively placid Slacker; talk of mass shootings, political assassination, and matricide are all bandied about as casually as the weather. As Linklater pointed out to the Austin Chronicle, there are even “dark shadings” to Dazed and Confused. (“People are beating each other,” he said. “There’s a lot of abuse. It’s sad.”) In what may well be a thesis statement for the career that followed, the main character in It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, played by Linklater himself, kick-starts his aimless wandering by firing a shotgun out of his bedroom window. Linklater’s movies all deal, in some way, with the temporality of life—how we cope, moment to moment, with the inevitable fact that death will burst in with both barrels blasting.

Of course, SubUrbia has a more tragic bent than most of Linklater’s films. Yet it also feels more of a piece with the rest of his work than it is often given credit for. This is particularly true in its sense of place. There’s nothing explicitly “Texan” about SubUrbia, other than a single scene set inside a Whataburger. But through the film’s opening montage alone, Linklater puts SubUrbia in conversation not just with his own movies, but with other films about disaffected dreamers languishing in small Texas towns.

It’s interesting to consider SubUrbia alongside The Last Picture Show, for example, which debuted almost exactly 25 years earlier. Both films are about recent high school graduates confronting and delaying their futures: drinking too much, having furtive sex in the backs of cars, gazing meaningfully at the stoplights and yearning vaguely for escape. In each movie, the recent past hangs heavy over the characters’ lives: Like Sonny Crawford in The Last Picture Show, Suburbia’s Tim is forever being pestered about old defeats on the football field. He even winds up getting arrested by a former teammate. (“You were a shitty lineman, and now you’re a shitty cop,” Tim sneers.)

Meanwhile, everyone is fantasizing about running off to somewhere more exciting, a dream that’s made to seem all the more remote by the vast Texas landscape that surrounds and swallows them. “Everything is flat and empty here. There’s nothing to do,” whines Ellen Burstyn’s Lois in The Last Picture Show, and while she’s talking about her one-street, fifties town of Anarene, the sentiment applies equally to the anonymous stretches of chain restaurants choking SubUrbia’s Burnfield.

In both films, the characters’ ennui and lack of purpose is tied to the slow, generational erosion of their identities as Texans. They’re the descendants of cowboys who traded ranches for ranch-style homes. They’ve won their freedom and comfort, and now they can’t figure out what they’re supposed to do with it.

Yet, just as in all of Linklater’s other films, dawn arrives. Yes, SubUrbia’s kids have problems—“many problems,” as Gene Pitney wails over the opening credits—and right now they all seem melodramatically huge. But they’re also kids. Like so many Linklater characters, their stories end in an ellipsis. As Linklater himself put it to the Chronicle, “I was really f—ed up at twenty, just like they are. You kind of find your footing, make your life, and maybe you can get it together. And I think a large percentage of them will.”

SubUrbia, like the rest of Richard Linklater’s work, grapples with the myriad ways our lives are shaped by where you are now—with the understanding that these moments are fleeting yet significant, and rife with endless possibility. Linklater’s newest film, debuting at this year’s South by Southwest, is the semi-autobiographical Apollo 10 ½, which will find him returning to the Texas suburbs to tell the story of another kid who dreams about the kind of far-off adventure he’s only glimpsed on TV. It’s another fantasy of escape that feels unique to those flat, Texas towns. But in their emptiness, Linklater also sees potential.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Richard Linklater