Let me confess. I have been apostate. I have been known to forget to lug my recyclables out to the alley on recycling day. Worse, I often don’t care, and once even told my wife, “Oh, what the hell. They probably take it to the landfill anyway. Recycling’s just a way for boomers to feel less guilty.”

Oh, the blasphemy! And I have further sinned in my heart by entertaining other dark questions of the lapsed. I’ve wondered why, now that our country has been recycling for more than one hundred years—and does so presently at relatively impressive rates (a third of all trash; half of our paper)—these efforts don’t seem to be making a dent in our environmental woes. And what ever happened to the great garbage crisis, anyway? You know, the scenario ginned up by the media back in the eighties, in which we were about to be buried in our own refuse as Old Testament retribution for our conspicuous consumption? Furthermore, if recycling is such a cure-all, why, when I plug the numbers into my personal carbon footprint calculator, does it produce reductions of less than a tenth of what reinsulating my attic did? Really, why do it?

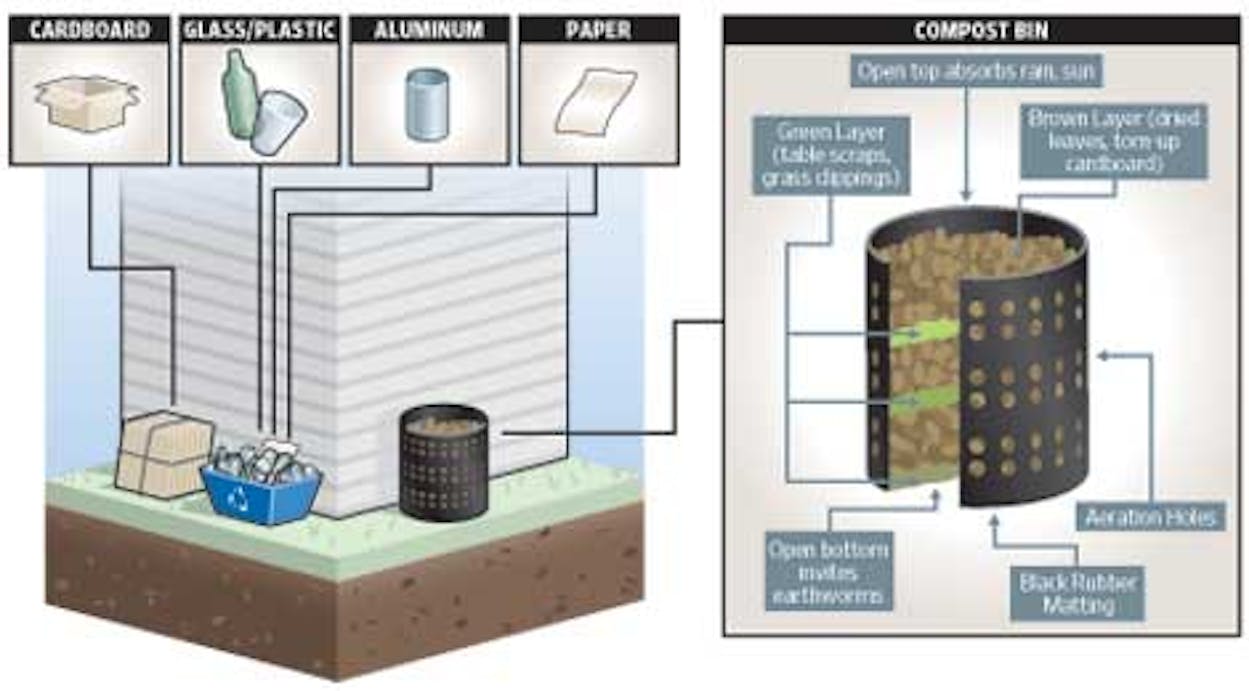

I needed to know if our earliest and most widely embraced sacrament of greening is actually worth it. So I determined to dive into the subject more deeply—as, say, a fallen Catholic might seek answers to his doubts by attending Mass twice a day. Starting in January, I vowed to be earnestly vigilant about my basic recycling, not leaving a shred of newsprint to chance, and to observe its effects on my life. For more than half a year now, my wife and I have been carefully tossing cardboard of various kinds, glass and plastic bottles (including those for detergents and juices), and metal cans into the recycling bin provided by Highland Park, which I have dutifully dragged to the alley each Wednesday morning.

I didn’t stop there. I also researched online and found recycling centers for items that don’t usually get picked up, like Styrofoam. Sometime after Christmas—when we’re bound to have a bunch—I’ll take our packing peanuts to my nearest Mail Boxes Etc. and any big chunks to Foam Fabricators in Keller (other options in Texas include Amazon Forms and Cycled Plastics). Anything hazardous—leftover paints, pool chemicals, batteries, compact fluorescent lightbulbs, cell phones, an old computer—I began stashing in my garage for delivery to the Dallas County Home Chemical Collection Center (you can find centers in your area at tceq.state.tx.us). At the same time, we became more conscious of “source reduction and reuse”: taking cloth bags to the grocery store so that the “paper or plastic” question was moot (both materials clog landfills); converting most of our mail and bills to paperless versions (catalogchoice.org gets you off companies’ lists for almost any catalog for free); using refillable water bottles; and buying concentrates and refills of items such as detergents to reduce packaging.

Finally, in the spring, I took the big leap into what I had always regarded as the black abyss of composting. There was a lot to learn just to get started, but I found two excellent resources at epa.gov/epaoswer/non-hw/composting and compostguide.com. I spent $100 (including shipping) for basic composting tools: a small bucket to place under my sink for food scraps (veggies, crushed eggshells, coffee grounds and filters, but no meats) and a three-by-eleven-foot swath of thick rubber matting that can be made into an expandable cylinder, secured with plastic nuts and bolts. It remains open on the top (to absorb rain and sun) and on the bottom (to invite earthworms) and has holes on the sides for additional aeration.

As recommended by several guides, I placed the cylinder in a somewhat shady alcove near our fence, where it is conveniently out of sight. Here it receives the prescribed amount of warmth from the morning sun but has enough shade to retain moisture (compost piles should be damp, like a well-squeezed sponge). In the cylinder, I’ve begun layering my “green” matter (kitchen scraps and grass clippings that provide nitrogen) with “brown” matter (mainly dried leaves, but also torn-up cardboard and untreated wood, which provide carbon) at a ratio of about 1 part green to 25 parts brown, the ideal for decomposition. This layering is important because even nonmeat leftovers can attract insects or vermin if you don’t cover the scraps with about eight inches of brown matter. When my yard guy does my leaves, I just have him place the bags by the compost bin so that I can add “brown” as needed.

I know: What about the smell? If it begins to stink, which it hasn’t yet, I’ll just till it a bit, which is supposed to eliminate the odor and speed the composting. But I’m not in a hurry for my compost (I don’t need it until next spring), so I plan on a passive approach—let it sit for a year or so before I harvest my first batch. In the meantime, I’ll be eliminating some of the kitchen- and yard-generated waste that goes to landfills; such refuse accounts for nearly 25 percent of U.S. waste flow.

And how have my efforts affected my heretical thinking? Well, recycling is definitely a pain, composting can be icky, and it’s tiresome to try and remember those cloth bags every time. But the simple act of doing all this with such discipline has forced a few useful insights into my forebrain. The first is that of course we can’t expect recycling to have the same green impact as, say, driving hybrid cars—the fossil fuels conserved in each case just don’t compare. But I’ve learned that some kinds of recycling do save. Consider aluminum cans. It takes 95 percent less energy to recycle them than to make them from scratch.

The benefits are not as clear with paper. It’s true that making the recycled variety can use up to 40 percent less energy than milling “virgin” paper, but ironically, it may use more fossil fuels, because the process draws from the basic power grid to operate (regular mills, by contrast, draw primarily from the incineration of wood and paper scraps). Some level of footprint is also left by the transportation involved—true of recycling in general—whether it’s curbside pickup or your driving to a center. But that brings me to my second insight: Complaining that recycling isn’t a greening cure-all is senseless nit-picking. Given the urgency of the global warming crisis, anything that works to even a modest extent should be practiced rigorously. (Note: Recycling guidelines vary by city, so check with your local disposal service before going at it in earnest.) And while it’s certainly true that a lot of people recycle merely for its conscience-soothing effects, I’ve decided there’s nothing wrong with that either. “Do-gooding” is still doing good.

In fact, the redemptive aspect of recycling is actually a useful recruitment tool for prospective greenies who feel the guilt but don’t know where to start. In my case, once I saw how simple it could be, I inevitably found myself taking on more of its rites and rituals. You recycle for a month or so, and next thing you know, you’re picking up compact fluorescent lightbulbs at the store and getting a home audit from your energy provider. It’s infectious, in other words. I also better understood why I was doing it, in a way that another long speech by Al Gore could never have taught me. I once was lost, but ever since I dumped that first potato peel into the compost bin, I am found.

Progress Report:

This month’s effect on my carbon footprint, wallet, and happiness.

Editor’s Note: The compost bin can be found at compostguide.com. Click on “Online Composting Store,” then click on “Standard Compost Bins” on the left of the page. The “Hoop Compost Bin” is the one that Jim bought, which is about $50. The composting bucket for the kitchen scraps adds a bit more, and then shipping gets the total to somewhere just shy of $100.