This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Not much advance notice is given for the big lala dance. Just the usual listing in the Texas Catholic Herald, a few plugs on listener-supported KPFT-FM at three in the morning, and a scattering of thick cardboard posters tacked to poles in the Houston neighborhoods surrounding several Catholic churches. “In Person!” promise the broadsides. “Boozoo Chavis and his Magic Sounds of Louisiana Zydeco Band from Lake Charles will play ‘Paper in My Shoe,’ ‘Uncle Bud,’ ‘Motor Dude Special,’ ‘Dog Hill,’ and other hits at the St. Anne de Beaupre Catholic Church Parish Hall. Cover charge is $7.”

Welcome to the wonderful world of zydeco, the rockingest, grittiest, most danceable and physically alluring indigenous music cranked out in the contiguous 48 states. It is the music of French-speaking blacks whose ancestors learned the language from the Acadians deported from Nova Scotia to the swamps of southwest Louisiana in the eighteenth century. Whites who are descended from that group are known as Cajuns. Black Acadians are Creoles, though they are not to be confused with the citified Creoles of New Orleans. The term “zydeco” comes from a patois pronunciation of “les haricots,” as in the country saying “les haricots sont pas salés” (“The snap beans aren’t salty”). While zydeco bears many similarities to cajun music, it distinguishes itself by being simultaneously down-home and uptown, a sound dominated by French lyrics and an incessant rhythm that is constantly absorbing modern influences. Its signature instrument is the accordion, inevitably accompanied by a hypnotic percussion instrument called a frottoir.

For all those built-in idiosyncracies, zydeco is quite possibly the most popular folk music in America today. Just as the black French population has spread all along the Louisiana and Texas coasts, so too has the music broadened its base of appeal. Remember “Don’t Mess With My Toot Toot,” a number one novelty hit from a couple of years back? That’s zydeco. So is the music of the late Clifton Chenier, the acknowledged original King of Zydeco. Perhaps recently you’ve seen Stanley Dural, a.k.a. Buckwheat, sitting in with Paul Shaffer and the band on Late Night With David Letterman or caught one of his cameos on MTV. Or maybe you’ve heard the zydeco send-up Paul Simon did on his Graceland album that earned his accordion accompanist Rockin’ Dopsie (pronounced “Doop-see”) a Grammy. Or you might have discovered 23-year-old Terrance Simien in the film The Big Easy or in Miller beer commercials. Zydeco is zyde-cool, so trendy a Boston travel agency is running package tours to Louisiana shrines like Slim’s Y Ki Ki in Opelousas and Richard’s in Lawtell. Young people whose cultural familiarity extends no further than which end of a crawfish to eat are starting up zydeco bands of their own across the nation.

In Texas the pure essence of zydeco is preserved in the Saturday night church dance. An important social function in creole communities between Houston and New Orleans, the church dance is the economic mainstay of most zydeco bands and the best way for the nonparishioner to soak up the quirky, hypnotic chanky-chank beat. Dances are normally scheduled every two or three months, and out-of-towners usually must take potluck. Houston, the Los Angeles of Acadiana, to which thousands of Cajuns and Creoles have migrated for work, is the notable exception. With so many Catholic churches whose black parishioners have roots in the bayous, a church dance happens nearly every Saturday night somewhere in the city. At last count, the informal circuit consisted of eleven parishes: St. Anne de Beaupre, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Peter Claver, St. Peter the Apostle, St. Francis Xavier, St. Philip Neri, Our Lady of the Sea, Our Mother of Mercy, St. Gregory the Great, St. Mark the Evangelist, and St. Monica.

Word travels fast. By nine-thirty, the official starting time, more than four hundred people have crowded into St. Anne de Beaupre’s low-ceilinged parish hall. Tables line the walls and fill the back half of the room. The only open area is the dance floor facing the small stage at one end. Every folding chair has been spoken for. Late arrivals are warned at the door that they’ll have to stand or dance.

At the center of all this commotion is Wilson “Boozoo” Chavis, a 58-year-old former horse trainer and veteran zydeco star who has been one hot ticket ever since his decision three years ago to emerge from semiretirement and pick up his accordion again. In that short period Chavis has cut two albums, set tongues clucking with a two-sided X-rated novelty single (“Deacon Jones” backed with “Uncle Bud”), and leapt to the front of the pack of zydeco artists who are striving to claim the title of “king.” He already had experience on his side. Thirty-four years ago Boozoo Chavis made what is regarded as zydeco’s first hit record, “Paper in My Shoe,” a chirpy hole-in-the-sole lament that every zydeco band worth its salt knows by heart. Last year it was audible in the background of the television comedy series Frank’s Place. David Hidalgo of the top-rated rock band Los Lobos calls it one of the ten best songs of all time.

The jut-jawed, baleful-eyed Chavis hasn’t let success go to his head. Onstage he remains an onerous triumph of function over form. The clear plastic apron he wears over his Western shirt and red tie makes him look more like a butcher than a bandleader. The apron keeps sweat from cracking the bellows of his accordion. It also covers the leather belt stamped “Boozoo.”

Switching back and forth from English to French, he sings about stubborn mules, hound dogs (with strikingly accurate hound-dog howls), and a rascal named Joe Pete. On Boozoo’s right, son Wilson Junior, who is called Poncho, a portly, serious young man in a business suit and wing tips, intently twists the knobs of an audio mixing board. Farther right, eldest son Anthony wears jeans, a sport shirt, and a frottoir—a corrugated-metal rub board contoured to his chest—which he strikes with spoon handles on top of the beat. Drummer Rellis Chavis is another offspring. The guitarist and bassist are no relation, though Boozoo tells the crowd, “They’re just like sons—yeah, you right.”

The family spirit pervades the parish hall, where the audience is as much the show as the musicians are. A parade of three-piece suits, miniskirts, formal gowns, starched jeans, and shiny boots passes the bandstand, representing practically every segment and stratum of society. The lady wearing a corsage at the door introduces herself as Mrs. Jane Champagne, the dance promoter. A month’s worth of preparation has produced a long line of ticket buyers. Still, she’s not too busy gatekeeping to sell raffle tickets for a giant decanter of Jack Daniel’s.

Alcohol is not only tolerated at zydeco dances, it is consumed in copious amounts. Jug-size bottles of Crown Royal, Smirnoff, and other liquors are centerpieces on many of the tables. At the back of the hall, several ladies do a land-office business selling beer, soft drinks, huge set-up buckets of ice, and boudin sausage for $1 a link. Chicken-and-sausage gumbo is $3. Despite such volatile ingredients, the presence of friends and kin on consecrated ground tends to keep the lid on any extreme misbehavior.

Up by the bandstand Louis Simien, Jr., 72, a former drummer for Clifton Chenier, eyes Agnes Simien, a young lady who may or may not be a distant relation. There’s no telling from the way she wiggles her posterior as she walks past. Agnes, the younger sister of zydeco luminary Rockin’ Sidney, shows up at the Houston lala dances regularly and is known for arousing the menfolk with her alluring outfits. Tonight her hip shakes are accented by the flimsiest film of leopard-print spandex. “It’s a miracle she can breathe, much less move, without ripping her britches,” Louis Simien observes.

Because St. Anne’s is in an old Polish neighborhood just inside the north loop of inner-city Houston, the crowd is salted with paler faces too: members of the Polish Eagles band on a busman’s holiday; Frank Motley, a machinist, the host of the Telephone Road Show on KPFT-FM, and a zydeco connoisseur; his fiancée, Tracey Baird; and Motley’s father, Johnny, who is a mover and shaker in the Texas Accordion Association. Across the way is a small delegation of preppies awkwardly trying to master the art of grooving. Their efforts go unnoticed by a flashy young dude who wears four diamondlike rings on each hand and continually calls out for “My Toot Toot.” He vies for attention with a mustachioed gentleman with jug ears and a gimme cap standing at the foot of the bandstand, shouting “Et toi” over and over again to no one in particular. A squat elderly man wearing black pinstripes and a porkpie hat cruises nearby, casing the tables for single women.

A naked red light bulb overhead bathes the room in a muted glow. A blue and a white light bulb aimed at the stage illuminate a small crucifix hanging behind the drummer. When there is music, the effect is that of a surreal merry-go-round, as dancers glide in an undulating, counterclockwise promenade, their moving shadows thrown onto the ceiling and walls, creating an eerie backdrop.

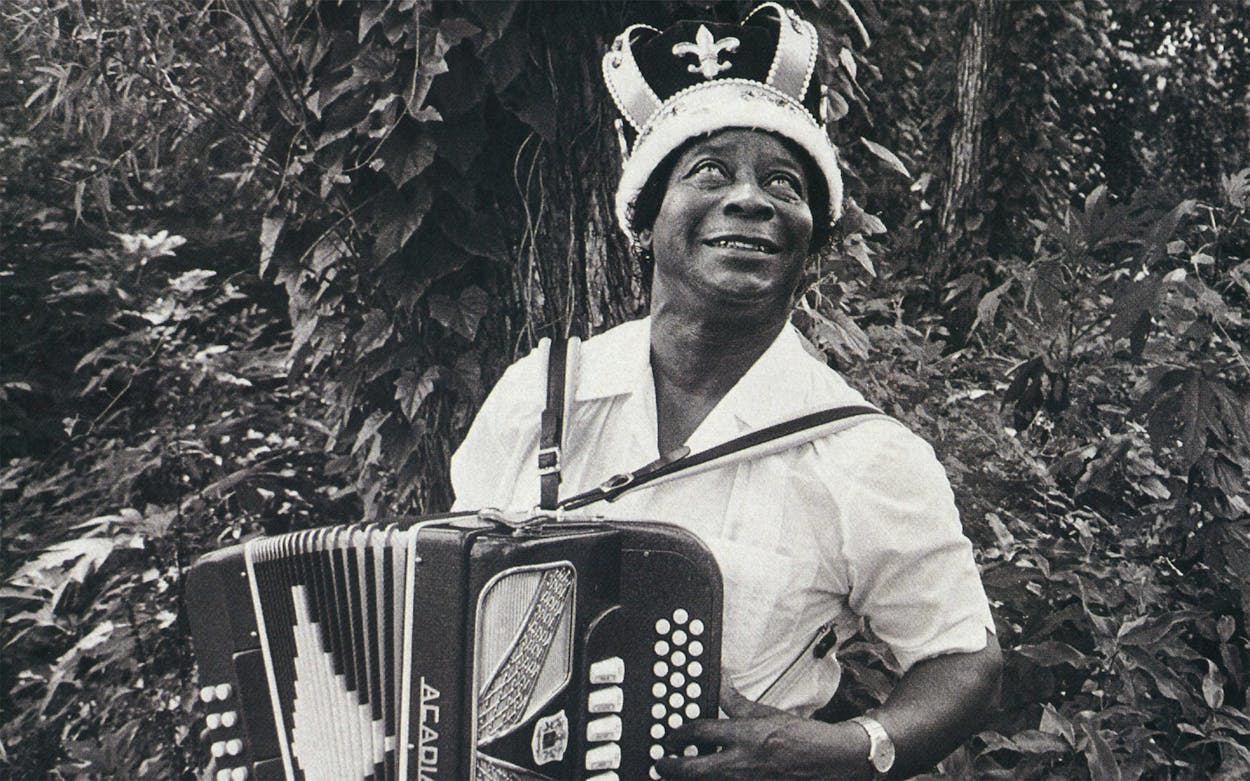

Until recently, the biggest draw at parish halls like St. Anne’s was Clifton Chenier and his Red Hot Louisiana Band. Though many bandleaders have worn crowns and sported royal monikers (e.g., Fernest Arceneaux, the New Prince of Accordion), all of them bowed in fealty to Chenier, zydeco’s best-known proponent and the first performer to export the sound beyond its traditional Louisiana and Texas borders. As an instrumentalist and entertainer, Chenier was without peer and so closely identified with the music that many speculated zydeco would die with him. Instead, his passing last December signaled open season. So many contenders and pretenders have been scrambling for a piece of Chenier’s title that zydeco has fragmented into fiefdoms like so many wrestling championships. Less than three weeks after Chenier’s funeral, Rockin’ Dopsie, the leader of the Cajun Twisters, the closest approximation to a rival that Chenier ever had, coaxed the mayor of Lafayette, Louisiana, to crown him the King of Zydeco. Dopsie’s callous disregard for a period of mourning and his perennial runner-up status stirred up controversy. Stanley Dural of Buckwheat Zydeco and the Ils Sont Partis Band called Dopsie’s stunt “crude,” which is sort of like the pot calling the kettle black, given Buckwheat’s proclivity for wearing bejeweled chapeaus since he switched from organ to accordion and broke from Chenier’s band in 1979. Chenier’s son C.J., himself a recent convert from saxophone to accordion, has inherited the crack Red Hot Louisiana Band, though at this point he is not yet a king, only another heir to the throne. John Delafose of Eunice, Louisiana, is another contender, at least according to the impassioned testimony of one man in St. Anne’s parking lot. Even Boozoo Chavis has entered the fracas, accepting the title of King of Calcasieu Parish from the mayor of Lake Charles, his hometown. Despite the honor, Boozoo has yet to trade his customary cowboy hat for something more regal.

In places like New York, Los Angeles, and London, the best-known zydeco artists are Buckwheat, Queen Ida, C. J. Chenier, and Terrance Simien. City folks may think they’re in the presence of the real thing when they listen to them, but what they’re hearing is watered down compared with what’s being played at the Houston dances. The city’s creole enclaves are substantial enough to support homegrown heroes like L. C. Donato, Wilfred Chevis (“King of Zydeco Radio”), Mitchell and his Zydeco Rockers, Little Willie and the Hitchhikers, and Pierre and the Zydeco Dots, plus clubs like the Continental Zydeco Lounge and Pe-Te’s Cajun Barbecue.

But the regional bands from Louisiana, specifically those fronted by Boozoo Chavis, Rockin’ Dopsie, and John Delafose, are the heart and soul of the scene. Family is their secret weapon. In their groups the old men lead and play accordion while the kids hold down the physically demanding rub-board and percussion positions, creating a delicate balance between tradition and fresh ideas. The fathers have the experience, wisdom, and box-office draw. The sons are constantly reinventing the sound, tailoring it to younger audiences. Top youth Geno Delafose, 16, invites comparison to Prince or Terence Trent D’Arby when he seductively strokes the rub board in his dad’s Eunice Playboys band. His charismatic rival is 26-year-old David Rubin, Dopsie Junior, whose suggestive wiggles and shakes outshine his father’s relatively sedate stage presence. That generational linkage is played out on the dance floor of St. Anne’s too, as teenage couples grind out a slow dance next to two Sunday-suited senior citizens maintaining a more respectable distance. Zydeco’s strength is its ability to defy the generation gap. When was the last time you danced to your parents’ music?

White Acadians gave zydeco its most obvious traits: French lyrics and the accordion. The similarities to traditional French folk music end there, both Cajuns and Creoles will tell you. Zydeco is considerably brassier, more obsessed with rhythm. It is also more prone to assimilate influences like rhythm and blues, soul, disco, and African and Caribbean music. Old guardians inject sentimental stuff into their repertoires—songs like Guitar Slim’s confessional “The Things That I Used to Do,” Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill,” Cookie and the Cupcakes’ “Mathilda,” and the lilting Memphis groove of Tyrone Davis’ “Turning Point,” the Staples Singers’ “I’ll Take You There,” and Johnny Taylor’s “Disco Lady” (reworked into “Zydeco Lady” by Boozoo Chavis). Relative pups like Buckwheat Zydeco and Terrance Simien and the Mallet Playboys are more likely to pull out “Hey Pocky Way” or something by the Nevilles. Nobody gets through the night without playing “Something on Your Mind” and “Don’t Let the Green Grass Fool You” at least once.

The small, diatonic Acadian accordions favored by Cajuns are frequently used, but most urban zydeco musicians prefer the complex Italian and German piano-key behemoths that give a fatter sound. The rub board began as an improvised washboard stroked with a spoon handle—the creole variation on the triangle once common in cajun bands—and evolved into a corrugated-metal vest that when scraped with a handful of bottle openers emits a grinding whir as sinister as a rattlesnake’s warning. Guitars, bass, drums, keyboards, horns, and even synthesizers can round out the accompaniment.

As one of the genre’s elder statesmen, Boozoo commands and receives a modicum of respect. If he lacks Chenier’s dashing stage presence, he compensates with a suitably cranky demeanor that borders on braggadocio. When I asked for an interview, Boozoo said it would cost the magazine 25 cents per issue, a fee I calculated would come to roughly $75,000. When someone requests Chenier’s “Ti Na Na” at St. Anne’s, Boozoo haughtily replies, “I only play my own songs.” He introduces one favorite by pumping his accordion’s bellows a couple of times before pausing and drawling, “We gonna give you some of that ‘Zydeco et Pas Salé.’ You think Clifton Chenier wrote that? I wrote that song. There’s where Clifton and Buckwheat got it from. Clifton and I came up together. And I tell you what—I’ve got a lot more where that come from. I’ve been doing this since 1955.”

Louis Simien hollers back that he remembers, all right. “He’d be great if he didn’t talk so much,” he says with a throaty guffaw.

A version of “Deacon Jones,” minus the bawdy rhymes, packs the floor. A sassy young lady in white pedal pushers cries out, “Play the bad version!” The dancers don’t return to their tables when Boozoo launches into an uncharacteristically driven interpretation of Bob Wills’s “Stay All Night.” The guitar licks may be country, but the swaggering, rocked-up beat is pure bayou. Inspired, Boozoo lifts his accordion above his head and punches out some fancy notes. In the middle of this extraordinary display of showmanship, a policeman walks to the stage and asks Boozoo to adjust the volume. Boozoo protests. “I’ve been all over the United States, and this is the first time I’ve been asked to turn it down,” he complains.

“Then play a waltz,” advises a skinny cowboy near the front. Boozoo scowls and steams.

“Go on, get on with it,” shouts a burly man in a work shirt and gimme cap, pooh-poohing the policeman. Boozoo tweaks a few knobs on the sound-mixing board and stomps into another two-step.

A little more than three hours into the set, Jane Champagne asks the band to take a break so she can raffle off the Jack Daniel’s and let representatives from other churches announce upcoming dances. Esteemed guests are acknowledged. By the time the band starts again, the beer has run out and Boozoo has handed over his mantle to Poncho, who, armed with an accordion, immediately loses all reserve. Though his attack is far more tentative than his old man’s, the kid shows promise. Poncho gets about thirty minutes before he gives back the plastic apron and squeeze box. Boozoo has time to sing “Oh Bye Bye” before the band unplugs and the doors swing open.

It is as pure a musical experience as I’ve found in Texas, so warm and friendly that the Saturday dance seems more like a reunion than a public function. Which it almost is, it turns out. On the way out the door, a dashing young man with jet-black hair and caramel-colored skin is introduced to a visitor as one of Boozoo’s cousins. He grins in acknowledgment of the accolade, then adds, “I found out I’m a cousin of Clifton’s too. Yeah, we’re first cousins.” At the lala church dance, everybody is family in one way or another.

How to find them: Upcoming dances in Houston-area churches are listed in “Around the Diocese” in the Texas Catholic Herald semiweekly ($10 a year, write 1700 San Jacinto, Houston 77002) and broadcast during the Telephone Road Show on KPFT-FM, 2 to 4 a.m. on Saturday mornings. Mail-order sources for zydeco records include: Maison de Soul, Drawer 10, Ville Platte, Louisiana, 70586 ($1, refundable with first order); Rounder Records, 1 Camp Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140; and Arhoolie Records, 10341 San Pablo Avenue, El Cerrito, California 94530. Arhoolie also carries the video anthology Clifton Chenier: The King of Zydeco on VHS for $40.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston