Some may boast of the prowess bold,

Of the school they think so grand,

But there’s a spirit can ne’er be told

It’s the spirit of Aggieland.

So begins the Texas A&M alma mater. Like school songs everywhere, it was not written to be controversial. But if you stop to think about the words, you might ask yourself, If the story is so great, so unique, then why hasn’t it been told? Why not tell it? You might wonder, too, whether Texas A&M has paid a price for not telling it, whether the lyrics hint at a circle-the-wagons attitude in the A&M community: that many Aggies, past and present, don’t care what the outside world thinks of Texas A&M, so long as the Aggie spirit remains a vibrant and living presence on the College Station campus. And you might consider whether a saying that Aggies have about that spirit—“From the outside, you can’t understand it; from the inside, you can’t explain it”—serves Texas A&M well or badly.

It so happens that Robert M. Gates, the president of Texas A&M University, has been thinking about these exact questions for the past four years. Don’t tell him that A&M can’t be explained. “I hate that phrase,” he says. “I don’t think it’s accurate. Texas A&M is a unique blending of academic excellence, tradition, and spirit. That is explainable.”

Gates, 63, knows a thing or two about large communities with distinct identities, long -established ways of doing things, and an aversion to explaining themselves, having spent his entire career before coming to A&M working for the Central Intelligence Agency, where he reached the top of the organization chart as director of central intelligence from 1991 to 1993. It may seem a strange course to go from the nation’s spymaster (although he came up through the intelligence-analyzing side of the CIA, as the agency’s foremost student of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, rather than through the covert-operations side) to the presidency of a large state university, but Gates finds more in common between the two places than you might think. “Both have very strong cultures,” he said. “Both cultures are very difficult to change. Both organizations think that no one on the outside understands us. And both believe that only we know how to do what we do.”

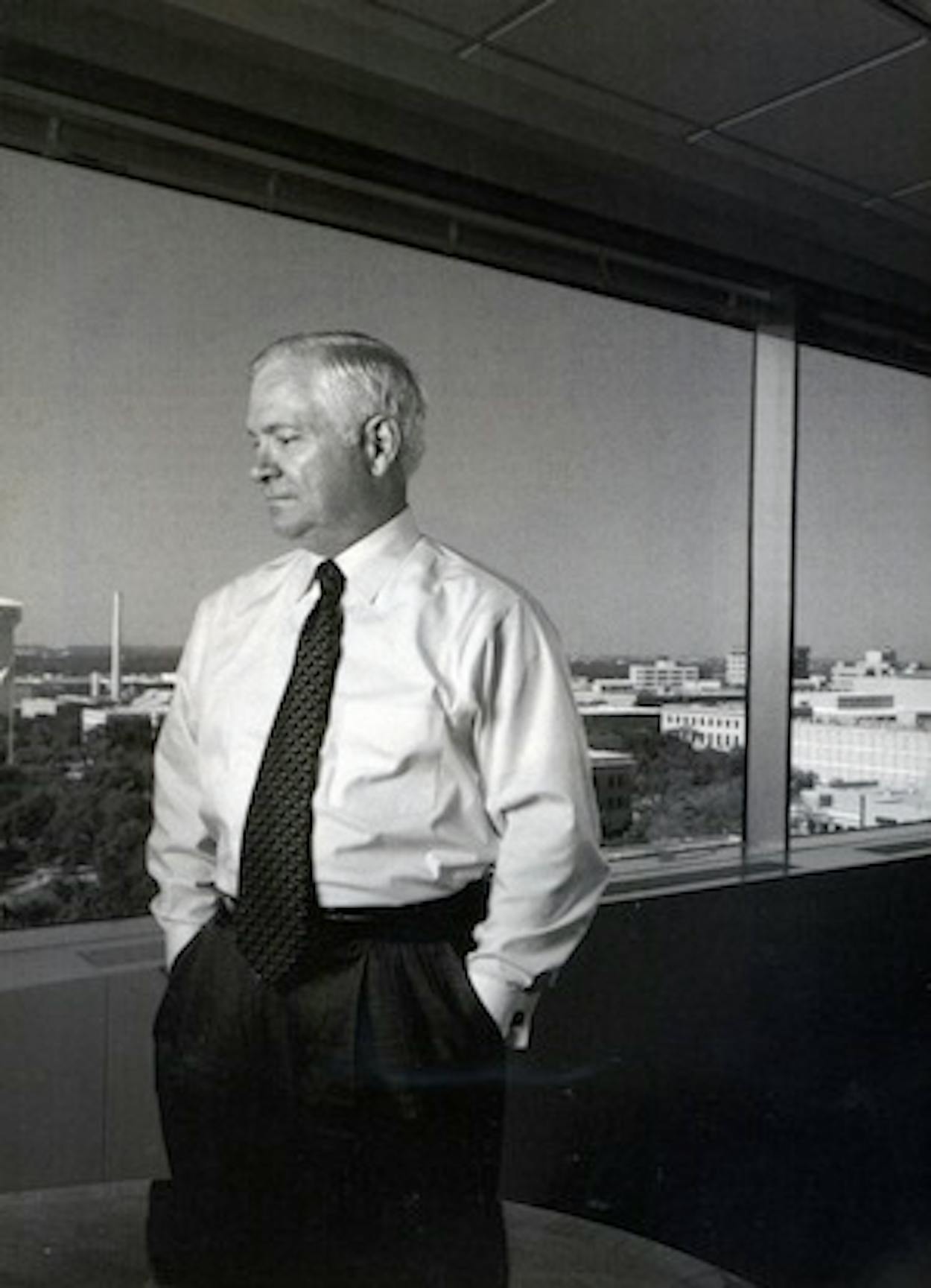

We were sitting at a table in his office, on the tenth floor of Rudder Tower, named for Earl Rudder, A&M’s greatest president, with a view looking north over the huge campus and beyond to the rich Brazos farmland that brought A&M to this spot 130 years ago. He has silver hair that lies obediently on either side of his part, a round face, and alert blue eyes—when I could see them. As we talked, Gates seldom made visual contact, preferring to fix his gaze on the distant panorama afforded by a picture window. His line of sight was a full ninety degrees to the right of where I was sitting. I have since mused about his body language, trying to guess at its meaning. Was it an old habit, a way of making sure that he wasn’t giving away any clues that could be “read” by a potential adversary? Was it a form of gamesmanship? Or was it his way of focusing, of shutting out extraneous stimuli to concentrate on his answers?

We had just returned from the photo shoot for the cover of this issue. From the steps of a columned administration building on the east side of the campus, we could barely make out in the distance the memorial to the victims of the 1999 Bonfire collapse. Surrounded by students wearing shorts and T-shirts (except for uniformed cadets), he had stood erect and motionless for almost half an hour in a black suit, under a merciless sun. Offered a bottle of water, he refused. Advised to shuck his coat, he declined. When the shoot was over, not a bead of sweat showed on forehead nor brow, not a strand of hair had strayed from its assigned place. Now, coat shucked at last, he wore his patriotism on his sleeve, literally: gold cuff links with a design of the American flag.

A man who will not compromise with the sun is a person to be reckoned with, and that is how Bob Gates has come to be viewed at Texas A&M. As the university’s twenty-second president, he is determined to leave his mark on the school as few previous leaders have done. One can infer from his CIA background that he is not easily dissuaded from his chosen course or prone to doubting his own powers of observation. And his chosen course is to change the way the world views Texas A&M, not to mention the way Texas A&M views itself.

To accomplish this, Gates has created a new position, chief marketing officer and vice president for communications, whose job will be to oversee what Gates calls the “rebranding of Texas A&M.” Now, I daresay that most Texans, to say nothing of most Aggies, regard A&M as already being one of the best-branded schools in America. There is Harvard, there is Berkeley, there is Notre Dame, and there is Texas A&M. Some longtime Aggies have expressed skepticism to me about the need for rebranding; one described it as “a solution looking for a problem.” But Gates is determined to see it through. “There is a huge opportunity cost if we don’t do it,” he said. “We need to significantly improve the public’s knowledge and perception of the university.”

The branding campaign is only one of the ways in which Gates is trying to transform A&M. It is hard to come up with an area of the university that has escaped his gaze—or his action. The administration. The faculty. The athletics department. The Corps of Cadets. Minority admissions. Graduate programs. A new undergraduate degree program. How buildings ought to be utilized. How decisions get made. Even the food service. I can’t imagine a president of the University of Texas spending ten seconds of his term thinking about the food service. Gates canned the top five managers at A&M and hired replacements from Stanford. Why? He wants A&M’s students to be broadened by exposure to different cultures, and he thinks that new kinds of food are one way to do it. Perhaps it is not so surprising, these days, that A&M now serves sushi, but who would have thought the day would come when campus dining halls offered Soul Food Fridays? And coming soon are Organic Farmer’s Market Thursdays.

All of this transformation is occurring at a university that, deep down, has never wanted to be transformed and has always viewed change with a narrow range of emotions bracketed by suspicion and hostility. This article is my sixth story about Texas A&M in nine and a half years, and while the nominal subjects have been different, all stories about A&M have the same underlying theme: the need for the university to evolve, as seen by its leaders, and the continuing antipathy to change, as voiced by its present and former students. That the resistance is based upon affection—the unimaginable degree to which Aggies mate with their school for life and ask nothing more of it than that it remain the same as when they were students—does not make it less difficult to overcome. If anything, the opposite is true. Every Aggie is a self-appointed guardian of the Aggie spirit, eternally on the alert for signs of slippage.

The student newspaper, the Battalion, and particularly its Mail Call column, is a forum for such concerns. “I call on all Aggies out there to start living up to our Code of Honor and to those of us who do to join with me in no longer tolerating those who are being bad Aggies,” wrote one senior girl, who was upset that a male student had allowed several friends without the proper tickets to sit with him at the first home football game, thereby crowding other fellow Aggies, including herself. Similar feelings were voiced in a letter from a junior girl: “Call me old fashioned, but I believe in chivalry.… I am very disappointed by the actions of many of the gentlemen on the Texas A&M campus. I have been riding the bus … and every time I get on, there are plenty of gentlemen who are seated, and not one of them has offered me (or any girl for that matter) their seat.” Another senior girl expressed alarm that the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (COALS) was going to change its name to the College of AgriLife Sciences, as part of its own rebranding effort. “As a member of the college, I am proud of my agriculture background, and I do not support the name change. For some time now, the COALS slogan has been, ‘Putting the ‘A’ in A&M since 1876.’ Why does the administration now, after 130 years, want to take that ‘A’ out?” It’s not being taken out, of course, just getting a makeover.

The historical dilemma of Texas A&M is that this love for the school, this respect for tradition and values, is both A&M’s greatest strength—the reason why its current capital campaign has surpassed its $1 billion goal by some $300 million with several months to go—and, at times, its greatest weakness. Because tradition so often has stood in the way of change, it has occluded the perception of Texas A&M even in its home state. Few realize what an academic powerhouse A&M has become and what a lofty goal its leaders have set, dating back to Gates’s predecessor, Ray Bowen: to become one of the top ten public universities in America by 2020.

This is why Bob Gates wants to rebrand Texas A&M. One does not spend a career in Washington, working for an agency that does its work in secret and cannot publicly defend itself against its critics in the executive branch, the Congress, and the media, without learning that perception can become reality. He has never hidden his intentions. “I am an agent of change,” he told the A&M Board of Regents when he was interviewed for the job of president (for which his competition was none other than former U.S. senator Phil Gramm). “If you don’t want change, you don’t want me.”

TWENTY YEARS AGO, ROY SPENCE SAW THE future. “Purpose-based branding,” he told me. “It means that what a company stands for will be as important as what it sells. Visionary companies have a core purpose beyond making money.” A co-founder of the Austin-based advertising agency GSD&M, Spence has fashioned this pitch into a mantra. He loves to quote from Built to Last and Good to Great, Jim Collins’s best-selling books about corporate management, which set out to discover what separates the most successful companies from the rest of the pack. Steve Moore, A&M’s new chief marketing officer, says of Spence, “He is a true believer, an evangelist.”

Spence grew up in Brownwood, played quarterback under the legendary coach Gordon Wood, and has a rugged West Texas face under his blond hair to show for his years outdoors in the wind. When he gets excited, his voice gets softer, not louder, and smooth as purée. “You can’t make up your values,” he said of branding. “They have to be real. We discover and bring to life the values of companies.” He told a story about how Southwest Airlines chairman Herb Kelleher, before the company’s twenty-fifth anniversary, asked him, “What does our brand really stand for?” and after some discussion about making it possible for people who had never flown before to be able to afford to fly, Kelleher came up with “to democratize the skies.” That’s all Spence needed to know. “We took Herb out of the airline business,” he said, “and put him in the freedom business. Southwest even has a freedom manifesto. A flight attendant is free to sing. It helps us recruit.”

Two years ago Spence gave a talk to the American Council on Education, which bills itself as the unifying voice for higher education, in which he volunteered to rebrand higher education. “We’ve got to get the public to support higher ed again,” he told me. “It’s our last hope to be a solutions machine for the world.” Gates was on the ACE committee that decided to bring Spence onboard, and Moore ultimately retained GSD&M to do purpose-based branding for Texas A&M. That Spence was a teasip—he graduated from UT in 1971—who had previously done a branding campaign for UT was no obstacle. The cultures of the two schools are so different that their rivalry, always fierce in athletics, does not extend to education. “He liked the process we use,” Spence said of Gates. “Interviews with alumni, faculty, students, administrators, parents, high school guidance counselors, companies that hire A&M graduates—these allowed us to discover the university’s purpose. Purpose is the North Star.”

As I listened to Spence, I found myself thinking, “Doesn’t A&M know what its purpose is? I know what it is. It’s to make Aggies.” And I mean that in the best sense. The university goes to extraordinary lengths to get students to “buy in.” The process starts with Fish Camp, three-day summer orientation sessions in East Texas at which freshmen learn yells and Aggie traditions and, more seriously, begin the process of feeling part of the extended Aggie family. (At a campus-area eatery, I saw a girl wearing a blue Fish Camp T-shirt that read “Where Else But Aggieland Can You Whip It Out and Hump It?”) By the third day, love for the school has been instilled. One reason for the success of Fish Camp is that it is entirely planned and run by students. In fact, many things at A&M are student run. Students drive the buses that shuttle other students around campus. Students run the career fair at the business school. Once school starts, freshmen are encouraged, both by the university and by other students, to join student organizations, which number around eight hundred. The idea is not just for everyone to find a niche but also to give students a chance to develop into leaders. (A&M even offers a major in Agricultural Leadership and Development.) All of this extracurricular activity is known at A&M as “the other education,” and it is valued as highly by the university as the real education.

The branding process for A&M identified six core values: integrity, loyalty, excellence, leadership, selfless service, and respect. The last core value addresses a longtime problem at A&M—as Moore puts it, “respect, acceptance, and inclusion for all Aggies with respect to race, color, gender, and religion.” All of these values point to a core purpose: “to develop leaders of character dedicated to serving the greater good.”

If you’re wondering where this is leading, well, so did I. If A&M wants the world to know how good it is academically, why are most of its core values nonacademic? Why does branding appear to have more to do with the other education than with traditional education?

The answer, Spence explained, lies in yet another sacred text about corporate management: Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation, by William Strauss and Neil Howe. Generation X is approaching middle age and will soon be replaced by the Millennials—a generation born after 1981, who came of age starting in the year 2000, and who, the theory goes, has a different set of values from the cynical, selfish Xers. Millennials, according to Strauss and Howe, are confident, optimistic, goal oriented, civic minded, inclusive, and patriotic.

Finally, I got it. Football coach Dennis Franchione would understand: Rebranding is about recruiting. It’s about eradicating an image of the university that is out-of-date but still persists—that, seen from a distance, A&M, with its arcane rituals and its intense sense of family, sometimes resembles a cult more than a culture. Now its core values and its purpose statement are aligned with the values and ambitions of the Millennials. How does a university teach leadership and service? The best way is to find young people who already have those traits. As Steve Moore told me, “We want to get kids who know what they’re getting.” Sometime this fall, A&M will send out its rebranding campaign to high school guidance counselors. And soon afterward, the Millennials will come to realize that they are Aggies—new, improved, thoroughly modern Aggies—waiting to be made.

BOB GATES CAME TO TEXAS A&M in 1999 as the interim dean of the George Bush School of Government and Public Service. The A&M regents had previously separated the school from the College of Liberal Arts, and Gates had taken the job at the request of Lieutenant General Brent Scowcroft, the president of the foundation that oversees and supports the Bush presidential library on campus. “It’s largely honorific,” Scowcroft told Gates, who had been Scowcroft’s deputy at the National Security Council in the George H. W. Bush administration. “It will require a day or two a month for nine months.” Gates smothered a sardonic laugh at that memory. “That was classic bait and switch,” he said. “It turned out to be two weeks a month for two years.” Gates and his wife resided, as they do now, at one home ninety miles north of Seattle and another on remote Orcas Island—“From the tallest mountain on Orcas, you can see Vancouver”—and at first he was not enthusiastic about spending a lot of time in College Station.

During his first year as dean, he stayed in the regents’ quarters, in the Memorial Student Center, smack in the middle of campus. “I saw a lot,” he said. The old CIA instinct to observe, to analyze, to conclude was insuppressible. Gates attended meetings of the deans and saw that the crucial decisions—about funding, for instance—were made at a higher level, by vice presidents who were nonacademics. “The deans were an asset that was not being taken advantage of,” he said. When Ray Bowen announced his retirement, the battle to replace him came down to Gates and Phil Gramm. The story at the time was that Rick Perry, who had become governor in 2000, wanted the regents to choose Gramm, but Bush 41 was influential in the eventual choice of Gates.

The moment when Gates signaled his intentions was the graduation ceremony in December 2002. The traditional seating arrangement was for attending faculty members to be seated almost out of sight, on the arena floor, with the vice presidents onstage, in the front row, and the deans seated behind them. One of Gates’ stated goals for A&M was to “elevate the faculty,” but no one knew he meant it physically as well as conceptually. Early arrivals at the ceremony were startled to see that new construction had expanded the stage, allowing the faculty to sit on the same level as the rest of the A&M leadership. The front row was now occupied by the deans, with the vice presidents seated behind them. Coming from a former Sovietologist, who had made a career of noticing who was standing next to whom at Kremlin events, the message was unmistakable: The new arrangements represented a revolutionary transfer of power, from administrators to the faculty and deans. When I went to A&M in 2004 to write about the university’s growing pains as it wrestled with change, many of the people I interviewed brought up the ceremony as the signature moment of Gates’s presidency.

At the time, Gates and A&M faced two major problems (and a host of smaller ones) that threatened to reverse the gains A&M had made during the Bowen years. One was a backslide in academic performance since 1997, when the university cracked U.S. News and World Report’s list of the nation’s top fifty schools for the first time—and archrival t.u. didn’t. By 2004 A&M had sunk to a six-way tie for sixty-seventh. One of the reasons was that A&M had the worst ranking among major universities in the percentage of small classes (fewer than 20 students) and the percentage of big classes (more than 50). The student-faculty ratio was an abysmal 22 to 1. All of these numbers could be attributed to the failure to keep up with faculty hiring. Gates had announced his intention to create more than four hundred positions to be filled by the start of the 2007–2008 school year, a goal that seemed impossible to meet and yet one on which the realization of the university’s academic ambitions depended.

The second issue was diversity. For a major public university, whose stated goal is service to the people of Texas, A&M’s number of minority students is an embarrassment. After the Hopwood case brought an end to affirmative action at all Texas colleges a decade ago, A&M’s freshman class of 1996 included only 230 black students and 713 Hispanics. When the U.S. Supreme Court decided in 2003 that affirmative action admissions programs were constitutional after all, Gates had to decide whether to use race- or ethnicity-based admissions. His decision was no. There was an uproar from some faculty members—a Hispanic professor wrote Gates that he was perpetuating the image of Aggieland as “Crackerland”—but Gates didn’t budge. He invoked A&M’s history as a land-grant college, whose mission was “to make higher education available to all classes of students, not just a select few.” It would seem that this argument would apply equally well to embracing affirmative action as it does to rejecting it, but Gates did not spend thirty years in Washington without developing good political antennae. Doubt about the benefits of diversity still runs deep at A&M. In a recent letter to the Battalion a senior wrote, “It never ceases to amaze me that a man as smart and articulate as President Gates could be duped into buying into the diversity mantra: ‘we will not tolerate intolerance’. … As long as student leaders and administrators continue to worship the idol that is diversity, our students will never recognize that we are all Aggies. Only love for Aggies—not some desire for an idealistic utopia filled with a politically correct blend of races—will bring safety to our students, and an end to hateful stupidity.”

Gates didn’t need race-based admissions to get the numbers moving in the right direction; he just needed a new admissions strategy. After he rejected affirmative action, he eliminated legacy as a factor in admissions for the children of former students. (This year he enlarged the freshman class by 850, which improves the odds for everyone, legacies included.) One admiring faculty member who heard Gates defend his decision told me, “It sent chills down my spine. He asked us to put ourselves in the mind-set of a family who had never had the opportunity to send their kid to college. Ask yourself, ‘Is admitting legacies fair to that student? ’ If we’re going to truly change the stereotype, we have to change our mind-set.” And what is the stereotype? It’s what you see on TV during Aggie football games. All male. All white. All military. All the time.

Gates has put considerable effort and resources into increasing minority enrollment. A new admissions policy junks the old quantitative method of assigning points for grades and test scores. Around 65 percent of the freshman class is made up of “automatic admits”—students who finish in the top 10 percent of their class or score higher than 1300 on the SAT. All of the remaining applicants receive what A&M calls a “holistic full-file review.” The objective is to identify “students who have the propensity and capacity to assume roles of leadership, responsibility, and service to society.” Students are evaluated in three ways: academic achievement (grades and test scores), personal achievement (honors, extracurricular activities, community service), and distinguishing characteristics (educational level of parents, family responsibility and obligations, fluency in a second language, and overcoming adversity in the educational environment). Reviewers never see any information about ethnicity, although “distinguishing characteristics” is clearly a category that generally benefits minority applicants along with first-generation college students. The new admissions policy has continued to attract students who are the first in their family to attend college. For several years, including this year, these students have made up at least a quarter of the freshman class—an astonishing number.

A&M has established scholarship programs for first-generation students (ethnicity is not a criterion); it has opened recruiting centers in Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, Bryan, and several sites in South Texas. Gates himself makes recruiting visits to inner-city schools. But the yield is still small: just 256 blacks and 1,001 Hispanics among the 7,104 freshmen who entered A&M in 2005. In percentage terms, the increase looks better: Hispanic freshman enrollment was up 45 percent in two years, black enrollment 62 percent.

Why hasn’t A&M had more success attracting blacks or Hispanics? One of the obstacles to attracting more minorities, everyone concedes, is that too many Aggies haven’t gotten the memo that “respect” is a core value. In his State of the University address last year, Gates said, “[Our] welcoming and friendly environment makes a gigantic university into a family, the Aggie family, where we respect each other, look out for each other, bond together for the rest of our lives.” Of those “who would exclude and insult some members of the Aggie family,” he went on to say, “their behavior belies all we believe not just about the Aggie family, but the importance of character, integrity, and ethics here at Texas A&M.”

You will find racial prejudice on any campus, but at A&M it has the added complexity of being part of the fear of change that goes all the way back to the admission of women in the sixties—fear that if the kinds of students who come here are different, A&M will be different too. This attitude applies not only to minorities and foreign students (one of whom was assaulted in September) but also to liberal arts students. When the report establishing A&M’s long-term goals, known as Vision 2020, came out during the Bowen presidency, one of its goals was to build up the liberal arts, and Berkeley was included among the peer institutions to which A&M was compared. Big mistake. Many former students objected, saying that the last thing they wanted was for A&M to be like Berkeley. (Not to worry.) And yet the reality of Texas A&M is often very different from its image: The College of Liberal Arts graduates more majors than agriculture, business, or engineering, the colleges that carry out the university’s original mission.

The resistance to change is in the DNA at Texas A&M. The reason Earl Rudder (1959-1970) was A&M’s greatest president is that he was able to overcome this resistance and bring about the changes that rescued the university from a slide into irrelevancy: the admission of women and the end of compulsory membership in the Corps of Cadets. His decisions reversed the trend of declining enrollment in the anti-war sixties. No other president could have done what he did. Rudder was not only an A&M graduate but also a war hero. On D-day he commanded a Ranger battalion that scaled one-hundred-foot cliffs at Omaha Beach under heavy fire to destroy German gun emplacements and help the invading forces establish a beachhead. His unit suffered a casualty rate of more than 50 percent.

If you think this didn’t matter at Texas A&M, and if you think that Bob Gates’ service to his country doesn’t matter, you don’t understand this place at all. Aggies take patriotism very seriously. The university’s seven Congressional Medal of Honor winners are remembered in the Memorial Student Center. Even so, many Aggies of that era believed that Rudder had destroyed the university, that the Aggie spirit would never survive the changes, but he was untouchable. Undoubtedly, there are Aggies today who feel the same way about some of Gates’s changes, from committing to raise minority enrollment to something as insignificant (on any other campus) as converting Hotard Hall, an ancient dormitory that was regarded by its residents as a hotbed of the Aggie spirit, into an office building. For an occasional visitor like me, however, the wonder is not how much A&M has changed but that, in all the ways that matter to Aggies, it has remained the same. Name one other school where a women’s soccer game would draw an estimated 8,500 people, as the Aggies did, against North Carolina, an NCAA record.

TO RETURN TO TEXAS A&M two years after the turmoil of 2004 is to encounter a different university. The faculty members I talked to then had serious doubts whether many of the new positions could be filled. A&M is a good place for married faculty, I was told. But Bryan-College Station was not a good place for singles. You couldn’t go out in the evening without running into students. Nor was it a good place for minority faculty. The local black and Hispanic communities were poor. Minority faculty members had to go to Houston to buy cosmetics and hair products. Some chose to commute from Houston, Austin, or some of the small towns in between. What I, and perhaps the faculty itself, didn’t realize is that there are many more good professors looking for jobs than there are good jobs. Two years later, A&M has filled 333 of the 447 positions and the student-faculty ratio is down 20 to 1. It is on track to meet Gates’s deadline of fall 2007.

Faculty members love to grouse. There were plenty of grousers two years ago. This time, I found none. Take sociology professor Rogelio Saenz. A staunch supporter of affirmative action, he was highly critical of Gates’s decision to reject it. And now? “I’m pleasantly surprised,” he told me this fall. “This has been the most exciting time in twenty years.” He continues to criticize the decision not to use race as a factor in admissions—“We’ve got a long way to go”—but he also found much to praise in new scholarships that have been created for low-income students. Other presidents talked a good game, he said. The difference is, “Gates has marshaled resources.”

The arrival of new faculty has done far more than just reduce the student-faculty ratio. It has reinvigorated the university. “There’s more energy here,” Saenz said, and this was not the only time I heard this view expressed. One of the concerns I had about adding a large number of faculty members in a short time was where they would come from: major schools or, in an effort to get the numbers up quickly, the backwaters of academia. Sociology was given six new positions, Saenz said. One, an endowed chair, went to Joe Feagin, a past president of the American Sociology Association, who had taught at UT and more recently at the University of Florida. Another established professor came from the University of Georgia. His Ph.D. was from the University of Chicago. The other four were entry-level assistant professors, three of whom had just received their Ph.D.’s and the fourth had earned a postdoctoral fellowship. They came from the University of Pennsylvania, UCLA, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. No backwaters here. This is a stunning accomplishment. Repeat this across 65 departments, and the academic future of A&M is ensured for the next decade. Gates has also taken steps to ensure that what A&M has built up will not be easily taken away. He has raised the salaries of professors who fell behind their peers during a period of tight budgets, upping the cost to colleges that might want to steal them .

Equally surprising to me was the change that has taken place in the Corps of Cadets. Its numbers had been dwindling for years, to the point where the unthinkable was being thought: that the day might come when the Corps might cease to exist. One of the biggest obstacles to increasing the Corps’ numbers was the perception that a freshman couldn’t be in the Corps and survive academically. The reason was a tradition known as “Corps games,” in which upperclassmen made freshmen who had somehow messed up do physical training instead of attend class. The harassment could last all day. The commandant of the Corps, Lieutenant General (ret.) John Van Alstyne, was determined to put a stop to it but encountered a we-had-to-do-it-now-they-have-to-do-it-too attitude from the upperclassmen. Writing about this in 2004, I said, “The Corps is a dying institution.” Reports of its death turned out to be greatly exaggerated. This year, the Corps’ ranks are up from 1,700 to more than 1,800, the number of female cadets (207) is at an all-time high, and the grade point average of freshmen in the Corps last spring was higher than the university’s overall average.

Many of the changes Gates has made have come in the area of governance. And most of these are too prosaic to talk about. It is a task force here, a committee there, a new initiative over there, but they all add up to a better way of running the university—more businesslike, more receptive to new ideas. He seldom rules by fiat. His style is to create a climate in which change is encouraged and bring in a person who is amenable to it. He did not originate the change in the name of the College of Agriculture, but he replaced a longtime dean with a new one. That she happened to be the first woman dean in the history of the college was another signal to the old boys in ag that change was coming. (I wonder if the display that greets visitors to the college—“The Pork Hall of Fame”—is long for this world.) And the old boys got the signal. “We have fourteen departments, and money was always distributed according to historical allocations,” one ag professor told me. “Now we have department reviews. I’ve been here thirty-one years, and we’ve never moved money around. We always worked on the principle that the only person who really likes change is a baby with a dirty diaper. This is the new world.”

The symbolism embodied by the name change matters to Gates. As the rearrangement of the people on the stage at graduation indicated, it is part of his governing style. One of his priorities was to make room for the newly hired professors to have office space in the central part of the campus, where they could interact with students. This required moving mid-level administrators to the periphery of the campus. Now these “bean counters,” as I heard them referred to, have been relocated to a new complex across a major thoroughfare from the main campus, behind the vet school.

Faculty and staff at other universities may regard these changes as the norm rather than the exception. But A&M is located in a relatively small community, far from the kind of scrutiny that occurs at UT and other big universities, and it evolved differently from other colleges. “This is an old university, but it’s one of the youngest comprehensive research universities in the country,” Charles Johnson, the dean of liberal arts, told me. A&M didn’t have faculty tenure until the late sixties. It didn’t have a faculty senate until the eighties. Administrators who were not academics made many of the decisions about where money would be allocated. The administration itself was inbred; most of the people who ran A&M were themselves Aggies. Too often, these administrators bought into the old Aggie idea that the heart was more important than the head. “We don’t want to say we’re only spirit and values,” says Steve Moore.

Another newfangled Gates notion—not entirely welcome to old hands—was that, in an era when the state’s contributions to higher education were not as generous as they once were, the university should be run more like a business. He brought in a new chief financial officer, and among the operations that face revamping or elimination are the faculty club, the purchasing department, and the nonperforming dining halls; any peripheral service that is losing money is history. The old-boy network may not be gone entirely, but it is endangered: About four hundred staff positions have been eliminated since Gates became president. “I was not brought here,” he told me, “to be everybody’s friend.”

No area of the university is more enthusiastic about Gates than the faculty. This attitude had already taken hold two years ago, when Marty Loudder, then the speaker of the faculty senate, told me, “I’d walk through hot coals for that man.” The current speaker, Doug Slack, said Gates told him, “I will not make a decision of importance to the faculty without consulting the faculty.” When a proposed intellectual property rule required faculty members to get permission from the Texas A&M System to write a book, the faculty was able to get the policy changed. One morning, when Gates was on vacation, Slack got a call from him. Gates had just read a book, Excellence Without a Soul, about how Harvard’s faculty had failed the university and its students; he was bringing back copies for Slack, the provost, and the vice presidents to read and discuss at a retreat. “Think about what we want Texas A&M graduates to be. How do we get them there?” Gates said. It had been thirty years, Slack told me, since anyone had given him homework.

As far-reaching as these governance changes were, what really matters at a university is academics. Here, too, Gates has made some important moves. A&M has always emphasized undergraduate education; many of its Ph.D. programs are of recent vintage. It has had trouble competing for good graduate students because major universities typically pay for their tuition and also provide a stipend. This has not been the case at A&M—until now. You may ask, “So what?” The answer is that in the academic world, a university’s reputation depends more on the quality of its graduate students than its undergraduate students. Where those students get hired as professors— Berkeley or Boise State—affects that reputation. It’s strictly word of mouth. A&M didn’t provide the money to compete for top graduate students. Now it does: Last year the university provided $8.4 million in tuition for graduate assistants.

Of all the changes Gates has made, he believes that the elevation and expansion of the faculty is the most important. He knows—I’m speculating here, not paraphrasing him—that one of the greatest threats to A&M’s academic renaissance is a return to the bad old days (bad old decades is more like it) when the old-boy network ran the university. There will always be tension at A&M between Old Aggies and New Aggies. The difference is not age but outlook. Only a system of governance that guarantees the faculty a voice in decision making can keep A&M on the track Gates has set for it.

“Leadership in large public institutions requires a skill set different from the private sector,” Gates told me. “A&M and the CIA have this in common. Professionals in the organization got there before you were there and will be there after you leave. For changes to last, the professionals have to assimilate the changes and make them their own. My time here is finite. I want to build something that will long outlast me.”

AS YOU MIGHT EXPECT, Bob Gates is not a man who reveals himself. I have been around him three times, once in 2004 and twice for this story. He is one of the most consistent personalities I’ve ever met. He’s all business, a man under total self-control. He doesn’t fidget. He isn’t a backslapper. He doesn’t make small talk. He doesn’t boast; neither does he engage in false modesty. He is a motivator, not a cheerleader. He is always polite. He wears an air of authority as if it were tailored by Brooks Brothers. He answers questions fully but volunteers little. Most of his laughter comes from a finely developed sense of irony. I would back him to the hilt in a no-limit poker game.

And that would be all that I could tell you about Gates, except that he wrote a book—quite a good book, in fact. From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider’s Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War is as compelling a history of the U.S.-Soviet rivalry as you’re likely to read. You might get confused by CIA initials—DCI, DO, NIE—and you may learn more about Angola than you care to know, but Gates the personality comes through in these pages and so does the CIA. That sense of irony appears in the form of a photograph of a poster with a head shot of Gates talking into a microphone. “WANTED” it reads. “Robert Gates. Director of CIA. For violation of international law and human rights violations. CIA OFF CAMPUS.” Underneath, Gates’s caption says “Public esteem: one of the rewards of being head of CIA.”

Gates joined the CIA in 1966, during the Vietnam War, fresh out of Indiana University. By 1968 he was an analyst of Soviet policy in the Middle East and Africa. He opposed the war, as did most of his CIA friends, and even marched in protest of U.S. activity in Cambodia. “Popular impressions then and now about the CIA—especially as a conservative, Cold War bureaucratic monolith—have always been wrong. … ” He writes of the influence of the counterculture, of experiments with marijuana by supervisors, of anti-Nixon posters and bumper stickers that “festooned CIA office walls.” Nixon comes in for some harsh words. Richard Helms, then the CIA director, told a story about going into the Oval Office just as Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird was leaving. Nixon pointed at Laird and said, “There goes the most devious man in the United States,” to which Gates adds, “Some accolade, considering the source.”

Gates’s motivation for writing the book, he told me, was to let the public know how well the agency performed its duties—especially its evaluations of Soviet military and economic strength—during the Cold War, despite continuing attacks from the left and the right. The majority of the book focuses on the Reagan and Bush administrations and the climax of the Cold War. For most of this time, Gates was either deputy director of central intelligence or, under Bush, director. He was always a skeptic about Gorbachev, always believed he was a Communist at heart rather than a true reformer. He also believed from the beginning that the Soviet Union could not sustain its vast military buildup and its foreign adventuring without risking economic collapse. In all of this, he was proved right. Gates occasionally allows himself an I-told-you-so, but he also owns up to his misjudgments.

What I found fascinating, though, was the early part of his career, when we see him learning the lessons for leadership he would later put to use, first at the CIA, then at Texas A&M. He wrote the book in 1996, when A&M wasn’t even on his radar screen, but the lessons survive to the present day. Of arms limitations negotiations with the Soviet Union, he writes about senior American officials who “not only lost sight of the forest but mistook tiny shrubs for trees.” Gates knows the difference between shrubs and trees. He has little use for James Schlesinger, a CIA director whose treatment of people was “crude, demanding, arrogant, and dismissive of experience.” But he praises another director, William Colby, who “was friendly and treated us with courtesy” and likewise Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, who “treated support staff—secretaries, security people, the Situation Room staff, baggage handlers—with respect and dignity.” This reminded me of a story by A&M business professor Ben Welch, who told me of encountering Gates on campus. “I’m Ben,” the professor said, to which Gates responded, “I know you. Business. We’re lucky to have you.”

In 1974 Gates joined the National Security Council staff under Henry Kissinger. “A common thread of our days,” Gates writes, “was the fruitless effort to persuade the bureaucracy, and especially the State Department, that they worked for the President and might occasionally make time in their busy schedules to support his requirements and implement his policies.” Now, at A&M, Gates wants everybody to be on the same page when it comes to crucial matters like welcoming minority students.

Most of all, Gates saw events with a startling clarity. He developed the ability to see what others could not. Most Americans believed that Jimmy Carter was a weak president toward the Soviet Union whose emphasis on human rights was, as Gates describes the prevailing viewpoint, “naïve and counterproductive.” Not Gates. By emphasizing human rights violations, Carter “became the first president since Truman to directly challenge the legitimacy of the Soviet government in the eyes of its own people. … His approach marked a decisive and historic turning point in the U.S.-Soviet relationship.” This capacity for insight against the conventional wisdom explains why he has so many initiatives going at A&M all at once; trained during the urgency of the Cold War, he can’t see a problem without wanting to fix it. But he was not blind to Carter’s shortcomings, his infamous propensity to micromanage (“We sometimes referred to him as the nation’s ‘chief grammarian,’ ” he writes. “He even corrected CIA’s President’s Daily Brief, and once wrote Brzezinski a special note to remind him that Mrs. Carter’s name—Rosalynn—was spelled with two n’s”), and his inability to resolve disagreements between advisers. Even his critics at A&M would not accuse Bob Gates of not knowing how to make a decision.

In the late seventies, Gates served as executive assistant to Stansfield Turner, Jimmy Carter’s choice to head the CIA. Turner was widely disliked in the agency, and Gates has little good to say about him. He describes Turner as an “agent of change,” but one who went about achieving it in the wrong way. Gates writes, “His failure to build a substantial internal constituency for his changes led to the reversal of his initiatives very quickly after his departure.” Nothing has engaged Gates more at Texas A&M than building internal constituencies and trying to perpetuate his reforms. Reflecting on Carter’s unrecognized contribution to America’s victory in the Cold War, Gates quoted an observation by the late columnist Walter Lippmann that applies equally to Gates’s efforts to change A&M: We must all “plant trees we will never get to sit under.”

IN EARLY SEPTEMBER GATES went to Baghdad with, among others, James Baker, to evaluate the situation in Iraq for President George W. Bush. That was the second time the White House had turned to Gates. In January 2005 Andy Card, then chief of staff for Bush, called Gates to ask if he would take the newly created post of director of national intelligence, or, as it was called, “Intelligence Czar.” Gates did not want to leave A&M, nor did he want to return to Washington. And he was well aware of the pitfalls of the job. “The DNI only has budget authority,” he told me as we drove back to Rudder Tower in the golf cart Gates uses to get around campus. “He decides how much money each agency gets. What good does that do? If you’re director of NSA [the National Security Agency] and the Secretary of Defense can fire you, who are you going to listen to? That was one reason not to take it. I couldn’t have hired or fired the head of a single agency.”

But there was more to it than that. Gates agonized over the decision for seventeen days. He eventually decided, as he said in his State of the University speech in 2005, “that if I might be able to help make America safer in a dangerous time, then I must, and therefore had to accept the position—and leave A&M.” He wrote an e-mail to all Aggies, which would be sent out as the introductory press conference in Washington began. It ended, “I … wanted you to know that this appointment was due to no initiative of mine, that the decision was wrenching, and that I can hardly bear the idea of leaving Aggieland.”

And then, Gates told the audience, he went for a late night walk around campus, arriving eventually at the statue of Sul Ross, the former governor and Texas Ranger and the only president besides Rudder to have a statue on the campus. He described the thoughts that raced through his mind: “ … of Ross and Rudder, of Silver Taps and Muster, of the Corps, of the incredible students and faculty and staff here, and of all that is under way to make A&M greater. I realized, sitting there alone in the dark, brushing away tears, how much I had come to love Texas A&M, all it stands for, and all it can become. And I knew at that moment I could not leave.”

- More About:

- Aggies

- College Station