It was the fourth and final hour of The Alex Jones Show, the most popular conspiracy talk radio program in the country, and everybody in the Austin studio was getting a little weary. As they do six days a week, Jones and his four young producers were simultaneously turning out a nationally syndicated live radio show, a streaming webcast, and a Web television broadcast. Jones sat behind a large desk covered with stacks of articles, which he and his researchers cull daily from mainstream American and foreign newspapers, alternative publications, and obscure journals. A monitor over his left shoulder showed a constant loop of images: a fighter plane, a vial of vaccine, shots of an ominous-looking President Barack Obama. The “document cam” above his head periodically zoomed in on whatever piece of paper he was reading from, to establish its provenance. Jones was talking about climate change, which he believes is based on bogus science. But unlike most people who regard global warming as a hoax, Jones regards it as part of a plan to control the global economy through a World Bank–imposed carbon tax.

Suddenly Jones had a revelation. “This is exactly what Aztec priests did thousands of years ago,” he said. “The priests were the original con artists. They knew when an eclipse was coming, and they’d say, ‘Unga munga unga bunga!’ and the sun would disappear. And the people would say, ‘Make it come back, make it come back!’ And the priests would say, ‘Build me palaces, then! I am God! I am Migumbu!’ And that’s all Al Gore is doing. He’s saying, ‘I am Migumbu! Give me millions, give me Nobel prizes! Carbon dioxide is evil! The polar bears are dying! Give me world government! I will rule you!’ And the public is all”—here he began raising and lowering his arms and chanting like a native in a King Kong movie—“‘Miguuumbu, Miguuumbu.’ ” Jones caught sight of his assistants cracking up in the control room on the other side of the studio’s large window, and he began chanting louder. “Miguuumbu! Miguuumbu!”

“That’ll be a YouTube hit, I guarantee,” said thirty-year-old producer Jaron Neihart, who wore a red hooded sweatshirt and blue jeans. The show went to commercial, and Jones stepped out into the control room, where everyone was still smiling. “What?” he asked, grinning. “What’d I say?”

Then he turned abruptly serious. “This is real,” he told me, reverting to his booming on-air voice, which was oddly discomfiting in the close confines of the control room. “They are openly calling for global government. Somebody pull him up that Al Gore quote about Copenhagen.” (An international climate change summit was meeting in Copenhagen that week.) Neihart moved toward one of several desktop computers in the control room, but Matt Ryan, a heavyset 27-year-old with sideburns who had been running the cameras during the broadcast, knew the quote and had the segment cued up on YouTube in seconds. “One of the ways it will drive the change is through global governance,” Gore’s talking head said. Neihart shook his head.

Ryan was the new guy. He had answered a Craigslist want ad six weeks earlier looking for a radio producer for an unspecified program. “If I put my name in the ad, I’d have fans lining up out the door to apply,” Jones told me. (The location of Jones’ studio is a carefully guarded secret.) When he applied, Ryan was a casual listener of the show who enjoyed Jones’ style but thought the subject matter was “a little out there.” After a few weeks immersed in Jones’s world, however, he was a believer. “If you saw what we see every day—fifty to a hundred articles all calling for global government, for eugenics, mind control, and everything else—you’d believe it too,” he said.

Regardless of the day’s news, the big picture for Jones is always the same: A fascistic cabal of powerful corporate interests and politicians is secretly (or sometimes not so secretly) building a global government—the New World Order, for short—bent on controlling the world’s population. It’s an updated incarnation of an old idea, and the enemy has gone by many names over the years: the Bilderberg Group, the Trilateral Commission, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Illuminati.

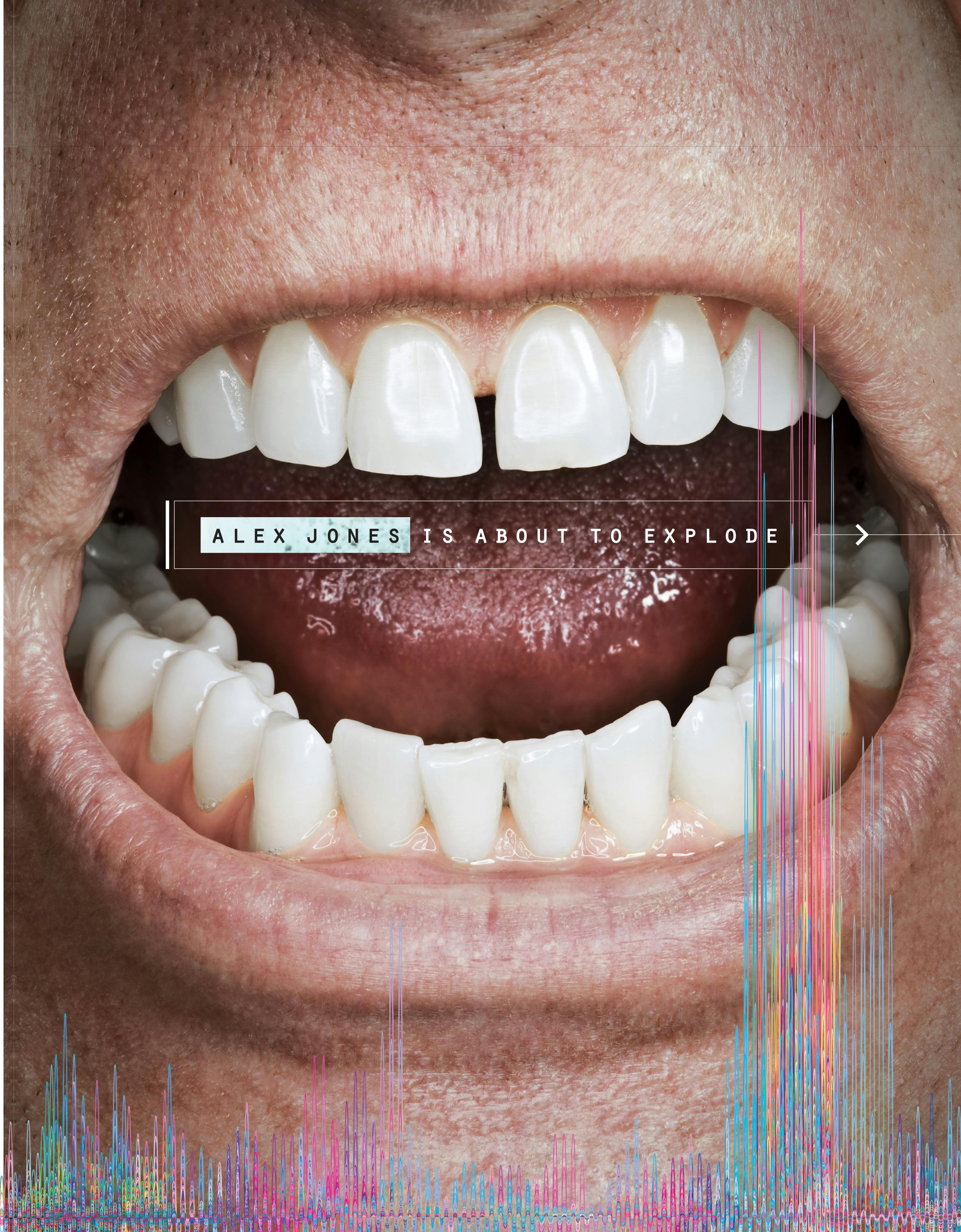

What really sets Jones apart is not the message itself but how good he is at delivering it. The 36-year-old Jones has a charismatic, commanding presence that belies his relative youthfulness and a booming voice that was tailor-made for radio. He is also a relentless and creative entrepreneur who has deftly managed to spread his brand across a variety of platforms. The Alex Jones Show is syndicated by more than sixty stations and heard weekly by 2 million listeners. Jones’s two main Web sites, Infowars.com and PrisonPlanet.tv, draw 4 million unique users, more than Rush Limbaugh’s site. Unlike Limbaugh or other talk radio stars, Jones appeals to a young demographic; he’s a cult favorite on college campuses, and his rants are all over YouTube. His documentary films, which he produces at the rate of nearly two a year, have been viewed millions of times online. After Jones announced a contest to see who could distribute the most copies of the infamous poster of Barack Obama done up as the Joker, the image became ubiquitous, appearing not only at tea party rallies but on T-shirts and street corners around the world.

At a time when the national conversation has expanded to include talk of government “death panels” and the legitimacy of the president’s birth certificate, The Alex Jones Show seems to have captured the national zeitgeist. The biggest hero of the tea party constituency is Ron Paul, the maverick Texas congressman who has long argued, as Jones does, that both the left and the right are corrupt. Suddenly Paul’s name is all over the mainstream media. But Jones has been singing Paul’s praises and interviewing him on the show for years, and that gives Jones grassroots credibility—though even Paul considers many of Jones’s views beyond the pale. If Scott Brown’s stunning Senate victory in Massachusetts signals that a new populism has arrived, then perhaps Jones’s moment has arrived too. Starting out fourteen years ago with nothing but a cable-access TV show, he now employs fifteen people in his 7,600-square-foot headquarters, which features a state-of-the-art radio studio and video editing suite. And he’s not stopping there: A TV studio devoted to his Web broadcasts is in the works.

“We’re about to explode,” Jones said.

Jones climbed into his brand-new Dodge Charger and fired up the enormous engine. He had been to a Megadeth concert over the weekend—lead singer Dave Mustaine, a fan, had invited him—and the satellite radio was set to a heavy metal station. Megadeth named a recent album after Jones’s 2007 film Endgame: Blueprint for Global Enslavement. “I think it’s my best film,” Jones said. “With the New World Order, the global government’s only the beginning; once they get that in place they’re going to start an orderly extermination of the population.” Jones believes that the eugenics movement, the theory and practice of racial purification that began in England in the 1880’s and reached its apotheosis in Germany under Hitler, never really died but instead went underground and resurfaced in such modern institutions as Planned Parenthood and the environmental movement. The ultimate goal of the New World Order, he argues, is to eliminate 80 percent of the global population—people the elites regard as nuisances who use up too many resources.

Jones recognized an Iron Maiden song from his youth. “Die with your boots on, baby!” he shouted. We fishtailed out of the parking lot and onto a highway access road, and Jones got the ridiculously overpowered car up to 80 in seconds.

Jones turned the music down. He seemed exhausted, but he was having trouble unwinding. “I always enjoyed doing radio, but sometimes I dread it now. Oh, my God. Just piles of evil, piles of quotes and documents, all total proof of their corruption, and I don’t even have the will to look at it again.”

Then, almost as if he couldn’t help himself, he was off on another rant. “The worst of the worst, the most corrupt, the most sadistic, the most bloodthirsty, the biggest control-freak, obsessive-compulsive nutcases run things. And they want to run everything; they get off on it. And the problem is, good people don’t get off on that. So we’re at war against a guild of control freaks and perverts and sickos who relish conning people and relish lying and relish spreading misinformation and relish propaganda. They have openly written one-thousand-plus white papers and hundreds of books about their plan, and I’m over here going, ‘Look at this, ladies and gentlemen!’ ”

We stopped at a nearby coffee shop, where a shy young man approached us.

“Hey there, buddy, what’s your name?” Jones asked.

“Daniel.”

“Nice to meet you, buddy.”

“I’m a three-year listener. I think the world of you.”

“Awesome, bro, good to meet you,” Jones said.

Jones, the son of a dentist and a homemaker, grew up in the Dallas exurb of Rockwall and moved to Austin in 1991, where he attended Anderson High School. Jones describes himself as a “socially oblivious” teenager who was more of a reader than a TV watcher. But when he came across C-SPAN’s 1993 coverage of the congressional hearings on the Branch Davidian tragedy in Waco, he was hooked. “It was like my soap opera. Hours and hours and hours of it on television,” he said. Investigators eventually concluded that the Davidians, not the federal authorities, started the fire that destroyed their compound at Mount Carmel and killed 75 people inside, but the hearings nevertheless exposed plenty of holes in the official story of the standoff, and the FBI and the ATF did not come off well. On the far right, Waco rapidly became a symbol of a federal government run amok. (The Oklahoma City bombing occurred on the second anniversary of Waco.) Mount Carmel was also becoming another grassy knoll for a new generation of conspiracy theorists. “I learned that there was an agenda, there was manipulation, there was deception,” Jones said. “I didn’t know what the full agenda was, but I wanted to find out.”

Jones began looking for an alternative to the mainstream media and found it on access television. The early nineties was a golden era for Austin’s cable-access station, Austin Community Television, which was becoming nationally known as an incubator of talent. Richard Linklater’s Slacker and Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi, two of the seminal works in the budding independent film movement, were edited using ACTV facilities. Jones became a devotee of the station’s independent news program, Alternative Views, which featured government whistle-blowers and other guests from the left side of the political spectrum. He got his own show in 1996, after leaving Austin Community College without a degree. His message wasn’t as refined as it would become, but his talent was obvious, and so was his passion. Jones began appearing at public hearings, cameraman in tow, and buttonholing politicians like Austin congressman Lloyd Doggett, whom he ambushed with a series of questions about thumb-scanning devices and national ID cards. “You’re selling this country out!” he shouted at a wide-eyed Doggett. Eventually he realized he was screaming a little too much. “Once, I got so excited I was spitting up blood,” he told me. He learned to moderate his outrage, preserving his velvet baritone.

Jones’s fan base grew, even when people weren’t sure what exactly he was so excited about. In 1997 he got a weekend talk radio gig on an FM station in Austin. (Ahead of the curve, he also began broadcasting from a home studio to several small satellite networks around the country. It was niche radio—you had to have a satellite dish to listen to it.) Talk radio was blossoming all over the country, and Jones began appearing as a guest on other shows, until he had done literally thousands of interviews, honing his message and spreading his name. In 1998 he became one of the first voices syndicated on the new Genesis Communications Network, which brought his show to a much wider audience. Almost overnight, he was on a hundred stations. He was doing three hours of radio a day, then rushing over to the ACTV studio to do his TV show three nights a week and making movies on the weekends. “He pretty much dominated ACTV by that point,” his longtime friend and colleague Kevin Booth recalled. “It was all about who had the most popular shows, with the best programming, and Alex was the king.” He was becoming a celebrity in Austin, and so many fans were coming to his tapings that he rented his own studio space to get some privacy.

“Alex’s mind is a turbocharged research and information processor, and he’s a really gifted, articulate communicator,” said Richard Linklater, who was an early fan and eventually put Jones in two of his films. “But I think his appeal is largely based on his passion. Most people struggle to articulate all the swirling overabundance of information out there and aren’t that passionate about anything, but Alex pulls it all together for a lot of people.”

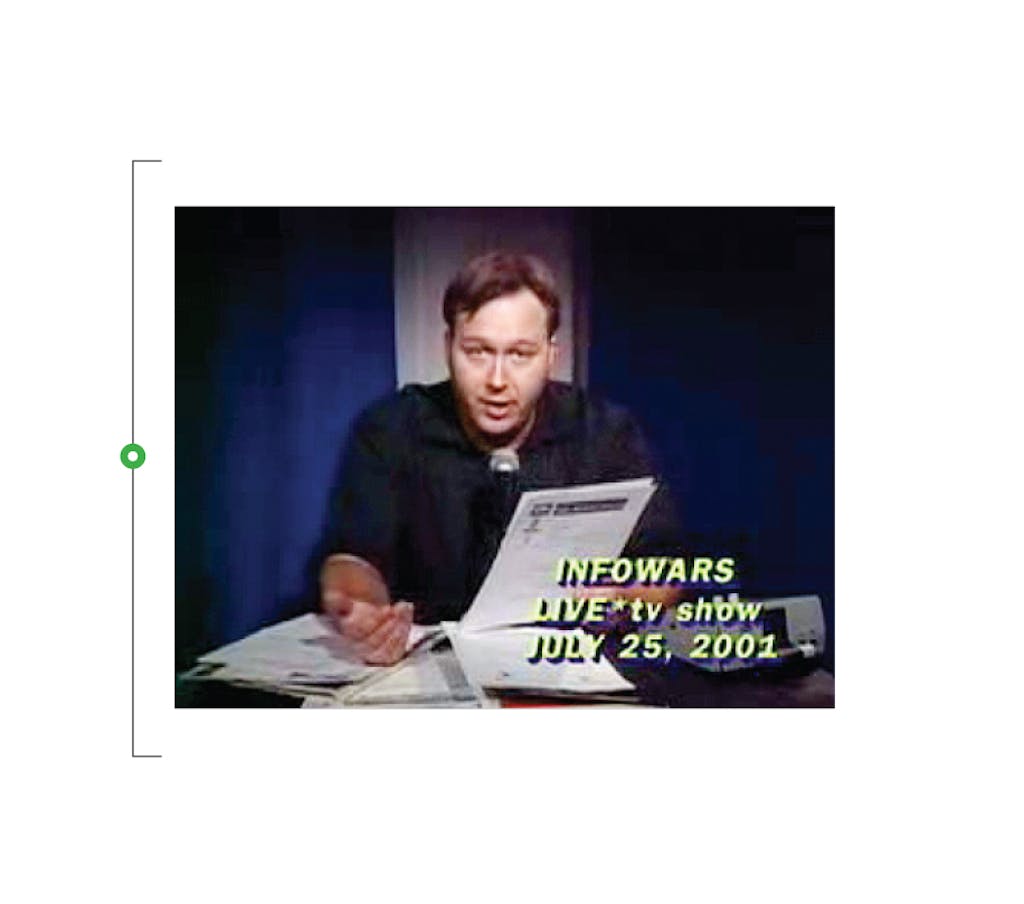

Then came 9/11. During the July 25, 2001, edition of his ACTV show, Jones predicted that the government  would stage a major terror attack inside the United States and blame it on someone like Osama bin Laden as a pretext for ushering in a police state. Six weeks later, when the planes hit the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Jones immediately announced that the attack was an inside job. Almost overnight, three quarters of the stations carrying his Genesis show dumped him. But Jones refused to back down from his claims, and his show began to attract others who questioned the official story. Skeptics argued, for instance, that the damage caused by the exploding planes could not have caused the towers to collapse, which meant the buildings must have been wired for demolition. The July 25 clip went viral on the Web, and Jones became known as the man who “predicted 9/11.” He organized and spoke at the first 9/11 truth conference, held in Los Angeles in 2007. After an introduction by Charlie Sheen, a 9/11 skeptic who called Jones a “great American patriot,” Jones gave an electric speech to a packed auditorium. What had seemed like a devastating mistake only a few years before had become the defining moment of Jones’s career.

would stage a major terror attack inside the United States and blame it on someone like Osama bin Laden as a pretext for ushering in a police state. Six weeks later, when the planes hit the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Jones immediately announced that the attack was an inside job. Almost overnight, three quarters of the stations carrying his Genesis show dumped him. But Jones refused to back down from his claims, and his show began to attract others who questioned the official story. Skeptics argued, for instance, that the damage caused by the exploding planes could not have caused the towers to collapse, which meant the buildings must have been wired for demolition. The July 25 clip went viral on the Web, and Jones became known as the man who “predicted 9/11.” He organized and spoke at the first 9/11 truth conference, held in Los Angeles in 2007. After an introduction by Charlie Sheen, a 9/11 skeptic who called Jones a “great American patriot,” Jones gave an electric speech to a packed auditorium. What had seemed like a devastating mistake only a few years before had become the defining moment of Jones’s career.

Jones is by far the biggest star on the Genesis Communications Network, a small syndicator based in Minnesota that carries a lot of conspiracy talk radio. Genesis is owned by Ted Anderson, who created it in 1998 as a way to promote his company, Midas Resources, which sells gold and silver coins to collectors and investors. Anderson appears frequently on The Alex Jones Show to remind everyone of the value of gold in uncertain times and to announce special deals for Jones’s listeners. Long before the current recession, it had been conventional wisdom among Ron Paul conservatives that the U.S. economy was a house of cards and that investing in gold was much safer than the stock market, real estate, or other commodities in general. (It is also conventional wisdom that gold is an easy sell to talk radio listeners. The owner of Anderson’s competitor, the Republic Broadcasting Network, runs a precious metals business too.) Though the number of radio stations airing Genesis shows has grown considerably in recent years, the network still doesn’t make Anderson much money, if any. It remains essentially a bullhorn for Midas Resources, which reported sales of $8.5 million last year.

The next logical step for Jones would seem to be a contract with Premiere Radio Networks, a subsidiary of San Antonio–based Clear Channel Communications, which syndicates some of the biggest names in talk radio, including Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, and Glenn Beck, and has a knack for plucking fresh talent from the wastelands of AM obscurity. In 1998 Premiere picked up Coast to Coast AM, a strangely addictive late-night call-in program for mavens of UFOs and other paranormal phenomena. The show became a huge hit, carried by hundreds of stations, and the hosts, first Art Bell and now George Noory, became highly paid stars.

There’s no question that Jones is as talented as Bell or Noory (he occasionally appears on Noory’s show as a guest), and Jones says that he has been offered big money to take the next step. So why hasn’t he? Jones told me he was worried about losing editorial control of his show or having to move to a major market in order to have access to the big-shot guests. “I wouldn’t be comfortable with a fifty-million-dollar contract with Fox News, living in New York or L.A.,” he said.

In any case, Jones may not need Clear Channel. He may never become a household name like Glenn Beck, but he has developed a business model that works for him. Jones told me that his total revenue last year was about $1.5 million. Much of that money comes from banner ads Jones sells on his Web sites, along with audio ads on the Web stream and podcast versions of his show. Most of the products advertised are in the survivalist vein: freeze-dried food, water filters, shortwave radios, seeds. (Jones does old-fashioned, Paul Harvey–esque pitches for his sponsors: “What are you going to need? Food. How much? As much as you can get!”) He also sells his DVDs, Infowars T-shirts, and books and videos from other personalities in the “truth” and “patriot” movements. On one of his sites, PrisonPlanetTV, paid subscribers can watch live broadcasts of the radio show, à la Howard Stern. Jones puts much of his earnings back into his expanding business, but he has also achieved a level of comfort that is impressive for a self-made man. In 2007 he bought an $800,000 house in a gated community west of Austin.

Jones seems to genuinely love doing things his own way. Despite the doom and gloom of his message, his headquarters isn’t a depressing place. Spending time there is like taking a trip to Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, a place full of young people playing with gadgets, overseen by a quixotic boss who isn’t much older than they are. Jones spotted my miniature Flip Video camera one afternoon and immediately got excited. “Let’s get everybody one of those,” he told one of his guys. “I’m so tired after the show, but when I get home and get my energy back, I can shoot something and put it up on YouTube.”

Jones, who started out on cable access so that he could use the free equipment, can now buy anything he sets his sights on. He has essentially built his own ACTV station, but better: Now he’s the boss, surrounded by people who love and admire him. As he has become something of a celebrity in his own right, Jones has met many famous people, and he likes to include short interviews with stars like Willie Nelson and the comedian Joe Rogan in his films. But he seems more comfortable around his own crew. “I don’t like worldly people,” he told me, “people that get off on owning things. It’s a narcissism.”

The best catalog of the evolution of Jones’s craft—and his message—is his documentaries. In the 2000 film Dark Secrets, Jones sneaked into Bohemian Grove, the private retreat deep in the redwoods north of San Francisco, where an exclusive club of powerful men (women are not allowed), including various presidents, visiting dignitaries, and captains of industry, have met annually for decades to network and recreate in posh campgrounds stocked with hundreds of servants and a great deal of booze. Jones managed to capture the first-ever footage of the club’s bizarre opening ceremony, which features priestlike figures in colored robes, a giant stone owl, and the sacrifice of a human figure, all conducted by torchlight beside a lake covered with spooky fog. In the film’s introduction, Jones seems to question whether the sacrifice he witnessed was merely symbolic, referring to it as a “so-called” mock sacrifice. (“Whether it was an effigy or real, we do not know,” promotional material for the film reads.) As hokey as the presentation is, the creepiness of it all certainly comes through, and you have to wonder, “What the hell are these people doing?”

The problem is that Jones knew perfectly well what they were doing, because the definitive exposé on Bohemian Grove had already been done eleven years before, by Philip Weiss, a writer for Spy magazine, who repeatedly infiltrated the grove over the course of three weeks. As Weiss reported, the victim in the opening ceremony, called the “cremation of care,” is not a real person but an effigy meant to symbolize the worries and burdens of the attendees, who are encouraged to spend their time in the grove doing no work, only relaxing and drinking. The ceremony was cooked up more than a century ago, when it was fashionable for secret societies in America—like the Masons, the Odd Fellows, and the Greek social fraternities—to claim a ritual that connected them to the Old World. Everybody gets in on the fun. The year Spy visited, the voice of the giant stone owl was provided by Walter Cronkite.

Of course, when this many powerful people get together, work does get done, and here’s where the Spy story makes Jones’s point—that powerful men meet in secret to plan the future of the world—better than his own film. Weiss reported that a litany of guest speakers had come to pitch the club’s influential members. A general from the Pentagon talked about the importance of funding the B-2 stealth bomber. An Associated Press executive made a plea for a reporter held hostage in the Middle East. Weiss managed to get an audience with a visiting Ronald Reagan, who confirmed that it was at the grove that he and Richard Nixon decided which of them would be the Republican nominee for president in 1968.

When I made this point to Jones, he conceded that if he could do it over again, he would focus more on the deal-making going on inside and less on the occult. He also insisted that he never meant to suggest that he had witnessed an actual human sacrifice. “I was twenty-five years old,” he said. “Now I’m thirty-five. I’ve grown more reflective.” This explanation would be easier to swallow if Jones hadn’t issued a recut of the film in 2005, with a new mini-feature tacked on called “The Order of Death.” Still, there’s something unfair about attacking Jones for sensationalizing the Bohemian Grove story when so much of what passes for news today is tawdry fluff. Would 20/20 have approached it any differently?

The production values of Jones’s films have greatly improved over the years; 2007’s Endgame has an impressive original score and plenty of Ken Burns—style archival footage and photo stills. But, as in the Bohemian Grove film, the thinking is muddled at best, and Jones proves to be his own worst enemy. Endgame, a would-be exposé of the modern eugenics movement, bogs down when it focuses on Jones raising hell outside a meeting of the Bilderberg Group in Ottawa. A crowd of twenty protesters cheers as Jones bullhorns on the street outside the conference, and there is much excited comparing of notes about which world leaders and power brokers have been sighted driving by and entering the hotel. But what exactly is being exposed? It’s no secret that Bilderberg, a conference of prominent political and business figures, has met every year since 1954. The footage reaches a low point in an interview with a French Canadian boy who tells the camera in choppy English how he and a friend spotted the ninety-year-old David Rockefeller, said to be the mastermind of the New World Order, on his way to the conference. “We yelled, ‘Hey, Rockefeller!’ ” he says, laughing. “And he was afraid.”

Endgame offers the fullest explication of Jones’s theory about eugenics, based in part on a lengthy 1974 memorandum by then National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger. In the paper, Kissinger argues that overpopulation in the Third World is a threat to global stability and contemplates withholding food aid to countries that fail to take proactive steps to address the problem, such as family planning. Kissinger has been called an amoral monster many times, and this proposal, which is authentic, doesn’t help his legacy any. But anyone who reads the entire memo will see that Kissinger himself didn’t think such coercion was a good idea (though his objections were practical, not moral: “Successful family planning requires strong local dedication and commitment that cannot over the long run be enforced from the outside,” he wrote). And it wasn’t just the secretive National Security Agency that was worried about overpopulation; the bulk of the ideas in the report mirror strategies proposed in a United Nations population control plan, which was publicly debated that same year, in the wake of widespread famine in Africa and Asia.

The biggest problem for Jones’s theory of a global eugenics conspiracy is the historical record. Take India, for example. Organizations such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the World Bank have funded enormous agricultural and infrastructure projects in India, increasing food production and building dams and highways that have helped bring the country into the industrialized present. These innovations have been criticized for saddling India with debt and environmental problems, but they hardly jibe with Jones’s notion that the globalists are trying to reduce the population and limit industrial development in the Third World.

Endgame relies heavily on guilt by association, a common device in conspiracy theory. Consider Jones’s contention that Planned Parenthood is part of a modern-day eugenics campaign. It’s true that Margaret Sanger, the intellectual founder of the birth control movement in America, endorsed eugenics when the idea was common currency, in the twenties and thirties (so did Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, and John Maynard Keynes, among other prominent figures). But as any serious examination of Sanger’s career makes plain, the birth control movement grew out of the drive for women’s liberation, not a desire to purify the race. Tying modern Planned Parenthood to eugenics because of Sanger’s seventy-year-old writings is like saying that today’s Democratic party, the party of civil rights, is a racist organization because most of the men who founded the Ku Klux Klan in the 1860’s were Democrats.

After a few weeks of watching Jones’s films and listening to his radio show, it’s hard not to ask: Can he really believe all this? The trouble with doing four hours a day of conspiracy talk radio is the same faced by all talk show hosts: You need a constant supply of grist for the mill. People will only listen to you talk about Waco and 9/11 for so long. Thus everything becomes fodder for the show, and everything has to fit into the overarching theory. The earthquake in Haiti. Hurricane Katrina. The shootings at Fort Hood. The swine flu vaccine. Global warming. Jones has been doing this for so long that he seems unable to stop. Over a beer, I asked him what he thought of Paul Wellstone, the progressive U.S. senator from Minnesota who died in a plane crash in 2002. Jones nodded with approval. “He was against the Iraq war when the establishment was attacking anyone who dissented.” Then he said, “Government killed him for sure. The FBI got to the plane first. The thing about it is their bodies were touching metal when they found them.” I looked at him blankly. “Microwave gun,” he explained.

Nothing offends Jones more than the suggestion that he just pulls stuff out of the air. “You haven’t read the documents I have,” he told me time and time again. Jones does employ several researchers, and almost everything he says is grounded in some objective fact, however far removed from his on-air assertions it may be. When I scoffed, for example, at his claim that Monsanto, the giant agribusiness company, was intentionally killing people with its genetically modified crops, he sent me several articles from mainstream publications, one pointing to organ failure in rats fed Monsanto’s corn and another outlining the revolving door between Monsanto’s upper management and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which has consistently declined to regulate genetically modified foods. None of it was news to me—the Sierra Club, which Jones regards as an agent of the New World Order, has been warning people about genetically modified crops for at least ten years. But where the Sierra Club argues that Monsanto is ignoring the potential danger to humans and the environment in its drive for profit, Jones argues it’s doing so because it wants us dead. When I suggested to Jones that people would be more likely to listen to his ideas if he didn’t tie everything to his theory about the New World Order, he wouldn’t have it. “They’re not doing it to make money, Nate. Wake up and listen to what I’m saying.”

Jones can be confrontational and dismissive, but he also has an oddly childlike manner that surfaces from time to time. After a lengthy and contentious interview one afternoon, he called me back a few hours later. “Do you think what I’m doing is bad?” he wanted to know. “Do you think I’m a bad person?”

Jones is also capable of laughing at himself. A few years ago he recorded a “don’t talk during the movie” public service announcement for Austin’s Alamo Drafthouse theater chain in which he parodied his own persona. “We’re going to find out who these talkers are, we’re going to find out where their funding comes from, and we’re going to shut them down!” he shouted. Candid video of Jones shot by his friend Kevin Booth likewise shows a side of him that rarely surfaces on the radio. After the Bohemian Grove exposé came out, Jones and Booth returned to the area, and Booth filmed Jones goofing off near the entrance and then driving through the dense redwood trees nearby. With the tape rolling, Jones pulls over to ask a middle-aged man and woman standing by an old, tarpaulin-covered pickup on the side of the road what they think of Bohemian Grove. It immediately becomes apparent that the woman is deranged. “Is that an electric eye?” she asks, looking into Booth’s camera. As they pull away, Jones is clearly delighted that Booth got the encounter on tape: It was another classic access-television moment. “You’re beginning to sink deeper into the rabbit hole now,” he says as Booth giggles. “This is like a Lovecraft novel: You have, like, this enslaved mass of gibbering creatures—most of them you will find are gibbering—and then you’ve got the world leaders.”

There has always been a tension, even in Jones’s public persona, between the iconoclast and the entertainer. “To me, Alex is funny,” said Booth. “He has that Orson Welles showmanship. He’s funny on a different level, even when he’s not really trying to be funny.” Booth, who grew up with the late Texas comedian Bill Hicks and produced his comedy recordings, once thought of Jones as the natural heir to carry on Hicks’s legacy. Hicks’s act was dark and overtly political, and like Jones, he was tormented by what happened at Waco. In 2000 Booth culled some of the most confrontational and outlandish moments from Jones’s access show and produced a low-budget video called The Best of Alex Jones. “I thought that I was going to introduce Alex Jones to all the Bill Hicks fans and they were all going to love him,” Booth recalled. “They thought that I had completely lost my mind.”

Booth, who featured Jones in his new medical marijuana documentary, How Weed Won the West, still thinks there’s a market for the lighter side of Alex Jones. He recently created a trailer for a reality TV show—a sort of “Day in the Life of Alex Jones”—that he has been shopping to producers in Hollywood. “It was going to show the crazy world of Alex Jones and not be so much about the conspiracy theories,” Booth said. Nobody bought it. Like Hicks’s fans, the producers didn’t seem to see the side of Jones that Booth saw. “They said, ‘If Alex Jones is going to be funny, we need to see it.’ ” To add insult to injury, TruTV recently launched a reality show called Conspiracy Theory, with Jesse Ventura, a frequent guest on Jones’s radio show. Jones, who is a paid consultant to Conspiracy Theory and has appeared on the show, told me he wishes Ventura well. But the topics Ventura covers—9/11, the New World Order, eugenics—are right in Jones’s wheelhouse. Ventura is clearly stealing his thunder.

“I would just love to be able to see Alex breaking through to the mainstream,” Booth said, though it might mean moderating his message somewhat and losing some of his longtime fans. “I think Alex fears that if he suddenly kind of lets his hair down a little bit those people are going to think that he’s a traitor or that he was full of shit all the time, that he didn’t really mean it. I think he fears that his fans won’t love him anymore.”

Of course there’s nothing funny about America being taken over by a fascist dictatorship bent on killing most of the population. Now that Jones has become a guru to so many, can he have it both ways? Can he laugh at himself without laughing at his audience too? Jones didn’t want to talk about the reality show trailer. “Kevin Booth is always pitching shows to producers in Hollywood. It’s what he does,” he said. “It’s a non-issue.” And he was offended by the notion that there might be a different Alex Jones hidden beneath the one his listeners hear every day. “I’m real, okay?” Jones said. “I’m real. I don’t want my own TV show. I’m happy with what I’m doing. I don’t want stardom. That’s what you don’t understand about me.”

By dint of his show’s success and longevity, Jones has become an establishment figure in his own anti-establishment movement. There are now conspiracy theories on the Web about Jones himself: that he is a CIA agent, a cog in a Jesuit conspiracy (with Charlie Sheen), or a Zionist, out to cover up the secret Jewish role in the September 11 attacks. “It’s all complete hogwash,” Jones said. More troubling, he told me, is the way personalities at the top of the media food chain have been co-opting his message. Glenn Beck is the worst, he said. “Two weeks after I have a guest on, they have him on. Three weeks after I play a video on air of George Bernard Shaw saying, ‘If you’re not productive in society, then the socialists are gonna kill you, and Hitler is good,’ he’s playing it on his show,” he said. “We fished that out. We got that from a European filmmaker. It’s like we’re programming their show. Beck says, ‘It’s not about a Democrat, it’s not about a Republican; we’ve got to change the paradigm.’ He says all that, but then he says, ‘But the Republicans are going to save us.’ Glenn Beck is literally word for word taking everything I do and twisting it and turning it into a Roger Ailes Fox News evil doppelgänger of my show,” he said.

Jones sees the same thing happening to the tea party movement. “The tea parties were started by 9/11 truth groups, going out and protesting and calling people out. And then you had the Ron Paul Revolution in 2007, 2008. And by early 2009 you would have Rick Perry or John Cornyn giving a speech and they would be booed by the tea party people. But the media wasn’t reporting on that. MSNBC and others were saying it’s all orchestrated by Republicans.” It became a self-fulfilling prophecy, Jones said, as Glenn Beck and Fox News began sponsoring their own tea party events. “It’s very simple: The Republicans are out of power, so they can now play the part of the rebels. They’re trying to ride the coattails of this populist uprising and co-opt it.”

If this uprising seems more than a little paranoid, that’s hardly a new phenomenon. What the historian Richard Hofstadter once called “the paranoid style” in American politics seems to be waxing again, and it brings with it a fundamental problem for our national politics: How can we have a meaningful dialogue if we can’t even agree on basic facts? Was President Obama born in Hawaii or wasn’t he? Will the health care reform bill establish “death panels” or not? Can burning jet fuel melt metal structural beams or can’t it?

But Jones and his ilk didn’t create this crisis of credibility. Jones’s younger followers, after all, came of age hearing Colin Powell assure the UN that Saddam Hussein tried to purchase uranium in Niger, though the evidence was shaky at best. Or Dick Cheney desperately trying to tie Hussein to the 9/11 attacks, despite all evidence to the contrary. Or the president of the United States assuring the world that we knew Iraq was hiding weapons of mass destruction, only to find out it wasn’t true after thousands of lives had been lost.

Still, plenty of people who are appalled by such deceptions can’t bring themselves to follow Jones all the way down his rabbit hole. His refusal to moderate his message means he has, in effect, limited the trajectory of his own career. But Jones told me he doesn’t care if he’s not taken seriously today. “I care about people seeing what I said in twenty years and saying, ‘Man, that guy was right.’ Because that’s a time bomb for the enemy. People are still in denial today, but decades from now the information that we put out will be so accurate that it will be taken like revelation. And so even if they set me up, kill me, it won’t matter, because it was about the information. And even if they destroy me, they fail in the end.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Conspiracy Theories