This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

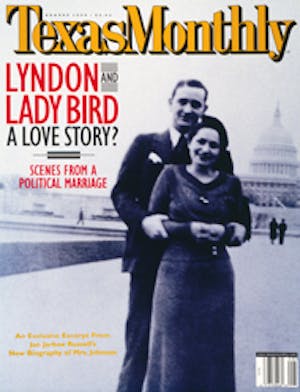

On November 18, 1934, the day after their wedding, Lady Bird and Lyndon Johnson drove from San Antonio to Monterrey, Mexico. The decision to go there for a honeymoon was mutual, but it was perfectly suited to Lady Bird’s taste. The red hibiscus blossoms, the broad-leafed banana trees, the impromptu serenades—not to mention the favorable exchange rate, making every purchase seem like a fantastic bargain—all combined to make Monterrey a natural place for Lady Bird’s transition from life on her own to Johnson’s strange new world.

The following day, they boarded a train to Mexico City. From the train, Lady Bird’s eye was continually drawn to the hundreds of shrines to the Virgin Mary that had been built along the winding roadways. As a Protestant, she was unfamiliar with the role that the Virgin Mary occupies as the embodiment of the ever-present merciful mother to Roman Catholics. “Those places by the side of the road seemed so strange to me,” she recalled. “I don’t know why, but the sight of little girls laying paper flowers at the shrines is one of the strongest memories I have of my honeymoon.”

She tried to engage Johnson in conversation about the shrines, but he wasn’t particularly interested in Mexico. Mentally, he was back in Washington. He spent most of their honeymoon talking about his work. “I heard a lot of big talk about how he wanted to be the best, hardest-working congressional secretary in Washington,” she recalled. He missed his friends and the round-the-clock action on the Hill. “I was a born sightseer,” Lady Bird said with a sigh, “but Lyndon was a born people-seer. He indulged me on that trip, but the truth is he wasn’t much intrigued.”

In Washington they moved into a modest one-bedroom furnished apartment at 1910 Kalorama Road. There, Lady Bird, who had never swept a floor or cooked a meal, set about trying to learn how to be a housewife. She, who had been waited on all her life by maids, now filled her days and nights waiting on Johnson.

He expected to be served coffee in bed every morning, along with the morning newspaper. He also expected her to pay the bills, to take care of his clothes, and to have meals ready at all hours of the day and night in case he or any member of his staff showed up hungry. When asked if she resented doing any of these chores, Lady Bird said, “Heavens no. I was delighted to do it. I adored him.”

In public Johnson often treated her as if she were invisible. Sometimes he would tell negative stories about her—about how she kept house or how she pinched pennies—in front of her in a group. “I thought if we went to a party, Lyndon would be with me the whole evening. He wasn’t. At first I was incensed. I was left alone with a bunch of strangers,” she recalled. Instead of showing her anger, Lady Bird realized that either she would have to work hard to win over Johnson’s friends, to become part of the circle, or she would have to reconcile herself to staying on the fringe.

During the day, she worked hard to take care of the chores at home as quickly as possible so that she could prowl around Washington on her own, often with a camera. She thought of herself as an explorer and wanted to document the places and events around her in photographs. Neither housework nor shopping held any interest at all for her.

She was ambivalent about her own wardrobe. Her lack of interest in clothes was one the few concrete expressions of her desire for some degree of independence from Johnson, who pushed her to look a certain way—even to the point of humiliation. He wanted her to look respectable but sexy. He liked bold colors—red, blue, green, and black—and straight skirts, not flared or pleated. If she walked into a room and she wasn’t wearing lipstick, he would bark, “Put your lipstick on. You don’t sell for what you’re worth.” If he thought her hair was too long or too short, he would order her to have it cut or let it grow. If some other woman was wearing a dress he liked, Johnson would point to her and ask, “Why can’t you look like that?” It was his bellicose way of talking, the kind of stereotypical, macho speech he had grown up with in Texas, and Lady Bird didn’t take offense.

In fact she even regarded Lyndon’s admonitions on clothes as backhanded compliments. “He thought I was good-looking and he wanted others to see me that way,” she explained. She viewed it as an indication that he was interested in her. “I had the idea that people were supposed to love me because I had an interesting mind, a kind heart, and a warm smile. I thought that Lyndon’s emphasis on clothes and appearance was the wrong system of values. He used to say that a lot of the people that I met would only see me once, and that the opinion they would form would persist. He wanted them to have a good opinion of me. By the world’s rules, he was right. I was wrong.”

One evening they went to see the movie version of John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath. In the darkness of the theater Lady Bird heard Johnson sniffling. Moments later she heard loud sobs. The story of the Joad family reminded him of his own family’s poverty. Lady Bird was astonished that he was able to express such strong emotion over a movie. She grabbed his hand and squeezed it, both proud of him and puzzled. “He had a tender, sentimental side that he didn’t show very often,” she recalled.

She also remembers her long waits for him to come home. Night after night she would stand by her kitchen window in their first Washington apartment, watching for the headlights of his car as he pulled in. “He would run through the door and grab me into his arms,” Lady Bird recalled. “It was the highlight of my day.”

There were other, far more overt strains on the marriage, tensions that Lady Bird could not alleviate. Around 1937, Johnson began an affair with Alice Glass, whom Lady Bird had known briefly at the University of Texas. Born in the Central Texas farming community of Marlin, Alice was almost six feet tall with honey-blond hair and blue eyes. Her long affair with Johnson has been written about by Robert Caro in Path to Power and also in a memoir published in 1993 by former Texas governor John Connally, Johnson’s closest political adviser.

Like most affairs, the one between Alice Glass and Lyndon Johnson was a web of intrigue, fraught with peril. Glass was the mistress and later the wife of Charles Marsh, the wealthy publisher of the Austin American-Statesman and one of Johnson’s primary patrons. It had the potential to imperil Johnson’s marriage and his political career, a risk that he seemed compelled to take. Like other presidents before and after him, Johnson was a man who, even from a young age, was pulled in two directions at once. Part of him wanted great power for the glory of helping others on a mass scale. Another part of him wanted power so that he could satisfy rawer instincts, including his desire for random, unlimited sex and the thrill of dominating others.

On occasion, Lady Bird was forced to deal with Alice Glass and Lyndon together. These meetings occurred after Alice had moved to Longlea, an eight-hundred-acre horse farm set in the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. From Lady Bird’s point of view, it was difficult not to be intimidated by Alice. She was gregarious and openly seductive, the very embodiment of all that Lady Bird had repressed in herself. “Alice had a great presence,” said Frank Oltorf, a lobbyist for Brown and Root Construction who knew both the Johnsons and Alice. “When she walked into a room, everyone looked at her. She was tall, slim, good-looking, and extremely smart. She had a voice that was both sexy and soothing.” Oltorf believed that in Alice, Lyndon Johnson had found his match: a woman as smart and seductive as he was.

Though Lady Bird never voiced her feelings about the affair, those who were close to the situation are convinced she knew. Her reply when confronted with questions about Alice Glass has been not to reply at all and to take refuge behind an emotional wall. “I never saw that side of him,” she has said repeatedly.

However, her actions—as opposed to her words—during the time that the affair was in progress indicate that Lady Bird was neither unaware nor passive about her situation. After all, her whole mission in life—to be a good wife and eventually a good mother—was under threat. In response she did what women have done throughout the ages. First, she retreated. Her visits to Longlea became more infrequent, as she withdrew into a stubborn silence that seemed incomprehensible to those around her.

Next, she blamed herself—at least in part—for her husband’s infidelity. After the initial withdrawal, Lady Bird embarked on a frenzied self-improvement campaign, using Alice as an unconscious model for what she needed to become. She lost weight, getting down to about 115 pounds, a weight she maintained throughout Johnson’s presidency. She started wearing the sexier clothes Johnson liked. She checked book after book—including War and Peace—out of the library, steeping herself in history and the classics. She applied makeup and wore jewelry, as Alice did.

And she worked harder than ever. When constituents came by Johnson’s office, Lady Bird was often there and gave tours of the Capitol, Mount Vernon, and the White House. She also worked hard at learning the rules of social protocol. Like other congressional wives, every year Lady Bird purchased the Green Book, an updated social guide to official Washington written by Carolyn Hagner Shaw. “In those days the wives of congressmen made official calls on other wives,” recalled Lady Bird. “I had my calling cards printed up and every day I got dressed up in a hat, gloves, and a nice dress and went out to make my calls. It was like a business.”

Though the affair cooled off after World War II, Johnson and Glass continued to communicate with each other for the rest of their lives. Alice and Marsh divorced in the 1940’s. She continued to live in Longlea but fell on hard times financially. On May 26, 1971, she sent Johnson an antique brass eagle mounted on a glass base, about nine inches high with a four-and-three-quarter-inch wingspan. The eagle had reportedly been made for Thomas Jefferson as a gift from the French when Jefferson was ambassador to France. Alice had owned it for thirty years and wanted Johnson to have it in his post-presidential years. On the card that accompanied the eagle, she wrote, “For Lyndon, From Alice. Feed him properly.” She also warned him not to use his initials but to sign his name. “I never did call you LBJ; it’s too late to start now,” she wrote.

In a response two days later, Johnson wrote, “The elegant eagle on the beautiful crystal has arrived and it is all you said and more. I am prouder than you will ever know that you wanted me to have it, after its long and illustrious history which, of course, includes its thirty years with you. And I will cherish it as I do your faith and friendship. Thank you so very much and do come to see us.” He signed it “affectionately” but then closed the letter with his initials, as if trying to distance himself from her.

After Johnson died, Alice wrote a letter to Lady Bird and asked her to return the eagle. Lady Bird responded in a letter dated October 16, 1973, in which she explained how the eagle was used at the library. “Lyndon kept it on his desk at first and then we placed it in a glass and bronze cabinet in the corner of our living room,” she wrote, taking claim of her husband’s former lover’s possession.

Elsewhere in the letter, she wrote, “I know how much you must treasure the eagle, because it has given us such pleasure.” Lady Bird’s aides say that this was consistent with the way she dealt with the other women in Johnson’s life. Johnson tried to win over his political enemies by going overboard to be nice to them. Lady Bird in turn adopted the same approach with her most intimate enemies: She wooed them, bringing them into her tent.

“I would love to have you come by the ranch and/or Austin and visit,” she told Alice, but then ended the letter in an icy way that left no doubt that Alice really was not welcome. “Let me know ahead of time as I do travel a lot.” She did not even bother signing her initials. The closing of the letter reads “Lady Bird (Dictated, but not signed).”

Alice fired one last salvo. She let a member of Lady Bird’s staff know that the eagle had been a personal gift to Johnson, not Lady Bird. She wanted it back. On November 16, 1973, Lady Bird dictated another letter, telling Alice, “It will be on its way to you shortly,” and sent it back.

Three years later, at the age of 65, Alice died in Marlin, where she had moved to be near her sister and her close friend Frank Oltorf. She left the eagle to Oltorf.

Lady Bird has maintained a lifetime of official silence about Alice Glass, although she has told friends that she never really believed the rumors about Alice and Lyndon. “She was too plump for him,” she told one friend. Still, Lady Bird never forgot that eagle and the betrayal that it represented.

Some years after Alice died, Oltorf was invited to the LBJ Ranch for a small dinner party. After dinner, Lady Bird pulled him aside. She had a question for him that she wanted to ask in private.

“How did Alice spend her last days?” Lady Bird asked. Oltorf replied that Alice had died peacefully. “Good,” said Lady Bird. “That’s good.”

“Tell me,” she added, as an afterthought. “Whatever happened to that brass eagle of hers?”

Oltorf looked at her and smiled. “Don’t worry, Bird,” he told her. “The eagle landed safely on a tall bookshelf in my living room.”

By 1942 Lady Bird had been pregnant three times—each time she suffered a miscarriage. As she endured the painful cycles of pregnancy, turmoil, and miscarriage, her maternal instinct grew stronger. “I felt a peculiar sense of failure, of not being a complete woman,” she said of her inability to have children. “After each miscarriage, I felt the loss of a little being . . . of the potential for new life. It was a big psychological put-down as a woman.”

At the time, she owned a house in Washington, a two-story, brick colonial at 4921 Thirtieth Place, a few blocks off Connecticut Avenue in the northwest part of the city. The house had an attic, a basement, and a large porch in the back that overlooked a modest garden, which Lady Bird eventually filled with zinnias and peonies. J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, lived directly across the street.

She had looked for a house for five years, but Johnson had always refused to allow her to buy one—even though she had her own money. Their ideas about creating the proper setting for a Texan in Washington were in conflict. Johnson believed buying a home in Washington would make him appear less of a Texan to his Austin constituents. During her eight years of marriage, Lady Bird had moved ten times. Politics, not business, was her husband’s real life, and one way or another, Lady Bird knew she needed to buy a permanent home in Washington.

One afternoon she and her real estate agent had confronted Johnson during a meeting with John Connally in the living room of the apartment on Kalorama Road. The owners of the house at Thirtieth Place were threatening to sell it to someone else. As Connally remembered the scene, Lady Bird was furious. She told Johnson that she was “sick of living out of a suitcase” and was in despair over her inability to have children. She told Johnson she had “nothing to look forward to but another election.”

Johnson looked at her as though she were invisible. He simply turned and resumed his conversation with Connally. Lady Bird fled from the room in tears. Johnson was surprised by her outburst of emotion. “What do you think I should do?” he asked Connally.

“Buy the damned house,” Connally said.

The next day, Lady Bird made a down payment on the $18,000 house, every penny of which belonged to her. Johnson insisted that their telephone number be listed in the telephone book, so that he would appear accessible to the general public. His number stayed listed in the Washington telephone directory until he was vice president.

Once he moved in, Johnson liked the house so much “you would have thought it was his idea from the beginning,” Lady Bird said. Years later, he always advised young congressmen to buy a home in Washington as soon as possible. “He told them it was a good investment and would make their life in Washington so much happier,” said Lady Bird. “Every time it happened, I had a good laugh.”

The acquisition of the house on Thirtieth Place gave Lady Bird an increased sense of security. “I had desperately wanted a nest,” she said. “Psychologically, I think it prepared me to have a family.”

In August of 1943 she went to her doctor and discovered that she was pregnant. The following March 19 she went into labor. “I woke up on a Sunday morning and I told Lyndon I needed to go to the hospital,” Lady Bird recalled. “He got on the telephone. I went on and got in the car, and still he didn’t come. I was tapping my foot and beginning to get mad. Finally, he came out of the house in a lope and we went to the hospital.”

He took her to Garfield Hospital in Washington, D.C., then left and went riding around in his car for hours with a political friend. Twelve hours later, Lady Bird gave birth to their first daughter, Lynda. “The Lord helped me through it,” Lady Bird recalled. She was not angry with Johnson for leaving her alone at the hospital. She saw it as an example of the difference in their personalities. LBJ could not stand to be alone—he wanted people around all the time, especially in a crisis—while Lady Bird was the opposite. She preferred to manage her pain in solitude.

Partly in an attempt to give Johnson a son, Lady Bird became pregnant again in 1945. At some point after the first trimester, she had another miscarriage—her fourth—this one due to a tubal pregnancy, the same condition suspected to have contributed to her mother’s death. Johnson was not at home when the pain began, so Lady Bird telephoned her doctor, who sent an ambulance to take her to the hospital.

“I knew that I was in a life-threatening situation,” she said of the miscarriage. “When they were putting me in the ambulance, I remember that I was glad that Lyndon and I were well-off, that we had enough money, and wondered what it would be like to be that sick without any money at all.”

At the hospital, when she was placed on the operating table, she felt as though she were falling through space and realized she might be dying. Before losing consciousness, she again returned to her financial security. She thought about a dress that she had just purchased for $90, a sum she considered extravagant. Again the thought came to her, “I’m glad I have enough.”

Johnson was telephoned and came to the hospital. Horace Busby, who had begun working for him the year before as a speechwriter, was in contact with him. The doctor who treated Lady Bird came out and said that she was losing a lot of blood and he had given her a series of transfusions. After the fact, Busby heard that the doctor had explained that he could save Lady Bird or he could attempt to save the baby. The choice was up to Johnson. “That day his true colors came out: He was utterly devoted to Lady Bird,” Busby recalled. “He told them to do whatever was necessary to save her.”

Lady Bird got pregnant a final time in late 1946. On July 2, 1947, she gave birth to her second daughter, Luci. Moments after the birth, Lady Bird remembered that the doctor lifted the baby into his arms and said, “I never thought I’d see you.”

Motherhood did not come naturally to Lady Bird. She felt guilty for not spending more time with her daughters. However, she let both daughters know that Johnson’s career was a privilege, something for them to take advantage of and learn from, not disparage. As she told Marie Smith, a reporter for the Washington Post and an early biographer, Lady Bird saw her role as a “balm, sustainer, and sometime critic for my husband” and wanted to help her children “look at his job with all the reverence it is due.” Lyndon Johnson was not the only member of the family that had power confused with love, since the message Lady Bird gave her daughters was not to expect much emotional support from their father, but to revere his job.

Russell Morton Brown, an old friend and classmate of Johnson’s during his brief stint in law school, recalled a party given by Lady Bird at Thirtieth Place at the end of the 1950’s, well after her fortune had been made. During the course of the party, Brown and LBJ stood on the sidelines and had a conversation about what Brown described as all the “self-seeking women” who threw themselves at LBJ. From the edge of the party, Brown complimented what he called Lady Bird’s “poise” and “beauty” as well as her “business sense.” He told Johnson how much she had grown as his wife, how outgoing, even glowing, she seemed that particular night. “The best day’s work you ever did was the day you persuaded her to marry you,” Brown told him.

“Russ,” Johnson told him, “I know it every day.”

Lady Bird relinquished the residue of her shyness in July 1960 at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, when Johnson was selected as the vice-presidential running mate of John F. Kennedy. At the close of the convention, Lady Bird, then 47, emerged as a public matron who understood that her place in society, one that had been assigned to her by childhood and marriage, was significant. The dominance of the men around her—her father, the boss of Harrison County; her husband, the second most powerful Democrat in America; and the young would-be president, John F. Kennedy—was absolute.

At the same time, Lady Bird understood the possibilities of her own power. By now, after 25 years of marriage to LBJ, Lady Bird knew the full mixture of his private insecurities: his rage, his stunted ego, the deep valleys of his depressions, his hypersexuality—all of which threatened his future rise to power. In the aftermath of Los Angeles, Lady Bird no longer doubted that LBJ wanted to be president. She knew as well that she could cope with the recurrences of Johnson’s inevitable moments of bad temper. One aspect of marriage is coming to grips with the insidious wreckage of another human being’s flaws. By now, Lady Bird had done that.

Besides, Johnson’s political desire gave Lady Bird power and time to learn the more difficult lessons of love and marriage, how to discover her own peace within his storms. Johnson could not afford to leave her. It would be another twenty years before America would elect a divorced man, Ronald Reagan, as president. The hard reality was that Johnson needed to remain married to Lady Bird to be president. He would continue to “collect women”—as George Reedy, a longtime staff member, put it—but he would not leave her for any of them, and he would not quit politics.

Years later, in a televised interview with her daughter Lynda Johnson Robb, Lady Bird said she regarded LBJ as “my lover, my friend, my identity.” From a chaise lounge at the ranch, Lady Bird told her daughter, “The need for women to have their individual identity belongs to your generation, not mine.” Even in hindsight, she could not acknowledge her need for a true identity. She was a married woman of the 1950’s, a member of the “silent generation.” To oppose her husband in the era of conformity would have been the equivalent of spitting at herself in the mirror.

For that reason, Lady Bird was as well suited for the pursuit of the presidency as LBJ. Then, as now, the American presidency required a husband and wife to engage in a theatrical, courtly ritual. To be every inch the national king, the president must extol, even venerate, his first lady. Unless a president gives the appearance of bowing to his wife, of demonstrating great affection, of paying her lavish public respect, he endangers his own power. The rules of the American court require that the more trouble the president gets into, the more respect he must pay his wife.

The Johnsons made comic use of this courtly ritual. At public dinners he would sometimes pat Lady Bird on her bottom or give her a big public kiss. Once, a member of the press inquired about these displays of affection, and Lady Bird sent back word that not only did the pat on the fanny not embarrass her but that she wanted more of them. “I rather like it,” she told the press.

Stanley Marcus, the chairman emeritus of Neiman Marcus, remembered that whenever Lady Bird shopped at his store, she came in with a specific amount of money to spend for herself or Lynda and Luci, and she didn’t go over it—not even as much as ten cents. If a saleslady brought in a dress that was over her budget, Lady Bird would look at it, admire it, but then say, “It’s more than I can pay. Take it out of the room.” The truth was that there were few dresses that she could not afford to buy by 1960. The company she had founded in 1942 had public assets of more than $3 million, and she controlled 52 percent of the stock. Her thriftiness was a quirk of her personality, a leftover from a childhood spent without a mother to dress her or counsel her about clothes. (Lady Bird was five when her mother, Minnie, died on September 14, 1918.)

On the other hand, she did not object to LBJ’s excesses. He often did her shopping for her and did it to suit himself. “Rather than her choose her own clothes, he chose them for her,” recalled Les Carpenter, Liz’s husband, in his oral history. “I remember once he came back from a trip to New York with about six hats for her. Now, imagine a man going in and buying a hat for his wife that she hasn’t even tried on. But he did.”

Whether she liked the hats and dresses or not, Lady Bird wore them and pretended to like them. “Mrs. Johnson would do anything, and she always acted like they were the prettiest things she ever saw, whether she thought so or not,” said Carpenter. “She’s that kind of wife—the completely loyal wife.” This was part of the accepted presumption in 1960 about what it meant to be a “loyal wife”—feigning appreciation to your husband to serve his ideals.

“The key to understanding Lady Bird,” said Busby, an old and trusted LBJ aide, “is to understand that in her mind her father was the role model for how all men are and should be. It explains why she put up with LBJ’s womanizing and why she idealized him for being a public servant. She grew up with her father and assumed all men had a wife but also had girlfriends. She didn’t attach much importance to it.”

Even though her father would soon be dead, she was still mentally trapped in his house, stuck with his way of life. By the 1960 campaign, most of the people on LBJ’s staff understood that Lady Bird and Lyndon had an informal arrangement: He did whatever he liked, and in return for being his wife, Lady Bird pretended not to notice. All unhappy wives are forced to find some ways to adapt. Lady Bird’s mother had fled to Chicago to listen to the opera, briefly back to her childhood home, and then to mental flights of fantasy. Her stepmother had turned to prescription drugs. Lady Bird was stronger and saner than both of those women. She found a more productive way to cope: She hid behind her public duties.

There was another crucial difference; Johnson did not withdraw his affection for Lady Bird. On car rides through the ranch, Lady Bird and LBJ would often kiss and hug and flirt in ways that made passengers feel like voyeurs. Especially after his heart attack, Johnson bragged about their vigorous sex life to male aides, and except for the large blocks of time that they spent physically apart, they shared the same bedroom and the same bed until they lived in the White House. In fact, Lady Bird made a ceremony out of going to bed. Every night they spent together, either she or a maid laid out LBJ’s pajamas and her dressing gown, side by side, on top of the bed. These small gestures announced in deeds—not words—that LBJ did, in fact, love her best.

At times the arrangement was a strain on everyone. At one point when LBJ was in the Senate, Busby remembers an afternoon when he, Lady Bird, a female friend, and several male staff members went for a ride around the ranch. Busby and the staff members were in the back seat of Johnson’s Lincoln, while Johnson was at the wheel, the female friend was seated in the middle, and Lady Bird occupied the passenger seat. “Johnson made a point of placing one of his hands under the woman’s skirt and was having a big time, right there in front of Lady Bird,” recalled Busby, who added that the woman slapped his hand, though Lady Bird never said a word.

This incident is a window into the darkest corner of their marriage. Johnson apparently not only had a need for other women but he also had a need to flaunt his behavior in front of Lady Bird. He could be the ultimate bad boy. In these moments, Lady Bird mentally disassociated herself from LBJ. She developed the habit of staying above it all; the more he misbehaved, the more prim and proper she appeared. “He would sometimes say cruel things to me,” Lady Bird later acknowledged. “I had more calmness and justice than he did at times.” This was how she got even with LBJ. She took the moral high ground and always stayed calm, no matter how trying the circumstance. Yet the cost of being superior was high. It kept her locked in the primary condition of her childhood: isolation.

Immediately after the 1960 election NATO parliamentarians asked Johnson and Lady Bird to fly to Paris for a NATO meeting. It was a goodwill trip, and Johnson did not want to go. A creature of legislative action, he couldn’t believe that such a trip could have any real value. However, he accepted the invitation and made a speech at the meeting’s opening session. Still he was in a volatile mood, and Busby and others who accompanied him were braced for trouble.

It came the second night of the trip. Johnson went with a large entourage, including Lady Bird, to Maxim’s for dinner. Lady Bird was seated at one end of the table and Lyndon was at the other. As the evening wore on, he started paying noticeable and inappropriate attention to the wife of a State Department official. “After a few drinks, the woman moved down and sat down on LBJ’s lap. The two of them started horsing around, groping each other. It was pretty obvious and everyone was embarrassed,” Busby recalled.

After a while a Secret Service agent told Busby to tell Johnson that it was time to go. He walked over to Johnson and told him firmly, “Mr. Vice President, we have to leave. The Secret Service will have the cars out front in five minutes.” Johnson nodded, then he and Busby went to the other end of the table. LBJ took Lady Bird by the arm and escorted her out of the restaurant. Once in the car, the Johnsons made small talk but did not mention what had just transpired.

By then the pattern was predictable: Johnson misbehaved and Lady Bird retreated behind her wall. Everyone else followed her lead. This was also part of her power as his wife. If she ignored his misdeed, everyone else was expected to do the same. Her silence had the effect of magic; it made LBJ’s indiscretions seem to disappear.

Once when Lady Bird was first lady, Helen Gahagan Douglas, the former congresswoman and onetime mistress of LBJ’s, hosted a gathering of liberal Democratic women in New York. It was a hostile crowd. Most of the women didn’t like Lady Bird simply because of the Southern way she spoke and carried herself—and because she was not Jackie Kennedy.

“I would say that more than half of them were prejudiced against her before she rose to speak,” Douglas said in an oral history. One of the women at Douglas’ table voiced the prevailing sentiment. “I just can’t bear now to hear that Southern accent,” the woman told Douglas. Douglas asked the women to ignore Lady Bird’s accent and listen to what she had to say.

The speech was a strong, intelligent defense of her husband’s civil rights policies. “Those at my table were captivated,” said Douglas. “I knew we could rely on Bird’s decency and common sense.” This decency that Douglas and others relied upon cut two ways. Decency and common sense were Lady Bird’s tickets to power, as well as her private trap.