My son, Sam, has been trying to work us into his schedule since March. As a college student—he started NYU in the fall of 2009—he always seems to have better things to do than hang with his nosy, middle-aged parents. There was the early graduation scheme, now abandoned, that required summer school in, of course, New York, and the spring break trip to Paris that I followed enviously on Facebook and Twitter (“Never travel with people richer than you are” was my favorite tweet). And then there are the part-time jobs he takes to supplement his meager parental stipend and build his résumé: last fall he worked at Tommy Hilfiger’s flagship store, where he learned to fold clothes, wore a headset like Madonna’s, and met Joe Biden; currently, he is a patients’ advocate at a huge public hospital, which he loves and which, because he loves it, prevents him from ever getting around to coming back to Houston.

So I spend a lot of time dogging my kid in cyberspace and telling myself that the fact that Sam isn’t perpetually homesick means that my husband, John, and I did our jobs well. Born in Houston 21 years ago, just as the azaleas were blooming and the oaks were pollinating, Sam is now much more interested in Bushwick and Williamsburg than the far-flung environs of his own hometown. I’m sure New York has its merits, but like all moms who proudly send their kids into the big, wide world, my hope is that eventually Sam will want to come home. “Good luck with that,” my friends say. But I’m a Texan, and therefore an optimist.

As every parent knows, kids start moving away the moment they are born. But for eighteen years, the process is incremental: sleepovers blend seamlessly into summer-camp stays, the drudgery of carpooling ends and the worry over teenage driving begins. Then comes the day a son or daughter leaves home to begin life as a grown-up, whether it’s as a college student, a soldier, or just a rent-paying resident elsewhere. For a parent, it’s a little like wading out into the ocean and suddenly discovering the drop-off, where the water is deep and the waves are high. Worse, you are supposed to swim to shore while your child heads gamely for the open sea.

At least, that was the image I carried in my head for the period between the joyous moment Sam got his fat purple acceptance envelope and the day we actually left him, alone, in New York City. Even now, I recall those last months through a watery haze. Every time I took him to Target, or sat with him on the porch swing, or listened to him gripe about the smell of the dog or hold forth on a subject he knew nothing about, my eyes would fill and I would have to turn away. Getting him to Manhattan without a breakdown was an exercise in restraint and maturity—mine, not Sam’s. My mother had died suddenly a week before, and that loss, oddly, softened the blow. As Sam told his father, standing in his packed-up room at home, the last of his friends to leave town, “I’ve spent all summer saying goodbye, and I didn’t even know what that meant.”

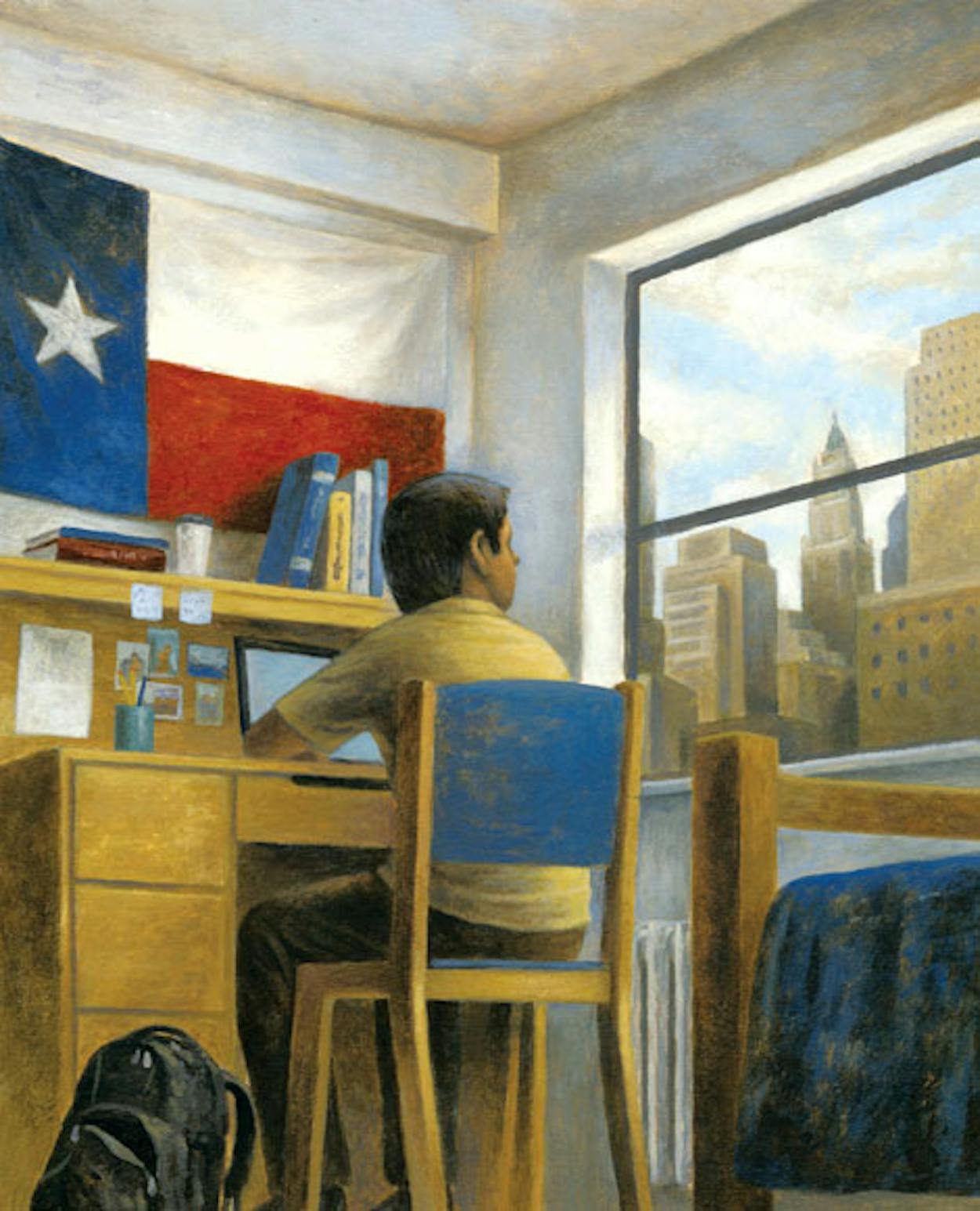

We made it to New York, met Sam’s roommate, discerned that he was not a serial killer, and checked out the million-dollar view of lower Manhattan from his fifteenth-floor dorm room. Sam pointed to the penthouse of an elegant high-rise. “That’s Beyoncé’s apartment,” he said, passing on the intelligence he had gleaned at orientation. The notion that someone else from Houston was nearby, even if she was a superstar who didn’t know we existed, gave me comfort. Later, Sam walked us to a community garden he’d found on the Lower East Side, lush with fall blooms. He was going to be a regular there, he said, “because I need to see the sky.” As time grew short, I began to panic. I gave him flyers I’d picked up off the sidewalk for Mexican restaurants that we both knew would do only in desperation. I ordered a Texas flag online for his room.

Finally, the morning came when we kissed Sam goodbye and watched him disappear into the crowd on Twelfth Street, walking with the same long-legged, splayfooted gait as my father. He didn’t look back, and my husband spent the whole flight to Houston staring out the window. Our job, essentially, was done.

What I didn’t see then but do see now is that my last-minute moves had more than one purpose. The bonds I was trying to cement for my son weren’t just to John and me but to Texas. If my mother were alive, she would appreciate the irony, because from the time I was six I was hell-bent on getting out of here. I demanded to spend summers with my aunt and uncle in Virginia, enduring their unair-conditioned house with the equanimity of a Zen master. In high school, my best friend and I used to talk endlessly about the lives we would live in “Green-Witch Village.” In Alamo Heights in the sixties, I was a dark-haired, dark-eyed klutz among the blue-eyed blondes who charted the changing seasons by shifting to different sporting events. I longed to live someplace where people read books and dressed in the latest fashions and argued about national politics. Someplace I might actually get a date.

But after college on the East Coast, I came back to Houston for a job as a paralegal. That was in 1976, and while I have lived briefly in other Texas cities and had my share of commuter relationships back east, Houston has been home since then, a great big city with the ease of the Texas I grew up in. Despite my earlier ambitions, I wasn’t constitutionally or emotionally suited for the East: I hated the cold and the reserve that went with it. From my parents I developed an appreciation of flamboyance but a distaste for pretension; I was impatient with closed doors, dues paying, pedigrees, and the past. In other words, they had raised a true daughter of Texas, one perfect for the booming Houston of the late seventies. As I grew older, fell in love, and got married (to a Virginia immigrant), I realized I was harboring an increasingly powerful, nonnegotiable conviction: I couldn’t possibly give birth to and raise a child anywhere else.

Once Sam was born, I set out to give him all that had been good in my Texas upbringing and none of the bad old backwardness, though anyone who tries to separate the two will find themselves tangled, as I did, in a host of contradictions. There were no baby books on “How to Raise a Texan”—at least that I know of—but we bought a house we could barely afford in a neighborhood north of downtown that seemed to me the closest thing to a small Texas town in the middle of a big city. Sam grew up not just with Fourth of July picnics, Halloween carnivals, and the Lights in the Heights at Christmas but with neighbors and teachers who loved him. He learned to speak Spanish and to love Mexico from the babysitter who, to get him to sleep, would rub an egg and a palm leaf in the sign of the cross on his back while murmuring the Lord’s Prayer—it kept the bad spirits away, she explained to my stricken mother-in-law. When Sam was old enough, he worked; his first job was at a local restaurant where the owner was a Kurdish immigrant and many of the waiters told very interesting stories about their lives before they were paroled. When Sam and his friends decided to cover a log cabin playhouse in the yard with graffiti, his outraged father made him repaint it. And, of course, as soon as Sam got his driver’s license—the morning he turned sixteen—he lit out, circling Loop 610 at speeds I hope to never know.

Somehow, all of this—independence, responsibility, a love of community large and small—added up to a Texas childhood, as much as the requisite rodeos, Alamo visits, and rides aboard the Brackenridge Eagle. When he left for college—where everyone asked him why he didn’t have an accent—Sam seemed to me a great advertisement for Texas males: funny and open-minded, optimistic but pragmatic, generous but shrewd. He also has a tough streak—“They need to get a job,” he hissed as we passed some Occupy Wall Street protesters in New York last winter. I do wish he had a little more affection for book learning—“I like knowing, not learning,” he explained during a talk with us about his grades. But no one can fault his loyalty. Even though he went to college out of state with our encouragement, he continues to make us promise never to sell our house. Three years gone and still a Texan. And I keep having those bursts of regional chauvinism: just a few days ago, I asked my husband what qualities he thought made Sam authentically Texan. John, who has been here for 33 years now, thought it over. “He’s hardheaded and he hates to ask for help,” he said.

“You can take all the pictures off my wall,” Sam told me a few months ago, when we were making home repairs. “That way you can use my room as a guest room.” Out of nostalgia and inertia, we had left Sam’s room as he had left it, so the walls were still covered with snapshots of his friends, some dating back to middle school. Underneath was a brilliant shade of turquoise I had let him pick out himself. He was now suggesting khaki. The only good news was Sam’s request that I send paint chips for his approval.

I take heart from his Facebook page, where, among all the pictures of vacations we have bankrolled and parties when he should have been studying, there are still plenty of shots of home. They include a car thermometer registering 106 last summer and photos of his old Houston friends chowing down on barbecue in front of a taxidermied javelina with cattle horns mounted on its head.

There are also a few shots from last October, when Sam brought his roommates down during fall break. Jack and Mike, who are from the same Connecticut town as Martha Stewart, had barely gotten off their late-night plane before Sam ordered them into his car and drove off to show them the lights of the refineries to the east, then bought them raspas at the stand near our house. Over the next few days we filled them up on Mexican food and barbecue. They couldn’t stop talking about how nice people were, and I thought I’d have to pick their jaws up off the floor when former governor Mark White stopped by our table during dinner in a busy restaurant and sat down for a chat. “That would never happen in Connecticut,” I wanted to say but didn’t. To paraphrase my lawyer friends, Texas speaks for itself. I did, however, hope that Sam got the message.

I don’t know why this matters so much. Sam has his own life and will do whatever he wants with less and less input from me. Maybe it is that my mother is gone, my father is 85, and my brothers and their children live far away, out of state. My mother’s brother, born and raised, like her, in San Antonio, is terminally ill. In other words, soon I will be the last one standing, and when I am gone, one family that has been here since the 1860’s will be gone from Texas. That’s a heavy burden to put on a child, so I just tell myself that even if Sam isn’t a Texan in Texas, he will always be one in his heart.

Recently, though, I couldn’t help myself, so I texted him. “Do you consider yourself a Texan?” I wrote. For good measure I added, “That’s not a joke.”

He answered back right away, the words I needed to hear: “Hahaha yes.”