While researching a history of Galveston in the late eighties, I came across an abstract sculpture in a small park on Seawall Boulevard. Its steel spirals were a representation of Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion of the world. The sculpture was perforated with small round holes that had to have been made by bullets. Someone had deliberately tried to destroy it. I knew the story of how Johnson had won the championship in 1908: He had battered the reigning titleholder—a cocky, loudmouthed, money-hungry Canadian named Tommy Burns—so savagely that the final moments of the newsreel footage of the fight were cut to protect the public from the spectacle of a white man getting knocked silly by a black man. White America never forgave Johnson for that victory. Standing by the statue, looking at those bullet holes, I realized that that hatred had endured.

I was reminded of that mindless vandalism last fall at the Texas Book Festival, in Austin, when I viewed a short film clip of Ken Burns’s documentary on Johnson that will be shown this month on PBS. The title, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, includes an ironic phrase coined by black writer W. E. B. DuBois, explaining white America’s attitude toward the black champion. What people failed to appreciate about Johnson, then and now, is that he was the fire-breathing embodiment of the American spirit. He refused to settle for being a second-class citizen. He was a “pure-blood American,” he insisted, whose forebears had arrived in this country long before there was a United States. Jack and his four siblings were the first generation of American blacks born after Emancipation. He grew up fighting in a street gang on east Broadway and quit school in his early teens to work as a stable hand and as a stevedore, picking up extra change fighting other black dockworkers in makeshift matches.

His first ring experience was in fighting exhibitions known as battles royal—in this version, a white man’s joke in which eight or more black fighters were thrown into a ring together, sometimes blindfolded, sometimes with their wrists or ankles tied together, sometimes naked. They were urged to maim one another until the last man was standing. Johnson left home for keeps when he was about 21, hopping freight trains and moving from city to city—Springfield, Denver, Chicago, St. Louis, Baltimore, Boston, fighting in small arenas for smaller purses, mostly against other blacks. He turned professional in 1895, the same year that the New York Sun warned readers that black athletes—boxers in particular—were a threat to white supremacy. No black man had ever been permitted to fight for the heavyweight title, whose holder has been described as the “Emperor of Masculinity.”

For two decades, as a contender and a champion, Johnson never once climbed into the ring against a white opponent except in front of an overwhelmingly hostile crowd. Newspapers referred to him as “De Big Coon” and “Texas Watermelon Pickaninny”; a reporter for the Baltimore American wrote that Johnson appeared as “happy and carefree as a plantation darky in watermelon time.” Contenders suggested that he was too black to have the heart of a fighter, which served as their excuse for refusing to fight him.

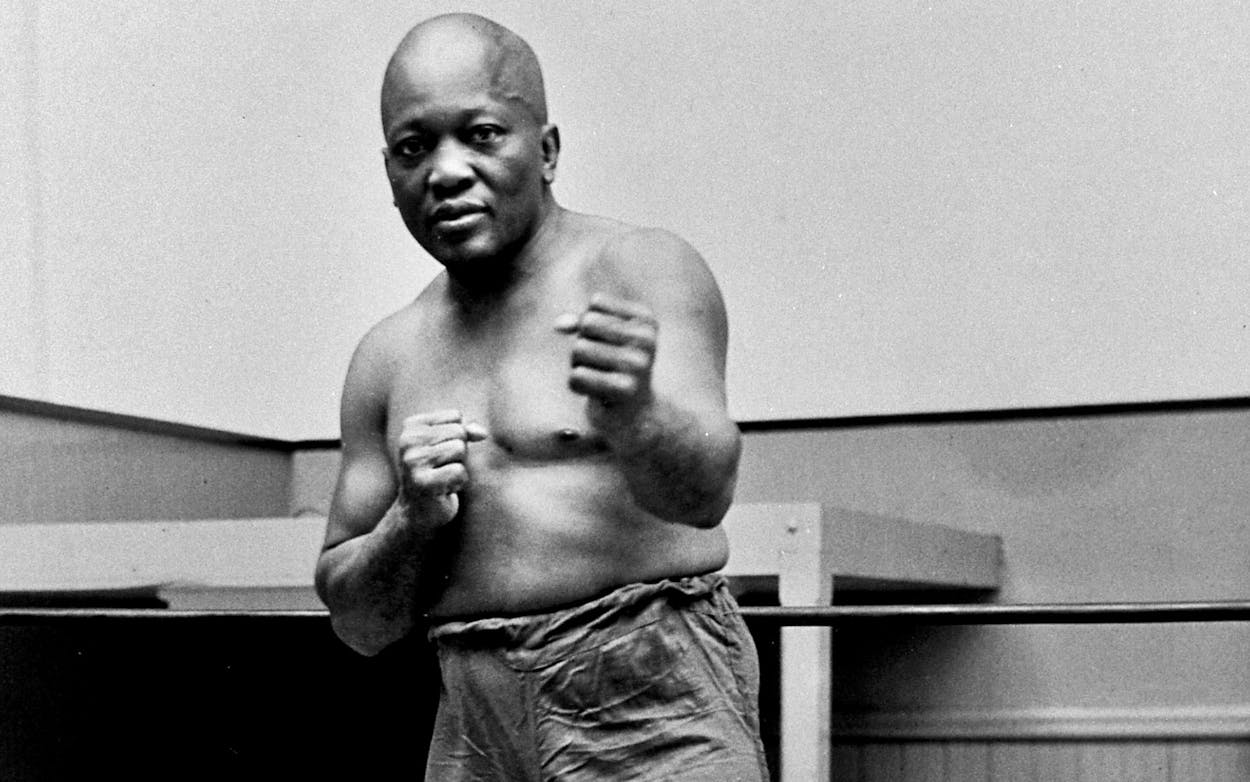

Johnson endured the slander with maddening calm, always grinning, always cool and in control. A boxer’s first task, it has been said, is to “turn his opponent into an assistant in his own ass-whipping,” and few did it as well as Jack Johnson. He may have been the best defensive fighter of all time, waiting for opponents to get close and then cutting them to pieces. Johnson’s easygoing manner lulled opponents into mistakes, and his sharp tongue destroyed their composure. “Poor little Tommy. Who ever told you you were a fighter?” he snickered as Burns chased him around the ring in Australia, challenging Johnson to “fight like a white man.” Though the memory of that fight has dimmed with the ages, the phrase that identified every subsequent challenger who took on and lost to the new champion is still with us—the Great White Hope, which was also the title of a Broadway play and a 1970 film based on Johnson’s life, both starring James Earl Jones.

Historian Geoffrey C. Ward, who researched and wrote the script for Burns’s four-hour documentary and later wrote a book with the same title, told me that Johnson’s career was characterized by three qualities: personal courage, masterful boxing, and a refusal to let anyone else do his thinking for him. “Jack Johnson was a very complex man,” Ward explained. “He read, he loved opera, he played the bass fiddle. Above all, he believed that a black man need not limit his horizons.” As his reputation (and bank account) grew, Johnson became a notorious bon vivant, partial to pricey call girls, fine wine, and games of chance. Always the fashion plate, he wore expensive suits; high, modish collars; diamond stickpins; and patent leather boots with spats and carried suede gloves and an ivory-handled cane. People were furious when he moved into a white neighborhood and struck temporarily aphonic when he announced that henceforth he would date only white women. He bedded them with wild abandon and even married three of them. His other passion was fancy racing cars, which he bought like candy. There were fewer than half a million cars in the United States in 1909, Ward told me, and Johnson owned five of them. Stopped for speeding in some Southern town, he supposedly tossed a roll of $100 bills to the sheriff, explaining that he would be driving even faster when he returned. The consummate showman, he loved making his ring entrance garbed in gaudy bathrobes and trunks; one outfit was described by a reporter as “screaming, caterwauling, belligerent pink.”

Americans had always accorded their heavyweight champion the right to drink, gamble, chase whores, and spend staggering amounts of money—“Gentleman” Jim Corbett and John L. Sullivan were hardly choirboys—but Johnson was judged by a different standard. When he dared buckle up the champion’s belt, the white world went crazy. An outraged media launched a desperate search for a Great White Hope to reclaim the title. Sullivan personally groomed a former wrestler named Kid Cutler, hoping he might wipe the smile off Johnson’s face. The champ put Cutler to sleep in the first round; then he looked across the ring at the crestfallen Sullivan and quipped, “How do you like that, Cap’n John?”

Writer Jack London, among others, begged former champ Jim Jeffries to come out of retirement and avenge the white man. Jeffries had sworn that he would never climb into the ring with a black man, but the lure of the biggest payday in ring history (over $100,000) caused a change of heart. Boxing experts were certain that Jeffries would regain the crown, but in the fifteenth round of what was scheduled to be a 45-rounder, the unimaginable happened: Jeffries sank to the canvas, one arm draped helplessly over the bottom rope, knocked off his feet for the first time in his career. A great silence fell across the crowd; it was as if the sun had set on the white race. Riots broke out across America. “On Canal Street, in New Orleans,” Ward writes, “a ten-year-old paperboy named Louis Armstrong was warned to run for his life.” Johnson had become the hero of blacks everywhere, both for what he had done in the ring and the bold way he lived his life. To Jeffries’s credit, the ex-champ later admitted to a reporter: “I could never have whipped Jack Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have reached him in a thousand years.”

By 1912 the relentless pressure was taking its toll on the aging Johnson. His wife, Etta, who had suffered for years from depression, killed herself. He married again, but by now the Justice Department was after him for twice violating the Mann Act, the so-called white slavery law that made transporting a woman across a state line for immoral purposes a crime. It didn’t matter that the law was applied retroactively or that, in one case, the woman had become his wife. Sentenced to a year in prison, Johnson, by his own account, bribed federal authorities to look the other way while he escaped to Europe.

He remained abroad for seven years, making numerous stage appearances, touring with vaudeville companies, and fighting exhibitions, dealing handily with all challengers. But in 1915, under a blazing hot sun in Havana, Johnson finally met a white hope he couldn’t beat, a Kansas giant named Jess Willard. By the twenty-sixth round, heat, age, exhaustion—and Willard’s paralyzing right hand—proved too much for the champ, and he crumpled to the canvas. A famous photograph of Johnson sprawled on his back, one arm apparently shading his eyes, helped spread a rumor that he had thrown the fight. Truth was, time had finally caught up with Jack Johnson, who had been fighting professionally for twenty years and was 37, far past his prime. By 1920 he was running a saloon in Tijuana, Mexico, and putting on strong-man shows and exhibition matches before small crowds in Mexican border towns. Eventually, he returned voluntarily to the States and served ten months in Leavenworth, finishing out his old sentence. He spent the next 25 years mostly in Chicago and New York, frequently working as a sparring partner with rising young boxers. In 1946, on his way back east from Texas, where he had performed with a traveling tent show, Johnson lost control of his high-powered Lincoln Zephyr in North Carolina and slammed into a telephone pole. At age 68, he died as he had lived—too fast and without permission.

Twenty-two years elapsed between Johnson’s loss to Willard and the emergence of another black heavyweight champion. Joe Louis was polite, nonthreatening, and, as they used to say, “a credit to his race.” Twenty-seven years later, another black champion, Cassius Clay—who soon changed his name to Muhammad Ali—got in the face of the white establishment, just as Johnson had. The difference was that he got away with it. Scholars of the sweet science have noted many similarities between Ali and Johnson: their speed and grace and the way they invited challengers to take their best shot. Neither champion felt obliged to step aside for any man, black or white.

Six decades after his death, Americans seem finally ready to admit that Jack Johnson’s only real crime was his “unforgivable blackness.” A group of U.S. senators, businesspeople, historians, and artists have petitioned George W. Bush to grant a posthumous pardon. I hope the president watches the documentary and understands the injustice done to this great athlete. For me, a presidential pardon would right not only the wrong done to Johnson but also the wrong done to his statue in Galveston years ago. Mark Muhich, the sculptor, tried to patch the bullet holes, but in the weeks and months that followed, the statue was regularly blasted by vandals using high-powered rifles and shotguns and defaced with Ku Klux Klan stickers and racial graffiti. When nothing remained of Muhich’s work except a mangled piece of scrap metal, the city carted it away.