On October 27, 1900, an Austrian-born mining engineer named Anthony F. Lucas spudded in an oil well on a hill near Beaumont. He’d drilled a previous well in the vicinity to a depth of 575 feet before running out of money and giving up, but this time he’d secured financing and brought in the Hamill brothers, a pair of expert drillers from Corsicana. Over the next few months the Hamills struggled through the oil sands without much success. By January 10, 1901, all they had to show for their efforts was a 1,139-foot-deep hole.

That morning, after breaking through some hard rock, they found their bit would no longer turn. They pulled it out and put on a sharper bit and were only partway back down the hole when mud began to bubble up and the well blew out. Six tons of four-inch drilling pipe shot out of the hole, terrifying the roughnecks, who ran for their lives. There was a brief pause in the action, followed by a massive eruption that blasted a black plume one hundred feet in the air. For the next week and a half, a giant pool of oil collected around the site as the geyser spewed uncontrollably and the Hamills worked to get a cap on it.

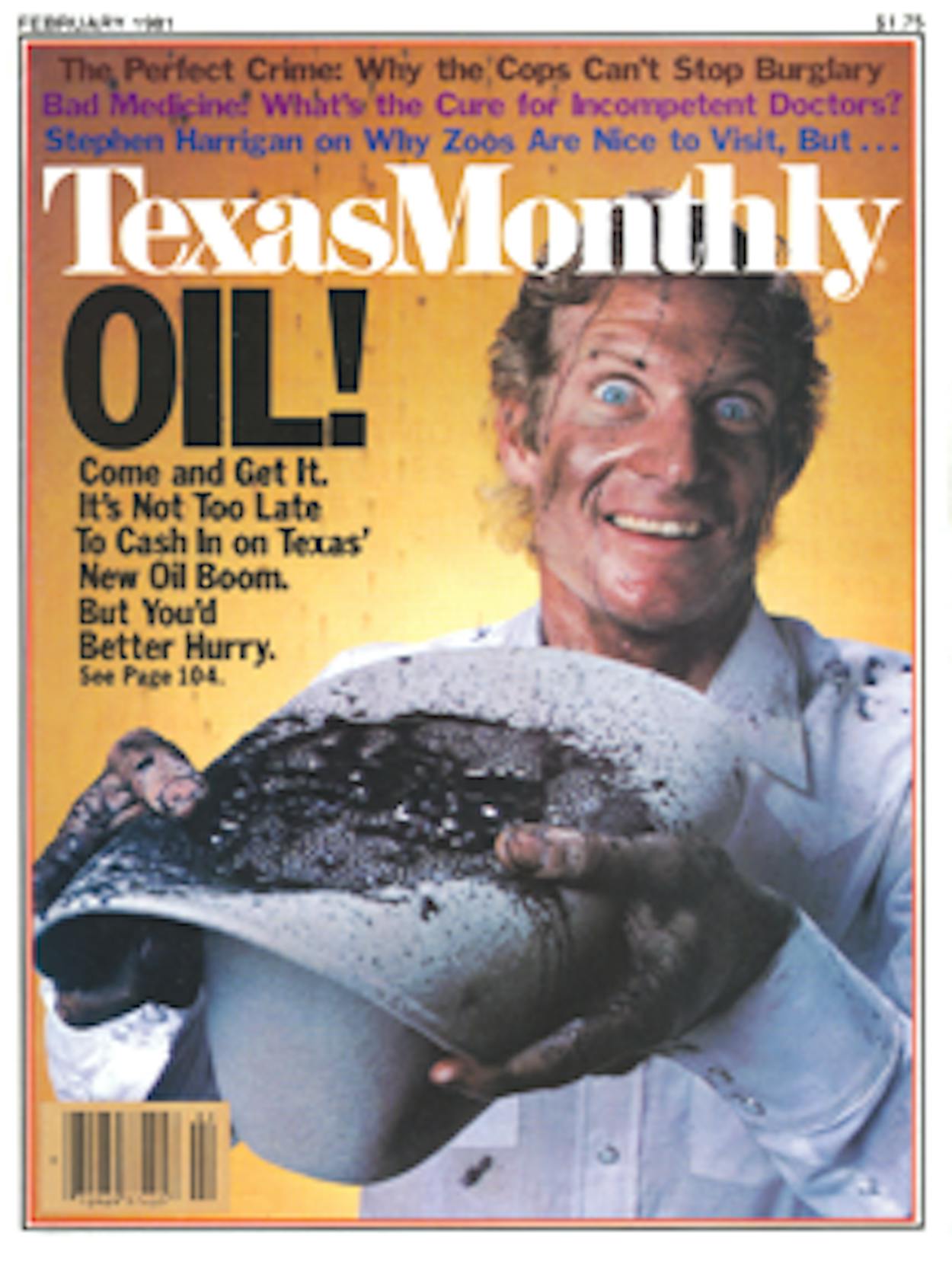

That classic image of Spindletop—a black column of liquid gold shooting up through a wooden derrick into a giant dark cloud—quickly became an indelible symbol of the thrilling new industry that would help define Texas in the twentieth century. “Easy oil” became part of the Texas myth (and it was a myth, since no oil is ever really easy; just ask the Hamill brothers). In 1981, when another full-fledged boom was under way in the Austin Chalk formation, we put a wildcatter on the cover with his hat full of oil. “Come and get it” read the cover line. But even then the business had changed radically. “There is no easy oil left in Texas,” we wrote at the time. “Oil is still in the ground, all right, but it is harder to find and still harder to recover.”

Fast-forward to 2010 and it’s even harder. This month, Skip Hollandsworth reports on a new oil boom under way in Midland, where there were supposed to be no more booms. It seems a clever drilling technique has unlocked the Permian Basin’s hidden reserves, made some people very rich, and started a familiar stampede of landsmen to the county courthouses of West Texas. Like the Giddings boom that we wrote about in 1981, the new boom in Midland is the result of a handful of independent operators taking a chance on an unorthodox theory. Skip’s story (“That’s Oil, Folks!” page 114) reminds us of the romance and excitement—and tremendous risk—of the search for oil, but it also makes it clear how much the business has changed since Spindletop. This new play in the Permian Basin may yield 1 billion to 2 billion barrels of unexpected oil. That’s great for Midland and Odessa, but it’s not going to change the world, which now requires 86 million barrels of oil per day to function.

Ironically, this new boom began on leases that British Petroleum abandoned in the mid-nineties as it was pulling out of the Permian Basin to head for the Gulf of Mexico. We all know how that turned out. If the Lucas gusher was the classic image of the oil business in the twentieth century, the indelible image that may define it in the twenty-first century is of another gusher: a grainy video of oil billowing out of BP’s Deepwater Horizon well on the ocean floor. For 86 days this past spring and summer, that video was omnipresent on cable news, putting into stark relief the dangers of offshore drilling and the urgent imperative we have to develop an alternative to fossil fuels. Without one, we’ll need every last drop of the 40 billion barrels under the Gulf, however hazardous they are to retrieve.

But Skip’s story is not about energy policy or the politics of offshore drilling. It’s about how a particular corner of the oil business really works. And that’s why you should read it. Especially now, when the phrase “oil business” tends to conjure images of exploding rigs and shamefaced executives. The men Skip writes about have more in common with Anthony F. Lucas and the Hamill brothers than they do with deposed BP CEO Tony Hayward. They aren’t villains or saints. Just real people making tough decisions on the hunt for something precious, finite, and mysterious.

NEXT MONTH

Friday Night Lights and the history of TV Texans, how to balance the state budget, what the oil spill did to Houston, the best little ballpark in Texas, an unforgettable story about the death penalty, and yet another show-down at the Alamo.