Certain people have all the luck. Somehow, through family, talent, or blind fortune they manage to land themselves in jobs with extravagant pay, free (or at least tax-deductible) trips to exotic places, not too much responsibility, certainly no actual labor, the adulation of thousands, and the envy of us all. “Philanthropist” is a job like that, as are “sportsman,” “rock star,” and “ex-president.” The rest of us have to work, damn it. Really work. In all of the Department of Labor’s 1371-page Dictionary of Occupational Titles, the only job that even sounded cushy was “banana ripening-room supervisor.” There may be more to this job than one would suspect, but I imagine the supervisor coming in about 11 a.m., looking around, saying, “Well, sir, these bananas seem a little riper than they were yesterday,” and then breaking for lunch.

Still, no matter how hard or easy it is to watch bananas ripen, it’s obvious that some people work harder than others. You, for instance, work harder than your boss. In fact, you may think your job is the hardest there is. But that’s where you’re wrong. The six Texans on the following pages have to worry about getting run over, burned, nauseated, blood-splattered, bored, or blown up. After reading about them, your troubles won’t seem quite so bad.

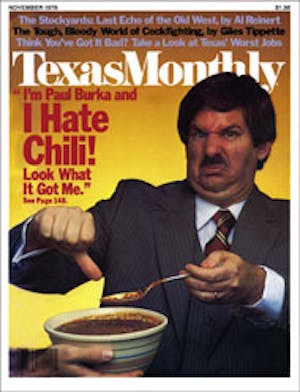

BLAST FURNACE TENDER

The place where Charles Proctor has worked for the last 31 years looks like the entrance to Hell and is just as hot. For all his adult life he has worked around the 22-foot-high blast furnace at the Armco Steel plant near the Houston Ship Channel. Twice a day Charles supervises the “cast” of the furnace, the releasing of 2800-degree flowing molten iron (about 320 tons and hour) down a sand-covered trough and into a 200-ton-capacity ladle that waits below the furnace floor on a rail track. Charles wears special clothes for his job: a full-length woolen “spark coat” to protect his body from sparks and flame, heavy gloves, protective glasses, a face shield, and shoes with metatarsal guards. The temperature around the trough stays near 140 degrees. Showers of sparks, smoke, and flames and a continuous mist of graphite and ashes fill the air when the glowing, orange-red, lavalike flow of iron begins. He also watches a separate slag flow that goes down another trough to the slag pit. “It looks a lot worse than it is,” says Charles, “but it’s still dangerous, no doubt about that. I’ve been burned some, but that’s part of the job in making iron. And I make good money.” Yes, he does—$77 a day, plus benefits, for tending Armco’s blast furnace.

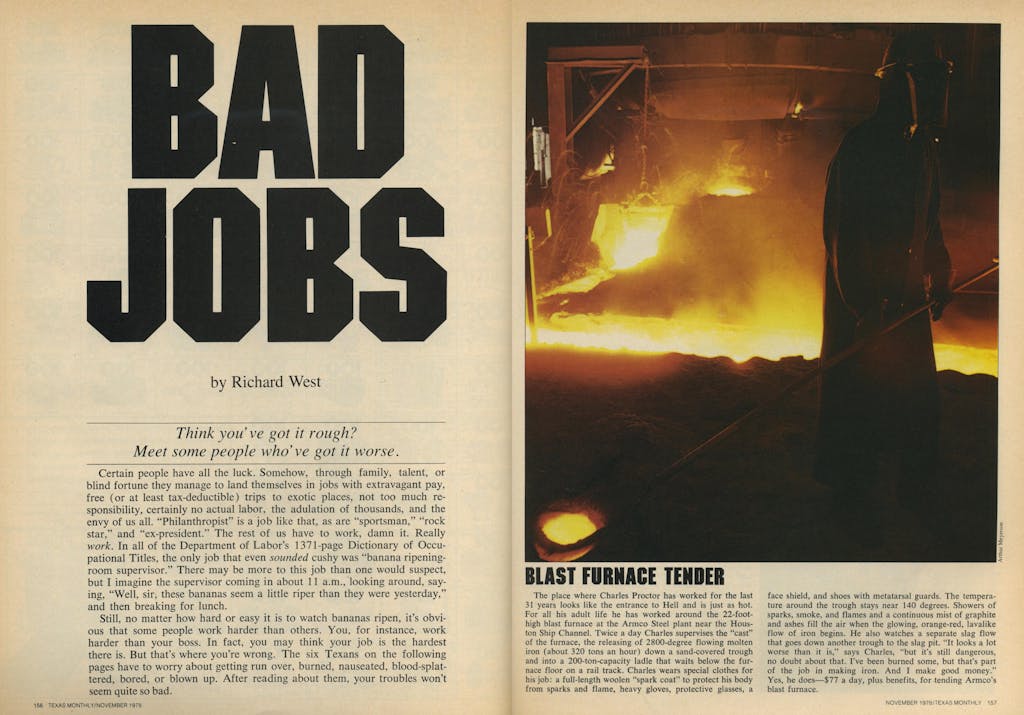

HIGHWAY BUTTON LAYER

Highway button layers must assume one of the worst of vocational postures, a stance formerly associated with cotton pickers and now chiefly the lot of vegetable harvesters. They must bend the torso into a walking question mark and maintain that position for hours at a slow stroll. After several hours, the pain shoots up the legs and hits the lower back. The fingers and wrists begin to throb after pushing down the first several hundred of a day’s quota of ceramic or reflective traffic buttons, which can be as many as 7000 during the long hours of summer. On a 90-degree day, the temperature of asphalt reaches 120 degrees. Less than four feet away, huge semis whiz by the button layers, spraying gravel over such human question marks as Robert Sims. Sandblasters often add to the workers’ misery, forcing Sims and his crew to don masks to avoid choking clouds of dust. During the ten- to twelve-hour day, there is no scheduled coffee break and only thirty minutes for lunch. “Yeah, all that’s true, plus you never get the epoxy off yourself or your clothes,” says Robert. “But I enjoy the travel—we work Texas and surrounding states—and I like the people I work with. I’m taking home about $4.50 an hour, and for right now button laying is what I want to do.”

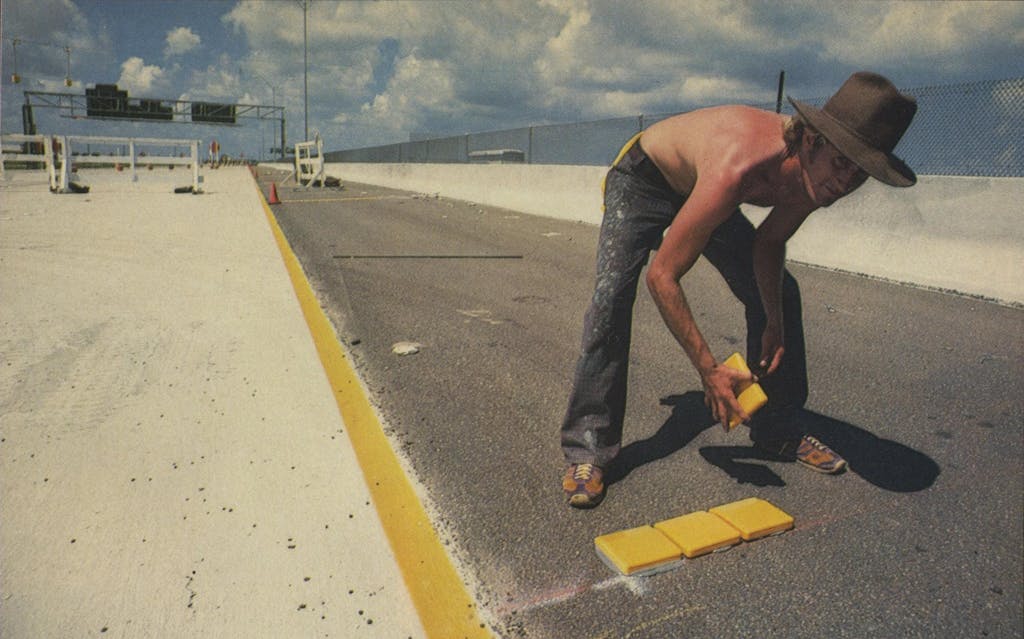

RENDERING PLANT WORKER

He drives a truck with a signboard that reads YOUR USED COW DEALER OF TEXAS. Used indeed. The animals—cows, horses, pigs, sheep, dogs, and cats—Lucas Longoria picks up off the road and hauls from the fields, using his gloved hands, a winch, and some cable, are dead. And they usually have been for some time. They are smelly and putrescent. And what is a good deal more disconcerting, they tend to fall apart when the winch cable is attached to an extremity. Lucas works for Spearman By-Products, a rendering plant in the Panhandle town of Spearman. Once delivered, the dead animals are skinned, sliced, divvied up, and sent to their next destinations for processing. Skins and meat go to Amarillo to be made into pet food and chamois, hooves to Chicago, and so on. “I’m trying to get used to it,” says Longoria with a weak smile. “I spent the first two months getting sick to my stomach, but now it’s better. It’s my job.” After six months of cruising the roads and byways of the Panhandle Plains, Lucas has, well, sort of adjusted to his daily dealings. He lives with his brother in a mobile home next door to the plant, upwind. While he may not have the gleam of enthusiasm in his eye when talking to people about his vocation, he has developed an admirable tolerance for a job that most of us wouldn’t approach with a flagpole.

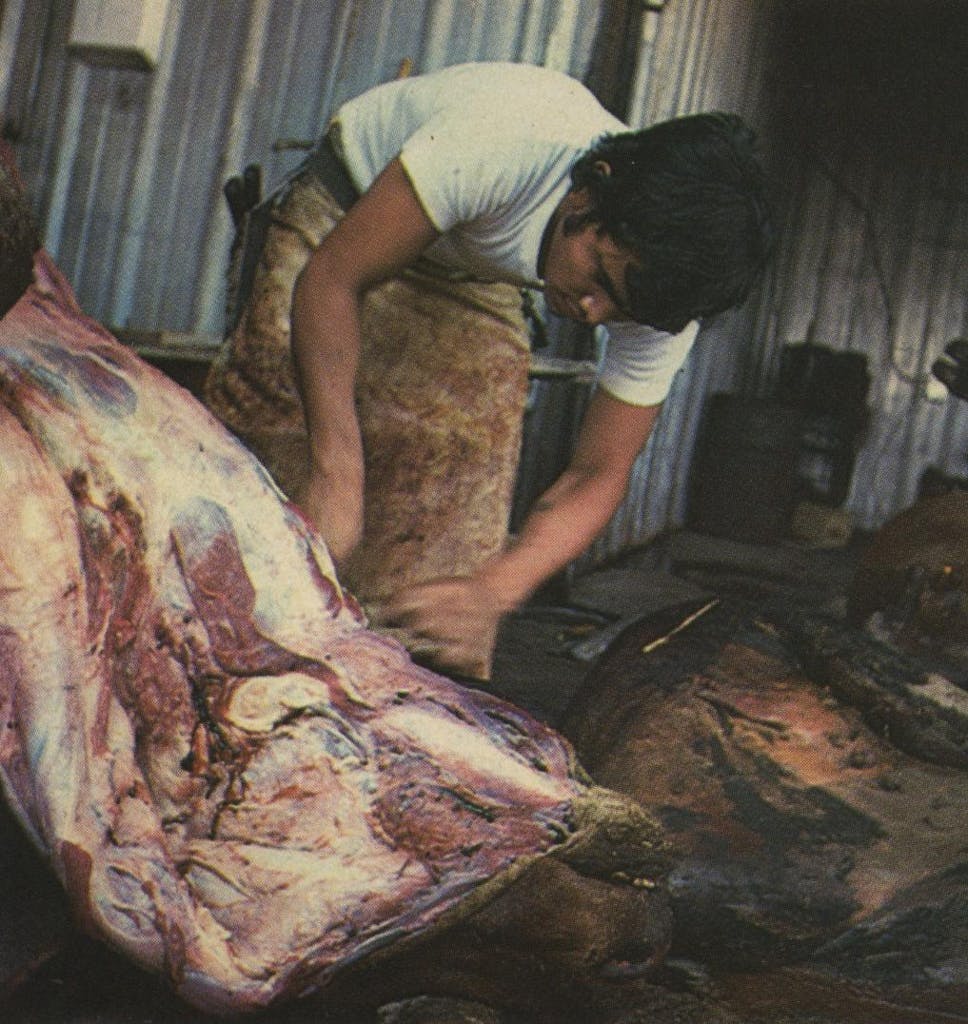

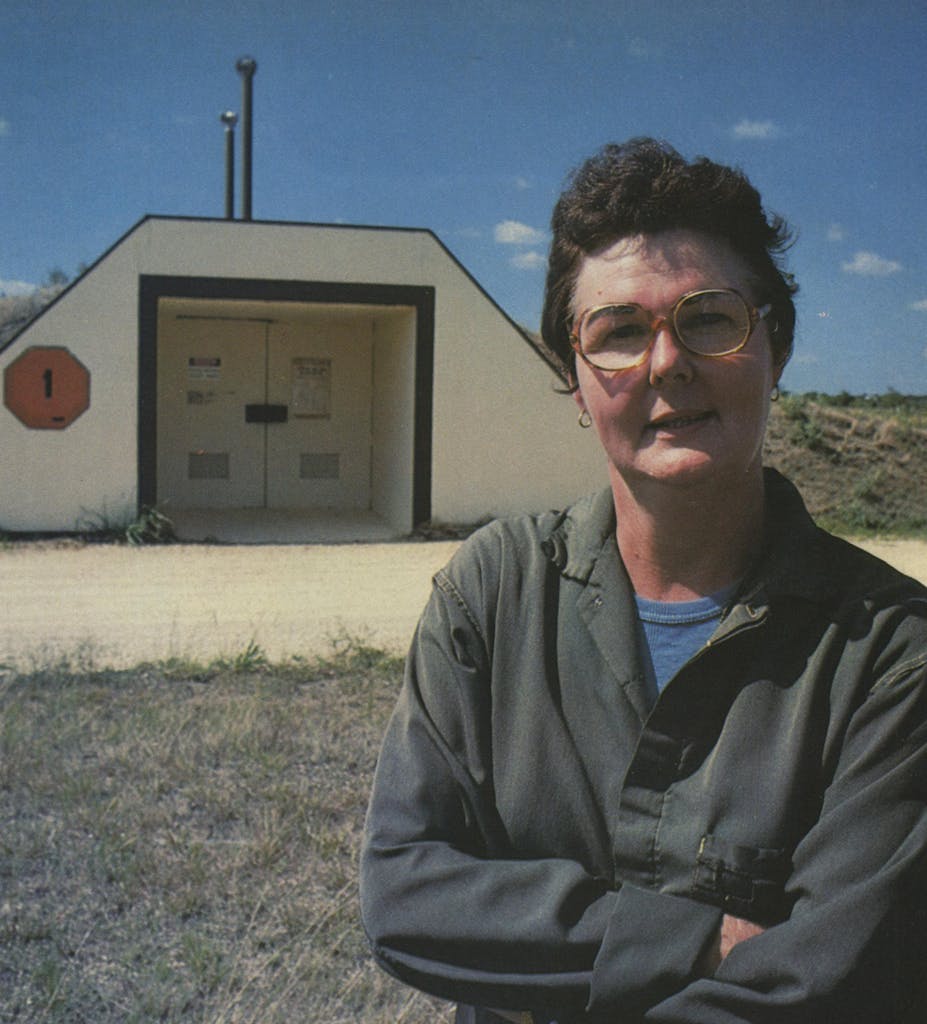

MUNITIONS PLANT WORKER

Most of us face the threat of death only when driving on freeways. Faye Preissinger lives with the threat of death every minute of her eight-hour working day. She loads detonators and ignition cartridges with explosives at the Goex, Inc. munitions plant north of Cleburne, where four employees were killed by explosives in April and another seriously injured in July. The great danger at Goex is static electricity. When thunderstorms approach, all buildings are evacuated. To keep her own static electricity away from the powders, Faye wears special all-cotton, highly flame-resistant coveralls that have stainless-steel wires woven into them; special operating-room shoes; and a wrist sweatband with a grounding wire attached to the floor. She works behind a waist-to-forehead Plexiglas shield. With a tiny dipper, Faye spoons one grain (there are 7000 in a pound) of lead azide and three and a half grains of HNS, a high-temperature explosive, into a detonator cavity. Working steadily, she can turn out about a hundred detonators a day. Faye also supervises a roomful of air-operated loading machines, run by three other people, which fill ignition cartridges for foreign mortar shells with forty grains of M9, a nitroglycerine propellant that looks like shotgun powder and has a very low flash point. “I just don’t think about it,” she says. “If the day seems wrong or I don’t feel right, I go home. I won’t talk about explosions. If I talk about it, I think about it and I can’t do my job.”

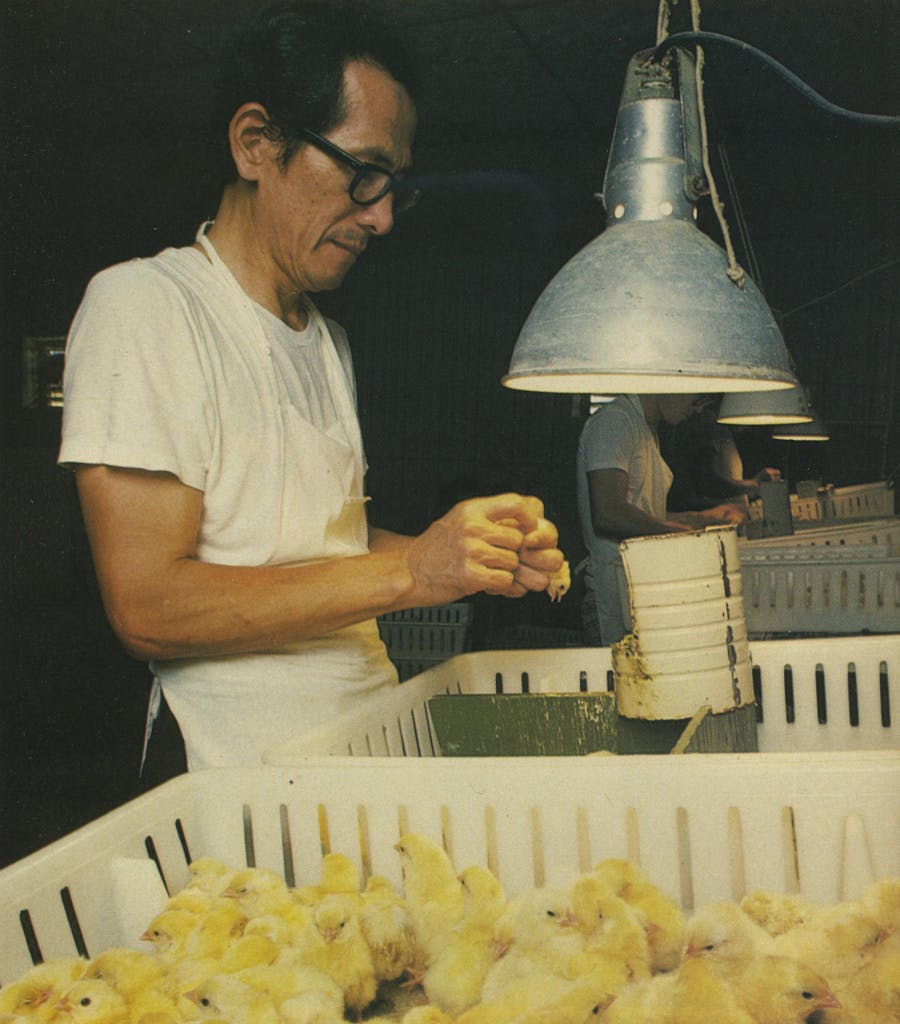

CHICKEN SEXER

It’s a risky assumption, of course, but we trust that even the most urbane boulevardier knows that chickens hatch in two denominations: male and female. But which is which? As far as we know, neither modern science nor Neiman-Marcus has yet unveiled a machine that can make this crucial distinction. That’s why there is the chick sexer, a job title that if listed in the classified ads would draw enough applicants to fill the Astrodome and Big Bend. Little do they know. Depending on the variety of chick, Sat Satio, a sexer for 21 years, can determine gender by measuring feather length or by what is euphemistically called the “vent” method—a finger examination of the anus of a one-day-old chick. In the vent method, first aim the yellow cheeper’s vent toward a tin can and squeeze it to relieve the examinee of excrement. After the passage is clear, examine the anus with a digit for a bump. The bump-bearing male chicks are tossed, alive and cheeping, into plastic garbage bags destined for the county dump. Females are saved to lay eggs. “I went to chick-sexing school in California before coming to Bryan in 1958,” says Sat, who was born in Japan. “No, I don’t mind it. Sometimes it’s messy but it’s my profession. It is a hard job to learn. I’m sorry we have to throw away the males. It’s not nice, but no one can use them.” Satio prefers the feather method to the vent method.

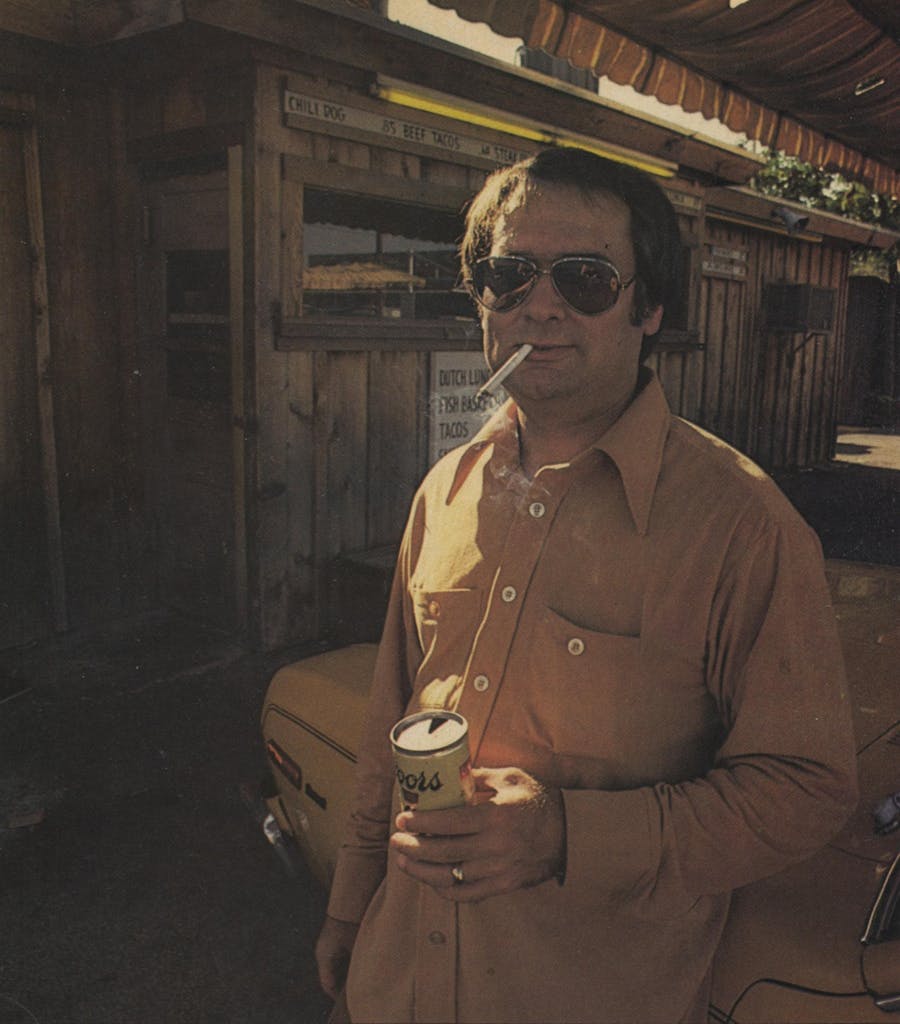

FULL-TIME RESIDENT OF WICHITA FALLS

Don’t apply. It’s hard work living in Wichita Falls. Most people would rather be charged by rhinos. Wichita Falls surpasses even Waco as the pits. At least Waco has the Brazos River, the Texas Ranger Museum, and the Lone Star Tavern. Wichita Falls is next to nowhere and all it has is bad weather. Last summer people in Dallas wilted for 36 days under 100-degree-plus weather, but Wichita Falls had them beat by an average of 3 degrees and 17 days. It’s no better in winter—unbearably cold, and it snows. It also blows. The 1978 Guinness Book of World Records lists Wichita Falls as the spot where the highest tornado winds on record occurredo280 miles per hour on April 2, 1958. Barry Williamson, like Wichita Falls’ other 95,007 inhabitants, should get hardship pay. He’s lived there for almost all of his 32 years. “I escaped twice,” says Barry, “only to come back, like most of my friends. We must be crazy. The countryside is drab brown with sickly mesquites, the weather is unbelievable. I’ve tried to kick the habit, but it’s no good. Our city’s motto is “The City That Faith Built.” I have always assumed that it referred to some dark, masochistic tendency in human nature, and that appeals to me, like watching Howard Cosell. If a city could be a person, I guess Wichita Falls would be Howard Cosell, the city you love to hate.”

- More About:

- Business

- Wichita Falls