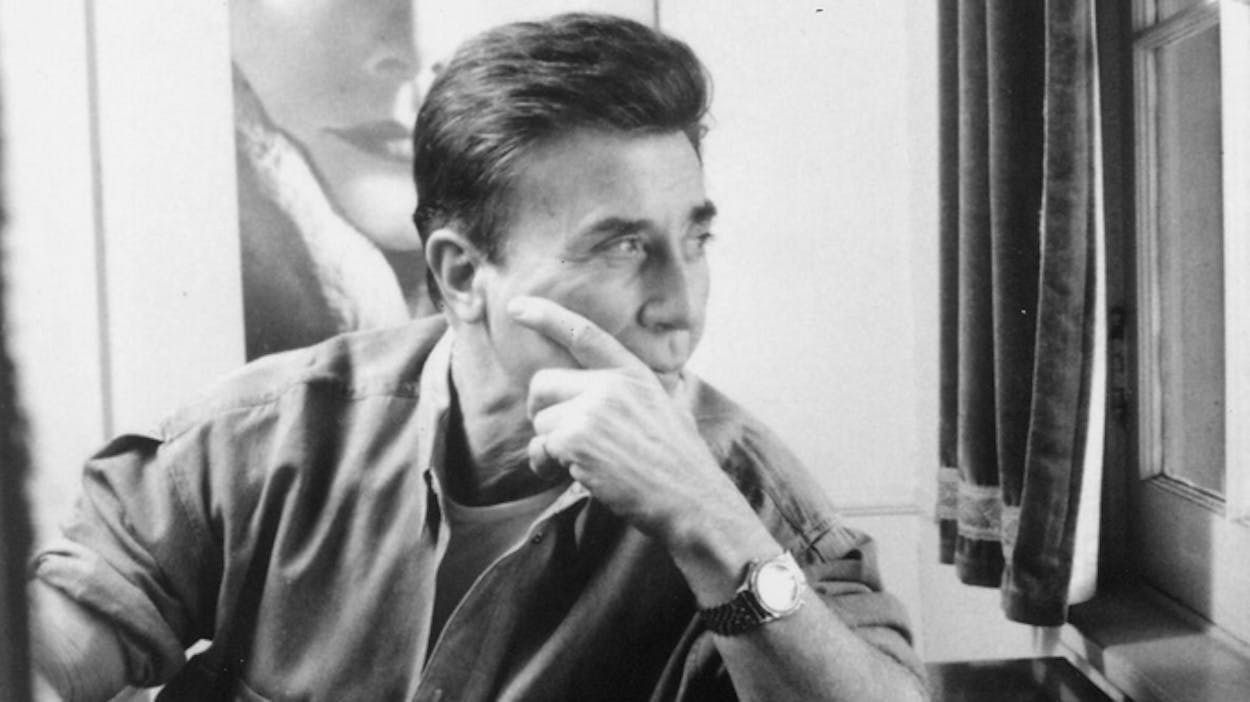

Writer John Rechy, named Juan Francisco Flores Rechy, was the youngest of five children born to Mexican parents in El Paso during the Depression. Of that time, he once wrote, “There was so much poverty and hunger in El Paso and Juárez that we didn’t consider ourselves poor, because we ate and had a home.”

He did, however, feel like an outsider on another count: his homosexuality. Though years away from exploring his orientation, Rechy felt isolated because of it. He was an outsider who would, as an adult, be deemed a sexual outlaw.

Nevertheless Rechy always enjoyed attention and found the arts a means of attracting it. When he was seven, he sent Shirley Temple, the child actress, a letter asking to co-star in a movie with her. He also wrote a series of stories, all of which he titled “Long Ago.”

Twenty years later, his coming-out rite of passage resulted in his first novel, City of Night, which turns fifty this year. The now classic book chronicles the journey of a young Mexican-American from the border town of El Paso into the gay underworld of the fifties. As the book jacket boldly announced, “This is a novel about America.”

The novel’s mesmerizing opening sentence perhaps sums its themes up best: “Later I would think of America as one vast City of Night, stretching gaudily from Times Square to Hollywood Boulevard—jukebox-winking, rock-n-roll-moaning: America at night fusing its dark cities into the unmistakable shape of loneliness.”

In a telephone interview from Los Angeles, where he now lives, Rechy, 82, said he had written City of Night on a rented typewriter in the family’s modest home in the projects. He recalled how his brother Robert and his mother, Guadalupe, formed an assembly line around the kitchen table to send his first novel off to his publisher, Grove Press, in New York.

“It was a great, great night,” Rechy said. “I had to make four carbon copies, and they all had to be separated. So each of us was going around with a stack of papers, laying them out. When my family saw the number of manuscript pages, they must have realized this book was for real.”

His writing as a teenager led to a scholarship at Texas Western College where he majored in English and minored in French. He edited the school newspaper and was later fired for trying to make it “too literary. He enlisted in the Army after receiving his bachelor’s degree and served in the 101st Airborne Infantry Division overseas.

After his military duty, Rechy applied to be in Nobel Laureate Pearl S. Buck’s graduate creative writing class at Columbia University with his story “Pablo!” Buck did not admit him. “Instead of going to Columbia University, I went to Times Square,” where he found himself hustling on 42nd Street, Rechy said in an earlier interview. A year later the New School for Social Research writing program accepted him. It also led to his writing on social issues for the Nation and the Texas Observer.

City of Night began as an unsent letter to a friend but ultimately appeared as short fiction in Evergreen Review, Big Table, Nugget and The London Magazine. After Rechy secured a contract to write the book, he would return off and on to El Paso to work on the novel until its completion.

Rechy said he panicked when the galley proofs arrived.

“There was a big problem,” he said. “In print, it was all ‘different’— wrong.” He began the task of rewriting and making adjustments. “The book was virtually rewritten on the margins and on pasted typewritten inserts.” He offered to use his royalties to pay for the corrections, but Barney Rosset, the Grove Press publisher, agreed to the changes.

Once the book was published, no one was more surprised by its success than its author.

“I thought it would be critically successful but not successful in the commercial publishing world,” he said. “How wrong I was!”

The book sold 65,000 copies in hardcover and remained on the New York Times best-seller list for 25 weeks, peaking at number three and vying with the works of James Michener and J.D. Salinger one month, and those of Ian Fleming and Pearl S. Buck the next. (Rechy never sent Buck a copy of the book. “I later was asked to teach the same class at Columbia,” he said.)

Despite the novel’s astonishing sales, the year after it was published proved difficult. “I was still living in the El Paso projects,” Rechy said. “My brother got me an old Studebaker, and I began to travel again. I didn’t want to do any kind of publicity. It scared me; it really did. Reviews like the one in The New York Review of Books were devastating.” Rechy’s low profile, however, led some to question whether he actually existed. A number of imposters sprung up around the country claiming to be him.

“I was immediately categorized,” Rechy later told The Los Angeles Times. “I wasn’t just a homosexual writer. Some critics insisted I was a hustler who wrote books. To them, I was never a writer who just happened to write about hustling.”

The critical tide however soon changed, and writers like Gore Vidal, James Baldwin, Larry McMurtry, and Frank O’Hara praised City of Night for its new and authentic voice.

Nevertheless, Rechy’s groundbreaking work did not sit well in the conservative, mostly Roman Catholic Latino community back in Texas.

“For years, people didn’t consider me a Mexican-American,” Rechy said. “A couple of Chicano writers got annoyed and angry for me claiming to be Mexican-American. It’s been more difficult for me to come out as a Mexican-American than come out as gay.”

For the gay Chicano writer Benjamin Alire Sáenz, winner of this year’s PEN/Faulkner Award and a teacher in the creative writing department at the University of Texas at El Paso, Rechy’s novel is “without a doubt one of the finest literary works ever written.”

“It saddens me to think that it is rarely taught and mentioned in the Latino literary canon, which only goes to show how homophobic the literary establishment has been,” Sáenz said. ”What he taught me is this: to banish all fear when I sit down to write.”

Writer Dagoberto Gilb, a former winner of the PEN/Hemingway Award, included Rechy in his Hecho en Tejas!—A 2007 anthology of Texas Latino writers. “When I began reading, it was never for any school class.” Gilb said in an email. “Rechy was from my skewed and screwed up home and homeland. He didn’t take the predictable roads for browns or whites, got no easy goody-goody points going in. I knew LA streets, his El Paso, hustling and scamming, and getting away. I knew what he was doing and how it played, the night games, the wild body life he was in. And it was in writing, in a story!”

Half a century later, Rechy is justly proud that his book has been translated into many languages (including Czech, Chinese, and French), has sold millions of copies, and has never been out of print. His body of work ranks as a major achievement in American, Latino, and gay literature. Just as important has been his influence on artists, filmmakers, writers, and musicians from David Hockney, Gus Van Sant, James Franco, Michael Cunningham to Tom Waits, the Doors, and David Bowie.

He taught creative writing classes at the University of Southern California for many years and, until recently, a master writing class for published writers. His 2008 memoir, About My Life and the Kept Woman earned him his best reviews in years. Edmund White called Rechy “one of the most heroic figures in contemporary American life . . . a touchstone of moral integrity and artistic innovation.”

Despite writing a dozen other well-reviewed novels and nonfiction, including two national best-sellers (Numbers and The Sexual Outlaw), Rechy has never managed to completely escape the shadow of his first success.

“I have a competition going with City of Night,” Rechy said. “Today, it is better known than I am. And I might add that book is more loved than I am. People will come up and say, ‘I loved your book.’ And I say, ‘Which one?’ I think of Don Quixote, who is more famous than his creator, Cervantes.”

When asked what he treasures most from the writing of City of Night, Rechy recalled his mother’s influence and encouragement in making his groundbreaking novel a success. “I translated parts of the novel into Spanish for my mother, who only spoke Spanish, and she would say, ‘You’re writing a beautiful book, m’ijo.’ When the book was published and there were best-seller lists or new translations, then she would say, with enormous pride, ‘Ay, esa Ciudad de Noche, m’ijo.’” Oh, that City of Night, my son.

Those words became his mantra throughout his literary life.