Blackie Sherrod inspected the three or four manicured acres surrounding A. C. Greene’s semi-mansion in a much-advantaged section of Dallas, cocked his head to monitor the sweet calls of summer-morning birds, and sat down at an outdoor table loaded as if to accommodate a threshing crew: platters of eggs, bacon, cantaloupe slices, exotic breads, jams and jellies, coffee, pitchers of fruit juice, and maybe assorted samples of caviar or candied yak’s ass. He took in the grandly bent weeping willows, the sun-dappled swimming pool and bathhouse, the tall hedges hiding the green grounds from the gazes of Democrats or other riffraff. Sipping a spiced bloody mary, he said, “Boy hidy, A. C., all this sure is . . .”

Sherrod hesitated, as if determined to choose the exact right word—it is, after all, the way he makes his living—and you could see ol’ A. C. Greene, a Depression-era Abilene boy who was not born fast friends with money, puffing with the pride of ownership and preparing to respond to some record-breaking gracious compliment.

“. . . totally,” Blackie said, “and completely . . .”

Out of this world, he might say. Or beyond belief. Somesuch. A. C. nodded and beamed like a politician being bragged on, patting a well-shod foot as if impatient to deliver his own pretty little acceptance speech.

“ . . . vulgar,” Blackie Sherrod finished.

Before the manor’s lord could blink good, Sherrod smote him again: “What’d you plant the most of this year, A. C.? What time you commence whupping-up on them slaves?” A. C. Greene, knowing when he’d been out-country-boyed, threw up his hands and laughed a crippled giggle.

Betty Greene thought to ask of Sherrod’s wife: ‘How’s Marilyn?”

“Expensive,” Blackie said.

Sherrod is rarely without a swift riposte. When young Tom Johnson (who’d been LBJ’s right hand, yes, but hadn’t excessive experience newspapering) came aboard as editorial top dog for the Dallas Times Herald, he said to Blackie Sherrod, “How do you get a good job like sports editor?”

“Oh, I guess like you get to be editor-in-chief. You start at the bottom and work up,” Blackie shot back at his new boss.

William Forrest (Blackie) Sherrod has been named the Outstanding Sportswriter of Texas ten times in fourteen years and probably would have won them all except for picky laws against monopolies and unfair restraints of trade. The National Headliner Award is his for being found the most consistently outstanding sports columnist in the whole blamed United States. Felix R. McKnight, recently retired vice-chairman of the Times Herald—where Sherrod has captained the sports section since 1958—claims his man has won more awards than any writer in Texas newspaper history.

McKnight assigned Sherrod to cover the Apollo 11 space shot, “as a change-of-pace observer of the fringe drama attending a moonflight.” All Blackie did was win the Texas Headliner Club’s award for science writing, though I personally know he fails to understand the theory of the wheelbarrow or what makes a screwdriver work or why bees suck flowers. When McKnight dispatched him to the 1960 Democratic National Convention as a sidelight writer, Sherrod’s yarns were picked up by the national wire services; bags of fan mail and job offers poured in. In the shocked chaos following the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas, it was Sherrod they plucked from the fun-and-games section and placed in charge as rewrite coordinator on the news desk. Again prizes were won. Sherrod’s personal account of the death of young Freddy Steinmark, the Texas Longhorn football player who lost a leg and then his life to cancer, won a Pulitzer nomination. He is the author of three books (one on Darrell Royal, one on Steinmark, and a recently published collection called Scattershooting) and he has more professional admirers than the Happy Hooker.

Perhaps a writer’s work may best be judged by how many of his colleagues steal from him. A columnist on the Texas Gulf Coast so persistently thieved from Sherrod’s column that Times Herald authorities ultimately complained and the would-be genius was fired. In 1950, when Sherrod was a columnist for the Fort Worth Press and I was the rookie one-man sports department for the Midland Reporter-Telegram, it was my urgent habit to be on hand at the Scharbauer Hotel each day to buy all six copies of the Press left at the local newsstand. Five were pitched into the handiest trash can. This wasteful practice guarded against my bosses and readers learning where I got those many little funnies shamelessly sprinkled throughout a daily column carrying my own by-line. Had the Midland paper observed a policy of granting raises, I’m confident Blackie would have earned me one.

Not that the whole world was fooled. No, for when I moved on to the Odessa American, a resident sports scribe named Ben Peeler wigwagged me into a neutral corner to whisper that our newspaper wasn’t big enough for both of us to crib from Blackie Sherrod, and, by gum, he claimed certain inalienable seniority rights. Within the last fortnight I enjoyed a magazine piece by a freelance writer who’d stolen enough lines from a single Sherrod column to retire on. All that doesn’t bother Blackie much more than the running colic, “seeing as how I’ve robbed ole Shakespeare and S. J. Perelman purty good myself.”

One flies in the face of many honors and an old personal hero in faulting Sherrod. It might be done, however, on the grounds that he sometimes seems a bit much the “house man” in covering sports. He may be so enamoured of games and the men connected with them that he forfeits certain critical observations. The same thing can happen to political reporters who become more like the cops than the gumshoes they cover. It is an occupational hazard.

One is discomforted, for example, in hearing Blackie Sherrod explain why he never has concentrated on covering labor or economic issues in sports. “That bullshit is so hard for the average man to understand, it leaves him cold. Hell, it leaves me cold. We try to keep it simple and bright, to cover the personalities and the team, and I don’t think the Kansas City milkman cares about anything else much. So we don’t dwell on the Reserve Clause or the Rozelle Rule. If you can keep sports simple enough that women can understand it, then you’re gonna get your readers.” The response seems simplistic, naïve, male-chauvinist-piggish, and perhaps a little self-serving.

Has a writer, with access to inside information and the expertise to make sense of it, no duty to educate the reader? The Reserve Clause and the Rozelle Rule exist as vital realities; they influence the teams, the games, and the standings, to say nothing of the individual lives of ball players. Could not the Arlington waitress of the Oak Cliff barber, capable of understanding Blackie’s explanations of post patterns or cornerback duties, be made to realize the hardships of families whose athlete breadwinners may be sold or traded to distant cities on a moment’s notice? Would not the Kress employee quickly understand that she could not handily go to work for Woolworth’s if governed by a rule requiring her to play out a year’s “option” before becoming something called a “free agent?”

Sherrod says he didn’t write of Gary Shaw’s Meat on the Hoof—a super-critical look at Darrell Royal’s football factory—“because Shaw never came to see me.” Well, did Dick Nixon go see Woodward and Bernstein about Watergate? Did Faulkner or Hemingway go see Alfred Kazin or Norman Podhoretz? I doubt it: but, as literary critics, they made their judgments. Sherrod was content with quoting Royal as saying of the Shaw book, “Part of it is true, part of it is opinion, and part of it is lies.” Had Sherrod asked Royal to identify the lies? “Well, when I asked him about that he said he hadn’t read the book—that one of his assistants advised him not to.” That, in itself, would appear to be a fair-sized whopper of a story—COACH DAMNS UNREAD BOOK—and one can imagine how harshly Sherrod might have chastised one of his own reporters for failing to recognize it.

Blackie heatedly defends himself against suggestions that he might not aggressively go after the soft underbelly of sports, or write of its darker side. “I fought management for a week trying to get the Lance Rentzel story into the paper. The Cowboy front office was trying to cover up that Rentzel had exposed himself to a little girl. I called the judge in Saint Paul who’d handled the first Rentzel case, and he told me a lot the newspaper was afraid to use. I said, ‘Screw it, let him sue us. Then we’ll really have a story.’ But they wouldn’t. Then the club got Bob Strauss, the Democratic party lawyer on the case. The damn judge clammed up. Meanwhile, I’d been crying and screaming and fighting to get it in the paper and I told the big boys, ‘God-dammit, we’re gonna wind up eatin’ this story and looking like hell.’ We ran a straight story when the charges were filed on Rentzel a week later, but I’d tried to do better.”

Sherrod aggressively covered SMU’s dismissal of players for using drugs and is now working on a similar story involving other Southwest Conference schools. Precious little had been originated, however, about the crass way pro clubs have winked at—or actually encouraged—the use of pain-killing shots, amphetamines, or other uppers for years and years.

Racism? “Sure,” Sherrod says. “I think every club in pro sports has a race problem — except maybe the Golden State Warriors, where everybody but Rick Barry is black. We’ve covered it in depth. Mel Renfro filing a law suit against a discriminating apartment house in Dallas. Calvin Hill had a great deal to say of racism. Now I don’t—and I never have—believe that ball clubs stack blacks at given positions so as to enforce a quota system. In other words, to be sure that no more than X number of blacks are on the field. Hell, there’s too much big money involved! I’m convinced owners and coaches would play a platoon of cross-eyed Chinamen if they thought it’d help ‘em win.” Maybe it’s all point of view, and perhaps mine is just naturally darker and more suspicious than Sherrod’s, but I sometimes think him myopic where more is involved than the score.

Blackie now commands a baker’s dozen writers, taps out “only” five columns per week as opposed to the six he accomplished for twenty years, travels where he wants when he wants, theoretically need not show at the word factory before 10 a.m., presides over a book-lined corner office of generous proportions, is at least semi-handsomely paid, and serves on the Times Herald board of directors. It was not ever thus.

In his decade at the scabby Fort Worth Press, a now-lapsed Scripps-Howard effort where expense accounts were non-existent and he didn’t dare dispatch a staffer beyond Waco unless he suspected the fellow of independent wealth, Blackie held it altogether with chewing gum and bailing wire and cussing. “I looked for good merchandise cheap,” he remembers. Dan Jenkins, the Sports Illustrated writer and author of the best-selling novel Semi-Tough, was discovered in the pages of his high school paper. Blackie lured him from the Paschal Pantherette for a zinging $15 per week, and Jenkins worked his way through TCU without excessive raises. Jenkins recommended a buddy, Edwin (Bud) Shrake, who was put on at “space rates”: this meant he was paid according to piece work performed, as with peapickers and women who take in ironing. After he made $32 in a single week, Shrake was promoted sideways to a full-time staff job at $20 each Friday, the better to conserve corporate funds; Shrake, too, is a Sports Illustrated biggie, a fine novelist, and has sold screenplays. Gary (Jap) Cartwright, currently a novelist and freelance writer, was brought aboard for pennies from a police beat he jazzed up for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Julian Read, long hired for princely sums by Texas politicos who wish their public images polished, once was a $12.50-per-week “go-fer” for Blackie. Jerre R. Todd, now a Fort Worth public relations man, was another of Blackie’s wild and literally hungry crew. Sherrod still considers Todd the big one that got away: “He might have been better than any of us if a living wage hadn’t been so dad-gummed important to him.”

At 55, Sherrod is ripe enough to indulge in old men’s laments. “It ain’t as much fun as it was,” he admits. “I think I give it as much — I just don’t get as much back. I’ll always have a soft spot for that bunch of raging mad paupers at the Press. You could hollar out, ‘Who was the first mate on the Bounty?’ and so many voices would beller ‘Fletcher Christian’ that you thought the Mormon Tabernacle Choir had sneaked up on you. Now, though, you ask most newsmen who Fletcher Christian was and somebody will say, ‘Didn’t he play for the White Sox?’ Nobody reads anymore.”

It does not impress Sherrod that more books are bought than ever before, or that the educational norm — even among out-at-elbows newsmen — is several degrees higher than twenty years ago. No sir, he knows what he knows, remembers what he remembers, and unless you want your nasty statistical mouth mashed you’d better shut it. “We read aloud to each other in the newsroom,” he recalls. “S. J. Perelman and H. Allen Smith and Damon Runyon. Mark Twain. Name ‘em. And even when we were out drinking, or riding on a Texas League baseball train, we talked about writing headlines or leads or makeup. Now, I dunno, the five o’clock whistle blows and everybody runs off to PTA meetings or to mow their lawns.”

Blackie is sprawled in his fine home in the Lakewood section of Dallas, surrounded by so many autographed pictures from people like Bing Crosby and John Connally and Doak Walker that you wonder why he needs wallpaper; he is grinning in remembering when nobody ran off to PTA meetings after work. “There was this beer-sop Meskin food place called Shanghai Jimmy’s, and if we didn’t eat there two nights a week our faces would break out. A certain eatin’ contest was matched between Bad Hair Bentley, who could eat a boiled child if it was free, and a challenger named Pete Fisher, who claimed to eat raw frogs. Bad Hair’s manager tried a tad of strategy that backfired: he had Bad Hair eat rum balls between official courses on the theory it would cool off his gizzard and keep him fresh. When the contest ended in a tie, Bad Hair Bentley claimed he’d been done in by mismanagement. Then somebody noticed that Bud Shrake, who’d been standing around as a mere spectator, had accidentally scarfed down four double-number-elevens. I think Bud was a little embarrassed by being crowned the new official glutton, but after that we’d have him go down to Shanghai Jimmy’s occasionally and eat an exhibition.

“Jerre Todd, the good crazy bastard, he’d do anything a monkey could. You had to watch him. The best sports writing in America was wild stuff he’d write and post on the bulletin board. Back during the Fifties when Red Grange was on TV as a football color man, Red used the worst grammar in the Kingdom, ‘Ohio State they’ and ‘The Buckeyes it,’ and so on. When Grange’s old college coach died—Bob Zuppke, I think it was—I was turning through the Press after the first edition rolled and came on this suspicious dateline from Florida quoting Red Grange as saying, ‘It are a great personal loss.’ Well, shit, I howled and slapped my leg and hated like the devil to make Jerre remove his priceless little invention before the second edition. But, of course, I had to.

“Dan Jenkins was, and is, the most effortless writer I’ve ever know. And the most confident. Most writers, they’re insecure to the point of hiding under the bed. Dan always had the attitude of a competent athlete—and he was a good athlete. Golf. Basketball. Pool. I think he could’ve roped buffaloes. Nothing in the world spooked Dan except snakes. Just a picture of a reptile would crater him. We spent a lot of time finding snake pictures—in color if possible—and trimming them and then rolling them up in Dan’s typewriter. He’d come sailing in, smoking his nineteenth cigarette of the morning and drinking his twelfth Coke. When he rolled his typewriter carriage, out would jump this horrible goddamn snake. And Dan would beat and thresh and whoop awhile and fall down in wastebaskets. Then he’d sigh and sit down and once he’d quit trembling he’d write you the best eight hundred newspaper words you ever read.

“When I left the Press for the Times Herald, Jenkins replaced me as a sports editor there—which was about like being the lookout at a prairie dog colony. Anyway, Shrake made the move to Dallas with me: he and Jerre Todd flipped for it, and I guess Shrake lost. We’d been accustomed to mighty short rations at the Press. Honest, when pencils wore down to nubs you were expected to tape the two shorties together and make-do with the lead at both ends. Then you had to turn in the nubs to get a new pencil. On the second day the Times Herald Shrake said in some wonder, ‘Do you know they’ve got a supply room back there and you can get anything you want?’ He talked like they had a company whore hid back there. When he found out they actually had a copy boy, I thought he’d soil hisself. Shrake would rare back about every twenty minutes and beller ‘Copy!’ and sit and grin silly and look vastly pleased when the copy boy rushed up. Of course, more than half the time he didn’t have any copy. I had to make him quit it so they wouldn’t think we were a couple of Cowtown hicks.”

Dan Jenkins sat in his penthouse apartment on Park Avenue, looking out on the spires of Manhattan. He and some visiting Texas pals cleaned up on chicken-fried steaks which his wife, June, cooks better than they do it at Odessa’s Club Cafe. Bud Shrake, visiting from Austin, opined that the cream gravy was lighter and better than any French chef’s sauce. It was a good time, between sips of wine and puffs of fine cigars, to recall the tougher days—their root beginnings as writers.

“Blackie was a great disciplinarian,” Jenkins said. “I always thought he’d make a good football coach. He commanded respect. I was scared to death of him at first. My first story, I spent all night writing it at home on the kitchen table—cutting, polishing, making it bright. Blackie read the first paragraph and said, ‘Don’t ever write a morning lead for an afternoon newspaper, dumb ass.’ I was crushed. He was never really abusive, but . . well, he bit his words off. It was intimidating.”

Shrake said, “I remember racing to work in the dark and the cold, my hands sweating on the steering wheel, and just knowing that no matter how many red lights I ran it wouldn’t be enough for Blackie. Anything past 5:30 a.m. was considered late, and he dearly despised tardiness.”

“God,” Jenkins said, “but he could make you feel like a worthless shit. Wouldn’t speak to you if you came in late. Just freeze you out. He’d grab everything out of your hands and do it himself. One of the day’s highlights was going to breakfast with Blackie after all copy was in. But if you’d been late you didn’t get invited. You’d sit there alone, hating yourself and vowing never to screw up again.”

“When he was really pissed,” Shrake said, “he’d make you telephone Jess Neely at Rice or Dutch Meyer at TCU and ask some simple-ass question before good daylight. They had personalities somewhere between barracudas and mad bears, and they’d cuss you like they’d invented it.”

“Couldn’t fake it either,” Jenkins said. “Blackie would stand right over you.”

“Jap Cartwright was on time once in two years,” Shrake said. “If it had been us, Blackie would have built us doghouses with our names on ‘em.”

“Jap don’t have the normal human responses,” Jenkins grinned. “I think Blackie would have cracked before Jap did.”

Why do so many alumni of Blackie Sherrod’s School of Newspapering still swear by him?

“He was the best,” Jenkins said. “A great teacher. Blackie was doing things with headlines and makeup that other Texas papers didn’t begin for twenty years. He taught punch and juice. ‘Make me read this story,’ he’d say. ‘Motivate me.’ He taught you to look for the angle, and if you didn’t have a strong angle you jazzed it up with similes. He carried his own little black book of original similes around, even when he was drinking, and he’d jot ‘em down as they came to him. Things like ‘. . . as out of place as a Chinaman at the opera.’ A Forth Worth pitcher, Bob Austin, pitched a no-hitter and Blackie wrote a headline saying WHY DON’T WE NAME THE STATE CAPITOL AFTER HIM?

“He taught us that we couldn’t compete with the Star-Telegram when it came to money or numbers, that we had to out-write the opposition and out-hustle ‘em. He made you work. Every time you looked up he was standing there saying ‘What are you working on now?’ Blackie didn’t believe in an idle minute.When we weren’t working or reading to each other, he’d organize track meets. Chinning contests in the men’s room. Fifty-yard dashes on the way to breakfast. Push-ups and broad jumping and arm wrestling. I believe we’d have pole-vaulted if Blackie’d had the equipment.”

Shrake said, “He had a fit when we got careless. Because of our cheapo operation at the Press, we’d clip baseball box scores out of the Star-Telegram and reset ‘em. One time they trapped us by inserting names from our own staff: Ervin, P. and Jenkins, D. Like that. Well, we didn’t notice it and ran ‘em and it was really humiliating. When Blackie came back from a trip with the Fort Worth Cats he was furious. I said, ‘Blackie, we’ve always done that.’ And he said, ‘Yes, goddammit, we have to. But because we’re broke don’t mean shouldn’t always be alert.’”

The old grads of Sherrod University were laughing now, safe from the terrors and poverties of youth; their memories grew warmer and perhaps a shade maudlin. Blackie telling funny stories after “fifty or sixty beers.” Blackie singing “Danny Boy” or “Heart of My Heart” or “Ace in the Hole.” Marilyn Sherrod cooking great meals for Blackie’s boys and mending their broken hearts and generally picking them up when they were down. Newsroom horse play. Betting on football picks in the office pool. “We were a family,” Jenkins said. “A fraternity. It was us against the rest of the paper, us against the opposition, us against the Establishment, us against the world.” Shrake said, “Blackie’s always been an old-fashioned man. Duty. Honor. Country. When the original Dallas Texans began [in 1952], he thought so little of pro football that he assigned coverage to his most junior writer. He takes a lot of convincing before he’ll change.”

The beautiful June Jenkins had been listening with a growing smile. Now she said, “Do you guys remember how you used to hate him?”

They looked at her as if she’d announced her intention to dispense her special favors to the next man who might come up in the elevator, or maybe wanted to surrender all Semi-Tough profits to Russian War Relief. Shock. Disbelief. Bugged eyes and slack jaws.

“Hate Blackie?” Jenkins managed. “Shit, we never hated Blackie! Impossible!”

“You don’t remember throwing your hats down and jumping on them and cursing?”

“Well . . .”

“Because,” she smiled, “you were overworked and underpaid?”

“Oh, well, shit,” Shrake said. “Everybody did that. It was just blowing off steam.”

June Jenkins laughed and said, “Look, I love Blackie Sherrod, too. I just wanted you to remember it straight.”

Shrake looked a little sheepish and said, “I do remember resenting covering a football game in Waco on Christmas Day.”

“Well,” Jenkins said, “maybe sometimes I hated him about fifteen cents worth my ownself. But when you were good he let you know it, and it made you want to be good again real soon. He taught us to write our way of Fort Worth, didn’t he?”

“Why, I was never mean to those precious children!” Blackie Sherrod says.

We are at the house he enjoys calling “Harlow’s Haven” because of its resemblance to Hollywood homes in the Thirties and Forties: random curved walls of thick glass brick, skylights, air and space, unexpected staircases. It is late. We weave like twin buoys in choppy waters, near Sherrod’s placid swimming pool, having earlier eaten chili “guaranteed to make your head sweat” and then mangling a few fundamentalist hymns with Blackie the perpetrator of much marginal guitar.

“With people like Shrake and Jenkins I didn’t need to be mean. They were hard-working buggers. They cared and they hustled and they’d make you wake up singing. Things we had to guard against was showing scorn toward anybody who couldn’t write good. For a bunch of nobodies working on a Mickey Mouse newspaper we were terrible talent snobs.

“I always taught young folks to write not in competition with others but against the highest standards. Jap Cartwright, when he went to work for the Dallas News writing a column like mine in the Times Herald, he said, ‘Blackie, I’m gonna wear you out. Gonna work so hard and good you’ll never beat me.’ I really didn’t understand that. If I did my best work, then I knew I wouldn’t have to worry about Cartwright or Red Smith or the ghost of Granny Rice. If I didn’t . . .”

He sucked on a Budweiser bottle and said, “I do plead guilty to being a damned meddler. Can’t keep my hands off things. When I leave town and come back and go through the papers, I yell and fuss no matter what’s been done.”

Did his subordinates resent it?

“Shit, I imagine. Wouldn’t you? I know I would. I just can’t seem to help it: didn’t learn to delegate nothing until my ninety-eighth birthday. It pisses me off when something’s not done right! Awhile back I returned from a trip and Lee Trevino had just won a big golf tournament. And I asked, ‘Has anybody called him?’ They mumbled awhile and somebody said, ‘Well, we didn’t know how to reach him.’ Now, come on, the man lives in El Paso not in Afghanistan.” He broods and sighs and shakes his head over mortal man’s capacity to err. “Bob Galt’s good, and steady as a rock. Got a kid named Randy Harvey with all the earmarks if he’ll stick with it.”

Where do sports fit in the grand scheme?

“It ain’t war or pestilence or famine. I guess you could say it’s all running and jumping. I like sports, always have. Played ‘em all at Belton High School. Tried a little football at Baylor and Howard Payne. I try to keep sports in perspective. I’ve written other things and feel comfortable doing it. But long ago I made a decision to stay with what I’m doing. It sure does beat a sharp stick in the eye.” He says this as one who has pissanted heavy objects for small profits and began on the Temple Daily Telegram as the Belton correspondent. Without pay.

Sherrod agitates his Budweiser dregs and talks of way back when: “I always loved words. Read every book in the Belton library. Two books a day in summer and still had time for baseball. The librarian had a rule that kids couldn’t check out adult books but she finally made an exception. I read Twain, Zane Grey, William MacLeod Raine. History, biography novels. These old Street and Smith football magazines, hell I memorized them.

“Generally, I’ve found athletes and coaches to be purty good companions. Bobby Bragan, the old Forth Worth Cats manager, knew newspapering as well as he knew baseball. He’d give young newsmen angles: ‘Well, that San Antonio second baseman has hit in fifteen straight games’ or ‘This left-hander hasn’t gone more than three innings against us in two years.” I admired his competence. Lindy Berry, the old TCU quarterback, is still one of my best friends. Quality folk. Lot of old jocks keep in touch. I had a note this week from a kid who played only one season with the Dallas Cowboys maybe ten years ago.

“Pro jocks, lately, they bore my ass off. They’re so damned spoiled. But, hell, it’s not really their fault. Since superhumans started coming along—kids weighing three hundred pounds and standing eleven-feet-seven by sixth grade—they’ve been coddled and cheered and had their butts wiped. I don’t find ‘em very interesting people, no matter how many quarterbacks they can strangle or how hard they can throw a baseball.”

Sherrod came from poor but proud stock, the son of a barber father and a music teacher mother. Though handsome and a star athlete—he likes to remember catching the pass that beat Cameron 7-0 and won Belton a district championship in the late Thirties—he was not a swaggering hotshot. “I had a spit curl,” he said. “But no car. My old man kept at me to excel. I never played a game that wholly satisfied him.”

The kid always had some kind of sweaty job, and learned about hard-scrabble. The work ethic stuck deep in his craw. To this day he is not fond of welfare loafers and is contemptuous of people who give less than their best. Sherrod was discharged from the Navy on the last day of 1945, after winning decorations as a tail gunner in the Pacific, and returned to the Temple Daily Telegram to find that George Dolan (now a Star-Telegram columnist) “had got my job and my girlfriend.” Walter Humphrey, the late editor of the Fort Worth Press, who had been on the Temple newspaper earlier, brought Sherrod to Cowtown in 1946. After writing news for radio station KFJZ and doing a police beat stint for the Press, Blackie wrote sports under Pop Boone and then Amos Melton. Blackie became sports editor in the early Fifties. “After ten years on the short end of the stick,” he says, “I cleverly realized the Press was a dead end. I was offered jobs in Houston, San Diego, and here in Dallas. I 1958 I met the Times Herald representatives in the back booth of a Howard Johnson’s, like we were a bunch of spies, and when they offered me $185 a week I run over ‘em rushing home to pack. The Press had been paying me a figure that would embarrass my mother.”

“He’s not the world’s easiest person to live with,” Marilyn Sherrod says. She is a pleasant blonde woman who loves poodles, cooking, and the man she’s been married to for 28 years. She was a secretary at the Press when they met. “Blackie’s always been so consumed by his work that sometimes I fear he’s missed a few things. First date we had he took me to a football game. I learned early what it was like to be a press-box widow.

“At first we didn’t want any children. We had careers and needed to get established financially. And then it happened that we just never got around to having any. I guess that’s our big regret. One night some friends remarked on all the honors Blackie’s won—(she laughs, “I always say we’re in the used plaque and scroll business”)—and Blackie said, ‘What are we gonna do with ‘em? There’s nobody to leave ‘em to. What good are they?

“But I don’t think he’d trade lives with anybody. He’s proud, you know. He’s an achiever. He goes all out at what he does and he’s not happy unless he’s making something happen. ‘Old Buster,’ as he calls himself, has never bored me. Ever.”

Bob Galt, long Sherrod’s right hand at the Times Herald, claims his boss is a pussycat. “He tries to come on hard and tough, but he’s got this compassion for people and animals. I could tell you yarns for hours. Yeah, he bitches and complains some. It’s his job and his nature. But he’s the greatest journalism teacher in the world.”

I told Sherrod that nobody had said anything bad of him. (The nearest thing to a knock came from the person who said Sherrod may be an old-fashioned, if unconscious, bigot: he was among the last to abandon calling Muhammad Ali by his old name of Cassius Clay and sometimes he’ll still say “colored boy.”) “Well, yeah,” Sherrod said. “You sure ought to talk to my enemies.”

Well, who are they?

“Screw you,” he said. “Get your own story.”

Blackie is Beautiful

“Sportswriting is like driving a taxi.”

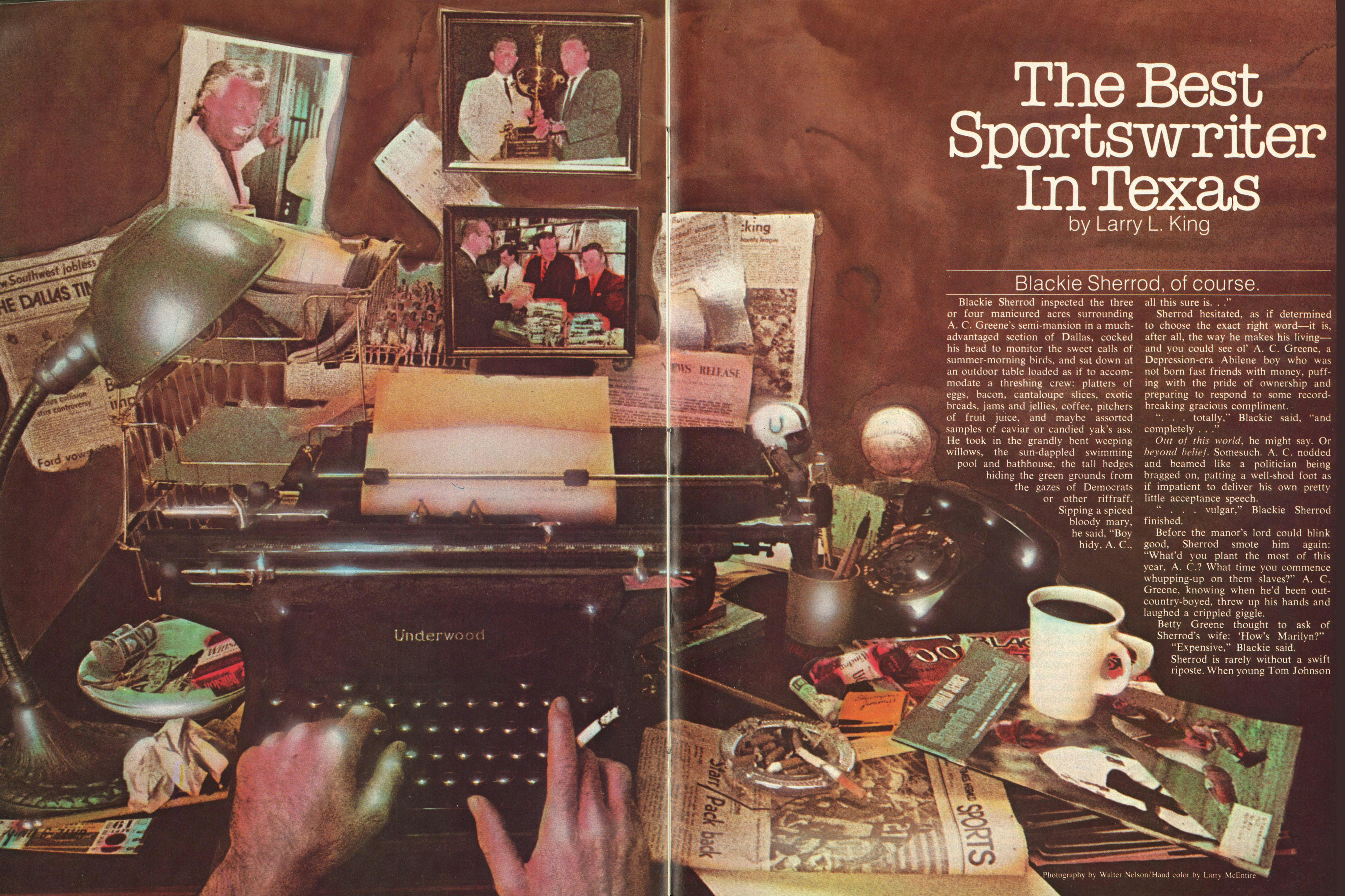

Good editors such as Blackie Sherrod instruct writers to show, not merely tell. Very well. Here are random samples of Sherrod’s talent, culled from his new book Scattershooting.

On the Dallas Cowboys beating the Miami Dolphins in the 1972 Super Bowl:

“The ghosts are now buried and quiet, the closets have been swept clean of skeletons. The Cowboy complexion is now clear of pimples, and they may walk down the street on the day after their biggest challenge without yard dogs barking and small boys pelting them with stones. The old brands of Choke City, U.S.A., and the El Foldo Kids and the Next Year’s Champions must now fall on other brows. The Cowboys have met the big one and he is finally theirs. . . . The clock told the story. Dallas controlled the ball 40 minutes and 58 seconds of the game. This left 19 minutes and two seconds for the young Dolphins, and this was like trying to vault the Eiffel Tower with a broomstick. . . . Some Shadetree Experts called it a dull game because of Dallas’ grinding movements, but it is like putting the bad rap on a no-hitter because there were no home runs…”

On recalling that marvelous season when undefeated Belton whacked Cameron for the district championship:

“The Belton team was a slight underdog because word leaked out the Cameron team had married guys on it. No one knew exactly what advantage this was, but it was impressive news. . . . Merchants in both towns closed their doors. The drug store sold out of cigars, and several of the sportier chaps made a run down to Williamson County for pints of Mint Springs. There was a report that the owner of the all-night cafe had bet $50. . . . Cameron had run a special train for the game, a distance of at least 30 miles or so. People stood a half-dozen deep around the field and some perched in trees . . . at one end of the arena. Talk about pressure, Don [Meredith] baby, you never had it like this.”

Describing Johnny Unitas:

“His face is a map of a hard path, forehead wrinkles, cascading furrows in his cheeks, small pock marks dotting his lean, serious cheeks. He is a day laborer who somehow fell into fame on his way to work and it impresses him not one whit.”

And:

“Sportswriting is just like driving a taxi. It ain’t the work you enjoy. It’s the people you run into.”

Or:

“Something less than two weeks ago, Mr. LBJ thru his laig crost the saddle horn and made oratorical history. He spoke a line that zinged in the national ear. Zinged, baby, zinged. Our leader surveyed reports from [Watts] and released this ponderous thought: “‘Killing, rioting, and looting are contrary to the best traditions of this country.’ Not only was this of informative value but it showed a vast amount of diligent research.

Finally, on writing of a dying Primo Carnera, the mob-managed innocent giant heavyweight who in the thirties was fed setups until he became a bogus champion, then—once the mob had its bets placed—was sent out to take fearful beatings from Max Baer and Joe Louis:

“He had zero ability but he was heavy on bravery and pride. And when he left the New York airport, his frame wracked by cirrhosis of the liver, heading home [to Italy] to die, the photographers clustered about him. A couple of his old sparring mates came to see him off and they were openly crying. Primo begged the photographers to wait a minute. Then he handed his cane to a friend and told the guys to shoot away. He still wanted no sign of weakness. May somebody forgive all of us everywhere for what we did to this human being.”

I reckon you can see, now, why those of us who peddle words talk about Blackie Sherrod on our barstools and find him so easy to steal from. In the second paragraph of this opus I wrote that A.C. Greene “was not born fast friends with money.” My earlier efforts said things like, “He was born scratch poor” or “He came into this world naked and broke,” and so on, none of it working. Then, thumbing through the galley proofs of Scattershooting, I found the line “Unitas is fast friends with money,” and I simply couldn’t resist the slight twist. I’m like the Texas legislator who said in response to the little old lady constituent who’d charge that she’d heard he was stealing, “Yessum, but I been trying to quit.” Me too, Blackie. But you sure do make it hard. — L.L.K.