The task of writing a culinary memoir troubles even the most talented chefs and writers. The venture proved especially difficult for Louis Lambert, who shied away from the endeavor for years, because he never knew what version of his story he wanted to tell. Would he talk about the childhood memories of his West Texas family and their legacy of cattle ranching, or would he reflect upon years of cooking in the confines of his professional and personal kitchens?

One thing was certain: if Lambert was going to write a cookbook, it had to be from the soul, and more than just bound pages of strict directions, rough estimates of temperature settings, and lists of never-ending ingredients. It would have to be a reflection of his West Texas roots as well as recollections of cooking thousands upon thousands of dishes for Texans across the state.

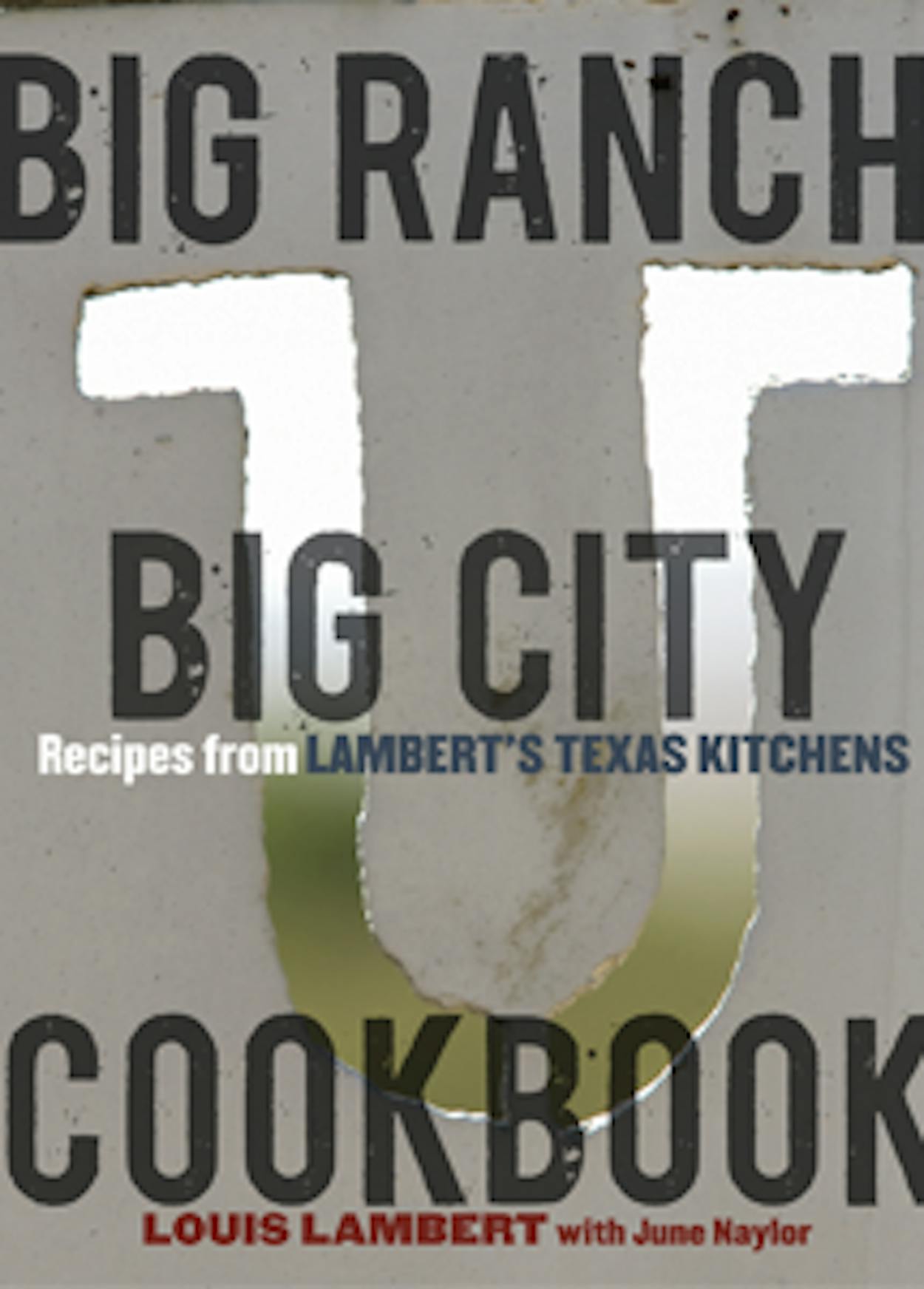

Behold: Big Ranch, Big City (Ten Speed Press, $40). The work of a cook who escaped from the West and migrated to the “big city,” only to hear his roots calling him back home. Forgive me for giving away the end, but he eventually returns and becomes one of the masters of authentic Texas cuisine. With the help of June Naylor, Lambert has put together a cookbook that pays homage to his whole culinary story.

Why is now the time to put out a cookbook?

Over the years, I had been approached by different people to do a book, and at the time, I did not feel like I had a voice or a desire to put something together. I had plenty of material and recipes, but I wasn’t ready to go through the process just for the sake of saying, “I did a book.” What changed is that I felt I had reached a point in my life that I had not just recipes to share, but more of a philosophy of cooking and the stories behind why I cook the way I do.

You say that this book is partly a memoir. Do you feel like that’s an important thing to include in cookbooks nowadays?

That’s why I never really had the desire to write the book, because I just didn’t want to do a compilation of recipes. But I think I hit the point in my career where I had more than just recipes to share with the reader. Anybody who likes to cook has similar stories of where they came from.

Tell me a little bit about the title.

Growing up in Odessa and coming from a family of ranchers in West Texas, that was my culture and heritage. At the same time, I trained at the Culinary Institute of America [in New York] and worked in San Francisco in what we laughingly call “the big city.” My cooking is a culmination of my West Texas heritage and my experience in big-city dining. We all do foods that have meaning from growing up, but we also grow an appreciation for other foods through the years. It was my tribute to both sides.

It’s neat that you can appreciate going away for a while and returning home to your roots.

Yeah, I never ran away from who I am or what it meant to grow up in West Texas, but like most well-known chefs, you are searching for who you are. I had dreams of the big city life and fine dining, but as I grew, I was struck by the fact that we have just as much culture and heritage in Texas as anywhere else I’ve been.

Through the years, you have cooked thousands of dishes. How do you ultimately decide what goes into a cookbook like this?

It’s tough. It’s very tough to sit down and try to define who you are with a cookbook. What I tried to do was do a combination or representation of foods we do in the restaurant, foods I grew up eating, and what I cook at home now. In doing that, I wanted to give readers recipes that are more challenging, with complicated cooking methods that we do in the restaurant, as well as very approachable recipes that I’ll throw together when I’m cooking for my family and friends now, like the Cheddar and Corn Pudding or Tamale Gratin.

Were there any classic cookbooks you looked at during the writing process for creative inspiration?

I’ve been collecting cookbooks going on fifteen years. My office is cluttered with them. I love collecting old, vintage cookbooks. So when we were putting this together, I had in my mind what I wanted the content to be, but as far as how the recipes are written, I referenced a bunch of books. There is a book I referenced called The River Cafe Cookbook by Rose Grey and Ruth Rogers. I loved the feel of that book because it was approachable and they portrayed the feeling that you were in the kitchen with them.

What has mattered more to your career as a Texas chef: the classical training you have honed over the years or the fact that you were born in Texas, raised in Texas, and came back to it?

Most of the chefs I have respect for and that do a great job with the food they put on their plates cook from their life experiences. For me, what is more important is to be true to who you are as a cook. I’ve worked with a lot of folks that are classically trained, that have gone to culinary school, and worked in big city restaurants, but that is not as important as knowing who you are as a chef and integrating that into your cooking. Larry McGuire and Tommy Moorman run Lamberts Downtown Barbecue, and none of them are classically trained, but I think they are two of the best chefs in the country. They are cooking from their life experiences and cook foods that they love to cook.

You went away to New York and San Francisco for a while. Was there ever a time you thought about not coming back to Texas?

I never had the decision ‘I’m not coming back,’ but growing up in a small town like Odessa, you want to get out and stretch your wings. It was not my intent when I went to New York and California that I was doing this to return back to Texas. It’s more of an ‘I’m going to go out there to see what’s out there.’

Do you ever feel limited in specifically making “Texas food?”

No, because I view Texas food as being so much more than beef and barbecue. Where I grew up, of course you have that region of barbecue and beef, but you have influences from all over. You’ve got Mexico just south of there. Make your way around the state and go to the plains of East Texas, and you’ve got more Southern cooking. You go to Beaumont and Port Arthur, and you’ve got a heavy Cajun influence. You go to Austin or the Hill Country, and you’ve got more of that German influence. So, you really can cook anything and still be true to Texas roots.

In becoming more popular through the years, did you ever fear that your restaurants would ever become too commercial? How do you maintain the integrity of your cuisine, amidst all of its popularity?

The first restaurant I opened in Austin was Lamberts on South Congress [Avenue, in Austin]. It was a small restaurant, around thirty-five seats. When we opened, it was not our goal to go out and get press for bedazzling. It was to truly do the foods that we wanted to cook on a daily basis and stay true to who we are. What I found was we got a lot of fame because we were staying true to who we were as chefs. Can it be done? Yes, but you have to walk in every day and make sure the quality is there.

What do you think it is that put your restaurants on the map?

The attention to detail and doing foods that people love to eat. That sounds simple, but it’s, again, not taking yourself so seriously that you try and teach people what they need and should want to eat. I’ve seen too many chefs go into restaurants that are unsuccessful, and their reply is, “Well, if my customers only could understand what I’m trying to do.” You lose focus when you blame it on the eaters. And, we are in Texas, so people want to eat steaks, barbecue, and all the things that come with it.

Were there any recipes in the book that you had trouble divulging?

I’ll give up any recipe. That’s not going to keep anyone from coming in and eating at the restaurant. People come in to eat at the restaurant because they don’t want to stand in the kitchen and cook on their own. I have no problem giving any away.

How have you seen Texas cuisine evolve over the years?

More restaurants are taking the time to produce everything in-house, like we have from the very beginning. Consumers and diners are more educated now than ever before, so they want to know where their food comes from and how it has been prepared. A more educated diner means they recognize the extra step chefs have put into it. When we first started, we were some of the first and only ones that did everything from scratch, from making our own sausages, our own sauces, and smoking everything in-house.

How do you integrate the current trends into classical Texas cooking?

I’m old enough to remember the start of Southwestern cuisine. There are still some of those guys around that were doing Southwestern cuisine when it was the hottest rage, such as Dean Fearing and Stephan Pyles. It became the hot food trend of the time. I looked at that and thought it was somewhat silly because I grew up in the Southwest, and the food they were doing wasn’t rooted in our culture and heritage, even though they were using some of the ingredients that we would use. Most of the chefs I admire are trying to stay true to the foods and the culture and history of the foods that I associate with Texas. The challenge with that is that they don’t go overboard with the food, like they did earlier with Southwestern cuisine, where they are taking it away from what it truly is. You don’t want to improvise on recipes and make it so fancy that the food loses its soul.

What do you see over the horizon for Texas cuisine? Do you think things like food trucks will still continue to grow, or do you see something else coming up?

I hate to even acknowledge food trucks. I think food trucks will run their course. The market is getting overcrowded, and I don’t think it can sustain itself. As customers are becoming more educated, they are not going to want to see gimmicks. What they really want to see is more of what we are doing, point of origin, and where their foods are coming from. It’s hard to do now because the economics aren’t there to support it. When we first opened Jo’s, we wanted to use all natural, but then there wasn’t a source for all natural beef. Now that customers over the years have demanded it, there are a lot of producers doing all natural beef. Restaurants are driven by what people are doing in their homes. People weren’t demanding organic until they started cooking at home that way.

You have restaurants in both Austin and Fort Worth. Which city do you feel more home in?

As for day-to-day living, Fort Worth. It’s got such great culture, but at the same time it’s slower-paced. It’s more livable. To me, Fort Worth is what Austin was like ten, fifteen years ago. As far as the food scene, hands down, Austin’s food scene is miles ahead of anybody in the state of Texas because you have the university, the Capitol, and the high-tech industry. Because you have such diverse groups living there, you have people craving new and innovative things. I think that translates into a great food city.

At this point in your career, do you feel like you have a firm understanding and grasp of Texas cuisine, or is that something you are always learning from?

You are always learning, and the worst mistake a chef can make is to think that they know more than anybody. Everyday I walk into the kitchen, my eyes are opened to not just dishes, but also new ingredients and new ways of doing things. I’ve learned more from watching dishwashers throw together family meals at the restaurant than I have in four-star restaurants.

What can we expect from you or your restaurants in the coming years?

I want to be able to personally take the time to travel around the state and get to know the state food scene a little bit better. Not just the new hip restaurants, but also the tried-and-true restaurants and the geography and culture of its people. It’s exciting to be at that point in my career where I can see and learn more. I want to do another cookbook because I really enjoyed that process. As far as restaurants, I would like to do something a little bit smaller. Something small scale like the original Lamberts from way back when. I would like to touch every plate and get to know my customers.