LIKE MANY ELECTION CAMPAIGNS LAST FALL, the race in Colorado’s Seventh Congressional District between Democrat Ed Perlmutter and Republican Rick O’Donnell was a bruising affair. Personal attacks and negative advertising were the order of the day. According to Perlmutter, O’Donnell was a right-winger with dangerous ideas who wanted to privatize Social Security, while pro-O’Donnell ads attacked Perlmutter for being soft on immigration. One such thirty-second spot was especially pointed, claiming that, as state senator, “Ed Perlmutter sponsored legislation giving taxpayer money to illegal immigrants.”

On its face, this ad seemed typical, one of thousands run last fall in an unusually hostile political season. Closer inspection, however, revealed that the ad was, on just about every level one can imagine, not what it seemed. For one thing, it wasn’t true. The legislation that Perlmutter sponsored did concern taxpayer-funded benefits, but they were for legal immigrants, not illegal ones. The casual viewer might also have assumed that the advertisement had been produced by or in cooperation with O’Donnell’s campaign. But his staff had nothing to do with its content, nor was it produced or financed within a thousand miles of Colorado. The ad’s genesis, in fact, was a sort of miracle of remote control. Reporters who dug into the story found that funding for the ad had come from a 527 group called Americans for Honesty on Issues (AFHOI). The past several election cycles have seen a large number of these so-called 527’s, which are named after the section of the federal tax code that exempts certain political groups from paying taxes.

Normal campaign finance limits in raising and spending money do not apply to 527’s, a loophole through which millions of dollars have flowed. Due in part to this lack of oversight, 527’s have developed a reputation for being shadowy, and AFHOI was no exception. In 2006 the group produced adversarial television ads in nine congressional races across seven states, but when the press started probing, it seemed to vanish into thin air. Its address was a post office box in a UPS store in Alexandria, Virginia; its “contact” was a conservative political consultant in Houston named Sue Walden who didn’t return calls.Reporters studying the story were unable to determine exactly who had come up with the idea for the ads, who had produced them, or how the Perlmutter-O’Donnell race had been targeted in the first place.

The one thing they did find out was the identity of the man who had pumped $3 million into AFHOI and was its sole benefactor: a wealthy Houston homebuilder named Bob Perry. Perry is the nation’s largest individual political donor. In 2004 and 2006 he gave a total of $29 million to state and federal races. Last year, more than $9 million of that was channeled through three 527’s that aggressively targeted races for the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. In spite of such a massive political presence, Perry is as mysterious as some of the groups he funds. He never talks to the press, rarely appears in public, and remains an inscrutable figure even to people to whom he has given hundreds of thousands of dollars. He might have maintained this relatively low profile indefinitely, except that in 2004 he was the largest funder of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, the controversial 527 that many people credit with derailing John Kerry’s presidential campaign. Almost overnight, Perry became a poster boy for the notion that a cabal of wealthy donors, shady consultants, and unaccountable 527’s was taking over American politics.

Perry first appeared as a real force in Texas politics in 2002, when he dropped $3.8 million into campaigns, most of it aimed at taking over the state legislature and ultimately recarving Texas into Republican-friendly congressional districts—a gambit coordinated by then-House majority leader Tom DeLay and also heavily funded by San Antonio doctor James Leininger and other wealthy Republican donors. He later became the largest single contributor to Governor Rick Perry’s reelection campaign. But in spite of such lavish giving, he is the odd political donor who seems to want none of the conventional perks in exchange for his money. He never attends fundraisers, never calls up candidates to solicit votes, never threatens or cajoles. He has not asked the governor for the usual appointments to state boards that accompany this sort of giving. Nor does he, unlike many other political patrons, demand that certain consultants be used exclusively as conduits or as media contractors.

The money comes, say politicians who get it, without strings. “He has been a major contributor of mine,” says Texas land commissioner Jerry Patterson. “Over the years he has probably donated more than two hundred thousand dollars to my campaigns, and he has never called me. When I was in the Senate, he never called me to vote one way or another or to say, ‘Hey, I would really like you to take a look at this,’ or ‘I am really opposed to that.’ ”

Unseen by the public, uninvolved with his candidates, the most powerful political donor in the nation has until now remained largely an enigma. Few apart from a small circle of close friends in Houston know much about him. What they do know may surprise some people. For instance, Perry favors affirmative action. He has given money to Democrats, particularly black and Latino Democrats. He opposes his party’s hard line on immigration rights. He is a large-scale donor to an inner-city Houston foundation sponsored by a liberal black minister and to an educational scholarship program for Hispanic students founded by a liberal professor. So who is Bob Perry? Is he the monolithic, unyielding, far-right ideologue he is often portrayed to be? A philanthropist who gives generously to causes he believes in? Some hybrid of the two? Almost nobody knows, and that’s the way he likes it.

BEFORE THE SUMMER OF 2004, few people outside the state of Texas had ever even heard of Bob Perry. National fame—or infamy, depending on your political views—did not come until the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth began running its television advertisements opposing John Kerry’s bid for the presidency. Perry became involved the way he often does in political and charitable ventures. The group’s co-founder, John O’Neill, called on him in his office in May 2004 and told him that he had enlisted many of the 23 Swift Boat officers who’d served in Vietnam at the same time Kerry had and 3 out of the 5 commanders who were on the river with Kerry the day he earned his Bronze Star. O’Neill cited Kerry’s 1971 congressional testimony that he had heard of soldiers in Vietnam who had “razed villages in a fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan” and committed “war crimes … on a day-to-day basis,” which O’Neill said falsely implicated the men with whom Kerry had served.O’Neill said that he and the other members of his group were looking to clear their names and bring to public attention Kerry’s testimony. At the time, Swift Boat Veterans for Truth was struggling to support itself and virtually unknown. O’Neill asked for $100,000, which Perry promptly gave him.

As it turned out, the “Swifties” were interested in a great deal more than just clearing their names. They went on to mount one of the most devastating political attacks in American history, beginning with television ads in Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin claiming that Kerry was “no war hero” and that he had “lied to get his Bronze Star.” They later ran ads showing Kerry testifying before Congress about atrocities “committed on a day-to-day basis,” intercut with images of Jane Fonda in Hanoi, and ending with a stamp across Kerry’s face that read “betrayed his country.” The ads were deeply controversial, fueling talk radio, opinion columns, and cable news shows in the months leading up to the election. They were also, according to many media reports, full of inaccuracies and inconsistencies and were contradicted by the Navy’s records. John McCain called them “dishonest and dishonorable” attacks on a war hero, while former senator Robert Dole endorsed them, saying, “Kerry never bled that I know of” and “All these guys on the other side just can’t be Republican liars.” President George W. Bush called his opponent’s war record “admirable” and denounced all third-party campaign ads, without specifically naming the Swift Boat Veterans.

Whatever one thought of the ads, they were startlingly effective, and many people believe they cost Kerry the presidency. Their effect was evident in a September CBS/New York Times poll, showing that an astonishing 60 percent of Americans said that Kerry was “hiding something or mostly lying” about Vietnam. Perry ultimately contributed $4.5 million to the effort. According to his spokesman, Anthony Holm, a principal of the Austin public relations firm the Patriot Group, “He agreed with the [Swift Boat] group’s mission statement and he believed what O’Neill told him and that was why he gave money.”

This very same conviction, however, is the reason many people fear and distrust him. “Perry is a true believer, and he is not too concerned about the means to the end,” says Andrew Wheat, the research director of Texans for Public Justice, a nonprofit group that tracks political giving in Texas. “On a lot of levels, the Swift Boat ads are the height of ludicrous deception. Flogging Kerry for his questionable military valor at a time when he is running against George W. Bush is almost laughable … You might say, ‘Well, maybe [Perry] had the wool pulled over his eyes with the Swift Boats in 2004, but he was back again in 2006 funding these same kinds of attack ads. This is politics at its dirtiest.”

Perry’s Swift Boat donations are typical of a good deal of his giving, which one of his acquaintances describes as “completely binary—the switch is on or the switch is off. He believes in it or he doesn’t.” Once he has decided he likes an idea, he gives massively and without oversight. Beyond putting up the money, Perry had nothing to do with the production of the anti-Kerry ads. Unlike other Texas megadonors, such as the notorious Bo Pilgrim, Perry has never been found at the Capitol, twisting arms before a floor vote on a favored cause. “He gives money because he supports the mission statement of the group,” says Holm. “After that he keeps more than arm’s-length distance. He has nothing to do with the actual activities of the 527.”

Perry’s style of autopilot giving is perfectly suited to the 527 system. Once he’s signed a check, he can leave full control of the message to the consultants and media mavens who make the ads and in effect surrender any responsibility for their content. At the same time, the operatives who run the 527’s—like AFHOI’s Sue Walden—are prevented by law from having anything to do with parties or candidates, which implies a staggering lack of accountability in the system. It is an efficient apparatus, and indeed, almost all of Perry’s giving in the 2006 federal elections—$9.3 million—went to 527’s. The largest of those, the Economic Freedom Fund, to which Perry gave $5 million, funded political advertisements in congressional races in West Virginia, Indiana, Georgia, Iowa, Oregon, Colorado, Idaho, and Nevada. Perry also gave $3 million to AFHOI, which financed races in Indiana, New Mexico, Iowa, Kentucky, Colorado, Arizona, and North Carolina, and $1 million to the Free Enterprise Fund Committee, which funded ads attacking MoveOn.org, a group that supports Democratic causes and candidates.

Almost every television or radio ad and every direct-mail campaign funded by Perry and produced by these 527’s last fall questioned the integrity or record of the Democratic candidate. But for the most part, the charges they leveled were in keeping with the general climate of political hostility that was the by-product of a national dogfight for control of the Senate and House. In their approaches, and their attacking style, the ads financed by Perry were very much like most ads run by Democratic candidates and the 527’s backing them.

There are exceptions, of course. Perhaps the most famous was an ad run against Jon Tester, the Democratic challenger for a Senate seat in Montana. Funded by the Free Enterprise Fund Committee, to whom Perry was the sole donor, the spot purported to be a trailer for a movie. It opened with an image of men on horseback that recalled scenes from Brokeback Mountain, the controversial 2005 film about gay cowboys. The voice-over intoned: “Coming soon: Brokebank Democrats. They can’t fight their nature.” After proclaiming that Tester, who opposes an outright ban on gay marriage, would raise taxes, the ad closed with a cowboy saying, “I guess old Tester just don’t know how to quit … taxin,’ ” a play on the famous line from the film “I wish I knew how to quit you.”

Another recipient of Perry’s largesse, the Economic Freedom Fund, which got the largest single donation to any 527 in the 2006 election cycle, gained notoriety when it was sued by the Indiana attorney general for using illegal “robo-calling” methods. It was also the subject of a complaint filed by the Washington-based Campaign Legal Center to the Federal Election Commission that it had failed to register, as the law requires, as a political committee.

The defense that Perry’s role in all this is simply as a donor of cash rings hollow to some critics, such as Brooks Jackson, the director of FactCheck.org, a Washington-based, nonpartisan, nonprofit consumer advocacy group for voters. “My suspicion is that while he has this convenient excuse that is technically accurate,” says Jackson, “what I suspect is going on is a mental attitude I find among the people who run these independent groups on the left and right. They just don’t care if it is right or wrong. They are so ideologically driven that anything that advances their cause is good and anything that hurts the forces of evil on the other side, that’s okay.”

Holm says the charge is unfair, since not only does Perry have no control over the content of the ads he pays for, but he often doesn’t even watch the ads by the 527’s. “The same is true with his giving to the Republican Governors Association or the Republican National Committee or Progress for America, which represent millions and millions more,” Holm says. “He doesn’t monitor their ads. He just can’t. He is running a business with hundreds of employees. He believes in the mission statement and/or the operators of the organizations. He makes the donation and that’s it.” Perry’s close friend and political ally Dick Weekley offers a refinement on that notion: “If he thinks it’s helping his state or his country, it doesn’t matter to him if he knows the candidates or not. Some don’t even know who he is. How many people that you know would make a contribution to people they have never heard of and never seen? It is a very selfless thing to do.”

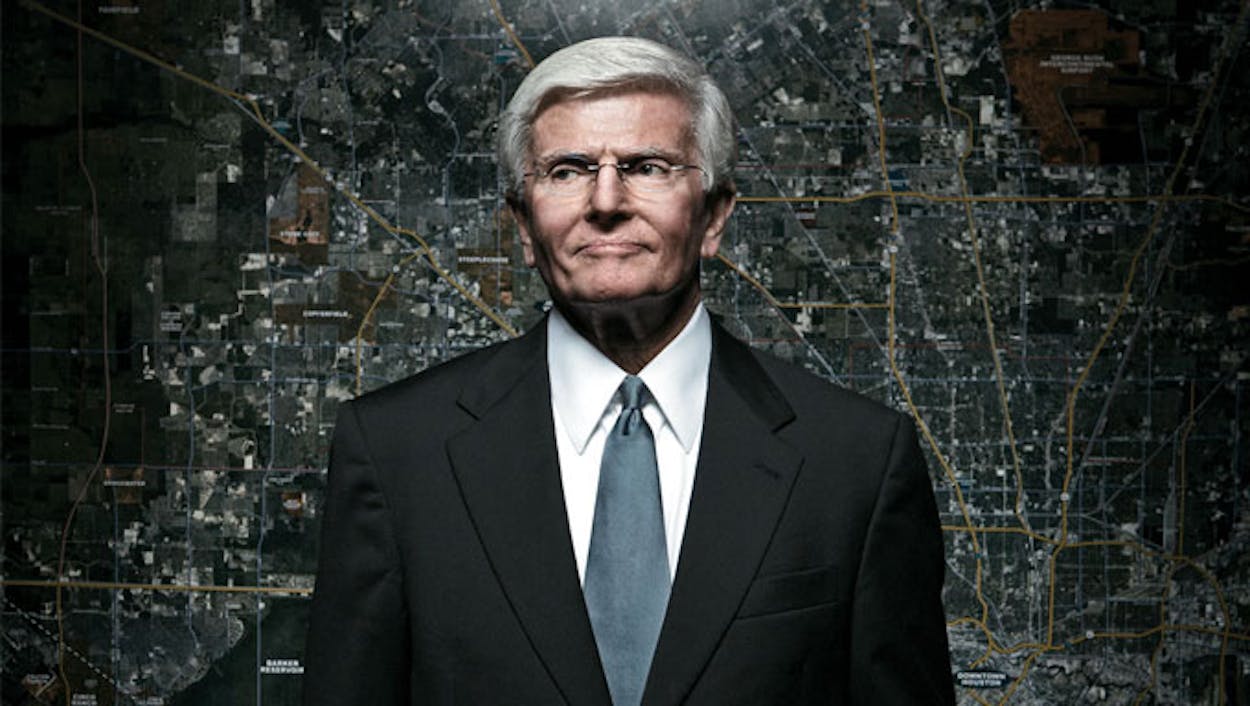

THE DOSSIER ON BOB PERRY is amazingly thin for such a prominent force in American politics. Here are the basics: He is 74 years old, of modest stature but trim, physically fit, and powerfully built, the product of frequent exercise. He played halfback on his high school football team and was known for being “small but fast,” in the words of a classmate. He is handsome, a successful genetic splice of good-looking parents. He is formal, restrained, and wears dark, conservative suits when he is working. Almost everyone addresses him as “Mr. Perry.”

He lives in a stately, 13,874-square-foot, eight-bedroom, dun-colored stucco house with four big pillars in the town of Nassau Bay, southeast of Houston, on a narrow bayou called Clear Creek a few miles from NASA at Clear Lake. He has lived there for thirty years. Aside from a small crop of large homes, the neighborhood is pretty solidly middle class. Nothing fancy. The house is appraised by Harris County at $662,010, though most of the houses around it are in the $200,000 range. He is an ardent pro-lifer and a member of the Nassau Bay Baptist Church. He is not a teetotaler—he drinks a glass of wine socially now and again. He is a proud alumnus of his alma mater, Baylor University. His wife, Doylene, is a former fourth-grade teacher who, after their four children left home, went back and got a master’s degree and then taught at a community college. He exercises daily and is an avid reader of Latin American literature. He likes to tell jokes but tells them badly and then apologizes when they don’t work.

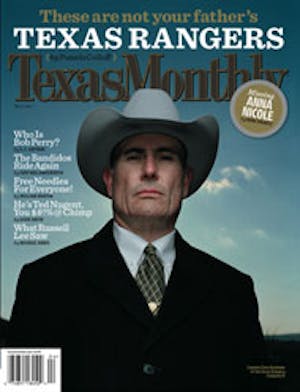

I know all this from looking at photographs of Perry and talking to his friends and acquaintances. I have never actually met with him. To the best of my knowledge, no one in my profession has. Perry’s policy of not talking directly to the press hasn’t changed, but for this story, he did allow me some rudimentary access. I was allowed to ask questions through an intermediary. I was permitted to tour his business, taken to see the exterior of his home, invited to visit certain of his charities, and cleared to speak with several of his friends and close associates. He also allowed texas monthly to photograph him, though I was not there for the session.

Almost everyone I interviewed told me how important Perry’s work is to him. At an age when many people with his wealth would be pitching 9-irons across expensively manicured golf courses, Perry still goes in every day to the drab, undistinguished, three-story building on the Interstate 45 frontage road about a mile and a half from Hobby Airport, where Perry Homes is headquartered. The office practically screams “anonymity.” Inside, there are marble floors and cream-colored walls and a few paintings but little other adornment. The company has been in this location since the early seventies.

During my tour of the building, I was allowed to step inside Perry’s office. He was not present. Predictably, the modestly appointed room offered up little in the way of clues. It contained a desk, a high-backed leather chair, a few aerial maps, and an enormous globe. His view takes in a parking lot, the Lucky Dragon Buffet, a Super 8 Motel, and the elevated concrete columns of I-45. I tried to imagine him on the phone in this office, speaking with the organizers of the Economic Freedom Fund Committee. What does he say? “I’ll put that five-million-dollar check in the mail next week”? Along one wall of the office there was a set of shelves where I expected to find pictures of his family, but the only photo was of Ronald Reagan.

This dreary, paved-over corner of Houston is where all the money comes from. Like everything else about Perry, his company is private, and therefore information on it is scarce. But one can do some primitive triangulation. He founded Perry Homes in 1967 and has slowly built it into the nation’s thirty-fifth-largest homebuilder. In 2005 the company put up 2,688 homes, all in Texas. The houses are mostly traditional, four-square brick affairs, ranging in price from roughly $150,000 to $500,000. These days the company builds both master-planned homes in the suburbs and townhouses in the city. According to Builder magazine’s list of the top one hundred homebuilders in America, Perry Homes has revenues of $593 million. Since profit margins in the industry generally run between 10 and 20 percent, the company likely earns between $59 million and $118 million in net profit every year. This would be the money that Perry, who owns 100 percent of Perry Homes, can use as he pleases. If he chose to sell his company today, it would be worth anywhere between $385 million and $652 million, based on a recent study by the Swiss bank UBS of current valuations in the homebuilding industry. None of Perry’s children are active in the business, but friends say that Perry has been financially generous with them. Still, it seems that, even with $16 million spent on politics in 2006 and uncounted other millions on charity, there is plenty to go around. If he wanted to, he could dump $50 million a year into American politics without breaking a sweat.

Perry did not come from wealth. Not by a long shot. He was born Bobby Jack Perry in a small farmhouse in rural Bosque County in 1932, in a stretch of land northwest of Waco known as the Blackstump Valley. His father, W. C. Perry, was the principal of a small elementary school. In the summers, W. C. picked cotton, labored on construction crews, and pumped gas as he worked his way toward a graduate degree in education from Baylor University. He took a job as principal of Meridian High School in 1943, when his son Bobby was eleven. (W. C. Perry ultimately became dean of men and vice president of student affairs at Baylor, where he had the distinction, in 1967, of expelling his son’s eventual beneficiary, Tom DeLay, for various infractions, including drinking and painting parts of the Texas A&M campus Baylor green.)

Meridian was, by all accounts, a pleasant place to grow up. “Meridian was a farm center, and people did not have a lot of money,” recalls Donna Anderson, a childhood friend of Perry’s, “but it was a friendly town. It was also a very small place. A trip to Waco was a big deal. A trip to Dallas was shooting the moon. Nowadays, Bob and I are world travelers, but the world was a very different place back then.” Though the Perry family was far from wealthy, they owned a trim, modest, stucco house, were the first in town to own a television, and could afford to buy a new car every three years, which they went to Detroit to pick up.

Anderson remembers Perry as a polite kid who was a budding capitalist. “He used to have rabbits,” she says. “My father, who thought the world of him, used to let him have lumber to build rabbit hutches.” Perry raised the rabbits, slaughtered them with a lead pipe, hung them up, skinned them, gutted them, and then sold them.He bought goats and sheep to sell at auctions, hawked melons on the street, and raised and sold banty hens. He also worked at the local hospital and the local food market. He played football and ran track, and friends say he was popular and well liked.

After graduating from high school (his class contained 22 people), Perry attended Baylor, where he majored in history. After graduating, Perry started working as a high school history teacher. He went on to teach and coach football and other sports for the next ten years in San Angelo and the Waco area. During the summers, he toiled on construction crews, and in 1965 he ended up in Houston working for established homebuilders. Two years later he moved to Houston and started Perry Homes.

“Perry told me that he built the business more conservatively than most people build a business,” says spokesman Holm. “He kept his risks very low and kept his equity-to-debt ratio very safe. Perry Homes has always grown in a measured fashion.” It was this fundamental conservatism that allowed Perry to survive the real estate, banking, and homebuilding cataclysm that took place in Texas in the eighties. Companies with any significant debt were wiped out. According to Raymond Palacios, who worked for Perry Homes from 1986 to 1996 and now owns a successful car dealership in El Paso, “Mr. Perry went through very hard times because the mid-eighties were very tough for the housing market. The business really took off with the building of master-planned communities. There was double-digit growth.” The company’s success was spurred in part by the fact that many homebuilders were, by that time, bankrupt, casualties of the real estate bust. Perry’s master-planned communities are now a common sight, especially around Texas’s major cities.

Perhaps because he has made his money off those who can afford to buy their own homes, a significant portion of Perry’s charitable giving has targeted those who cannot. Ten miles across the border from Brownsville, through the teeming, cluttered streets of the booming Mexican city of Matamoros, is a private orphanage called the Matamoros Children’s Home. Also known as Casa Hogar, the home houses 186 orphaned, abused, abandoned, or neglected children from ages four through eighteen. It is run by a doctor named Saul Camacho and his wife, Maria. Its principal benefactor is Bob Perry.

Casa Hogar is not the only orphanage Perry supports outside the United States. There are many more in Mexico, in Reynosa and elsewhere, that I was not invited to tour, or even informed of. He supports another in El Salvador that he does acknowledge. On a tour of Casa Hogar’s brand-new, Perry-donated dining hall in January, I saw a Christmas tree covered with cards the children had made thanking Mr. Perry, as he is known, for his kindness. Perry may be alternately admired, feared, or loathed in Texas political circles, but here, he is loved. He is a frequent visitor, and the kids all know him.

According to Perry’s friends, the lesson I should draw from my tour of the orphanage is this: While it is typical of his philanthropic work, it is also just a small sample of the activities in which he has long been involved. “He has dozens and dozens of these things going at a time,” says Michael Stevens, a Houston developer who chairs the Governor’s Business Council and is one of Perry’s closest friends. “I have never called him to do something for people that he has not done. His charitable giving is far larger than what you have seen in the political arena.” He does not even tell his friends the full scope of what he does, according to Weekley. “I consider Bob a good friend, and I had no knowledge of the orphanages,” he says.

By all accounts, Perry is extraordinarily, and spontaneously, generous in his giving. It is driven by what Holm terms “the multiplier effect, the idea that he can go and help someone who is a net drain on society and turn him into a net plus. It is a version of ‘Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.’ ” Though Stevens, like Perry, does not like to acknowledge his charitable gifts, he offers two examples of projects he and Perry have developed together. One aims to give jobs to soldiers who have lost limbs in the war in Iraq. Stevens says the two men have sunk “hundreds of thousands of dollars” into the project. “We plan to roll it out in six months,” he says. “The plan is to get corporations throughout the U.S. to employ injured veterans.” The other project is typical of what friends say is the more personal side of Perry’s giving. When former U. S. attorney Michael Shelby, a man Perry and Stevens admired greatly, died after a long struggle with cancer, the two men made sizable donations to a college scholarship fund for his children. “This kind of thing happens all of the time,” says Stevens. Indeed, one of Perry’s classmates from Meridian High School says that this sort of private, personal charity extends to his old hometown. “Over the years, any of the people we went to high school with who had money problems, he helped them,” says Hiram Woosley, who played in the backfield with Perry for the Meridian High Yellow Jackets.

The list goes on: $100,000 to the United Negro College Fund, $1 million for a YMCA in League City, more than $1 million to fund scholarships for the Center for Mexican American Studies at the University of Houston. “A lot of people are surprised to learn that we are friends,” says Tatcho Mindiola, the sociology professor who directs the center. “He knows that I am a liberal Democrat, and we have candid discussions and discuss our views. I discovered that he is a strong supporter of affirmative action, and that would surprise a lot of people in the Republican party. He knows that discrimination is real, and he thinks there should be special outreach to get Hispanics involved in education. He is not a rabid right-winger. Simply not.”

THOUGH HE NOW GIVES MASSIVELY to national campaigns, it was in his home state of Texas that the intensely private Perry first entered the brawling, public, intemperate world of politics. He was not always a Republican. Prior to 1978, he was a Democrat and gave money primarily to Democrats. That year he supported incumbent Dolph Briscoe in the Democratic primary for governor. Briscoe, a conservative Democrat, lost to the liberal John Hill. Republican candidate Bill Clements then called on Perry, who was already wealthy enough to appear on politicians’ radar screens. Clements laid out his pro-business, pro-jobs agenda and asked for Perry’s support. The result was that Perry ended up heading Democrats for Clements and co-chairing his winning campaign. Three years later fellow Houstonian James Baker, who was then White House chief of staff under Reagan and who knew Perry from the local political circuit, said to Perry, in effect, “You believe everything that we believe, or even more so. You should switch sides.” Baker converted him, and Perry was soon swept up in the Reagan revolution as a newly minted conservative Republican. (It is an interesting coincidence that 1978 was also the year Karl Rove went to work for Clements, launching a career that, like Perry’s, has been instrumental in transforming Texas from a Democratic to a Republican stronghold.)

Throughout the eighties and nineties, the political cause Perry was most passionate about was tort reform, the campaign to rein in huge, multimillion-dollar jury verdicts in favor of plaintiffs. Over the past 25 years, he could usually be counted on to support any candidate for the House or Senate who was opposed by either a trial lawyer or by someone funded by a trial lawyer. He has given millions to Texans for Lawsuit Reform. “He is a patriot, and as a patriot he believes that there are major public policy issues that are very important for the country, like tort reform,” says Weekley. “Without it, he thinks our civil justice system is not on solid ground. If people lose faith in the ability to get a fair trial, then it is a threat to our civil society, and he literally sees it that way.”

Perry’s money was hugely influential; when it moved, especially in a Republican primary, it was often the kiss of death for anyone opposing Perry’s candidate. It meant that, if you were going to run as a Republican and not put tort reform at the top of your agenda, you had better have independent wealth. Like James Leininger’s support for candidates who favored school vouchers, Perry’s money became a de facto enforcement mechanism for Republican candidates in the primaries. And, of course, inflows of such money meant that any Democrat who smelled remotely of “trial lawyer” invariably—through the efforts of Perry, Texans for Lawsuit Reform, and others—found himself in a race with a well-funded opponent.

One such case is particularly illustrative. In 2002 Perry gave $31,000 to Dionne Roberts, who opposed incumbent Democrat Scott Hochberg for the Texas House of Representatives. Shortly after this, Perry appeared at a United Negro College Fund gala dinner in honor of the late John Coleman, a prominent Houston physician and civic leader and the former chairman of the fund’s Houston chapter. Also present at the dinner was Coleman’s son, Democratic state representative Garnet Coleman, who had been bothered by Perry’s support of Roberts. “I went up to him and said, ‘I don’t understand why you spend your time and money going after someone like Scott Hochberg,’ ” Coleman told me. “ ‘He’s just trying to help schoolchildren get an education.’ ” According to Coleman, Perry responded by saying, “Well, he is supported by those trial lawyers.” To Coleman, this confirmed that Perry’s donations were made for purely ideological reasons. The problem, as he saw it, was that “Perry’s only reason for going after Scott was that Scott had gotten a check from the trial lawyers. He didn’t look to see whether Scott had value in the Legislature, and he didn’t look to see some of the things Scott had done that he might have agreed with … It is things like this that contribute to the clear partisan and ideological divide in the Legislature.”

Perry’s financial clout sometimes works in the Democrats’ favor. In 2004 Democratic representative Patrick Rose was thought to be facing a tough challenge from a Republican opponent. But when Perry signaled his support for the pro-tort reform Rose with gifts totaling $15,000, it virtually guaranteed Rose’s victory. Minority Democrats in particular have been the recipients of some of Perry’s largesse, a fact his critics often fail to mention. While his biggest contributions to individuals in 2006 went to Republican losers Joe Nixon ($262,500), Jim Landtroop ($100,000), and Michael Schofield ($100,000), he also dropped substantial amounts on minority candidates, including Democratic representatives Sylvester Turner ($50,000), Eddie Lucio III ($25,000), Ana Hernandez ($22,500), Norma Chavez ($20,000), and Senators Rodney Ellis ($17,500) and Mario Gallegos ($21,000).

It should be noted, though, that most of the minority Democrats in the statehouse who have received Perry’s money are supporters of Republican Speaker Tom Craddick. Perry, in fact, has repeatedly proved his willingness to use his money against Republicans who are deemed insufficiently supportive of the Speaker. You could see this sort of thing happening in 2006, when six incumbent Republican representatives were targeted for opposing Craddick or for being RINOs— Republican in name only. Perry gave $62,500 to Republican challenger Chris Hatley in his losing primary race against incumbent Charlie Geren; he gave $40,000 to Lorraine O’Donnell in her losing race against Pat Haggerty; and he gave $10,000 to Nathan Macias in his bitterly fought primary victory over incumbent Carter Casteel.

Much of this has had to do with pursuing his primary issue of tort reform, and as almost anyone in Texas will tell you, Perry and fellow travelers like Weekley have succeeded in curtailing litigation. Moderate reforms over the years culminated in major legislation in 2003 that severely limited the jury awards plaintiffs could win. Perry’s enormous giving during the elections of 2002, leading to the Republican sweep of the statehouse, in effect made that happen.

But Perry is by no means a single-issue donor. Land commissioner Patterson notes that back in 1984, when he was running for Congress, “Perry asked me, ‘What is your position on life?’ It kind of confused me at first. Then I realized he was talking about abortion. So I told him what I thought.” Some of Perry’s large-gift recipients in 2006 included the Republican Party of Texas ($780,000), Texans for Lawsuit Reform ($601,000), the Harris County Republican Party ($125,000), and Texans for Marriage ($100,000). They summarize his fundamental conservative Republican leanings: He is pro-tort reform, anti—gay marriage, and anti-abortion.

Perry wields some of his power in Texas through his relationship with the Austin lobbying firm Hillco Partners, one of his closest and most important affiliations and a firm closely aligned with Craddick. For roughly the past ten years, Perry’s lobbyist has been Neal “Buddy” Jones. Jones’s partner Bill Miller was until recently Perry’s spokesman and has now assumed the less visible role of adviser. Jones consults regularly with Perry both in his lobbying efforts for Perry Homes and as an adviser to Perry on legislative issues and on various candidates and races in Texas. Though no one knows exactly what Jones tells Perry, the implicit power in that advice is huge, having the potential to channel Perry’s resources into specific races. This of course means that Jones—already one of the most powerful lobbyists in Texas—has just that much more clout. Perry also gave $545,000 last year to Hillco’s political action committee, which amounts to Miller and Jones’s private piggy bank to dole out to legislators and candidates as they see fit. And though Hillco has full discretion on how the money is spent, it acts as a de facto conduit for Perry’s personal money.

Perhaps nowhere was Perry’s Texas clout more apparent than in the 2003 creation of the Texas Residential Construction Commission (TRCC). An offshoot of the tort reform movement, the TRCC was ostensibly intended to make it easier to resolve disputes between builders and homebuyers and to amend the old system that was notoriously builder friendly. The result, says a chorus of critics, was just the opposite. In practice the TRCC became a captive agency to the industry it was supposed to regulate, and the law forced consumers to go through a lengthy complaint process only to find that at the end, the TRCC had no power to compel builders to do anything. This outcome was, of course, entirely favorable to the homebuilding industry, and in fact, it turned out that the person who’d written most of the bill that had created the commission was Perry Homes’ corporate counsel John Krugh, who was later appointed by Governor Perry to the newly created TRCC.

As soon became known, Governor Perry had received a $100,000 contribution from Bob Perry roughly a month before signing the law and appointing Krugh. Bob Perry also spread money around to the two legislative committees that had worked on the legislation. Texas homebuilders in general had given $8.9 million to candidates for state office between 2001 and 2003. The inherent conflicts of interest touched off a large and ongoing controversy. In January 2006, Comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn issued a blistering report, saying, “After reviewing TRCC and its enabling statute, it is clear that the agency functions as a builder-protection agency … For these reasons, if it were up to me personally, I would blast this TRCC builder-protection agency off the bureaucratic books.” Many people came to believe that, in effect, Bob Perry had been given his own state agency. Says Janet Ahmad, of Homeowners for Better Building, a watchdog group and consistent Perry critic: “Perry was the kingpin and the brains behind the TRCC. He was always behind the scenes.”

AND THAT IS WHERE HE IS content to stay. Because he refuses to speak to reporters, it has never been possible to know what Perry himself actually thinks about his position as one of the most powerful and controversial private citizens in American politics. For the purposes of this article, however, he agreed to answer some questions through his spokesman, Holm. The arrangement was informal: I would give questions to Holm; Holm would relay them to Perry and take notes on the replies; then Holm would convey the answers back to me.

What does Perry think about the savaging he receives in the media? “He doesn’t dwell on it,” Holm said. “And he tends not to say negative things about people, though he thinks the media portrayals are not an accurate reflection of him. There is a real and negative impact on his family, however, who think these stories and portrayals are gross mischaracterizations of the man that he is—a benefactor of society and a caretaker of the underserved.”

I asked Holm to ask Perry to list the five issues that he cared the most about. Holm gave them in order of priority, as follows:

1) Jobs. “He’s very free market,” Holm explained. “He believes that job creations are the way to empower families.”

2) Education. “As you can see from his donations, he feels that education really is the great equalizer.”

3) Immigration. “Mr. Perry says we have to have immigration policies that give people hope. What is this nation other than a nation of hope? And we have hope because we have lots of jobs and educational opportunities.”

4) Security. “Perry is a big supporter of domestic security, from cops on the street through the war on terrorism.”

5) Tax reform. “He believes in tax relief, empowering the middle class and giving back to families.”

My first response to this list was surprise that tort reform was not on it. “That’s deliberate,” Holm said. “A few years ago it absolutely would have been.” My second response was that the agenda could easily be that of a Democrat. “Exactly,” Holm replied. “And of course, as you know, he funds lots of Democrats.”

I also wanted to know how Perry reconciled his obvious desire for privacy with his desire for political action. For the first time in our exchange, Holm put Perry’s response in the first person: “I don’t know that I desire absolute anonymity. I’m rather private and don’t have a need to go out there, but I am willing to make important sacrifices. Obviously I am because I give up substantial amounts of money, and I am also giving up my privacy. I do it because I think it is in the best interests of the cause, be it political or charitable. I just view it as a sacrifice.”

Whoever Bob Perry really is, such selflessness will no doubt be chilling news for his foes.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Bob Perry