Remember the bumper stickers that appeared in the early eighties, after the dream of $40 oil evaporated but before the reality of $15 oil made the bust too serious to joke about? “Oh, Lord, Please Send Us Another Oil Boom,” one version read. “We Promise Not To Screw It Up.”

Those prayers have been answered—and not because of Saddam Hussein. The new boom started months before Iraq invaded Kuwait, when a barrel of oil still sold for $20. It is no ordinary boom either: The brush country between San Antonio and Laredo is the hottest oil play in the world. In a single oil field more than ninety drilling rigs are probing the depths of the Austin chalk formation. That’s 9 percent of all the active rigs in the United States. Back roads that were deserted a year ago have become thoroughfares for rumbling tank trucks that carry off oil day and night. Southbound travelers on Interstate 35 most maneuver past convoys of mobile homes, which are in demand for everything from bunkhouses to temporary offices. At night the rural darkness is interrupted by vertical strands of fluorescent lights that climb out of the brush, illuminating rig sites where drilling continues around the clock. In Pearsall, the largest town in the region, with a population of seven thousand, bars now open at eight in the morning to oblige shift changes on the rigs. South of town, the rigs fan out in three directions, toward tiny towns with names that evoke the frenzied action swirling around them: Big Dilley, Divot, Derby.

What is remarkable about this boom is not just how big it is but how little the rest of Texas has noticed it. To be sure, a few newspapers have written about the new technology known as horizontal drilling that has made the boom possible, but the prevailing attitude outside the oil patch is skepticism. The boom is like a phone call from a lost and forgotten lover: not entirely welcome, a reminder of good times that turned sour, of the end of innocence, of harsh truths learned and years irretrievably gone, of how easy it is to make a terrible mistake and how foolish it is to think that things will last forever.

Texas has changed. We no longer believe that oil can save us. Even the word “boom” has come to carry an unsavory connotation —a hint of unreality, self-indulgence, and folly. Never mind the prayer on the bumper sticker, Lord; we have learned our lesson: Oil booms are short-lived, speculative, ruinous to those who rely on them. Send us high tech instead.

But before we scratch oil from Texas’ future altogether, we should take a closer look at what is going on in Pearsall and the oil field that bears its name. Is the new oil boom destined to repeat the mistakes of the last one? Or have the people swept up in the boom—oil-men and investors, drillers and rough-necks, suppliers and town merchants—learned their own lessons from the dreadful purgatory of the eighties? Is the cycle of boom-and-bust something that Texans should fear and avoid at all costs? Or should we accept that the rewards of the pursuit of oil—the greatest engine of instant social and economic mobility ever invented—are worth all the risks?

No Vacancy

The manager of the Texas Employment Commission office in Pearsall answered the telephone one day in early September and was surprised to hear an old man ask in a quavering voice for an oil-field job. He was calling from San Antonio, where he lived on Social Security, and he had heard about the Pearsall boom.

“Is there any way you can get me on somewhere?” the man asked. “I’ve worked every oil boom for the past fifty years. This may be my last.” As it happened, an oil company was looking for a gate guard—someone to live in a trailer 24 hours a day and make a list of everyone who drives into and out of a drilling site. The old man got the job.

The story of Texas oil is always told from the top, in books like The Super-Americans, by John Bainbridge. The Super-Americans is one of the best books ever written about Texas, and it captures, in a witty, raised-eyebrow way, how high-rolling wildcatters like Murchison and Hunt and Cullen and Richardson created the legend that Texas and Texans were larger than life. But by focusing on the oilmen, we have missed the real importance of oil to Texas. The oil patch produced a way of life among ordinary people that contributed more to the shaping of the Texas character than all the wealth and flashy lifestyles of the wildcatters. Oil brought opportunity and change—not just on the rigs but throughout the enormous support industry that accompanied the search for oil. Oil provided the social mobility that was missing in the factory or the corporate office. It spared Texas from becoming a class-conscious place where workers resented managers and managers looked down on workers; it kept alive the notion that a man had control of his own destiny.

This is the kind of change that occurs in an oil boomtown: A man drives up to the Security State Bank in Pearsall to make a deposit. He mentions to the teller that he is new in town and is looking for a secretary for his oil-field supply business. Does she know anyone willing to make good money by working twelve-hour days and weekends? Indeed she does. Camille Patton leaves the bank where she has worked for most of the past eleven years and joins the oil boom.

And this is what occurs in a boom-town: On the I-35 bypass, where Pearsall’s only commercial venture is an inn called the Porter House, bulldozers clear the ground for another motel. As soon as the first wing is finished—while construction work continues on the rest of the motel—oil-field workers move into every room. Today the completed Royal Inn has neither a restaurant nor a blade of grass on its grounds, but in its six months of existence, it has never had a weekday vacancy.

All this was beyond the imagination of anyone in Pearsall a little over a year ago, before the oil boom began. The town’s main thoroughfare was so deserted that, as a local banker put it, “You could have played football on Oak Street and never had to stop the game.” All but one of the buildings occupied during the last boom by oil-field service companies were empty. Weathered For Lease signs went unheeded. In a long, narrow field surrounded by a high fence, repossessed oil-field equipment awaited buyers who never came.

But Pearsall’s problems went beyond an ailing oil industry. To go there is to travel not just in distance but in time—back to an era when agriculture was the dominant industry in Texas, when Mexican Americans didn’t vote, when restaurants served only Tex-Mex and chicken-fried, and change occurred slowly, if at all. Although Pearsall is 70 percent Mexican (the political term “Hispanic” is seldom heard), it has none of the Spanish grace of other South Texas towns—no central square, no old church, no architectural features. Farmers and ranchers settled the area first, the Mexicans later—too late to affect the town’s dull physical character. With its agricultural sheds and railroad tracks close by the business district and its courthouse several blocks away, Pearsall looks oddly out of place in South Texas, as if it really belongs in the Panhandle.

Before the new oil boom began, the Pearsall economy was just peanuts—literally. Field workers typically earned less than $4 an hour. Outside of agriculture, the main sources of jobs were the government and retail sales. Oil was regarded as a thing of the past. You could get an oil lease for $50 an acre, but who would want one? Hardly any wells had been drilled in the Pearsall field since 1982; it was just about played out.

Then came the stunning announcement in September 1989 that Dallas-based Oryx Energy had successfully drilled a huge horizontal well in the Pearsall field. Moreover, Oryx was so sold on the new technology that it planned to drill up to 85 more wells in the region. The Oryx well had been such a “tight hole”—oil-field jargon for a well-kept secret—that Oryx had been able to lease 100,000 acres at bargain prices before letting the word out.

Instantly Pearsall was invaded by swarms of landmen, who pored over deed records so intently that the court-house stayed open on weekends to accommodate them. Leases for mineral rights soared to $250 an acre. Long-idle oil-field workers streamed into town looking for work. They came from oil towns all over South Texas—from Victoria, from Alice, from Laredo, from Carrizo Springs—and, as the word passed through the oil patch, from Kilgore, from Midland and Odessa, from Oklahoma and Louisiana, even from Canada. The lucky ones found places to rent; the unlucky ones slept under the Frio River bridge south of Pearsall. When the new arrivals crossed paths with longtime residents, the results could be amusing. A job-seeking rough-neck walked into the Texas Employment Commission office to undergo a required check for drug use while three prim and proper school workers were there filing unemployment claims. “I’m here to take a piss test,” he announced loudly, causing the flustered workers to inquire if they were expected to do the same.

In a small town, every variation from the usual pattern is news—and Pearsall was full of news. Even before the drilling started in earnest, some of the big landowners began showing up around town in new pickups. Conclusion: Oil companies were paying big cash bonuses for leases. In front of the empty oil-field service buildings on North Oak, weeds that had grown head-high over the years had been mowed to the ground. Before long, the For Lease signs came down and the buildings filled up. Bleecker Morse, the Lone Star beer distributor for five brush country counties, could track the oil boom with a barometer more accurate than the rig count: His sales were up 17 percent in towns near drilling activity but flat in towns where there was none. He noticed, too, that while he used to know everyone eating lunch at the Porter House, suddenly he knew no one.

Sales tax receipts were up, unemployment was down, Oryx had more than doubled the number of wells it planned to drill, from 85 to 200—but those weren’t the economic indicators that mattered to the people of Pearsall. They measured things in more personal ways. The local school system had tried for years to find a permanent speech therapist—to no avail. Then, last spring, Superintendent Patricia Santos found herself with three unsolicited applications, all from spouses of newly arrived oil workers. To Joel Garza, the owner of a small diesel-engine repair shop, the boom meant year-round demand for his services. When agriculture was Pearsall’s only industry, he worked on irrigation pumps in winter and waited through the long summer for cold weather to come again; now he had oil-field trucks to keep him busy. To Security State Bank president Also ‘Galloway, the proof of better days was not just that deposits were up 15 per-cent compared with the previous year, but that the apartments he owned were full at long last. He had built them during the last boom and soon wished he hadn’t; between booms the occupancy rate had lingered below 50 percent.

One damp evening in the early fall, Galloway went out for a jog on the high school track. Billowy clouds hung low over the city, blown in from the coast, and as Galloway looked out to the darkening east, he saw the cloud banks bathed in an eerie orange light. There must be a big fire on the edge of town, he thought to himself, but in the next instant he knew better: It was the re-flection of natural-gas flares burning on well sites so new that no pipeline had yet reached them. “It was,” Galloway recalled, “one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen.”

$16.66 a Minute

At the end of a bumpy dirt road lined with catclaw and prickly pear, the horizontal well known as Johnston No. 3 probed the earth for signs of oil. Somewhere underground, invisible and uncharted, lay the eastern boundary of the Pearsall oil field. Pearsall itself was fourteen miles to the west; if the oil-field boundary happened to be in that direction, the well would almost surely be a dry hole. If the line was to the east, the odds of finding oil were excellent.

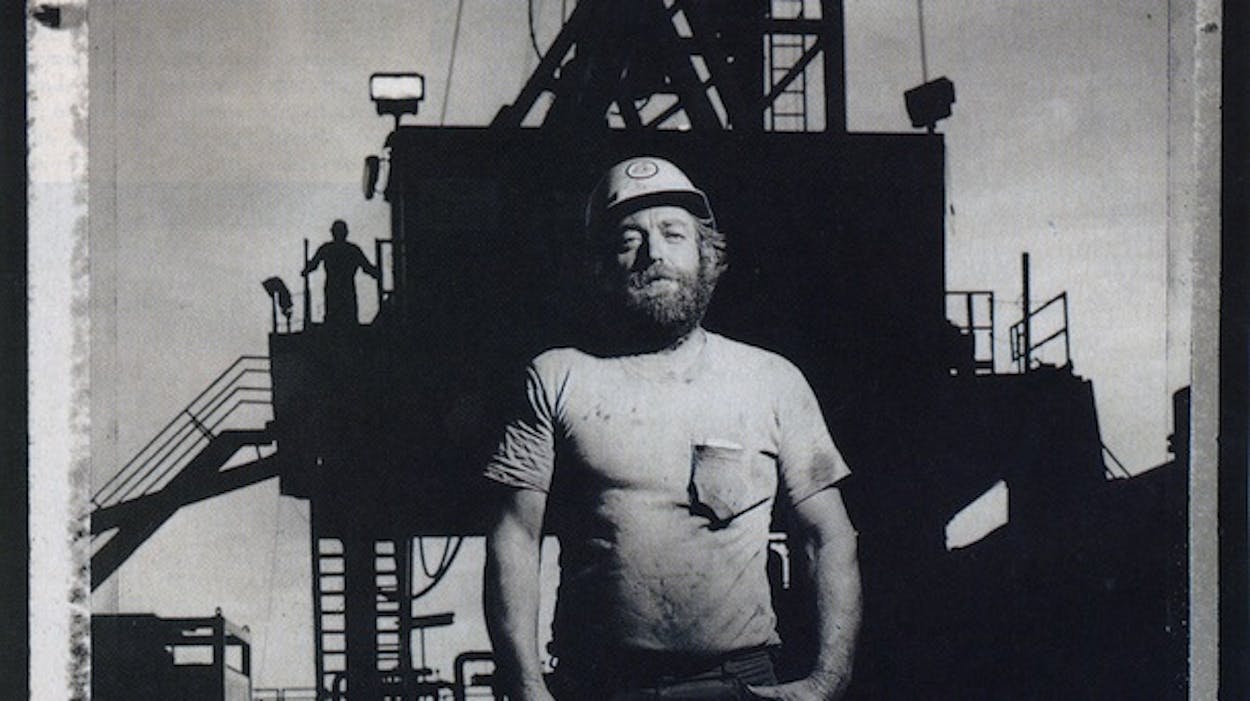

The drilling rig towered two hundred feet into the first cool air of autumn. On the rig floor, eighteen feet above the ground, the five-man drilling crew was adding a thirty-foot length of pipe to the string, which was already almost a mile long. The operation was surprisingly quiet. A steady hum issued from two generators a few yards east of the rig. When it was time to lift the pipe out of the hole, the sound of a motor kicked in, and a drum wound with a thick cable began to turn. The cable raised the 80,000 pounds of pipe just high enough so that the connection between the two highest pipes peeked above die rig floor. Two roughnecks wearing thick work boots and even thicker gloves moved in on the pipe. One attached a chain to hold the bottom pipe steady—if it rotated even slightly, all the pipes connected to it would rotate, and so would the drill bit a mile downhole; and if the drill bit rotated, the hole would veer off in a different direction, and heads would roll. As another roughneck separated the two pipes, steaming hot water gushed out of the top one and splashed onto the rig’s wooden floor. When the pipe was empty, die cable lifted it high enough to allow a new thirty.footer to be inserted. The string was reconnected and sent back into the depths. The operation had taken about four minutes.

“In my younger days we could do it in a minute less,” Johnny Russell said.

Russell was the on-site boss at Johnston No. 3. His business card identifies him as a consultant, but in the oil business everyone calls his position the company man. Oilmen don’t hover around rigs anymore; people like Russell supervise the drilling for them. The company man is like a general contractor. The oilman decides what land to lease, how much to spend, where to put the rig, which direction to drill, and how deep to go. It’s the company man’s job to see that the well gets drilled on line and on budget.

The four-minute pipe extension had cost close to $67, based on the going rate for drilling rigs. That may not sound like much, but $16.66 a minute works out to $24,000 a day. Drilling for oil can bring an astonishing amount of money into circulation in a short time. To drill a horizontal well in the Pearsall field takes about a month and costs anywhere from $700,000 to $1.2 million. If drilling stayed on schedule, the bill for this job would come close to $700,000. Some of the money would leave the area, of course, as profit and overhead for out-of-town companies and to buy specialized equipment not available in Pearsall, but much of it would stay in the region, to pay for staples, oil-field services, and salaries.

A large part of the company man’s job is deciding which oil-field service companies to use. Visits from sales managers based in Pearsall and Dilley consumed much of Russell’s days. He knew many of them from his seventeen years in the oil patch. “Oil is a worldwide industry but a small business,” Russell said. “You see the same people in different places, and you get a reputation.”

On this well alone, Russell hired roustabouts from a local construction company to clear the well site and pour cement. He hired horizontal-well consultants to track the drilling by computer and a mud logger to check soil samples for indications of oil, and then he had to rent used mobile homes for them to live in. He picked one of the local maid services spawned by the boom to clean the trailers. (“You can keep it clean but not like a woman does.”) He had to find a fuel supplier to keep the generators and the pumps running. He kept the phone number of a local welder handy. He set up an account at an oil-field supply house, known as the place to get “rope, soap, and dope [a pipe lubricant]”—and valves, seals, gloves, everything, in fact, from a complete rig to crockpots. And if the well came in, he would need an oil-field chemist to remove water produced with the oil, a vacuum truck to haul off the separated water, and, finally, a transportation company to buy the oil and truck it to a pipeline or a refinery.

Russell was in his late thirties, with a soft, round face and the slight extra girth that comes from too many years of eating bad food in faraway places. He had dark-blue eyes, but everything else was red: hair, moustache, jumpsuit, windbreaker. His home and family were in Nacogdoches, but during the drilling of Johnston No. 3, a well-side mobile trailer was his residence 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Inside, the main room was furnished with a lumpy sofa, four wooden chairs, a and breakfast table with a copy of Clear and Present Danger on top, and a desk with two phones and an ad. ding machine. The only wall hangings were a seismic chart of the drilling progress and a flyswatter. The vinyl floor, the upholstery, the curtains, and the paneling were brown. On the kitchen counter were a small television that displayed more snow than picture, a shortwave radio, and the most ubiquitous accessory in the oil patch—a pack of cigarettes. “I haven’t been home in two months,” Roo- sell said. “If they ever go to shootin’ over Iraq, Ill never get home.”

Growing up in Nacogdoches, Russell had imagined his future to be in ranching. “I bought me some cows when I was nineteen,” he said. “I only had ’em three months before the price hit bottom.” To feed his cows, Russell joined a cousin who worked on a rig. “I sold out as soon as the price went up. I’ve hated cows ever since.”

Oil was different from ranching. It wasn’t at the mercy of the weather or—so it seemed in those innocent days of 1973—of irresistible market forces. To Russell, the joy of working in the oil fields was that a man’s fate depended only on two things: “How much sense he has and how hard he works.” In five years he worked his way up to driller, the top position on a drilling crew. The rig count was in full thrust then, and company men were in short supply. Exxon hired him off the rigs, gave him a month of training, and sent him into the field as a company man making $30,000 a year. He was 24 years old.

In 1982, when the rig count began to fall, Russell left Exxon for Tenneco. Four years later he was supervising a well in New Mexico when the price of oil plunged to $10 a barrel. The bad news came over the telephone: “When you get through with this hole, shut her down and go to the house.” Russell decided to set up a consulting business as a company man for hire. He got enough jobs to see him through, one of which was a successful horizontal well in Oklahoma. When the Pearsall boom hit, he had experience in the technique.

The hour was approaching midnight: time for Russell to check on how the drilling was going. They were getting close now; at any moment the well could break into a fracture and find oil. Yet there was no feeling of anticipation or tension. Out here, in the deep South Texas night, the glamour of the oil boom and the charged boomtown atmosphere of Pearsall seemed to belong to another world. Up on the rig floor, the drilling crew went through its routine every thirty minutes—pull the pipe, add the pipe, lower the pipe. The crew had come to work at six that evening and would not get off until six the next morning, and then it would have to drive thirty minutes to Dilley, where the drilling company kept a group of mobile homes for bunkhouses. The other men at Johnston No. 3 (there were, of course, no women) were hidden away inside their trailers, watching the drilling progress on their computer screens and looking for anomalies that might indicate the presence of oil. The idea that one of the men might come running out of a door, screaming, “Oil! Oil!” like some modern-day Jett Rink was inconceivable. There was nothing to do now but wait. The fate of Johnston No. 3 lay with the Austin chalk.

Fantasy Land

The Austin chalk had a bad reputation in the oil patch: It’s a promoter’s dream but an operator’s nightmare. The chalk has enough oil to lure the greedy and the unwary, but it is hard to find and harder to get out. A lot of people went broke trying in the final throes of the last boom. The chalk is a layer of limestone about 200 feet thick and 7,500 feet below the earth’s surface. It runs east and north across Texas, from close to Eagle Pass all the way to Louisiana. In most oil fields, like those of the Permian Basin, the oil is saturated in porous rock. But in the chalk, the oil is isolated in networks of fractures and gaps where the limestone has cracked over the ages. These cracks run up and down, making the chalk a giant sideways oil field. Trying to drill into a crack with a standard vertical well is like trying to put a rose stem into a bud vase with a blindfold on. Horizontal drilling makes geometry work for the oilman—the hole is aimed at the broadest surface of the oil. That is like trying to put a rose stem into a window box.

No oilman was more suspicious of the chalk than Gale Galloway. The brother of Security State Bank president Alex Galloway, he grew up in Pearsall in the forties before going off to play football at Baylor. Later he headed oil companies in Houston and Austin. Now a Baylor regent, he still has the carriage of an athlete from the days when football players weren’t all bulk. Galloway has been involved in hundreds of oil wells, and he has seen booms come and go in the Pearsall field, but he has never looked for oil there before. He stayed out of the last boom because he didn’t like the odds. Back then a well cost $500,000 to drill, and even the successful ones depleted fast. For a well to be profitable, oil prices had to stay at $35 a barrel or go even higher. “I looked at those prices and decided, ‘This is a fantasy land,’ ” said Galloway. “That’s why we’re still in business.”

But Galloway no longer considers the chalk to be a fantasy land. His oil company, Austin-based GLG Energy, has 300,000 acres under lease, the most of any oil company operating in the field. He made his decision to get into the chalk in a big way when the price of oil was around $20 and showed no sign of going higher. Horizontal drilling made the economics of finding oil in the chalk so attractive that he couldn’t resist.

Horizontal drilling has three advantages over vertical drilling:

(1) More oil. Once a horizontal well has penetrated an oil-bearing crack, it can keep right on going to the next one, and the next; in effect, it is several oil wells for the price of one. A few prolific wells have produced more than a thousand barrels a day. At $20 a barrel, that adds up to $140,000 a week.

(2) Faster payout. A horizontal well starts to produce oil from the first crack it encounters, even as it continues to bore through the chalk in search of more oil. A big well will pay off half of the rig costs during the drilling.

(3) Higher success rate. In a temperamental field like the chalk, horizontal drilling turns a risky venture into a sound one. GLG Energy had drilled 30 horizontal wells in the Pearsall field as of mid-October. Most were near old, depleted vertical wells, but some were, in Galloway’s words, “trying to widen the fairways” of the oil field. The result: 29 successful wells.

During the last boom in the Austin chalk, a typical vertical well produced a disappointing 30,000 to 50,000 barrels over its lifetime. Even at the unsustainable price of $35 a barrel, that represent-ed an income of $1 million to $1.75 million for the oilman. Subtract expenses—for drilling, royalties to the landowner, severance taxes, well-servicing fees, overhead—and for good wells the profit might be half a million. Marginal wells could be saved only by higher prices.

The new boom is the real thing. The best estimates are that the average horizontal well will ultimately produce 150,000 to 250,000 barrels. Oryx expects its wells to average 400,000 barrels. At $20 a barrel, that’s $3 million to $8 million a well—and at least a $1 million profit after expenses. And that was the margin before the price of oil shot up briefly to $40. For the first time since the 1973 OPEC embargo, the success of Texas oil production—in the Pearsall field, at least —does not require the rest of the country to suffer high prices for our benefit.

Taking advantage of horizontal drilling, however, requires money, and money has been all too scarce in Texas since the last boom ended. Galloway was able to move into the chalk quickly because he had access to capital; an insurance company that had backed GLG in an earlier drilling program was willing to take a substantial piece of his action in the chalk. That he was from Pearsall was an additional selling point: He still had a ranch near town, he knew the local landowners, they banked with his brother, he had a good shot at getting prime leases from ranchers who would trust his word that he would drill on their land soon. That was how things worked out. His first success in the chalk, the Beever No. 1, was drilled on a lease from one of the I biggest landowners in the area. “Folks know where my barn is,” Galloway liked to say. “They can burn it down.”

As the news of the play in the chalk spread, it turned out that capital wasn’t so scarce after all. Wall Street investment funds are getting into the chalk now, and so is money from England and Australia. And as long as there are oil booms, there will be promoters offering deals. Galloway recently fielded an advice-seeking call from a corporate executive who had been solicited to invest in a well touted as the Dilley Monster. A lot has changed in the oil patch in the past ten years, but one thing will never change: Money follows opportunity.

Once Burned, Twice Shy

For the people of Pearsall, opportunity is a mixed blessing. The new oil boom has brought money to town and newcomers to spend it and jobs to spread it around. “It’s wonnnderful,” said Alice Pate at the Texas Employment Commission, practically singing the first syllable. “I used to look into faces that had no hope. Now look at my desk”—it was covered with requests for bulldozer operators, roughnecks, waitresses, and more. “It’s wonnnderful.” The Porter House has added fifteen employees. Many of the retail businesses have hired an extra employee or two. But that is as far as folks in Pearsall are willing to go. What you won’t find in this boomtown are new buildings, new residences, new restaurants, new businesses (except for the Royal Inn), even new additions to old businesses—in short, any capital investment greater than paving a parking lot. This town is taking no chances. Pearsall will take the money and put it safely in the bank.

Once burned, twice shy: The memory of what happened in the last boom, when opportunity proved to be the road to ruin, is still all too fresh. The Ben Franklin store expanded, but then came the collapse, Wal-Mart, and the end of the Ben Franklin. Everybody who could scrape together a little money bought a rent house, but then the tenants went away, and as recently as a year ago, 245 dwellings in Pearsall were empty. Workers borrowed money to buy low-cost housing, only to lose them to Federal Housing Administration foreclosures when the work ran out.

Bob Valadez remembered how the last boom had almost ruined him. Now the owner of the Pizz-A-Ghetti ($3.10 for a poorboy, $4 for a lasagna plate), Valadez had left a relative’s Italian restaurant in San Antonio to work for Western Company, an oil-field service outfit, in 1980. He was one of two people hired out of the two hundred people who showed up at the Hilton in downtown San Antonio to interview with Western for oil-field jobs. “They liked me because I’d been working sixty to seventy hours a week in the restaurant,” Valadez recalled. Western taught him to handle the high-pressure equipment used to increase production of old wells. “I saw a whole well get blown into the air once,” he said. “It was spinning around like a lasso.”

Valadez started in Alice at $5 an hour, but after two years he was up to $8.75 plus twenty hours of overtime a week—more than $30,000 a year. He accumulated fifteen credit cards. But then the boom collapsed, and there was less and less business for Western. Valadez saw co-workers quit and their positions go unfilled. He saw colleagues with the least seniority get laid off. By this time Valadez had been transferred to Pearsall, and he knew that his days were numbered. He destroyed his credit cards while he still had a job and paid off the balances. When Western finally laid him off, on April 1, 1986, he was debt-free. He put up his gray-and-white Blazer as collateral for a $6,600 bank loan and bought a pizza oven and other used restaurant equipment. He and his wife rented a shell on Oak Street, put in walls, counters, and plumbing themselves, and opened the Pizz-A-Ghetti in June of that year. It was the only restaurant in town other than the Porter House that wasn’t Tex-Mex

Business was slow. “For a long time it was just money circulating.” Valadez said. “The people from the filling station across the street would come over and eat; I’d go over there and buy gas.” But then the landmen came to town and the oil workers followed, and soon the townspeople had more money to spend on eating out. Valadez’s sales went up 20 percent in two years, even though the restaurant was no longer open on Sundays.

Last spring Western asked Valadez to come back to the oil business. The company was returning to Pearsall. Did he want a job? But the time for taking those kinds of risks had passed. Instead he rented some more space, added a few tables, and waited for the oil boom to come to him.

Like Bob Valadez, Pearsall’s merchants are not ready to plunge into the boom. “I learned last time, don’t run that inventory up,” said Howell Arnold, the president of ABC Hardware. When the old boom ended, his shelves were full, but his sales were cut almost in half. Despite the influx of people with money in their pockets, merchants aren’t spending more on advertising. “In the last boom, I had no rejections on sales calls,” said Chuy Sifuentes, the owner of the local radio station. “Now people are very guarded with their money.” Most measures of econom-ic confidence—the price of raw land, the demand for bank loans, the number of building permits—are flat. The boom has brought more jobs but not necessarily higher wages. One mechanic who works on oil-field trucks shrugged indifferently when asked about the boom. “The work is dirtier, but the pay’s the same,” he said. “I liked it better the old way. At least we had some spare time.”

The townsfolk aren’t the only ones with long memories. Oil people also are more prudent. The service-company employees who were transferred to Pearsall in the last boom usually bought houses; this time, they rent. Many have not even moved their families to town. Offices are spartan. Larry Haschke, who hired Camille Patton out of the drive-in bank window, supplies rigs with fuel out of a portable building so small that three desks and their chairs occupy all the floor space beyond the doorway. At Enron’s oil-transportation office, the waiting area consists of a black vinyl sofa, a four-foot square of red carpet that looks more like a sample than a rug, and a battered chair permanently occupied by a paper cutter. In the last boom an oilman and even an oil hand might leave a $20 tip for a pretty waitress at the Porter House. Now, said Isabel Mufioz, as she refilled coffee cups around a table, weekend hunters leave bigger tips than oil regulars.

West of the Tracks

The Missouri-Pacific Main Line runs north and south through the middle of Pearsall, formalizing the division that is the primary fact of life in South Texas. East of the tracks, Pearsall is mostly middle class and Anglo. West of the tracks, Pearsall is mostly poor and Mexican. Here you can still see chickens walking in the streets, wash hanging on backyard clotheslines, and old men walking stooped over from a lifetime of labor in the peanut fields. Only three main streets cross the boundary to link the two sides of town. Back in the thirties, when there were still “No Mexicans Allowed” signs in local restaurants, Mexican kids who tried to cross the tracks to go to high school were driven back by Anglo youths brandishing rocks and bricks. Until the late sixties only two streets were paved on the west side. One was Peach, a small commercial artery lined with shops—groceries, restaurants, cantinas, junk stores, shoe repair stores, washaterias. Now all but a few are closed. A mural of the Virgin in pink robes on a gold background looks out over a shuttered grocery. Above the entrance to a crumbling brick and stucco building with barred windows, a faded and chipped sign identifies the long-abandoned headquarters of the Raza Unida party.

One has to search long and hard here for visible evidence of the oil boom. Traffic is unaffected. In the past year two small neighborhood businesses, a bar and a cafe, have opened on Peach Street. A few houses—very few—have new pickups out front. At the Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic Church, Father Joseph Reyna has noticed new faces at mass, and despite the recent deaths of a few generous contributors, donations are stable. But for the most part, this neighborhood of small frame houses is where the trickle-down benefits of the oil boom run dry.

Just as Pearsall is divided by the railroad tracks, the west side of town is divided by an invisible line separating workers who have skills from those who don’t. Few people from west of the tracks work on the rigs. Roughnecking requires skills that can be learned only from experience, but so many experienced hands have descended upon Pearsall looking for work that there is little opportunity for rookies. The main source of jobs for Mexicans is driving oil-field trucks, but here too companies are looking for people who already know how to do the work. Since the boom started, Enron has tripled its fleet of tank trucks from ten to more than thirty and its roster of drivers from twelve to sixty; more than 85 per-cent of its work force is Mexican. Drivers earn between $24,000 and $40,000 a year —a lot of money in the brush country. But Enron hires only drivers with two years of eighteen-wheel experience. Many of its new employees are veterans of the old boom who had been laid off. For those who qualify, the boom is a god-send, a way to stay home with their families instead of driving cross-country or to quadruple what they were earning as house painters or mechanics in Pearsall’s moribund preboom economy. But for those who can’t drive a truck or repair engines, the boom might as well be in Kansas. No one moves from the peanut fields to the oil fields.

Women in an oil boom fare worse than men do, and the poorer they are, the worse they fare. The jobs created by the boom—maids, waitresses, secretaries, teachers—don’t pay as well as truck driving or roughnecking, and the better ones require skills that are in short supply in Pearsall. Of the 27 new teachers hired this year to cope with the 10 percent increase in enrollment, only 4 were from Pearsall, and 2 of them were members of the landowning Beever family. The west side abounds with single mothers. On some Sundays they account for half the baptisms at Father Reyna’s church. These young mothers can’t afford to go to work; they must stay on welfare to get free health care for their children. If anything, the oil boom has made life worse for the poor. With the increased demand for apartments, rents have almost doubled. People who couldn’t afford the increase have had to vacate and move in with relatives. “I hear Use poor people say, ‘Oil boom—so what?'” Father Reyna said. “‘All it means to us is higher prices.'”

Traces of Oil

Johnny Russell was not a happy man. Another day of drilling had gone by, and the Johnston No. 3 had bored through the Austin chalk, found a crack in the limestone, and struck . . . water. The water contained traces of oil: enough to turn the liquid black but not enough to make it any more viscous than ink. The water, which is heavier than oil, would have to be pumped away before the well could start to produce. At the moment, though, it wasn’t pumping anything. For four hours the rig had been shut down while everyone waited for a welder to come and fix a piece of equipment that kept slipping. “You didn’t see a welder up the road lookin’ lost, did you?” Russell asked. He had already called the welder three times, and with the rig’s meter running at $1,000 an hour, he called again. “Ol’ Bob didn’t come back to the house, did he? Jes’ checkin’. He’s bound to be somewhar.” When Russell was agitated, his East Texas accent thickened.

“This is typical,” he complained as he hung up. “It’s not who you want to use, it’s who you can get. Vacuum trucks are never available. I’ve had to shut down a thousand-dollar-an-hour well for a fifty-dollar-an-hour truck.

“It’s the same way on the rigs. You don’t have the quality of people you used to, the pride. The older people got laid off and don’t want to come back, and you don’t see new people wanting to go to work in an oil field. Younger people just aren’t attracted to it.”

Finally the welder showed up, and the Johnston No. 3 went back to pumping out the unwanted water. If the well is like others nearby, it will eventually produce between three hundred and four hundred barrels of oil (and up to seven hundred of barrels of water) a day—not a big well by the standards of the horizontal-drilling boom, but big enough. Even if the price of oil was $20 a barrel, the well would bring in at least $2 million in a year.

By early November the rig and trailers were gone from Johnston No. 3, replaced by a pumpjack and storage tanks. Russell had joined forces with another company man, Terry Garrett, and opened an office in Pearsall. He would start on another well in December, and he was already talking about doing one in Gonzales and maybe eight more after that. There was no reason why Pearsall should be the only place where horizontal drilling worked; there was all of the Austin chalk to be drilled, all of Texas, a play in Alabama. California looked good. People were coming to Pearsall to learn about horizontal drilling from as far away as Singapore.

Once, Texans made the mistake of thinking that there would never be another bust. Then we thought that there would never be another boom. That too was wrong. Now the pattern of extremes has begun anew in Pearsall, and we must somehow come to terms with our cyclical destiny. Perhaps the county clerk in Pearsall gave us the epigram for the new boom when she explained her feelings to the local newspaper. “I tried to be pessimistic,” she said, “but I just can’t.”