This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

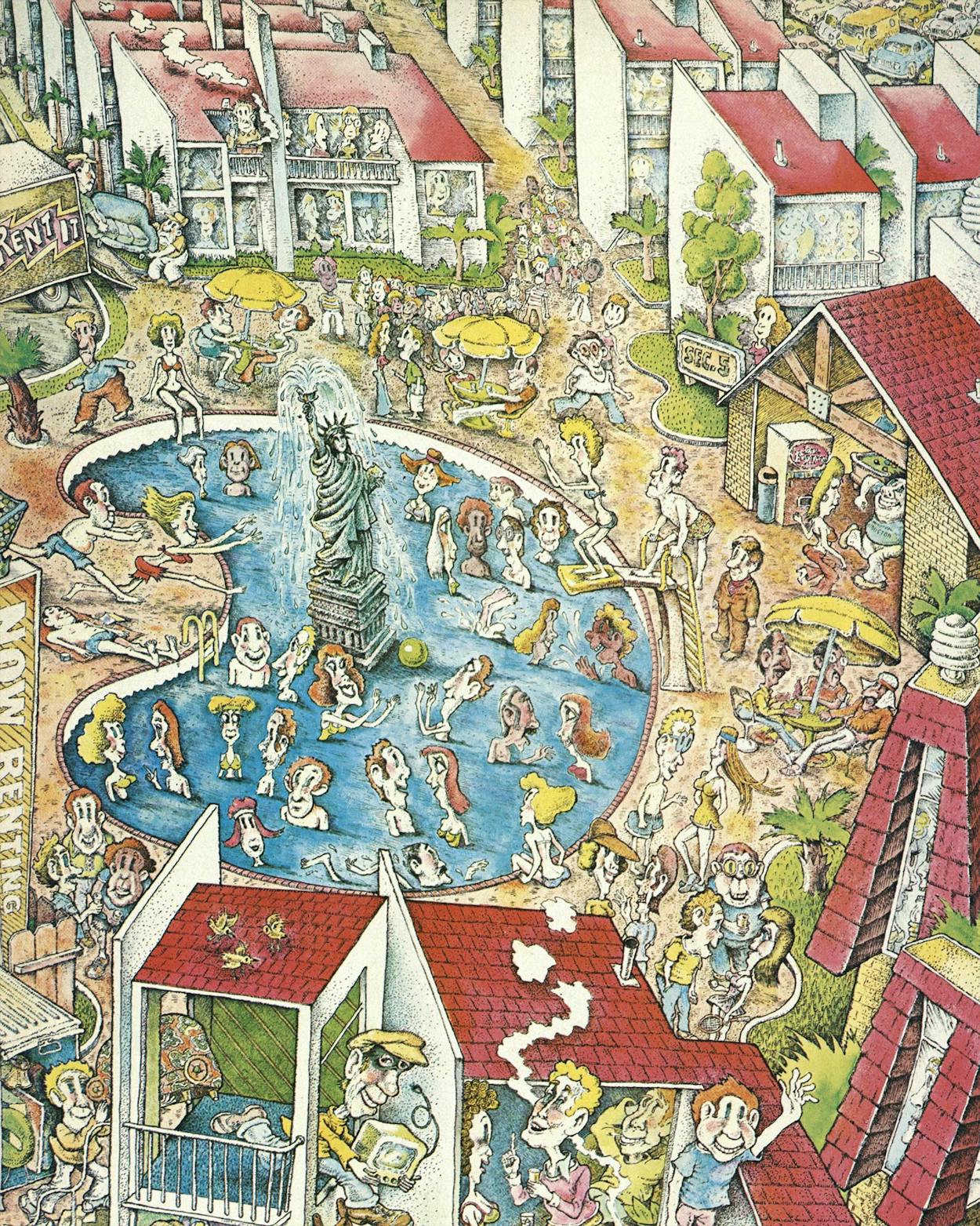

I felt like an immigrant entering New York Harbor the day I drove out to Southwest Houston and spotted the darkened silhouette of a businessman holding a roll of blueprints. The silhouette stood at one end of a plastic sign near the entrance to the Napoleon Square apartment complex. Next to the outline of the little man, the sign read, “Harold Farb Investments Rental Office.” For most of my life as a native Houstonian, I had recognized that silhouette as the logo of the nation’s largest independent landlord and apartment builder. Now, as I prepared to begin my new life as an apartment dweller, I realized that it was also Houston’s equivalent of the Statue of Liberty, the beacon that directs the masses of new urban immigrants to the apartment complex melting pots of the Sunbelt.

A few minutes after entering the rental office, I found myself riding across Napoleon Square’s oceanic parking lot in a white golf buggy. The driver of the cart was a well-scrubbed young woman who politely asked permission to call me by my first name. “My name’s Impala,” she said, “just like the car.”

As Impala maneuvered the golf cart over the speed bumps in the asphalt, I marveled at the rows of apartments rising up around us like canyon walls. The architecture was an unremarkable combination of brick facades, iron balconies, wood fenced patios, imitation mansard roofs, and nonfunctional white chimneys euphemistically advertised as “New Orleans French.” But what astounded me was the sheer size of the place. The section blocks of apartments went on acre after acre, divided only by the bisecting driveways of the parking lot. At the very center of this sea of apartments, on an ellipse at the intersection of all the main driveways, there was a small building with a brick facade and large windows decorated with hanging plants. Behind the building, there was a forty-foot swimming pool surrounded by an iron fence with brick posts.

“We have over eighteen hundred units here at Napoleon Square,” Impala said, pointing to the pool and the small building. “We have twelve smaller pools in addition to our main pool, which you see here, and we have our club, Bonaparte’s Retreat.”

Impala stopped the golf buggy in front of section 26, a replica of all the others, and showed me two one-bedroom apartments, one upstairs, the other down. Both units had avocado-green nylon shag carpeting with matching appliances and identical floor plans: living room, kitchenette, bedroom, bath, and walk-in closet. Like Harold Farb’s plastic silhouette, nearly everything in the apartments could have been refined and synthesized from a few barrels of oil. The rent was $215 per month.

“The only difference between the apartments is that the upstairs has a balcony and the downstairs has a patio,” Impala advised. “I’d recommend the upstairs if you want a view and the downstairs if you want privacy.”

Since the vastness of the complex made me feel a little uneasy, I told Impala I would prefer the downstairs apartment. We got back in the golf cart and returned to the rental office, where I filled out a series of application forms, which were embossed with the Harold Farb silhouette. A few days later, my application was approved. Equipped with an apartment key, a mailbox key, a parking sticker also embossed with the Harold Farb silhouette, and some personal belongings, I moved out of the Houston home where I was born and into Napoleon Square’s section 26, apartment 1051.

I soon discovered that most of the myths about apartment life—the fast and sexy lifestyle, the anonymity, the predominance of automobiles over people—are true. But I also discovered that Napoleon Square is playing a very important role in one of the most significant social movements of our time: the great relocation of America. Hoping to escape familiar big-city plagues like crime, crowding, corruption, poverty, and poor housing, people from older cities have joined rural Americans and the new waves of immigrants from other countries in a rush to the cities of the sunny southern latitudes—cities like Houston, Dallas, Phoenix, and Atlanta—where unemployment is low and opportunity abounds. Although a few of these new immigrants are trying to escape political repression, just like those who earlier left the Old World for the New, the majority have come in search of a better material life.

Houston has become home for more of these new urban immigrants than any other city. For several years now, the generally accepted figure on net in-migration has been over a thousand people per week, and that rather astonishing number does not include the great masses of undocumented aliens who have been flowing in from the South even as out-of-staters and rural Texans have been charging in from every other direction.

Forming patterns much like the age rings in the trunk of a great oak tree, Houston’s people have settled in ever-widening concentric circles, with most of the city’s earlier residents living closest to downtown, usually inside Loop 610, and most of the city’s more recent arrivals living outside the Loop. Native Houstonians and other Inner-Loopers like me are a minority. The majority of Houston’s population is now composed of Outer-Loopers, people who have moved into town from somewhere else.

Throughout the South giant apartment complexes like Napoleon Square are often the places where these newcomers go first. In Dallas, most of the large projects are clustered between Northwest Highway and Loop 635 east of the North Central Expressway. In San Antonio, the apartment complex quarter is mostly north of Loop 410 near the University of Texas campus. In Houston, there are now major apartment developments in every quadrant of the city, but the largest concentrations by far are in Southwest Houston. In fact, nearly 60 per cent of all new apartment complexes built between 1970 and 1977 were built in Southwest Houston.

Napoleon Square is one of the oldest and most populated apartment projects. Located just beyond Loop 610 where the Southwest Freeway crooks toward Sharpstown, the Napoleon Square area was nothing but a patch of prairie across from the Bellaire Skating Rink until the middle sixties. Today Napoleon Square sits amid one of the largest concentrations of “garden-style” apartments anywhere in the world. Within a one-mile radius of its front gates, there are no less than 5000 apartment units in at least twenty separate complexes, two dozen or more nightclubs and bars, a dozen tennis courts, and over forty full-size swimming pools. Bounded by railroad tracks on the north and busy commercial thoroughfares on the other three sides, Napoleon Square and the other complexes around it have developed into a special, self-contained neighborhood, a sort of world of their own.

The character of that world has undergone considerable change in the last few years. Once the reigning capital of Houston’s swinging singles scene, it is now populated by a rainbow of newcomers, most of whom have less splashy lifestyles but much more varied origins than the young professionals, or “young pros,” of the “swingles” days. In addition to tenants from New York, California, the South, and Midwest, the big complexes play host to considerable contingents of Iranians, Jordanians, Saudis, Lebanese, Mexicans, South Americans, Japanese, Vietnamese, and East and West Europeans. As one resident transplanted from Chicago put it, “There’s not a native Houstonian within seven thousand feet.”

The product of all this is a combination of crowding, crime, and cross-cultural diversity that in some ways resembles the immigrant ghettos of old New York—melting pot neighborhoods like Orchard Street and Hester Street. But the true character of the Napoleon Square neighborhood is unique to the new cities of the Sunbelt. This curious land of apartment complexes is neither a sinkhole of impoverished immigrants nor a high-powered Swinglesville. It is instead a here-today-gone-tomorrow-land where people mingle more than meld and permanent friendships tend to last at least a week. It is at once a very easy and a very uneasy place to be, a pocket in plastic land that has become one of the first stops on the new interstate highway to the old American dream. It is also a phenomenon in need of a name. Not long after I saw Harold Farb’s darkened silhouette on the rental office sign, I came to think of the place as “Minglesville.”

Imoved into Minglesville on a white-hot Houston afternoon. Approaching from Westpark Drive on the north, I turned my car up the embankment of the railroad tracks, twisted around the end of the perpetually malfunctioning barricade arms, and bounced down the southside slope, barely missing a baby-blue cement mixer headed across the railroad tracks in the opposite direction.

I quickly saw that I had entered an archetypal world developed without zoning laws. The cement mixer had come from the nearby Lone Star Industries on Renwick. A few yards beyond the tower of the cement company was a little strip of pastureland where two brown mares were grazing. Next to the pasture was a long line of brick-facade apartments, then a light-metals yard and the Men’s Wearhouse warehouse and office, then nothing but more and more apartments until the road narrowed to the vanishing point. Out front, there were signs bearing such names as The Pepper Tree, Confederacy, and Gulfton Gardens.

On the east side of the road, between four of the larger complexes, was a shopping center with tenants whose names have become household words in Houston: Taco Bell, Stop ’n Go, Eckerd Drug, Pilgrim Cleaners, Weingartens. There was also a “healthy foods” restaurant, an ice cream and frozen yogurt shop, a pizza joint, a submarine sandwich shop, an apartment-locater service with the easy-to-remember telephone number 661-RENT on a roll-away sign out front, a game room and billiard parlor, and an assortment of “neighborhood” bars with names like the Ragtime Club and the Magic Forest. Scattered among all this were one or two horseback riding rings and an occasional patch of land overtaken by weeds.

Despite the heat, I was grateful for a sunny day. All the roads leading in and out of the neighborhood were narrow and rutted, drained only by old-fashioned open ditches. I could just imagine that during one of Houston’s late-spring or early-summer monsoons, the entire area would become a swimming pool of sewage, snakes, and trash.

The first person I met inside Napoleon Square was a short, blonde woman in a green shirt, white slacks, and cork-heeled shoes. I met her, naturally enough, by taking a wrong turn at the main pool and ending up in the wrong section of apartments. I went to the door of her apartment thinking it was the unit I was supposed to occupy.

“That’s okay,” she said in a squeaky voice as she peered at me from her doorway. “I’ve made a lot of mistakes like that myself. I’m from Lubbock, and I’ve only been in Houston a year—I mean, a week.”

She pointed me in what she thought was the right direction, and I set out looking for my own apartment again. After I found it, I returned to thank her for her help, but she was not there. I went back several more times over the following week, but I never saw her again. Then I learned from one of her neighbors that she had lost her job and moved out.

Later, I discovered that some tenants had actually lived in Napoleon Square for three or four years. A few had even lived there since it opened, nearly eight years ago. But according to the management, the average occupancy is about one year. Calculating quickly, I figured that upwards of 10,000 different people had passed in and out of Napoleon Square during the life of the project.

I spent the first night in my apartment sleeping on the floor. The next morning, I was awakened from my nylon shag slumber by the knock of the men from Modern Furniture Rentals. In what seemed like less than sixty seconds, the two well-practiced movers brought in a sofa, armchair, coffee table, nightstand, two lamps, and a mattress, box springs, and bed frame. All of a sudden my unfurnished one bedroom was furnished. Like the apartment itself, just about everything was made out of ultradurable plastic. The sofa and armchair were a thread-checkered Herculon. (“You can stick pins or nails or just about anything into that stuff, and it won’t rip,” the guy at the rental outlet had told me.) The coffee table and nightstand were made of “high-pressure Melamite,” a laminated plastic Westinghouse has trademarked as Micarta. (“Resists scuffs, alcohol, boiling water, cosmetics, moderate heat, and stains,” the label promised.) I had acquired all these fine appointments for the amazingly low price of $29 per month. Plus a $25 delivery fee. Plus a $25 security deposit attached to a three-month lease. That made my total cash outlay $79.

As I stretched out for the first time on my indestructible Herculon sofa, I pondered the list of rules I had been given along with my lease. According to management policy, I could not have a motorcycle, a boat, a pet, or a child. Had I moved in a few months earlier, I could have had a boat, but the boat pen, which was located right outside my front door, had become too crowded, so they were now prohibited also. I learned that I could not hammer nails in the walls, wash my car in the parking lot, bring glassware around the swimming pools, or expect to be paid damages if my apartment was destroyed by fire or explosion.

When the telephone installers arrived later that morning, I also learned that my phone could be installed in one of only two outlets, because the management had removed the moldings to prevent the apartments from being webbed-over with extension wires. Faced with the choice of purchasing an extension cord from the phone company or rearranging my furniture so the phone would reach the table, I elected to rearrange the furniture.

For the first several days of my stay at Napoleon Square, I thought the place might not really be inhabited by people—just cars. The occupant of the apartment above mine was a 1972 Dodge Charger, olive green with a white vinyl top and a CB antenna. Like most of the other cars in the parking lot, the Charger left early in the morning and returned late in the afternoon. But somehow I never was on hand to observe the actual comings and goings. A couple of times when the Charger was parked in front of my door, I heard rumbles and music up above, but when I went upstairs and knocked, no one ever came to the door.

I had about the same initial luck in meeting the other tenants in the complex. Although the basic architectural lines of Napoleon Square’s driveways and parking lots resembled the old cart-and-stall immigrant streets of New York’s Lower East Side, there was nothing that resembled street life. I heard the babble of foreign tongues frequently enough in the parking lot, but the scenes were only fragmentary: discussions of a flat tire, a bed that had to be moved in, an engagement that would be kept later on.

From my observations of the parking lot, I concluded that Napoleon Square was like a giant animal that slept all day and came to life only at night. In the evenings, the parking lot would be jammed with cars, and the patios and balconies would glow with yellow porch lights. I rarely saw many people wandering about, but I knew they were in there, somewhere. By sunrise, the cars would begin trickling out. Although there was never any mass rush for the freeways—no collective “Ladies and gentlemen, start your engines”—by eight or nine o’clock, the parking lot would be virtually empty.

The only activities during the day were the puttering of the workmen in their golf course maintenance vehicles and the slow laboring of the gardeners tending the plants in the courtyards and around the parking lots. (For all its obvious deficiencies, Napoleon Square was very clean and well serviced: the driveways were usually spotless, the flower beds neat, the walls were not delapidated, the place was, as I would hear so many tenants say, “pretty nice.”) As the day went on, however, bodies would begin to appear around the swimming pool, and the cars would begin to come trickling back in. By late afternoon, I would see a few people on the balconies, joggers in the driveways, Frisbee throwers in the parking lot. Then, night would fall, and Napoleon Square would again come aglow with yellow lights.

For all this ebb and flow, people seldom seemed to tarry long enough to meet each other. Consequently, by the time my first Sunday at Napoleon Square rolled around, the only person in the complex I knew by name was Impala, the girl at the rental office who had showed me in. Appropriately, she was named after a car.

That afternoon I decided I might meet my neighbors around one of the swimming pools. About a dozen people were sitting around the pool in the interior courtyard across from mine: some white girls in bikinis, a black man and a white man with athletic builds, a skinny Arab, and an Oriental woman in a flowered kimono. The scene looked at first glance like a parody of the American melting pot. Absolutely no one, however, was talking to anyone else. A few read magazines. Occasionally someone would jump in the pool. But mostly, the people just sat or lay there soaking up the sun as if there were no one on the planet but them.

The pool in the next section was totally different. Like characters out of an updated Elvis Presley movie, another dozen young people in cutoffs and bikinis and wild beach shirts were laughing and drinking and blowing grass. From one of the upstairs apartments a stereo boomed “Disco Inferno” by the Trammps. As I came into the courtyard, they quickly cupped their joints, sized me up, then resumed smoking. I noticed there were no blacks or Arabs in this crowd, just white kids with medium-long hair and mainstream middle-class faces. A volleyball net was stretched over the pool, secured by impressive concrete bases engraved with good American names like Chip and Art. This looked more like the popular image of a groovy apartment complex, but somehow I felt like an intruder. I decided to move on to the main pool.

This pool was a strange synthesis of the small ones. At one end some Arabs sat in the sun. A few feet away three young women lay on beach towels talking and listening to a transistor radio. Some men threw Frisbees, others swam, and some smoked dope. An older man sat in the shade and watched. I settled down on a reclining chair and soon learned that the three women on the beach towels were waitresses who worked the evening shift at a bar. They were all complaining about how late they got off work. The two Frisbee throwers kept trying to start a conversation with them. Their strategy was to float the Frisbee “accidentally” in the direction of the waitresses, miss catching it, attempt some humorous remark, and try again. The waitresses’ response was to appear uninterested, cool. Everybody around the pool seemed to be aware of what was going on and interested to see the outcome. Finally the two Frisbee players gave up their game and sat down on some chairs near the waitresses. The women talked to them for a while, then got up and left.

The conversations to my left were more poignant. Two white girls in see-through bikinis and a long-haired white boy in jeans were sitting around a table with a black fellow in a khaki safari suit and a flop hat pulled down to his ears. Every now and again, the girls would lean forward and snort cocaine off the extra-long nail of the black guy’s index finger. The two girls kept talking about sex.

“I can see two women makin’ it,” one of the girls said, “but I can’t see two guys. Women are tender and loving, and that’s what makin’ it is all about. With guys, it would be all uh-uh-uh.”

“I’ve only made it with a woman twice, and I was drunk both times,” said the other girl. “I had to be.”

“Well, I don’t want to hear about the first time,” cracked the black guy. “Tell me about the second time.”

A short time later, the two fellows and one of the girls drove away, and I struck up a conversation with the other girl. She told me that she didn’t live in the apartment complex but in a house nearby.

“I wish I lived here, though,” she said.

“Why’s that?” I asked.

“Guys,” she answered succinctly. “There’s always lots of guys around here.”

I asked her where she worked, and she said she was still in school—high school. “I’m fifteen right now,” she told me, “but I’ll be sixteen in six weeks.” With that, she got up from her towel, gathered her things, and rode away on a bicycle.

Not long afterward, I met my first foreigners, a couple of Iranian students named Dara Sepehr and Hassan Oamd. Dara was lean and wore a bikini bathing suit that increased his very European air. Hassan was heavier, with a darker complexion and a beard. Both were in their late twenties. Like most foreign students I met, Hassan said he had heard about Napoleon Square from a friend in Iran who had a friend who lived in the complex. He had no idea who might have been the original friend’s friend’s friend who first discovered the place for his countrymen. In any case, he and a couple of others had spent their first few nights in the U.S. sleeping on the floor of their friend’s friend’s apartment. Then, he and a friend had leased a two-bedroom place of their own. A civil engineering student at San Jacinto College, Hassan said he preferred driving 35 minutes on the freeways every morning and afternoon over living amid Pasadena’s chemical stench.

“It’s not bad here, I like it,” Hassan said. “In the morning, I go to school. In the afternoon I exercise at the spa in Sharpstown or sit by the pool. They are raising our rent from two-seventy to three-fifty, though, so I may go to another place.”

I mentioned that I had noticed a fairly large number of Iranians at Napoleon Square, but that they seemed to be scattered in small groups throughout the complex rather than huddled together in enclaves of Little Persias.

“One of the biggest problems for a foreign student is getting to college and back,” Hassan explained. “You’ve got to have someone to give you a ride. The best person to do that is another Persian. We try to live as close together as we can, but because the apartments rent out so fast, you have to take what you can get.”

Dara, who was visiting from England where he was attending school, complained that he had found it difficult to meet people, especially female people, at Napoleon Square. He also broached the subject of xenophobia. “All this propaganda about ‘the foreigners are coming, the foreigners are coming,’ is kind of funny,” he said, obviously meaning that it was not funny at all. “At school, they call Middle East people camel jockeys. But that’s nothing to be ashamed of. A camel is a nice thing to ride. You don’t have them.”

But while complaining of prejudice, Dara did not exactly aspire to the role of peacemaker for the Middle East. In fact, he seemed to have carried his own biases in the same bag as his toothbrush.

“We Persians stick together,” he asserted. “We don’t communicate with Arabs.”

During the next several days, I met quite a few more Middle Easterners, most of them Saudis, Lebanese, or Jordanians. Each group had a chapter and verse on all the other groups. The typical line was that the Saudis are rich but stupid; the Lebanese are stuck on themselves; the Jordanians are naive; the Iranians are too political, always picking arguments. Though most everyone expressed interest in meeting Americans, no one seemed to care for meeting students from other Middle Eastern countries. “I can see all the Persians I want when I’m at school,” said an Arab I met.

Thus, while being one of the most integrated neighborhoods in Houston with its rainbow of human kinds and colors, Napoleon Square seemed to be one of the most factionalized, hardly a melting pot. I soon discovered that prejudice was widespread among the people who maintained the apartment complexes in the Napoleon Square neighborhood. Although I never saw any evidence myself, I heard many complaints about Arab students who cooked meals in the sink or built fires on the carpet in the middle of the living room. “I just dread going into one of their apartments,” moaned a janitor at one nearby complex. “They never, ever clean up in there. The stink is just unbelievable.”

Shortly after my conversation with the two Iranians, I finally met the occupant of the apartment above mine. He was not a Dodge Charger but a young man named Dale Stowe, who came from Garden Grove, California. Dale’s father was a cop, his uncle was a cop, and his grandfather was a cop. But, as Dale himself put it, he liked to do some things every now and then that cops just aren’t supposed to do, so he had come to Texas on an adventure of his own.

The adventure had begun one afternoon when Dale and a buddy were sitting around Garden Grove out of work, drinking beer, doing nothing. More or less out of the blue, the two of them decided to take off for Houston.

Once here, Dale found a place to stay with his buddy’s uncle and started working for a building contractor. Pretty soon, he had enough money to buy the 1972 Dodge Charger with the CB radio. A short time after that, he came to Napoleon Square in search of his own apartment. A stocky kid with high, knobby cheekbones, Dale was only nineteen, a year too young to be a renter under the apartment complex rules, but he managed to get in anyway.

Dale began to drop by my apartment regularly when he got home from work. We would drink a few beers or scope out the parking lot with a surveyor’s transit Dale used at his construction job. One day he introduced me to his girl friend, who he said was the daughter of his boss.

“The other day, my boss asked me what I was going to do with my life,” Dale told me. “I said, ‘My life? I don’t know.’ Before he asked me about it, I’d never given it much thought.” He added that he still wasn’t sure what path he would eventually follow, but for the time being, his future would be in Houston.

The next person I met was a young woman from Lubbock. Our introduction came while she was in the process of washing the white interior of her Camaro in one of the parking stalls by my front door. She told me her name was Judy Weaver and that she lived in an apartment around the corner from my section. She had migrated to Houston via Dallas, where she had lived in another singles-oriented apartment complex.

“I’ve met a lot of people since I moved in here, but there aren’t really any group activities,” she declared. “Back in Dallas, we had a party at one of the complexes every weekend. I thought there would be more planned parties here, too.”

Judy said she had settled on Napoleon Square after looking at other complexes because the rent was cheap and it was close to her work. A clerk in a printing company, she had found a better job here than the one in Dallas. I figured she probably made somewhat less than the $12,000 annual income that was the estimated average for occupants at Napoleon Square.

“You figured right,” she said.

Like most of the other tenants, Judy sought her entertainment outside the complex. Her favorite spot was a country-and-Western place. Other people I met later had tastes ranging from the pretentious pickup clubs like Ciao to less exclusive discos like Genesis, classy topless joints like the Déjà Vu, cutesy-chic restaurants like Chili’s, billiard parlors on the Westheimer strip, and quiet little bars in the Montrose area. I discovered, however, that “goin’ clubbin’,” once the undisputed national pastime in apartment complexes, is clearly past its peak.

One night, as Judy and many of the other Napoleon Square tenants departed for the evening, I stuck around Bonaparte’s Retreat as people from other complexes began to trickle in. The crowd was mostly in the 18-to-24 age group and fairly heterogeneous. There were Mexican American guys from the North Side in inexpensive three-piece suits or Nik-Nik shirts and platform shoes, sweet-faced but not-quite-sorority-material girls in neatly pressed slacks, and lots of young people with long hair and wearing blue jeans. This latter group of kids weren’t sixties-era hippies—they were neither as colorful nor as scruffy nor as political—but they weren’t “young pros” or John Travolta types either. Most of them were just working people who liked to dance, smoke dope, dress as they pleased, and have a “good time.”

Bonaparte’s Retreat did its best to accommodate them. That particular Saturday night two cops were at the door checking IDs, but there was no cover charge and only a minimal dress code: “No cutoffs or shorts. No thongs or body shirts. No T-shirts or hats. No torn or frayed clothing. ID required.” Inside, the decor consisted of dim flickering gaslights, low brick arches, and plastic-topped brown tables, which combined to give the place a dank, constricted feeling. Bonaparte’s, like most of the other clubs in the area, doesn’t have live entertainment, but it does supply the four standard attractions—a bar, a disco dance floor, pool tables, and plenty of electronic games and pinball machines.

The crowd at Bonaparte’s that Saturday night was fairly sizable, maybe a couple of hundred during the course of the evening. But I later discovered that on weeknights the place is dead. Roberto Arranya, the assistant manager, claimed that the weekend business was enough to pay the overhead, but he admitted with obvious frustration that his ultimate boss Harold Farb did not seem very interested in taking the effort to increase business. As a consequence, poor Roberto, who proudly recalled serving the likes of Sonny and Cher in his days as a waiter at much fancier, bygone discotheques like Boccaccio 2000, had resigned himself to the job of serving faceless hordes of postadolescent apartment dwellers.

The hottest club in the Napoleon Square neighborhood turned out to be the Orchard Club at the Orchard apartment complex. The crowd was much the same as at Bonaparte’s but larger and populated by a few more fancy dressers. The dance floor was bigger and the interior less claustrophobic. That night the weekly dance contest was won by a couple who had moved to Houston from New York City. The male member of the duo was tall and skinny and looked just like John Travolta except for the additional feature of a thin, black mustache. His name was Ray Vitrano, but he went by “Vito,” and, much to my surprise, he could dance far better than the star of Saturday Night Fever.

“That movie kind of made me mad,” he said, after his victory in the dance contest. “Now everybody comes up to me and says, ‘You look like John Travolta, you comb your hair like John Travolta.’ Hell, I’ve been lookin’ like this for years.”

When I left the Orchard to return home, I suddenly experienced the cumulative effect of all the coming and going around the apartment complexes. The bumpy roads were bursting with Firebird Trans Ams and Z-28 Camaros, Cutlasses, Monte Carlos, Grand Prixs, Toyotas, Volkswagens, black Scottsdale pickups with luminous stripes, fancy vans with acid-trip-at-sunrise scenes painted on the sides, Skylarks, Gremlins, Matadors, Monarchs, Mustangs, Honda Civics, and Vegas. Wrecker trucks circled the area like vultures hoping to swoop down to clean up a mess made by the demolition-derby driving or tow away an illegally parked car. Meanwhile, light-blue apartment security sedans and Houston police cars cruised in and out of the parking lots, streets, and driveways.

The uneasy feeling I had felt since moving into Napoleon Square only intensified when I called the Houston Police Department to get the crime statistics behind the Saturday night scene. Last year Police District 18, which encompasses much of the heart of Southwest Houston, was second only to the predominantly poor North Side in total number of reported crimes. The type and character of those crimes is most revealing. Of the twenty police districts, Southwest Houston ranked only thirteenth in murder, but it was first in suicide and fraud; second in burglary, vandalism, theft, and auto theft; fourth in rape; fifth in robbery; and eighth in narcotics and drug-related arrests.

The Napoleon Square neighborhood suffers its fair share of the Southwest Houston scourge. The recently apprehended “Blade” rapist, who police blame for as many as fifty reported rapes, struck no less than six times in the immediate area of Napoleon Square. Before the “Blade,” the neighborhood terror was the infamous “Beer Belly” rapist. Since the capture of the “Beer Belly” and the “Blade,” the new menace is the so-called “Jumper Cable” rapist, who lures his victims by feigning car trouble. Many present and former residents complain of thefts and burglaries ranging from a missing TV set or prized leather jacket to the disappearance of a car. “Everyone who lives out there gets broken into,” says one former resident with only slight exaggeration. Cocaine and Quaaludes appear to be common in the complexes, and LSD seems to be on the way back, as is the case elsewhere. Heroin is also found in the area occasionally, though not as frequently as in some other parts of town.

A good portion of the crime in the Napoleon Square area is no doubt a function of the size and structure of the large projects. With their high density and architectural sameness, they are prime targets for criminals. Instead of just one victim, they offer many. Instead of the myriad of lock styles and floor plans found in ordinary residential neighborhoods, they share virtually the same design unit to unit, window to window, door to door. A method of breaking in that works on one apartment will often work on others. Criminals can find easy cover in the constant traffic flow of resident and nonresident transients.

The uniformity of the complexes, coupled with the superficially sensational Southwest Houston lifestyle, must also contribute to the area’s high suicide rate. Just wandering about the mazelike corridors and courtyards of my large apartment complex on a lonely, unsatisfactory afternoon or contemplating the unrelenting whiteness of my apartment walls, I found it easy enough to attain the state of pure dread and sufficient inspiration to invent fifty ways to leave my life. To my dismay I learned that most of those who finally do kill themselves are men.

As summer approached, I also became acutely aware of another apartment-complex hazard—fire. While I was staying at Napoleon Square, a blaze swept through the Trafalgar Square apartments on Briarhurst in Southwest Houston, causing an estimated $10 million damage and leaving at least seventy tenants homeless. The Houston Apartment Association does not keep statistics on losses by fire, but a spokesman told me that landlords typically lose 1 per cent of their units per year to the combined evils of fire and vandalism. The danger lies largely in the fact that all the units in a particular section often share the same roof, which is usually wood-shingled. As one fire department official put it, when one apartment goes, they all go. So far this year, Farb’s projects have been spared.

Apart from all these perils, I soon concluded that life in a Napoleon Square apartment had several other serious drawbacks. My toilet overflowed three times in a single day, even though I never fed it anything stronger than ordinary toilet tissue. The disposal thundered and growled so loud the time I tested it that I feared using it ever after. No matter when I took a shower—during peak hours in the early morning and evening or during off hours in the middle of the day—the hot water never came out properly; I was either scalded by a seething spray or frozen by an icy drip. And the walls were so thin that I could hear nearly everything that went on in the apartment adjacent to mine.

The only feature that consistently gave me pleasure was the dimmer switch for the overhead light in the living room. As I passed my days at Napoleon Square, I became expert in the use of the dimmer switch as a mood-control device. I would start with the light on full, so that it looked hard and white and round like a full moon, then I would turn it down to mid-range, so that it made the room just right for late-night talk. Later I would ease it down lower still, so that it was nothing but a faint orange glow.

It was after I had experienced several such dimmer-switch evenings and many, many mornings and afternoons by the swimming pools that I decided it was time for me to meet the maker of all I observed around me, the man whose darkened silhouette I had seen everywhere, the owner and operator, Harold Farb.

I found his headquarters tucked away in Braeswood Square shopping center, a few minutes south of the Napoleon Square complex. The door was not emblazoned with the ubiquitous silhouette or even with a name. Farb’s office was in an inner hallway and not even partitioned from the rest of the headquarters. Once past the reception area, I walked right in.

Harold Farb turned out to be nothing like his silhouette. Instead of a tall, dark, commanding figure, he is a light-complexioned 55-year-old man with an average build and a sensitive, slightly naive face. With him at the conference table was his property manager, Flo Sawyer, a pleasant but somewhat imposing woman who tried to do as much of the talking as she could.

Struck by the contrast between the figure on the billboard and the businessman I saw before me, I could not help but begin by asking Farb how he had arrived at his logo.

“Oh, that,” he said softly, “was something the advertising people thought up. They felt it would show people that there really is a Harold Farb.”

The real Harold Farb then proceeded to explain that his boyhood ambition was to be a big-band singer, not an apartment magnate. He discovered, however, that he could not support himself on the strength of his voice alone. In the early fifties, he turned to his father, Albert Farb, a successful commercial real estate operator, who got him started in the apartment-building business. Young Harold’s first project was a twenty-unit complex at 1811 Richmond in the Montrose area. Today he operates forty projects, all of them in Houston and most of them in the Southwest section, with a total of 12,000 units and an estimated 20,000 occupants, making him landlord to more people than live in the city of Bellaire. Some of the large management corporations own and operate considerably more apartment units, but the next-largest individual builder-operator is only half as big as Harold Farb. One knowledgeable real estate source estimated that Farb’s net yearly income could well be in the neighborhood of $3 million. Farb declined to reveal the exact profits or worth of his empire, but he did show me two very demonstrative signs of his success. One was a computer printout for the day showing that of the 12,000 units he owned, only 66 were vacant. The other was a record album, produced by his wife and titled Farb Sings Jolson.

“The economy here has been so strong that it’s been hard to make a mistake,” Farb explained.

Farb’s competitors can only cringe when they hear understatement like that. For Harold Farb’s relatively steady success in the face of the well-publicized booms and busts of the volatile Houston apartment market is an often discussed mystery to his envious fellow builders. During the halcyon days of the sixties, local developers expanded mightily to meet a mighty demand. But even as the market continued to absorb new units at the astounding rate of 15,000 per year, builders began cranking out apartments at a rate of 20,000 a year. In 1973 and 1974, the bubble burst, and a number of large developers, most notably John Jamail, who was then second to Farb, plunged into bankruptcy. An acknowledged outsider to the operations of the other large builders, Farb seemed to emerge from the crash virtually unscathed.

One of the reasons may be his marketing strategy. Instead of costly amenities, big promotions, and highly screened tenants, Farb’s approach has been low price and high volume. In the early days, he distinguished himself as the only large operator offering a no-lease, no-deposit rental agreement. Later, when market conditions changed and tenants wanted leases to protect against rent increases, Farb obliged with low-deposit, short-term lease arrangements. Through all the turns of the market, his occupancy rates remained among the highest in the city.

Napoleon Square has always been something of a problem for Farb. He built his $22 million complex in 1971, complete with a $400,000 disco and plenty of swimming pools, but Farb didn’t waste money on tennis courts or fancy promotional schemes. He simply offered brand-new apartments at prices lower than those in the surrounding area. His was not so much a “swinging singles” concept as a somewhat more conservative “single adults” idea. However, the superficial look of Napoleon Square was very similar to that of other complexes in the area, which were catering to young professionals. Soon Napoleon Square was also filled with young “pros,” and its club, Bonaparte’s Retreat, became the hottest spot in Southwest Houston.

Before long, however, the character of the apartment complexes began to change. When the Houston apartment market became glutted in 1974, a price war set in; new apartments offered many amenities for relatively low rent. Faced with the prospect of severe occupancy problems, local landlords could no longer pick and choose their tenants. Soon, the rising young professionals were replaced by newly arrived middle-class and working-class kids, many without college degrees, and by foreign students here to get degrees and go back home. As fancier and fancier private clubs and discos opened, the clubs at the apartment complexes began to decline, and Swinglesville suddenly became Minglesville, one of Houston’s most popular transient and immigrant enclaves.

This transformation was something Harold Farb had not counted on and one which he is already trying to reverse. In the meantime, he must cope with the demographic facts in his daily computer printout. During our interview, Farb and Mrs. Sawyer did their best to put a smiling face on the present state of life at Napoleon Square. But they also admitted to a number of serious problems involving both the place and the people who live there, especially the immigrants from abroad.

“It’s a touchy subject,” Flo Sawyer admitted. “We try not to discriminate.”

As my interview with Farb progressed, I began to test my own impressions of Napoleon Square with the remarks of the immigrants I had met. I realized that for most of the city’s newcomers, life at a large apartment complex—even one less attractive than Napoleon Square—probably is better than life wherever they came from. After all, I thought, when all the potential dangers and petty difficulties are put aside, how can a dingy one-room Manhattan apartment with poor heat, no idea of air conditioning, a pull-chain toilet, and rent in excess of $300 a month compare with a newly built one-bedroom Southwest Houston apartment with modern fixtures and appliances, central heat and air, easy access to swimming pools and tennis courts, rent under $250 a month, and a well-functioning dimmer switch?

I recalled the answer I had received from Howard Stokes, a young restaurant contractor who had lived in one of the complexes in the Napoleon Square area after moving to Houston from New York.

“There’s just no comparison,” Stokes had said flatly. “In New York, everybody’s more crowded than they are in one of the big complexes down here, but the family structure is still intact up there. I grew up in the same building with three hundred and fifty other families, but everyone knew everyone else’s name and what they did. The same people had been living there for years. There was a sense of roots even though it was all apartments. Down here everyone is so mobile. There aren’t many families in these complexes. Everyone is the same age. There’s no stability—physical or emotional.”

Howard added that he did not mean to imply he liked New York better than Houston. “You can do all the same things back there that you can here but it’s just a lot harder because you have to deal with that whole structure first,” he said. “There’s plenty of opportunity, but it’s so hard to make it happen that it’s effectively not there at all. Down here, it’s still possible to take advantage of your opportunities.”

Ironically, the one thing shared by most of the urban immigrants I met was a fear that Houston is becoming more and more like the decrepit cities many of them have recently abandoned. Some say Houston will be another Los Angeles. Others say Houston will be another New York. But the signs they point to are the same: more cars, more crime, closer-built housing, more large buildings, higher prices.

As a native Houstonian I noticed several subtler signs of this Manhattanization of Houston about which I felt good, bad, and ambivalent. The once popular 2K’s Ice Cream Parlor, scene of more first dates in Houston than there are on a hundred years of calendars, has been remodeled and renamed the New York Deli. The New York Times, once more rare than the endangered Houston toad, is now sold at newsstands all over the city. There is not just one or two but many Chinese restaurants, groceries that sell Vietnamese food, and Utotems that carry Syrian bread. There are large numbers of people who answer the telephone with voices much faster and harsher than homegrown ears can comfortably follow. There are many more things to do and see, but with all the people it always takes much longer to do and see them.

Another sign of the same phenomenon is the fact that more and more people are moving into apartment complexes like Napoleon Square. In 1970 roughly one-fifth of the population of Harris County lived in what is termed “multifamily housing.” Today, the figure is nearly one-third—higher if the estimated 12,000 to 14,000 apartment units that have been converted into condominiums are also counted. Meanwhile, apartment builders are back in action like never before. Having recovered from the overbuilding of the early seventies, they cranked out some 22,000 new units last year and have slated an estimated 25,000 more for completion this year. Bankers now show signs of tightening credit to keep the pace from getting out of hand again, but if present trends continue without another decline, over half the population of Houston will be living in apartments by 1990. By the year 2060, the entire city will be apartment complexes.

Perhaps the most regrettable implication of this trend toward apartment living is its effect on families with children. Although Farb and others do have family sections in some of their projects, most landlords clearly prefer to run the lower maintenance, less problematical “adults only” complexes. Most of the apartment projects that do accept children are being built in the outer sections of the city where there is less density and cheaper land. In effect, children are being zoned out of the central city.

So are new homes and in some areas old homes. As inner-city land prices have skyrocketed, town houses have gone up everywhere, with four- and five-unit minicomplexes often taking the space once occupied by a single grand old home. The trend toward condominium conversions is not only a part of this process but also a potential source of obsolescence for multifamily dwellings. The apartments now being sold as condominiums are in their first generation of ownership. The big question for the owners and developers is whether they will maintain a high resale value, that is, whether they can be turned over to a second generation of owners. If not, there will be a lot of bankers and condominium owners stuck with a lot of outworn apartments that nobody wants.

Somewhat to my surprise, I discovered that these developments do not particularly please Harold Farb. “If the trend continues, it’s the end of the American dream,” he told me, adding that despite his apparent economic interest in the growth of apartment living, he hoped the trend would halt or even reverse. “I’d just as soon taper off and build less,” he said. “I’ve done my thing already, and I don’t really have any great plans for the future.”

Cautiously predicting that the demand for multifamily housing will eventually level off, Farb went on to say that he does not think Houston will become another New York or another Los Angeles.

“Houston is going to turn out to be something completely different,” he said. “Not only do we have a vital downtown, which Los Angeles does not have, we also have a number of other major centers located at different points around the city—the Medical Center area to the south, the FM 1960 area to the north, the Katy Freeway–Highway 6 area to the west, and tremendous new development in the northwest. Houston is going to have a look all its own. Houston is going to be Houston.”

Farb claimed he did not plan to follow the trend of converting apartments to condominiums. Instead, he was developing a new approach to his future projects. “Our goal is to try to make apartments more like homes,” he said. “We are going to install fireplaces in some of our newer projects and we are toying with the idea of tennis courts.”

For all our discussion of Napoleon Square, I never felt that Farb had a sense of what he had wrought by his developments in the area. He conceded that he would do some things differently if he were to build the project over again (“I don’t think I’d build a club, for example”), but blamed most of the area’s problems on the absence of zoning laws, a remarkable complaint for a Houston builder. “We would prefer to be farther apart from the other complexes,” he said, “but we just don’t have any control.” Meanwhile, Mrs. Sawyer continued to downplay or deny many of the problems that exist at Napoleon Square now and to bubble optimism about the project’s future.

“We are constantly upgrading the facilities,” Mrs. Sawyer informed me. “As the tenants move out, we are replacing the old carpeting with a new grade that is finer than what you see in most expensive homes. Our hope is to attract more young professionals to the area, and I think we’re having some success. I’ve noticed that a lot more young people around there are dressing up in coats and ties.”

Farb added that his plans are to hold on to Napoleon Square and to continue operating it as an apartment complex for many years to come. “The one thing that area has going for it is location, location, location,” he said, paraphrasing an old real estate axiom. “When the city finally gets around to fixing those streets, which they say they are going to do very soon, that will be one of the prime areas in Houston.”

I’m not sure exactly what Farb means by prime, but Napoleon Square would have to become the Taj Mahal before I would want to live there again. Nothing really bad happened to me during my stay at the complex, but I would dream up any excuse I could to get away from the place, even if it was just for a few minutes. Unlike some other places I’ve lived—both apartments and houses—there was no center of strength, no spot in my one-bedroom or anywhere else in the complex that felt like a home. Instead, I was continually distracted by the creeping unease I had begun to feel almost from the moment I first spotted Harold Farb’s darkened silhouette on the rental office sign.

That same strange feeling followed me around for several days after I moved out of Napoleon Square. I saw, or thought I saw, Harold Farb’s silhouette everywhere I went. But now Farb was not merely on the signs. He was coming after me. And he was always just over my shoulder. Finally, in a moment of combined inspiration and relief, I thought to remove the parking sticker embossed with Farb’s silhouette from the rear window of my car.

A Tale of Two Apartments

Houston’s Singlesville then and now.

Sin Alley

The cluster of apartment projects around Midlane and San Felipe streets, just across the railroad tracks from exclusive River Oaks, was Houston’s first singles-oriented apartment community, a distinction that earned it the name “Sin Alley.” From the early fifties to the middle sixties it was a favorite playground for college kids and young and not-so-young professionals, all rather mild sinners by today’s standards. Then, this first generation of tenants moved out to the newer, nicer complexes outside Loop 610, and the area began to decline into a neighborhood full of crime, drugs, decadence, and despair. Last year, however, a partnership headed by 32-year-old Steven J. Rudy purchased 417 units in the area with the aim of renovating the old structures to a new glory.

Renamed St. Regis Place, Rudy’s Sin Alley resurrection may be the first large-scale project of its kind anywhere in the Sunbelt. Rudy’s basic idea is to apply the same concepts he has used for the last five years in restoring and remodeling old houses in the Montrose area. This time, however, his Creative Restoration Company will have invested about $3 to $5 million in property acquisition and another $5 million on improvements by the time the project is completed.

“That sounds like a lot of money,” Rudy said with a wry smile. “And it is. It took a lot of courage for lending institutions to back me because this kind of thing had never been done before.”

A native Houstonian, Rudy has no illusions about the history and former atmosphere of his pet project. “When we purchased the property, we found that we had our fair share of prostitutes,” he said. “We even had a gambling casino that the police had raided several times. Most of the tenants were low-income whites, Chicanos, and Orientals. But we also looked at the area as a prime location inside Loop 610.”

Instead of merely evicting and relocating all the tenants he inherited, Rudy claimed he has put 65 or 70 of them to work on his restoration crew. “Most of these people are unskilled laborers, but we are training them to be carpenters, brick masons, and concrete refinishers.”

The plan is to subdivide the eight projects into about twenty different complexes with no more than 50 units each. So far, he has completed Lafayette Square (50 units), La Petite Chateau (8 units), and Riviere Roche (23 units). He says he has rented each apartment almost as soon as it has become available, despite the fact that he has yet to do any advertising.

“People who used to live here twenty years ago are coming back,” he said. “They just see what’s happening when they drive by and stop in to check it out.”

Although he is keeping many of the floor plans intact, Rudy’s improvements involve much more than new carpets and a fresh coat of paint. “Our philosophy is to save anything that is good and take out anything that is bad,” he said. “What that means varies a great deal from apartment to apartment, but we are replacing all the air conditioning and the roofs. We are also filling in most of the swimming pools and converting them to flower beds.”

Rudy’s goal is to create a quiet atmosphere that will attract tenants between the ages of 25 and 45. “We’re not after what the media call the swinging singles clientele,” Rudy claimed. “We are not attempting to avoid young people, but we do want to get tenants who are settled and established. We want people who see this as a last move before a house or as a post-home move.”

Whatever Rudy’s tenants turn out to be like, they will have to have higher incomes than the occupants of the past. Rents in the area when Rudy purchased his units last year were about $125 to $300 per apartment. When the restoration is done, they will range from $220 to $450.

Rudy says that if St. Regis Place is successful, he will still continue to rework old houses in Montrose, but may also branch into commercial renovations in the downtown business district. “I’m still looking around,” he grinned. “All sorts of things are open.”

Luxury Road

If the Midlane apartments are the old Chevrolets of Swinglesville, the Oaks of Woodlake is the new Cadillac. Located a few blocks from the busy Southwest Houston intersection of Westheimer and Gessner, the complex is surrounded by thick stands of oak and pine. The architecture features brown or white stucco facades with plenty of wood trim. Levering and Reid, a Houston firm, began building the 952 units six years ago. They have since sold 556 of them to American Invesco of Chicago, which is now selling the apartments as condominiums priced from $30,000 to $70,000. The only section still renting as apartments is the 396-unit Oaks of Woodlake Phase III, which was built two and a half years ago.

Amenities abound. Among them is the Woodlake Community Center, which features five tennis courts, two air-conditioned handball courts, and conference and party rooms. Phase III also has its own separate clubhouse with fully equipped exercise rooms and saunas, party rooms, redwood decks, and barbecue pits. In order to insure a properly civilized atmosphere, there are only two swimming pools, no family sections, and no disco club.

“Most of our tenants are highly professional people,” explains leasing manager Sher Johnson. “The average age is in the thirty to thirty-five range. They don’t like to have noisy clubs on the complex grounds.”

The one-bedroom apartments at the Oaks of Woodlake Phase III are available in five different floor plans: Red Oak, White Oak, Water Oak, Pin Oak, and Post Oak. They range in size from 639 to 973 square feet and rent for $289 to $419. The two-bedroom apartments, called Chestnut Oak, are 1250 square feet, about the size of a small two-bedroom house, and rent for $474 to $514. All the units have brick fireplaces that actually work and nine-foot ceilings in every room. The apartments on the third level of each section also have cathedral ceilings in the living rooms. The carpeting is not the nylon shag found in most apartments but, as the brochure accurately describes, “a fine grade of beautiful carpet in a neutral champagne color.” The drapes are “custom-made raw linen.”

Many tenants consider two of the greatest attractions to be the design and landscaping. Instead of the monotonous, perfectly square layout common to many of the big complexes, the streets and driveways at the Oaks of Woodlake are winding and decorated by islands of ligustrum and neat flower beds. They are also immaculately clean.

“The maintenance men literally vacuum the streets every morning,” Johnson said. “They actually come along with little machines that suck up all the dirt and leaves. It’s really amazing.”

The apartment sections are also arranged in curvilinear patterns. But this, alas, doesn’t entirely satisfy the conscious effort to be unique. The separate sections at the Oaks of Woodlake look just as much alike as the separate sections at Napoleon Square. And with all the nifty curves and angles, individual apartments are even harder for a visitor to find.

“You just have to provide your friends with lots of maps,” Johnson offered cheerily.

Perhaps the best summary image of the place is the sight of a trim young woman in purple shorts, a dashiki, and a white sun visor jogging down the grassy esplanade on Gessner with her blonde ponytail flopping in the breeze.

H.H.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston