This night life ain’t no good life, But it’s my life.” *

Willie Nelson wrote “Night Life” more than fifteen years ago—before he’d even moved to Nashville let alone returned—and sold it for $150. Of all the songs he’s written—literally hundreds, including some great ones—it’s probably been recorded by the most performers, more than seventy at last count, ranging from B. B. King to Rusty Draper to Frank Sinatra. A classic barroom lament, the sadly proud confession of a loner’s desperation, it touches everyone who’s ever clung to night in despair of the day.

Aretha Franklin’s version, Willie’s personal favorite, has a desolate uptown sound, bluesy yet brave, an affirmation reeking of pain and expensive gin. You can almost see her, all satin and ice, standing haughtily in the middle of Lenox Avenue and praying to the streetlights. Willie sings it from the roadhouse parking lot, empty gravel by the highway’s edge, wailing back at the neon challenge. He’s more defiant but less confident, his voice raw and a little dangerous, too many straight shots of bad liquor. In their different ways, you can tell, both performers have been there.

Willie, in fact, had been there all his life. Born a mere gospel shout south of Waco in 1933, raised by grandparents and assorted aunts, he played his first dance hall at the age of ten in a band with his sister Bobbie on piano and the local football coach on trumpet. It’s been night life ever since. He peddled Bibles and vacuum cleaners door-to-door, pumped gas, joined the Air Force, scrubbed floors, disc-jockeyed, and dishwashed: the days, then, the days were barren and demeaning, forgettable failures one after another, a life to be denied. It wasn’t till the sun flared out and the neon flickered up, with Bob Wills calling everyone to “Dance all night, dance a little longer,” that life truly began.

By the mid-fifties Willie was living in Fort Worth and playing for beer or occasional whiskey in Jacksboro Highway honky-tonks. A regular Sunset Boulevard for rednecks, the Jacksboro strip is a single frenzied, five-mile-long barfight behind a facade of honky-tonks. Located just outside the city limits, far afield of law and property, it was a place where, in the years Willie Nelson was around, the management put chicken-wire fences in front of the stage so performers wouldn’t get hit by flying beer bottles. This was night life with a vengeance.

As the man said, though, it was his life—and he reveled in it. Aside from minimal aerial security he wanted his audiences as raucous and alive as he was, maybe even a shade reckless, as he also was. Willie Nelson was pure, unrefined redneck, and the honky-tonk is the vital focus of redneck culture—what the saloon was to an earlier Texas—the center of energy because of the very tensions it excites. If the honky-tonk world seems darkly colored with loneliness and loss—if it oftentimes ain’t no good life—then it’s only the moonlit image of the larger culture. And if anyone wanted to dance all night, then Willie was ready.

He started to write in the early Sixties, sold his first song, “Family Bible,” for $50, and saw Patsy Cline make it a huge success. He quickly followed with “Night Life,” a hit for Ray Price, then it was off to Nashville in a battered old ’41 Buick. In the next ten years Willie Nelson wrote some of the finest music in the country repertoire—“Hello Walls,” “Crazy,” “Yesterday’s Wine”—and commanded yearly royalties in six figures and a niche in the Nashville Songwriters’ Hall of Fame.

His songs for the most part were typical country numbers on typical country themes, plaintive evocations of daily sorrows and sorry days, as simple and disquieting as classical tragedy. But subtleties emerge: there was never any pity in a Willie Nelson song, none of the banal hand-wringing so common to Nashville music; there might be anger, grief, confusion, even defeat, but never the surrender that pity implies. Nor is there any blame, another cheap refuge for small minds and bad art; Willie Nelson was, is, forever will be a rank male chauvinist, yet even his most painful divorce songs refuse to throw stones. He is a songwriter of grace, sensitivity, and compassion, qualities as rare in that profession as in any other.

He is not what you’d call sophisticated, either in his lyrics, his melodies, or his ideas, but sophistication has never been a hallmark of the country tradition—or, for that matter, of American art in general. On the surface Willie’s styling is relentlessly ordinary and everyday like a Japanese haiku, but the real measure of his songs is the truth of perception and the depth of our recognition. Any metaphor, however commonplace, that can vault cultures with a single insight, that can intersect Lenox Avenue with the Jacksboro Highway, is nothing less than powerful art.

It was Willie’s flawless misfortune, though, to arrive in Nashville just when the Snopeses took over and the grits turned to mush. Hankering after the torpid but lucrative pop market, country music abandoned honky-tonks for Harrah’s in Tahoe: it became “easy listening music,” shallow vocals floated in vanilla arrangements, all strings and no sting.

Willie’s songs made the transition of course. They seemed to work everywhere—not even Andy Williams could ruin a song like “Funny How Time Slips Away”—but Willie himself never made it. He was just too rowdy and real to ever make a credible nightclub act. Over a dozen Willie Nelson albums were released during his Nashville years, usually showcases for new songs, and they all disappeared as soon as a few “stars” had covered the tunes. He’d had a modest hit when he first got to town, his own “The Party’s Over,” but that was the only one. And it was a dozen years before he’d have another.

And all the while it was on the road, restlessly migrating to the next inevitable honky-tonk in a long stoned blur of neon BEER signs, freeze-frames in the night life. There were bad debts, deals, dreams, failed promises and marriages, and lots of folks who wanted to dance all night.

It’s been rough and rocky traveling

But I’m finally standing upright on the ground,

After taking several readings

I’m surprised to find my mind’s still fairly sound,

I guess Nashville was the roughest

But I know I’ve said the same about them all.

We received our education

In the cities of the nation,

Me and Paul **

I met Willie Nelson on a Saturday afternoon in March 1970 when I wandered into Roy Evans’ living room in Austin and found this quiet little man perched on the back of an armchair, his feet on the cushion, strumming an apparently prehistoric guitar. He was wearing gabardine slacks, a tacky yellow Robert Hall’s shirt, and seemed terribly shy. I’d been told he was a “famous country songwriter,” which didn’t impress me—I was a graduate student then, very young and superior—but I liked him from the moment we shook hands and he smiled at me: it’s what everybody first responds to in Willie, that tremendously embracing smile. His hair was still pretty short in those days, no beard yet either, and his face was plain bad luck and lumps. He looked to be the quintessential cedar-chopper except, I noticed, for the tiny gold ring piercing his left ear.

His home in Nashville had burned down a few months earlier, the only things rescued with a mad dash into the flames being his guitar and his dope stash. Willie was passing the winter on a deserted Bandera dude ranch with his family and The Family, his odd coalition of flunkies and friends. He did a lot of writing that winter, some of the best he’d ever done, including the sharply introspective roadsong “Me and Paul,” about himself and his twenty-year sidekick, soulmate, and drummer, Paul English. Drawn irresistibly and practically nightly to Hill Country dance halls and honky-tonks, he was slowly rediscovering Texas, taking some readings, finding himself.

He found himself in Roy Evans’ living room because Evans, then the state AFL-CIO president, had recruited his old buddy Willie to play a benefit concert for Ralph Yarborough, the labor-backed U.S. senator who was campaigning for reelection. And I was there to help promote the benefit. I’d never heard of Willie Nelson, but Evans assured me his fans were legion within the ranks of organized labor.

This was a somewhat exaggerated claim, I suspected, but it proved sufficiently accurate to surprise me. George Meany couldn’t have attracted a better crowd. None of the union members had to pay, however, and since not much of anyone else came, the benefit was sort of a loser. There definitely weren’t any “hippies” in attendance, not with all those hard hats around. The hottest single on the country charts that winter was “Okie from Muskogee,” Merle Haggard’s cheap broadside against dope-taking, free-loving, flag-burning hippies. Virtually a redneck anthem, the song was everything a Willie Nelson song was not: petty, self-righteous, strident, the musical version of a Spiro Agnew speech. Though in certain respects a more talented musician than Willie, Haggard lacked all those personal graces that make the difference between talent and art. Without the sensitivity to achieve insight he relied instead on posturing and pretense, his song such a parody of itself that barely six years later it’s already become a nostalgia item, and probably an embarrassment. Willie’s songs, by contrast, invariably carry the same power of perception as they did when they were written.

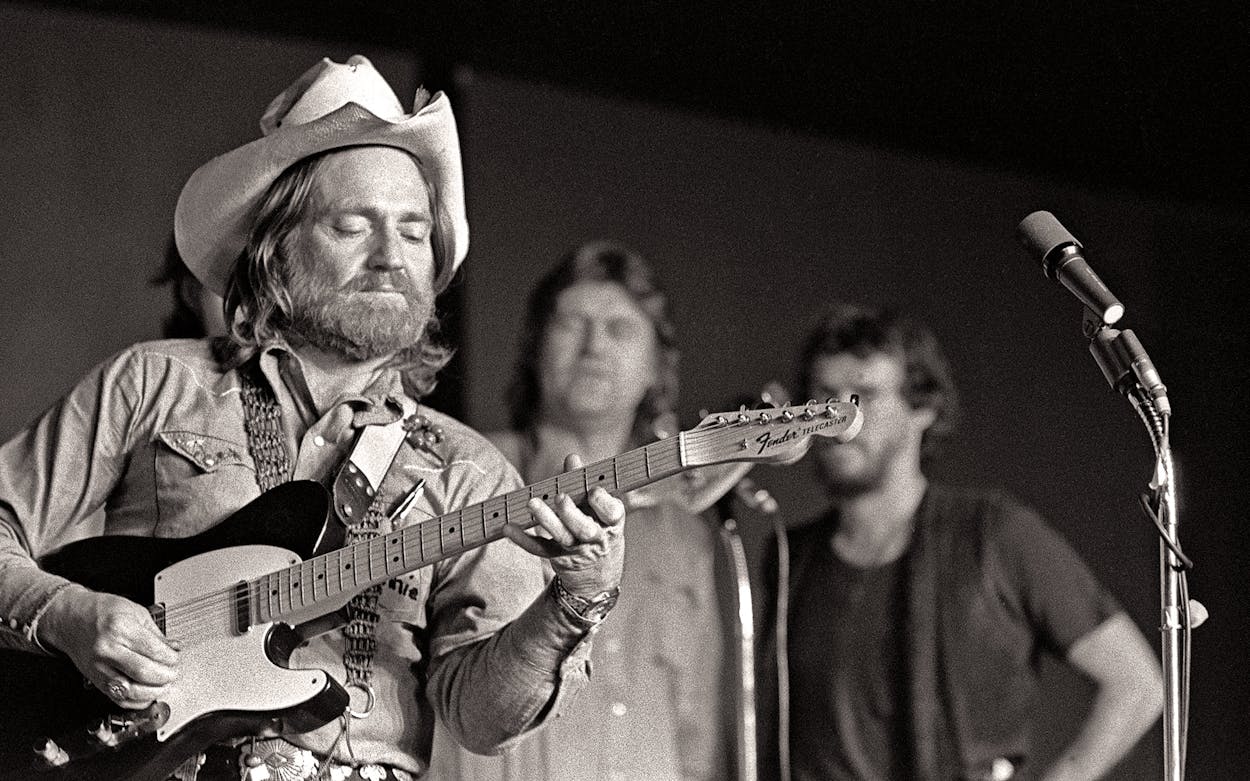

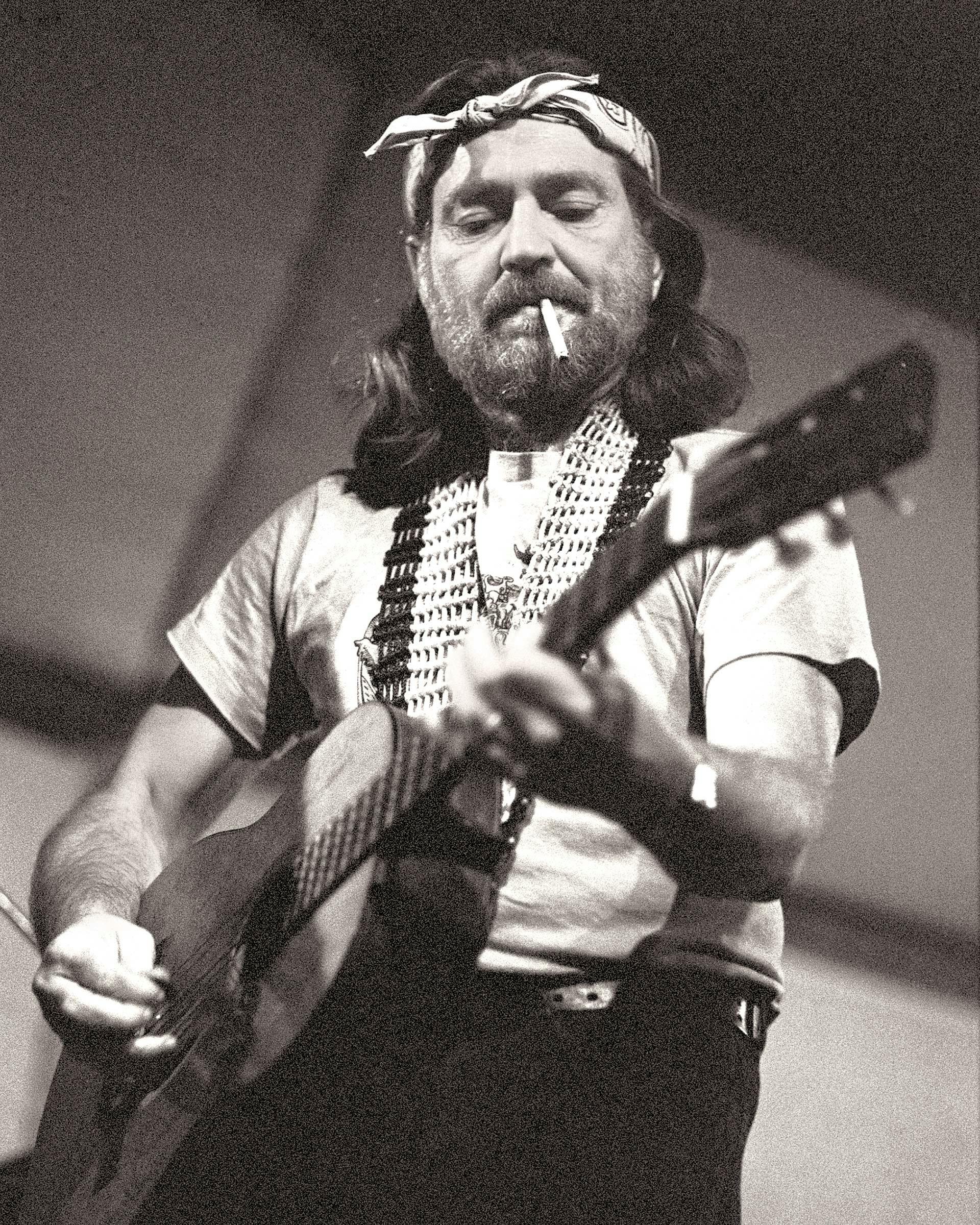

But what really struck me about Willie Nelson, that first time I heard him, was that he’s one helluva guitar-picker. Not a virtuoso in the manner of Chet Atkins, say, or numerous other Nashville technicians, he’s rather a stylist possessing an original, identifiable signature. Closer to blues than standard country, more fluid and less rhythmic, it’s a richly intoned sound with a faint upbeat embellishment, almost a flamenco trill, a hint of anomalous whimsy like the ring in his ear. Willie was still pretty much of a honky-tonker back then, but his concert generated all the energy and intensity of the best rock ’n’ roll with generally greater spontaneity, and it trashed all my smug illusions about country music.

They were obsolete illusions in any case. The official Nashville brand of country music was quickly fading into pale, languid stupor, suitable for funerals or the Johnny Carson show. When Willie went back that summer he attempted to stir up some excitement, or at least some trouble, but Nashville keeps its stars on short leashes and his kept getting jerked. Johnny Carson just wasn’t Willie’s idea of night life, so after a fruitless, frustrating year he decided to quit Nashville entirely—about the most radical decision you can make in the country music business—and moved to Austin where his sister Bobbie lived.

Playing around Texas he began to notice occasional, presumably audacious longhairs infiltrating his familiar honky-tonk crowds and became intrigued. He looked around some more, played for and with some of them, and sent word back to his fellow Nashville troublemakers that these kids might have the makings of a fair country audience. An unlikely alliance was about to be joined.

The basic cultural distinction between rednecks and hippies, Willie once observed, is that “whiskey makes you feel like fightin’, and marijuana makes you feel like listenin’ to music.” And so long as that’s all there was to it, Willie figured he could handle things: he was a recognized authority, after all, on the whiskey-and-fightin’ scene, and he’d been fairly well acquainted with the marijuana scene ever since helping his folks plant it in the cornfields south of Waco. It was merely one more approach to all-night dancing, and that was OK by Willie. He even started letting his hair grow.

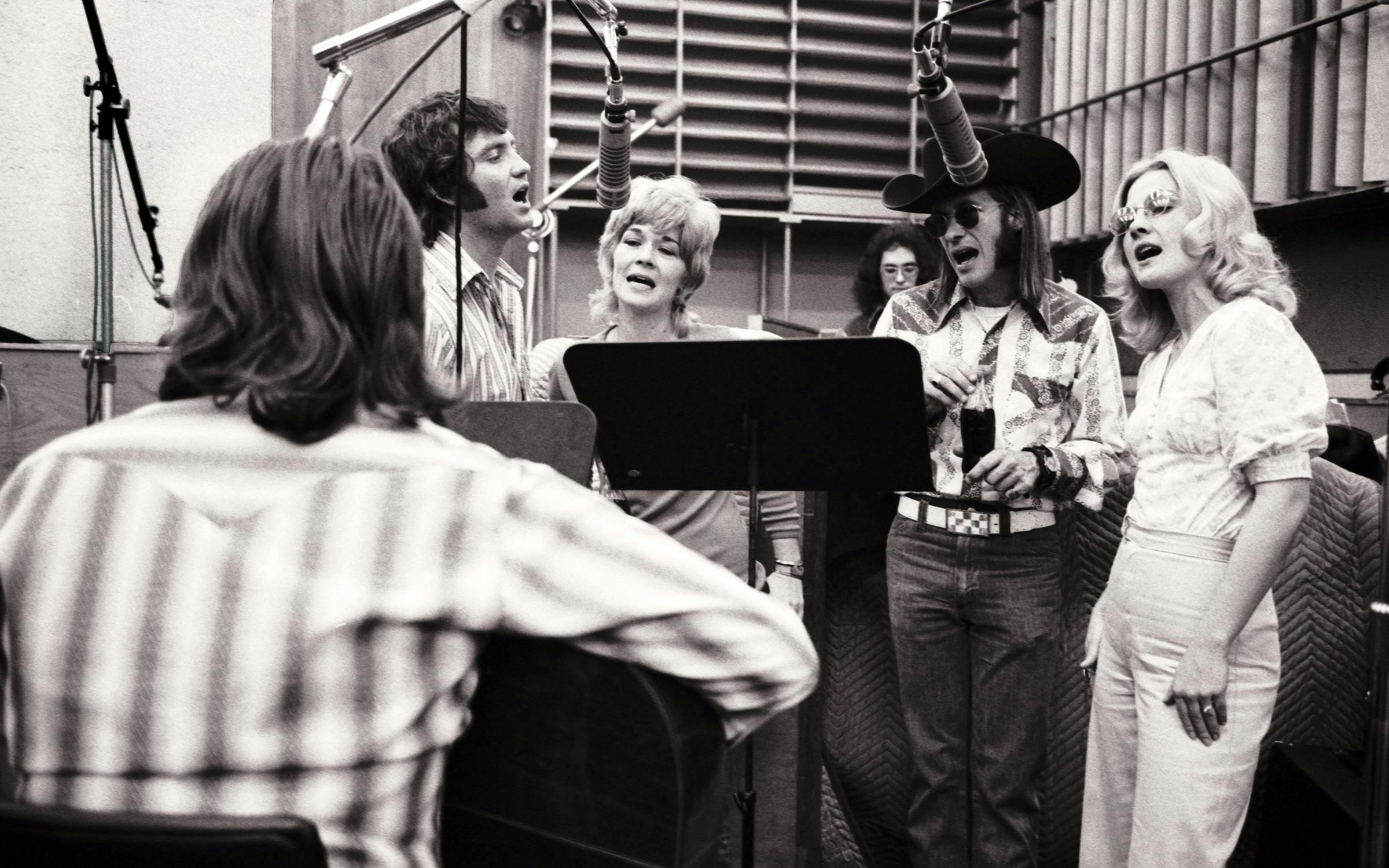

And when he showed up in New York to record an album for his new label, he brought his road band along with him. It was the customary practice for a rock ’n’ roll band but a brash departure for a country singer, whose backup support virtually always is provided by studio musicians. It was the first album Willie ever enjoyed any degree of personal control over, and it came out sounding more raucous and rowdy, more like his live performance than any recording he’d done before. The album was Shotgun Willie and it was a runaway hit.

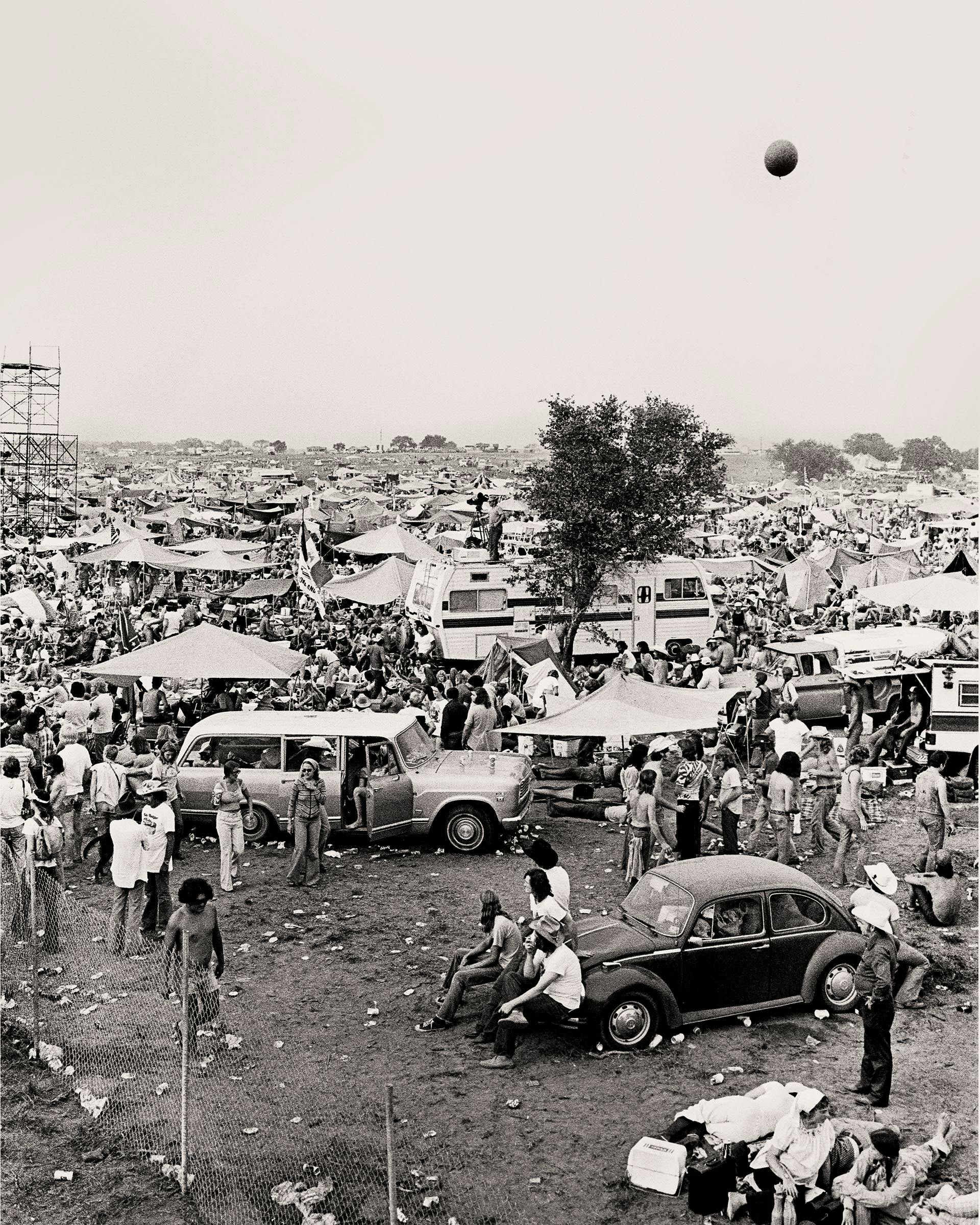

He celebrated the album’s release, and also his fortieth birthday, with a full-dress performance at Armadillo World Headquarters, Austin’s answer to Caesar’s Palace, in April 1973. Three months later came Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic, and within the year there were landmark albums from Jerry Jeff Walker, Waylon Jennings, Michael Murphey, Doug Sahm, Kinky Friedman, and a veritable studio-full of Austin sidemen. It was the beginning of something.

“Well I’m wild and I’m mean,

I’m creatin’ a scene, I’m going crazy.

Well I’m good and I’m bad,

And I’m happy and I’m sad,

And I’m lazy.

I’m quiet and I’m loud

And I’m gatherin’ a crowd . . . ” ***

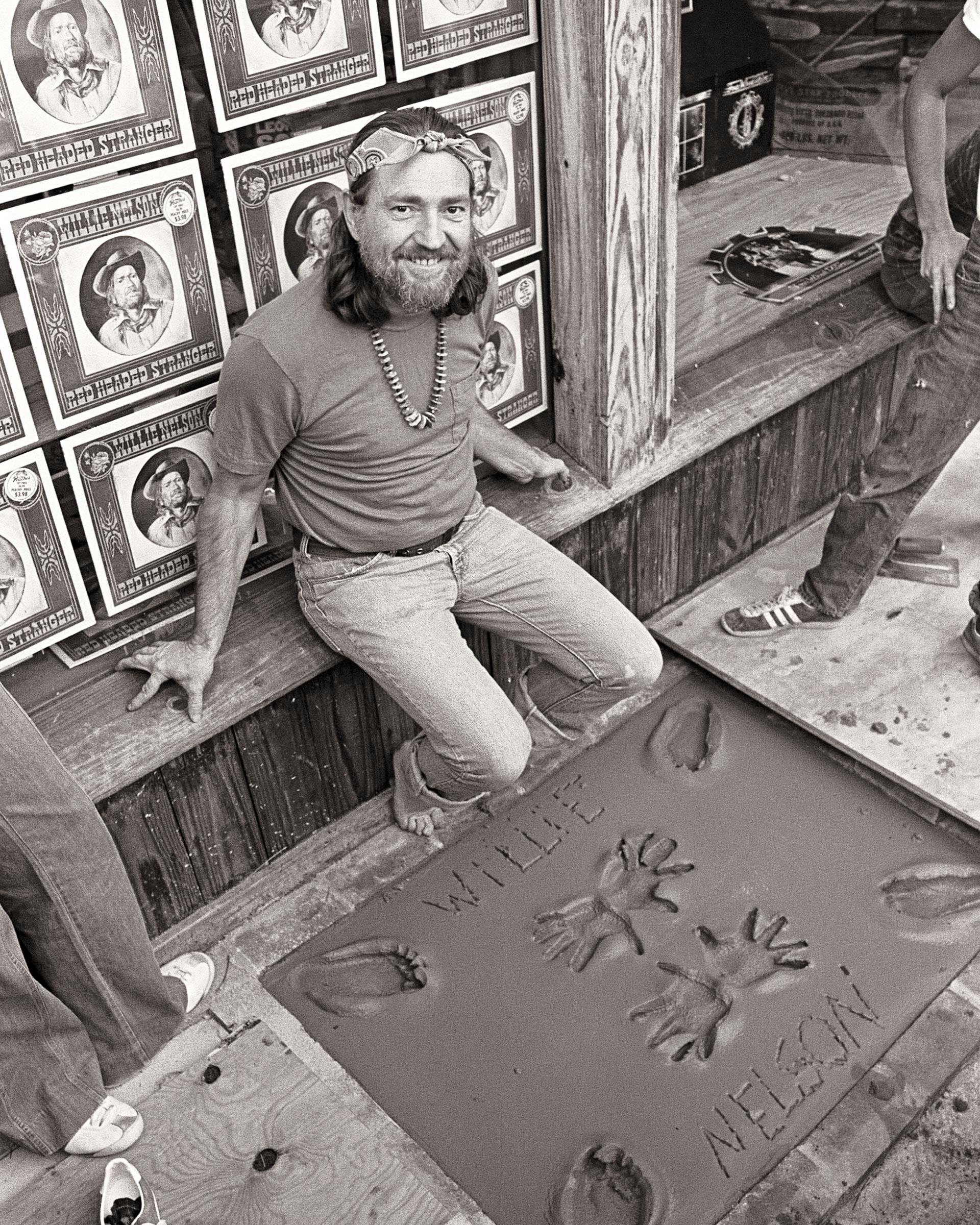

It’s all happened so quickly: “redneck rock,” “progressive country,” “Austin music,” “Texas music”; whatever it is, it sure got here in a hurry. Austin hasn’t had a unifying obsession like this since 1969, when the Longhorns were national champs. Of course there’s a lot of posturing and pretense involved, silly mooning over Outlaws and such, the embarrassments of parody. But there’s also a lot of vitality in Austin right now, and vitality is the essential ingredient for producing new art. And Willie’s in the forefront, the vanguard. His latest single, “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” a 1945 tune reworked from his boyhood band days, recently became the biggest crossover country hit since Charlie Rich’s “Behind Closed Doors.” And The Red-Headed Stranger, the album it came from, won a Grammy for best country album in 1975. The Fourth of July Picnics are front-page news, and the national journals, musical and political, have tried to figure out who Willie is and what his music means. Texas has always provided the cutting edge of country music, nothing new about that, but it took Willie to transcend Nashville and bring it back where he started.

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson

- Austin