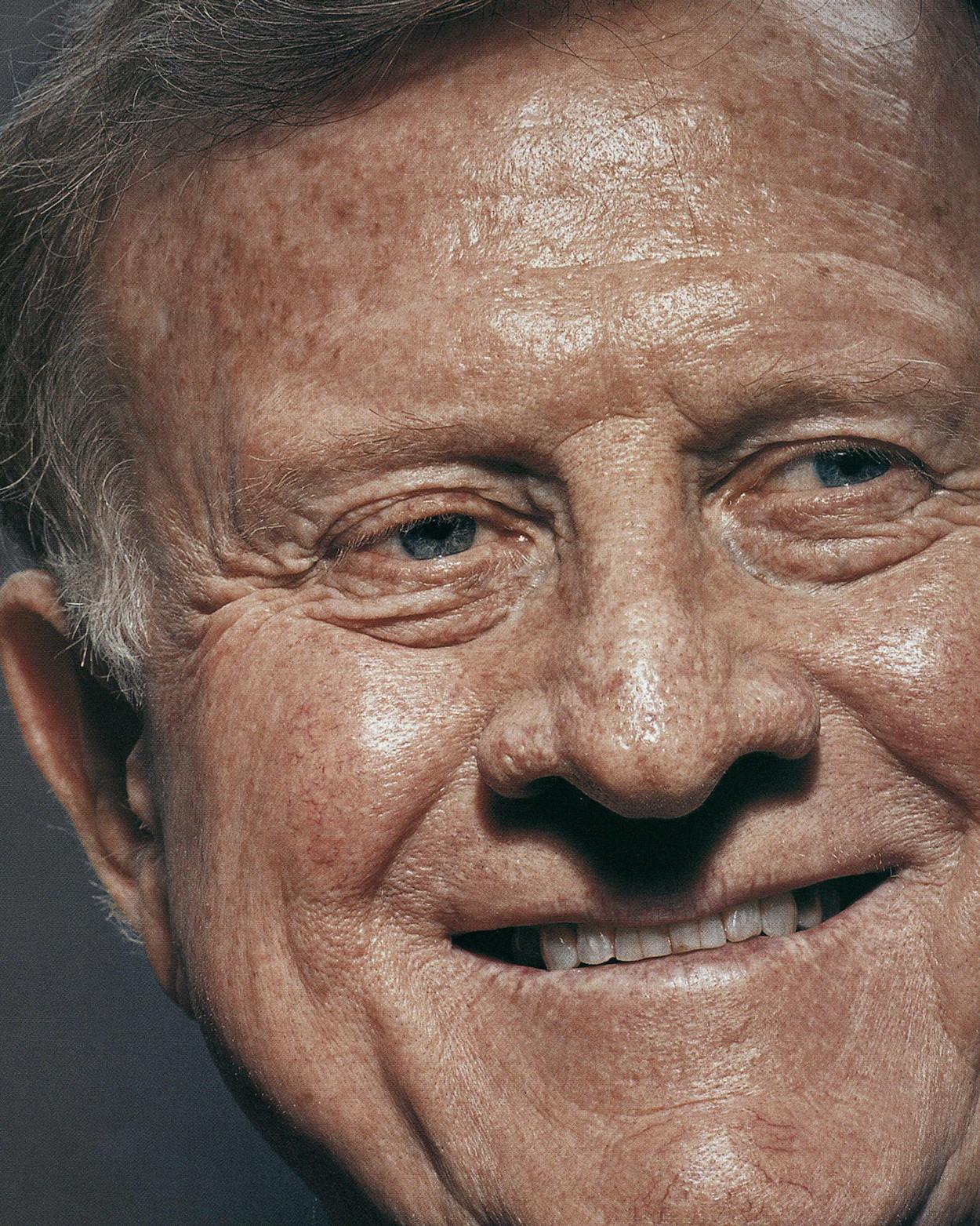

On a Saturday morning in May, B. J. “Red” McCombs, San Antonio’s billionaire car dealer, oilman, rancher, broadcaster, real estate magnate, and all-around sports addict, found himself pacing up and down the sidelines, as is his habit. “Take no prisoners!” screamed the exuberant 71-year-old, who stands six foot three and has large red-tufted hands and a face full of freckles. “Come on, Joseph! Hit that ball!”

The ball was a baseball, as in machine-pitch baseball—as slow and awkward as any game—and the Joseph in question was McCombs’ ten-year-old grandson. The shy, sweet boy glanced nervously at his grandfather, whom he calls Pop-Pop, before facing the creaky windup of the contraption on the mound. After missing the first two pitches, he smacked the third, and it sailed long and low over second base. Joseph was so relieved as he ran to first base that he practically floated along the base path. “What a hit!” yelled McCombs, turning a finer and more precise shade of—what else?—red.

The last time McCombs was that animated was a few months before, on January 17, when his newly acquired professional football team, the Minnesota Vikings, came within a single game of making it to the Super Bowl. After the Vikings lost to the Atlanta Falcons in overtime, 30—27, he lingered on the sidelines of the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome and groaned, “I never thought we weren’t going to win the Super Bowl. I just can’t grasp it.” That kind of sentiment might sound corny or contrived coming from some people, but not from McCombs, whose can-do approach to every business he’s in, sports included, is a throwback to an earlier era. He really thinks he can will himself to succeed, and maybe he’s right. When he outbid best-selling author Tom Clancy and other high rollers and paid $250 million for the mediocre Vikings, he seemed to be in need of psychological help. But after their best season ever—they went an amazing 16—2—it was the rest of us who had to have our heads examined. We never should have doubted him. You never underestimate Red McCombs.

When he’s in San Antonio, McCombs heads to his office bright and early to attend daily seven-thirty meetings. He owns half a dozen skyscrapers and could have his pick of the swankiest suites in town, but instead he works out of a small space above one of his busy Ford dealerships off Interstate 10, where he can mingle with his salesmen as they chat up customers. “I like the action,” he says. “I like seeing the public.”

Most days he wears khakis, an open-collar shirt, and boots—“I’m a red-necked, tobacco-chewing Bubba,” he brags—and carries a cowhide briefcase with a bumper sticker affixed to it that reads “God Bless Texas.” Along with his private jet and his fleet of automobiles, which includes a custom-made silver Rolls-Royce, he owns a herd of Longhorns, several ranches, a collection of Western art and artillery, and four heavy silver saddles made by Edward H. Bohlin, Hollywood’s saddlemaker to the stars. “All I wanted out of life was to be the go-to guy, the guy who was in a position of power to make the decisions that really matter,” he says. “I used to think of myself as the little dog that kept chasing the big shiny red fire truck. I finally caught up with the truck, and I know what to do with it: I want to ride.”

Billy Joe McCombs was born on October 19, 1927, in Spur, a town of fewer than two thousand about seventy miles from Lubbock, into a family in which the ability to make cars go and trucks shine was taken seriously. His father, Willie, was a mechanic who worked for the town’s only Ford dealer. Willie had a third-grade education, but Red says he could “instantly diagnose a mechanical problem and see the solution.” One of Red’s strongest memories of his father is of watching him look through mountains of scrap metal in junkyards on the weekends, searching for just the right parts.

Spur wasn’t just Red’s home; it was his first market. At age nine, he sold peanuts to itinerant Mexican farmworkers—and figured out that he could improve his margins by putting fewer peanuts in each bag. At age eleven, he washed dishes after school in a cafe in downtown Spur, then got up at five in the morning and delivered newspapers. No one, least of all Red, knew exactly where he got his drive. Perhaps it had something to do with his father’s unrealized ambition, but at any rate it was ferocious. “Nobody knew what an entrepreneur was in the 1930’s and 1940’s, but I was one,” he recalls. “All I knew is that I wanted to have enough money to buy Arrow shirts.”

One day in June 1943—a day that McCombs says he’ll never forget—Willie moved the family to Corpus Christi, where he went to work at the naval air station. Red realized that both his father and his hometown had lost their place in the world because, as he puts it, “they didn’t have a hook—they had nothing to sell.” Spur was not a county seat and had no college or large employer; it couldn’t compete with larger cities for the manufacturing plants that were being built to supply the troops during World War II. The lesson seemed clear to him: Always have a hook.

Though his father eventually made more money at the naval air station, McCombs was so unhappy about the move that at first he would not leave Spur. He stayed there alone that first summer and worked full-time at the local drugstore. “My scope was never that big,” he says. “I would have been perfectly happy living in Spur forever. The way of life there was my identity, and I didn’t want to leave it.” In August, however, his mother, Gladys, a strong-willed Baptist who was the dominant force in the household, became worried about her son getting into trouble. She drove back to Spur and insisted that Red rejoin his family (which included a younger brother, Gene, and two younger sisters, Mildred and LaWanda). When he refused, Gladys did not hesitate: She picked up a tennis racket, swung at him, and knocked him down. “Billy,” she told him. “I don’t want to hit you again. Go get in the car. We are leaving Spur.” He had no choice but to obey.

At first he was devastated, but within a few days of arriving in Corpus, he was playing football on North Beach, and he realized that he’d found a new hook. From then on, he ascribed to sports an almost limitless power. He began the long struggle to organize his life around what seemed for years like mutually exclusive goals: playing sports and making money. In high school he was good enough as a tackle and an end to enroll at Southwestern University in Georgetown in 1945 with a scholarship. Yet after his first season, he was scheduled to be drafted into the Army, so he enlisted.

Sixteen months later, in the summer of 1947, he was in line to register for classes at Corpus Christi Junior College (now Del Mar College) when he met Charline Hamblin, a longhaired brunette with green eyes. He immediately asked her for a date. “At first I wasn’t really too impressed with Red,” she says. “He was a jock and he had a big car—naturally it was a Ford—and he talked a lot. I hardly got a word in edgewise. But I liked him.” She learned early that football was not something he would outgrow. When it came time to set a date for their wedding, he asked if it could be a Thursday—November 9, 1950—so that he would be able to watch Texas Christian University play on Friday night and Southern Methodist University play on Saturday.

Not long after they got married, McCombs—who never graduated from college—dropped out of his second year at the University of Texas Law School. He decided that the world he’d grown up in, in which lawyers, bankers, and doctors held most of the wealth, had changed. “I found out what friends of mine who were beginning lawyers were making, and it didn’t seem like enough, so I left school,” McCombs recalls.

A friend in Corpus offered him a job selling Fords, and he took it because the friend explained that he could shoot pool in the afternoon and promised to give him a new car to drive. Still, McCombs told himself that he would sell cars for a maximum of six weeks. “I set a short-term goal for myself to sell one car every single day,” he says. “I just didn’t leave work until I sold a car.” Six weeks later, McCombs was the top car salesman in the city. He’d found his niche and, more important, his three foundations of business success: writing down day-to-day goals, getting personally involved in the business, and paying attention to details.

In 1953 he opened his own used-car business in Corpus and picked up extra money by selling auto insurance to customers. Soon Edsel awarded him his first new-car dealership. He was such a good salesman that he could even sell the industry’s most notorious flop: His franchise was one of the few in the nation to turn a profit. The next year, McCombs was feeling a little flush, so he spent $10,000 to buy his first sports team: the Corpus Christi Clippers of baseball’s Big State League. “When I bought the Vikings, I was asked how it felt to pay that much money for a team,” McCombs says today. “All I could think of was that it was no big deal compared to the risk I took with the Clippers.” The reason: $10,000 in 1954 was a much greater percentage of his total assets than $250 million was in July 1998.

Four years later, in January 1958, McCombs moved to San Antonio and went into partnership with Austin Hemphill, who owned a Ford dealership. During the next two decades, McCombs bought out Hemphill and started more than 25 new dealerships in the Southwest. He began branching out in almost every conceivable direction. A large investment in one bank, South Main in Houston, led to other investments in other banks. The purchase (with partner Lowry Mays) of San Antonio’s largest radio station, WOAI, led to the founding of Clear Channel Communications, which now owns or operates more than seven hundred stations around the world. Investments in hotels led to investments in restaurants (he is a part owner of the Old San Francisco Steak House chain), which led to underwriting movies, including The Verdict and Romancing the Stone. “My unbreakable rule is that I don’t buy into things I don’t feel a personal passion about,” says McCombs. “The trouble is I feel passionate about a great many things. I hurt when things go wrong, and I feel a great high—positive elation—when things go well.”

One thing McCombs has definitely felt passionate about is San Antonio itself. After HemisFair in 1968, he turned his attention to helping the city solidify its identity. Five years later, he and a business partner, Angelo Drossos, leased and later bought the Dallas Chaparrals of the old American Basketball Association and moved them to San Antonio, where they were rechristened the Spurs after the local newspapers held a name-the-team contest. Even today McCombs has strong ties to the Spurs, which he has owned twice (he sold his interest in 1982, bought the team again in 1988, and sold it again in 1993). From his front-row seat, he cheered wildly for the Spurs over the Minnesota Timberwolves in the first round of the 1999 NBA playoffs, even though he now has an allegiance to Minnesota.

The seventies were an important period in McCombs’ life for another reason: That was when he realized he had a problem with alcohol. He was never a falling-down drunk—he never even appeared to be tipsy. To this day, Charline does not believe that he is an alcoholic. “That’s how insidious this disease is,” McCombs says in response to his wife’s disbelief. He knew that he was an alcoholic because, he found, he couldn’t live without booze: At first he drank mainly beer, then mixed drinks, and finally graduated to vodka because it’s clear and odorless. At two in the morning on November 12, 1977, almost one month after he turned fifty, he awoke at his home and went into convulsions. He was taken by ambulance to a hospital and later transferred to a hospital in Houston. “My liver and kidneys just quit working,” recalls McCombs. On the sixth day he was conscious enough to start praying. “I had only one prayer: ‘Please, God, get this monkey off my back,’” he recalls. At some point the urge to drink left him; his will to live was stronger than his desire for alcohol. “God gave me a second life. I don’t know why, but I’m very sure of it,” says McCombs. “People ask me all the time if I’ll ever retire. Naturally, the answer is no. You don’t retire from a second chance.”

Soon after, McCombs found new, more profitable ways to channel what he describes as “my addictive personality.” During his recuperation, Charline took him on long drives through the Hill Country and urged him to “buy a little ranch so that we can relax.” They bought a five-thousand-acre spread about a mile north of the Pedernales River near Johnson City, and McCombs decided he would try to buy a small herd of cattle. He discovered that breeders did not sell their best Longhorns, which kept the price low—in 1978, about $700 a head. Once again McCombs saw a hook. He resolved to find a way to offer top-of-the-herd Longhorns to the general public.

That summer, he and Charline toured the South and Southwest in his airplanes, paying three times the going rate for the best cattle he could find. One of his stops was the King Ranch, which had never sold its Longhorns. He called Tio Kleberg, who ran the King Ranch’s cattle operations in Texas, and asked to buy from his herd. At first, Kleberg refused—traditionally, the ranch hasn’t sold its Longhorns—but eventually he relented, and McCombs picked out 26. When he inquired about the price, Kleberg told him, “Pay me what you think they’re worth.” McCombs took the top ten percent of the previous year’s sales of Longhorns, averaged them out, and came up with a figure. In 1980 the King Ranch’s Longhorns were part of the herd that McCombs sold for record prices at glitzy public auctions in the lobbies of the largest hotels in San Antonio and Houston: Breeding stock that once sold for $700 now sold for $3,000 and higher. In 1983 one of McCombs’ bulls, Redmac Beau Butler, sold at auction in Johnson City for $1 million. By the late eighties, the high-end market that McCombs helped create had run its course; today, Longhorn prices are half what they were at their peak.

In the years since, much of McCombs’ time and money has been expended on public causes. In 1989, for instance, he helped then-mayor Henry Cisneros sell San Antonio voters on building the Alamodome with a half-cent sales tax. But his greatest contribution has been his philanthropy. The foundation that he and Charline established in 1981 donates as much as $8 million a year to charities. In April 1997 they gave $6 million to Southwestern for the construction of a student center. The following month, after Jody Conradt, the director of women’s athletics at UT-Austin, told McCombs that women’s sports had no large benefactors, he wrote a check for $3 million. “I really felt bad that I hadn’t given money to women’s sports before,” he says. “I’m a guy, you know, and I gotta tell you: I’d never thought of it.” In 1997 he and Charline donated $1 million to complete the much-delayed renovation of the Empire Theatre, an architectural landmark in downtown San Antonio.

By that time, McCombs had restructured his business interests. In 1997 to focus more on commercial real estate and his new energy company, he made the decision to sell off most of his automobile franchises across the country, leaving only twelve in nine locations in San Antonio. “I’m drilling thirty new oil wells this year,” he says. “That may sound crazy, but I see a hook.” More recently, he’s been buying huge tracts of land in Colorado; he plans to divide them into ranches of various sizes, which, of course, he’ll sell.

After Joseph’s baseball game, McCombs drove to one of his used-car lots to have lunch—a plate of barbecue—with Charles Hutchings, who had sold 22 used cars in a month’s time. A small crowd of salesmen, for whom football is a secular religion, greeted McCombs at the front door like a deity. He rewarded them with an anecdote about another godlike figure: Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura, the former pro wrestler. Like many people, McCombs was stunned by Ventura’s victory last November, and he was anxious to talk to him because the Vikings will soon be seeking taxpayer funds to build a new domed stadium.

The day after the election, McCombs recalled, he arranged to telephone Ventura during the latter’s popular radio talk show in Minneapolis. “How are the Vikings doing?” cooed Ventura, a loyal fan, when McCombs got on the line. He then teased McCombs about the fact that the 1999 season was such a sellout. “My family and I couldn’t even get nosebleed seats,” he said.

As he related the story, McCombs assumed the pose of a fisherman who was terrified the catch of his life might be slipping off his hook. “I told Jesse he would never again have to worry about getting tickets to a Vikings game,” McCombs told his sales crew. “The next Sunday, when the Vikings faced Green Bay, Jesse showed up with his two kids, and he took his seat right next to me on the fifty-yard line.” Inside the circle of salesmen, McCombs beamed, and you had the feeling that this easy camaraderie—being one with his team—was the big payoff.