It happens all the time.

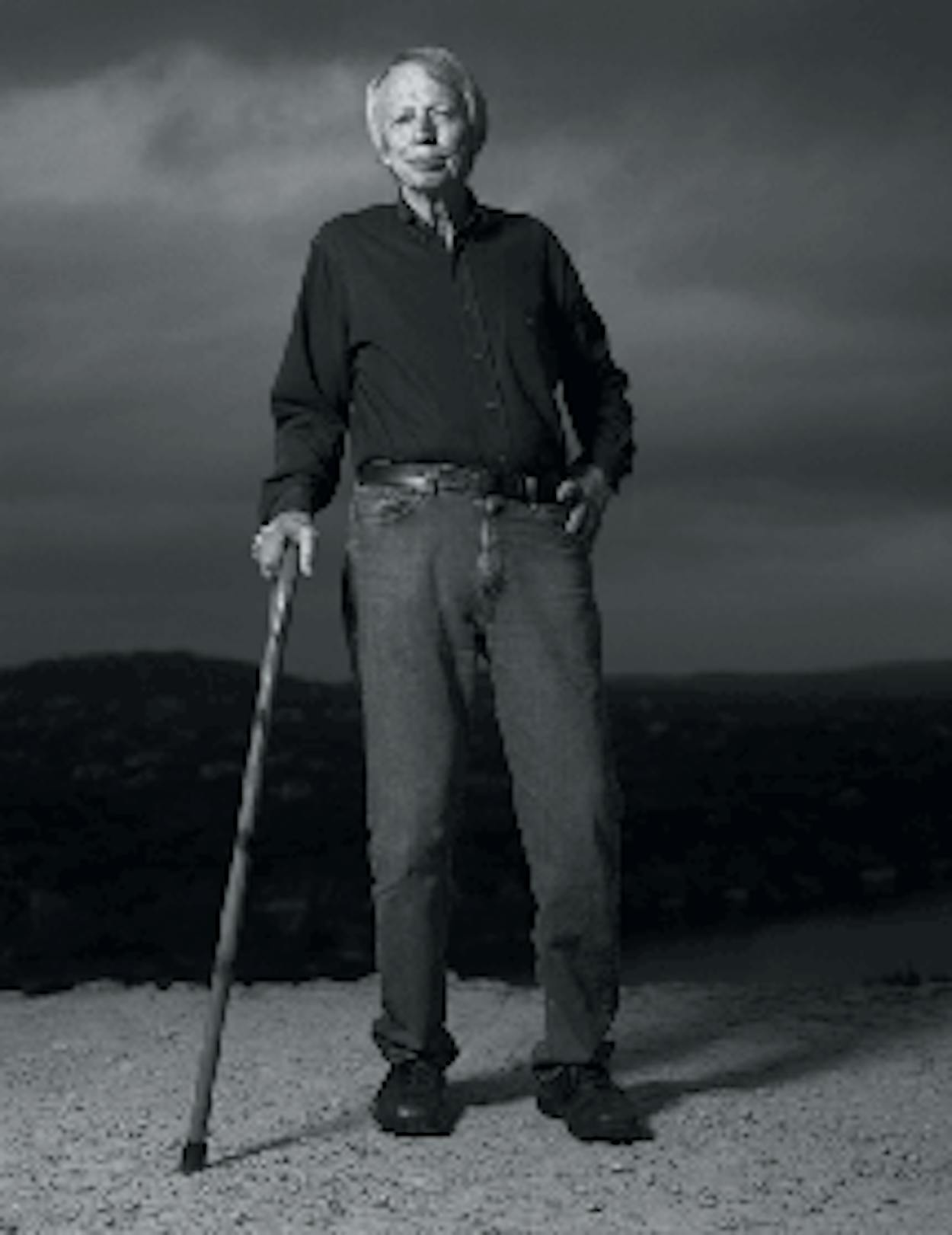

You’re driving along, mind on the political yammer of the day or what you forgot to get at the grocery store, when someone makes a mistake and eight thousand pounds of hurtling metal crash and come at last to a smoking, awful stop. Or you climb up on a roof where you know you really don’t belong, except those leaves collecting up there have begun to annoy you, and suddenly you’re airborne, heading for a landing that breaks your neck. Sometimes when people are kind or blunt enough to ask what happened to me—why I walk slowly with a cane—I reply, because I don’t want to tell the story again and have to see the shock on their faces, “Oh, I was in a car wreck.” Not that a car wreck is a trifle; those all-too-common crosses staked in bar ditches to honor a loved one are our most poignant art form. Sometimes I think of saying, to add some exotic spice to my story, “I got thrown by a mule.”

But the truth is, ten years ago this month, I was shot by a Mexico City thug at a distance of about fifteen feet. He looked me in the eye and meant to kill me, and he ran away assuming he had. Three friends—Mike, John, and Dave—crouched around me in panic and disbelief. We had gone off on a three-day lark. We would roam the streets of a vast and ancient city, act foolish, throw down shots of tequila, and lend some moral support to a boxer friend who had been deported (he has since resolved his difficulties with the immigration authorities, returned to Texas, and won two world titles). We were on our last taxi ride back to the borrowed apartment, our friend’s boxing match handily won and a fine trip behind us, when the cabbie jammed on the brakes, allowing his two gun-wielding chums to jump into the car.

In the blink of an eye, your life can change.

When the cabbie finally stopped on a street that looked like the urban end of all time and the thugs ordered us out, my survival instincts summoned me to try to fight, instead of making a run for it. To the extent that the Mexico City police expressed much interest in the matter, they maintained that the bullet, which went in just under my ribs, barely missed the aorta, ricocheted down several vertebrae, and was later plucked out by neurosurgeons, had been fired from a 9mm pistol. But 9mm’s are semiautomatics, and this was a revolver, an old scratched-up .38 caliber. I know what it was because the main thug had taken pleasure in hitting us over the head with this, and I’d gotten a pretty good look at it. A pistol fired at night ordinarily emits a trim, pointed blaze, like that of, say, a cutting torch. The thug’s .38 threw out a crackle of lightning that sparked crazily in front of his silhouette, from his head to the pavement. My point in going into such detail is to demonstrate the possibility that things could have easily gone the other way. That old gun could have blown up in his hand.

Time has a way of erasing terror and agony, or at least giving it a helpful blur. You don’t forget—the damage you carry around won’t let you—but you don’t dwell. I’ve never dreamed about that man and his gun. I wouldn’t know him if he walked up to me on the street. The way he spent his time, I have a hunch I’ve outlived him. When I tell people what happened, I always say, “I’m lucky to be walking at all.”

If I were religious, I’d use the word “blessed.”

The Mexico City doctors, nurses, and emergency technicians who came to my aid were as expert and dedicated as the police were indifferent and slipshod. They saved my life, and when my wife, Dorothy, and daughter, Lila, arrived, they gave them the care of compassion. Two Texas friends who came to the hospital knew that the one essential gift they could bring to our ordeal was their fluency in Spanish. Others caught flights just to be with us, to let us know we weren’t in this alone. The publisher of this magazine directed and facilitated the scramble to airlift me to Houston and get me started in physical therapy, once I astounded everyone in a postsurgical recovery room by moving my toes. The friends who were brutalized with me are all on the magazine’s staff. Dave had been celebrating his thirty-second birthday that night. Mike, John, Dave, and I have since observed and raised glasses of salute, wonder, and sharing to fortieth, fiftieth, and sixtieth birthdays. Mike and Dave have become fathers. We don’t talk much about the nature of our bond; we don’t have to. I’m the oldest, hobbling along at 63. I was the one, by virtue of my seniority, who was supposed to have had some sense.

Once upon a time, in that different life, I was an athlete. Never an exceptional one, but I was in terrific shape. On the downhill slope of life, I discovered that, of all things, I possessed some gift for boxing. I was just a gym rat, a banger of the bags. I could make them pop loudly enough that the genuine athletes, like my friend the future world champion, would turn to give the old guy a look. I sparred infrequently, in part because I never overcame the displeasure of being hit in the nose. I can’t remember what magic of stamina, combinations, and footwork I found in myself, but one hot spring afternoon the trainer who owned the Austin gym I worked out at commended me on a just-completed two-hour routine.

“Best workout ever,” I gasped. “On my forty-eighth birthday.”

He laughed and gave me a whomp on the shoulder. “You and George Foreman!”

Well, not quite. But those afternoons of escape and release were enormous fun. I’ve never beaten myself up over what happened in Mexico City, but I have to wonder what would have occurred if my instincts had compelled me to flee, not fight. A volatile mix of anger, fear, adrenaline, and—sure—testosterone spilled all over that scene. But I didn’t throw a punch at a man with a gun because, as a few women have inferred, I was crazy or because I’d toned up my muscles in a boxing gym. There was no time to think about my options, and I’m absolutely certain I was fighting for my life. A murderer, at least in the moral sense, shot me with what was probably a stolen gun. His bullet missed by centimeters what a Houston trauma surgeon told me was my “business district.” It wasn’t my time to go. But gone forever was any vestige of my youth.

A few days after I was discharged from a six-week stay in a small, justly renowned rehabilitation hospital in Houston, Dorothy and I went to see the spine specialist in Austin to whom I’d been referred. After our appointment, I was down a hall from the examining room when I heard him dictating his notes: “Patient is a pleasant and well-spoken man”—oh, thanks—“with incomplete paraplegia.” I really thought, “Who, me?” Then I had to laugh at myself. I was in a wheelchair! But it may have been the very next appointment when that doctor said, “I don’t blow smoke at my patients. I can tell from what I’m seeing here that you’re going to be out of that thing in six months.” Dorothy and I were stunned. We were in the elevator when I finally spoke: “Well, he sure told us what we wanted to hear.”

It ended up taking a year and a half of outpatient therapy to rid myself of wheelchair and crutches. I floundered and splashed in utter despair, trying to make my legs work in the shallows of the hospital swimming pool. Paralysis of any degree loads nuance and menace on the word “gravity.” One day I met an elderly former airline pilot who had survived cancer, but his bones had been turned almost to sponge by chemotherapy. Daily exercise in that pool had enabled him to stand erect and walk again. He adopted me, in a way. He pepped me up with locker-room talk of classic title fights and travel abroad, anything to keep me trying and smiling.

My physical therapist, an ever-cheerful young woman from Long Island in a line of work prone to burnout, also became my friend and godsend. I flopped around tumbling mats at her command as doggedly as I had once whacked the mitts of my boxing trainer, and I made progress in the pool, treading deep water at a sprint and beginning to walk on a submerged treadmill. With the help of the buoyancy, I felt my body remembering how to step and stride and roll my hips. Dorothy and I went to New York on a magazine assignment, and apart from bringing back a profile of a singer I admired, we measured up to the great beast Manhattan, with its blaring horns, thunderous racket of demolition, and buildings with restrooms that were built decades before there was any social, much less legal, obligation to help the physically impaired.

One day, back in Austin, in the home office where I now sit, I watched two young guys from the medical supplier roll the wheelchair out of our lives. After that I thumped along on a walker and in time graduated to two heavy steel crutches. In January, a friend splurged on a wedding in Venice. Dorothy and I accepted the invitation, then I told him I had to back out. I was terrified of the long flight and the lines for customs. But we never canceled our tickets, and then somehow we were in Venice, just nine months after I’d almost died. To my surprise, that first day there was the last that I used two crutches. I realized I could manage now with just one. Or believed I could. Late one night Dorothy and I and some other couples were in Piazza San Marco, marveling at the beauty and our good fortune. The weather was cold and clear, and mist rose from the canals. “Look!” someone said, pointing to the ground.

As we stared downward, the dark stone under our feet appeared to break up like fine crystal tapped with a hammer. At once I knew what it was. The temperature, somewhere in the twenties, had reached a certain flash-freezing point, and I was out in the middle of that large square surrounded by a thin glaze of ice. I inched my way out of it, with help. The evening of the wedding, at the end of the party, we came out into a thick fog and realized the lines of canal boats, the vaporetti, had closed for the night. I could make the hike back to the hotel, more than a mile, or curl up on a stoop. The wedding’s photographer walked out in front of us with a camera and tripod, and he managed to catch an image in the available light. With furry globes of streetlights reflecting across the paving stones, in the mist we looked like ghosts.

My daughter, Lila, was getting married that spring, and I told my therapist I wanted to be able to walk down the aisle with her using a cane, not a crutch. It became our mutual goal, and working hard three hours a week, we accomplished it. After the wedding, I danced with Lila, twirled her around laughing as I propelled my feet with shoves of the cane and we did the step my generation calls the push.

That first cane was the black metal variety with a thick rubber grip. I still have and use it as a backup, but it clanks with each step and makes an obnoxious noise if I drop it. And it looks as if it came from a hospital. Then Dave, who had endured our terrifying cab ride with a Panama hat on his head and a fat and sweaty robber in his lap, found a cane at a garage sale, painted burnt orange by a University of Texas fan. He had no way to know it was the perfect height for me; he just had an eye. He stripped the orange paint, stained the handsome wood, had my initials artfully engraved in the back of the handle, and adorned the front of the cane, just below the grip, with a milagro he’d picked up in a Mexican curio shop. Milagros are small, flat emblems often hand-tooled from soft metal and tacked onto personal possessions as a plea for good fortune (the word means “miracle” in English). They can be anything—a cross, a cactus, a sliver of moon. Dave chose as my milagro the form of a leg and a foot.

Now that I walked with a cane, people saw me coming in a store or restaurant, gave me a quick smile, and held the door open for me. I found I didn’t mind; if I got there first, I held it open for them. Navigating a crowded room, though, was trickier. People don’t look down, and they’ll accidentally kick the prop right out from under you. Because it was available, and one of my doctors wrote the request, I got a license tag for my car with a symbol of a wheelchair. Since my youth, I’ve been known and kidded for my pokey driving, but the tag itself seems to annoy some folks in traffic. I learned that in downtown Austin I don’t have to use up one of the oversized spaces for vans of the disabled. A traffic court judge told me that with those plates I could park at any meter and never have to put a nickel in it. Free parking—it’s my only perk.

Over the years, moving around the house or scuttling back and forth across the patio to my office, I would stick the cane in a wastepaper basket or hook it on a towel rack or bookcase and limp on at a fair clip, preoccupied by the day’s work. Camouflaged, brown on brown, the favorite cane would vanish. Like a set of car keys, I kept losing the thing and always when it was five minutes past time to go.

“What’s wrong?” Dorothy would ask.

“Help me find the stick!”

It was a virtual miracle that the .38-caliber bullet, after clipping off the end of a vertebra and making a downward turn of almost 45 degrees, plowed to a halt without severing my spinal cord, which would have paralyzed or killed me, period. But a spinal injury in that part of the column means that every bodily function below the waist is traumatized or weakened. Walking is just one of the extremely important things you have to learn over again and hope will come back. My once powerful legs grew spindly, the left one more frail than the right, and I tottered through loss of balance. When the lights are out, my eyes can’t tell my legs what to do. Even with the support of a cane, if I try to walk through a dark room, I’ll fall on my face.

Damaged nerves still locked in the swath of scar tissue send cockeyed impulses to my brain. My brain can’t make any sense of them, so the verdict comes back: That must be pain. But I don’t hurt where the bullet went in. The pains are called neurogenic and are “referred” to my feet and legs. They come in electric surges that first roam the left leg and then the right and stop my clock about twenty times a day, the one time I counted. The worst variety, which occurs only occasionally, feels like a firecracker going off inside my left thigh. Another kind so numbs the bottoms of my feet that in a car I sometimes can’t distinguish between the brake and the gas.

The most effective drug, which was initially developed and tested to ward off seizures, is called Neurontin. All the others I’ve tried either are so-so or entirely miss the point. The most humiliating one was methadone, which is also dispensed to heroin addicts during withdrawal. It did me no good, and Dorothy put a quick halt to that with an urgent observation that one night among friends I was all but slavering in my doze at a dinner party.

I could still go to the gym, lean the cane against the wall, wrap my hands, see my old friends, forget it all for an hour or two, and make the heavy bags pop. I even sparred a couple of times, with a kind and nimble gentleman of my years, to see if I could do it. (My footwork is, well, shot.) Dorothy and I went back to Mexico City once because I was writing a book about what happened (The Bullet Meant for Me). The surgeon who had stopped my perilous internal bleeding and then been so kind to her and Lila invited us to join a celebration of a baptism and the confirmation of his children. He said I had to get more help, the toll was wearing me down, he could see it in my eyes.

In fast succession two more lucky breaks came my way. My car was equipped with, and I was trained to use, a simple set of hand controls, thanks to the Texas Department of Assistive and Rehabilitative Services. (Bless their hearts. Who comes up with these tongue-twisting names of government agencies?) The officer at the Department of Public Safety who directed my volunteer driving test seemed a bit puzzled, having never been asked to do that before. She waived parallel parking but at once subjected me to the fierce traffic of one of Austin’s notorious freeway construction zones. “You are well trained,” she said and, with a curt handshake and a smile, gave me back my mobility.

Then, in the fall of 2006, I was writing a magazine piece about a famous neurosurgeon at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center who had been diagnosed with the dreaded kind of brain cancer he had helped his patients battle against throughout his career (“Physician, Heal Thyself,” December 2006). He was making himself the test case for a novel combination of therapies that showed great promise and would expand clinical research, to the benefit of other victims of the disease (sadly, he died two months ago). He was also an international authority on the treatment of pain. He exhausted me one day as I followed him on his rounds and observed a surgery. We talked and e-mailed until I had some grasp of the science of his undertaking. At the end of the last follow-up interview, I thanked him and said he’d next be hearing from a rigorous fact checker (who on that story happened to be none other than Dave, the one who’d weathered the outrage in Mexico City and given me that cane).

“Wait,” said the brave doctor, as I was about to hang up. “What can I do for you?”

I hesitated. “Well, this is about you. It’s not about me.”

“No. Tell me what’s going on.”

And so, over the course of several months, with the enthusiastic endorsement of my Austin physicians, I became the patient of that doctor and of his partner in most surgeries, an anesthesiologist who is also an acclaimed specialist in the treatment of pain. One morning in November 2006 they walked out to Dorothy wearing their scrubs and beaming smiles. Using a kind of anesthetic that enabled them to bring me back to consciousness during surgery and tell them what I was feeling in the most delicate part of the operation, they had found the “sweet spot”—about the size of a dime—where they connected the leads of a neurostimulator. An innovation resulting from decades of pacemaker research, it is an implant attached to nerve systems coming out of the spinal cord. The gizmo, as I now call it, doesn’t eliminate the rogue pains—I still dread whatever sets off the firecrackers—but its electronic impulses defuse many of them. They come and go without my being so consumed by them.

In the past year many people have told me that I’m steadier on my feet, that I take more confident strides. At first I supposed they were just being kind; I still think of myself as a stumblebum. The implant high in my right hip is about the size of the women’s cigarette cases that you see in old movies. At a recent party we encountered some friends who didn’t know about the new development.

“You can feel it,” said Dorothy.

“Where?” asked one of our friends, then she laughed. “I’m feeling you up.”

“Here,” I offered, taking her hand. “Let me help you.”

About Dave’s cane. The milagro long ago worked loose from the tacks and fell away, doubtless thanks to my constantly dropping the cane with a sharp clatter. (Try tossing one from your right to your left hand and catching it so that you can shake hands with someone. I’m good at it, but sometimes I fumble.) It made no sense to award myself a replacement milagro. I sanded and restained the cane periodically, bought a new rubber foot when the old one wore through. Twice I lost it in my usual supermarket. Red-faced and grateful to some other shopper and the lost-and-found department, I was able to retrieve it.

Last fall, after a wonderful vacation with friends at a rented villa outside Lucca, in Tuscany, Dorothy and I were preparing to turn in a car at the airport in the underrated city of Pisa, where the elegant tower leans. It was Sunday, and though gasoline was readily available, on this day the stations were all self-service. Our travel agent had cautioned us that if we failed to bring our rental car back with a full tank of gas, we would be charged but that filling up in Italy is complicated. You have to estimate the amount you need in liters, calculate how many euros that will require, and feed the pump with cash (receiving no change). When you reach the amount entered, the pump shuts off. By rules of anarchy, it seems to me, if you miss your estimate, you have to circle back to the end of the line. At the station a host of couples and families were also road-weary and eager to turn in their cars. There were shouts and curses in languages I couldn’t begin to identify. Why we all didn’t take our gouging from the rental car company, I can’t imagine. With Dorothy driving and puzzling over how many euros to feed the contraption and with me wrestling the hose and nozzle, we at last filled up our little car, and with grins of love and teamwork, we took off.

And that’s where I lost my treasured cane—hooked on a gas pump in Italy. I hope whoever found it there was entertained by the possibilities.