As a freshman at Texas Tech University in 1963 and 1964, I had an afternoon job in the Student Union print shop, mimeographing various newsletters and bulletins and printing posters for authorized student events. That fall I was assigned to copy a songbook for the school’s Inter-Fraternity Council. Among the songs were several ditties with lyrics like:

Oh, you can shoot them to the moon,

But we’ll never pledge a coon.

You can put them on a bus,

But they’ll never ride with us.

Oh, there will never be a nigger

In Sigma Phi Naught.

I can’t remember the specific fraternity, but I recoiled at what I was supposed to print. I considered myself a good American and a good Democrat. It seemed that if I printed the songbook, that would make me “a good German” instead.

I told the secretaries at the office that I refused to produce the book. They passed me on to a male figure, maybe the dean, who lectured me about an employee’s duty to carry out tasks. I worried that I would lose my job, but I was adamant. After a few days, I learned that he wasn’t going to fire me.

In the meantime, I did worse. I printed out a few copies and sent them to the Lubbock NAACP. I may have also printed some lyrics in the newsletter of the Young Democrats, which I believe I edited. In any case, the NAACP complained and an item got into the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal—and promptly every fraternity on campus knew my name.

A few days later some of the Greeks encircled me in the dining room of our dorm. They started singing a song about Billy Graham and how he was a “nigger lover.” I threw one of the S.O.B.’s onto a table and rushed out. They did not pursue.

I lived in a second-floor corner room, with big windows on both sides. By the spring, frats and sometimes “cowboys,” or ag students, would gather late at night and toss empty beer bottles up. The panes of glass came crashing in as shards. One night my tormentors broke into the room, threw all of my books out of a window (books, notice!), and set the door on fire. Then the late-night phone calls started. The caller often identified himself as “Aunt Jemima.” He talked in a fake-auntie voice. I usually hung up, and he usually called back.

On a Saturday night toward the end of the spring semester, I was walking down a hallway of the dorm. Passing an open doorway, I saw my telephone number written on a wall. It was “Aunt Jemima’s” room. The aunt turned out to be a country boy like me. He was drunken and groggy, unable to rise for an assault. He told me that he was flunking out, defeated by the world of competition and the illusions of Saturday-night escape. After we chatted awhile, I decided that I was mainly a victim of his nonracial frustrations. We didn’t part as friends, it’s true, though I learned that some of my tormentors were possibly human.

But I am still not sure about the fraternity boys. Or the adults who were bureaucrats. At the end of the year the faceless lords of student housing sent me a bill for the glass. They said that if I hadn’t been controversial, then nobody would have thrown bottles at my windows. They also said that if I didn’t pay their bill, I couldn’t re-enroll.

I didn’t pay that bill. Instead, I decided that I was going to UT, today’s University of Texas at Austin, and after I made my getaway, I found that UT was a better place. Student radicals there were numerous, and I was no longer alone.

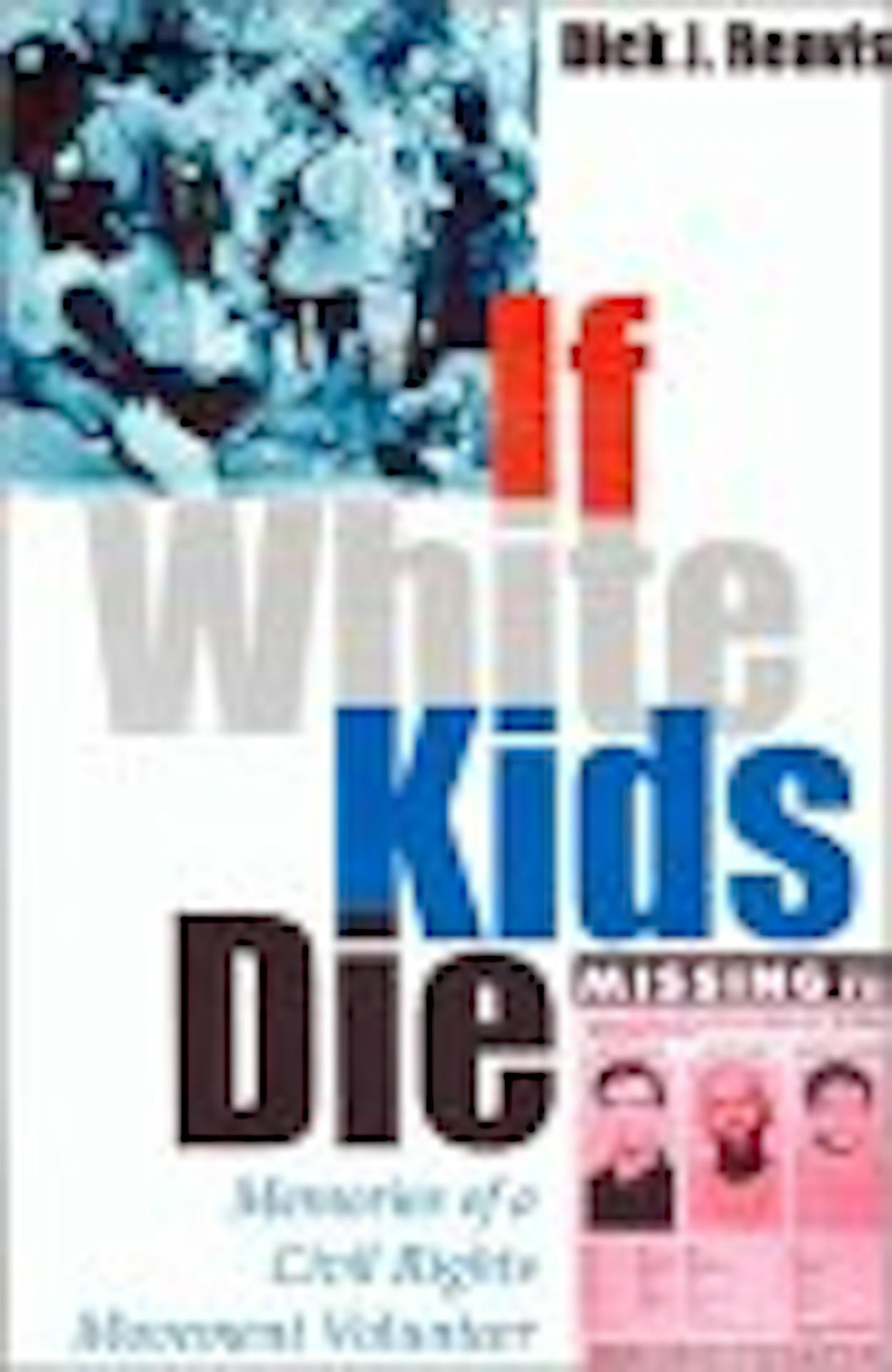

If White Kids Die (University of North Texas Press), a memoir of the time Reavis spent in Alabama as a civil rights worker, was just published.