ON THE NIGHT OF DECEMBER 17, 1998, I clung precariously to life, sanity, and a sheer cliffside overlooking an angry sea. My only companions were lizards, iguanas, and the pale light of the Mexican moon shining like a white, luminous buttock in the mariachi sky. I’d been staying just outside Cabo San Lucas at the mansion of my friend John McCall, had taken a solitary predinner power walk on the beach, and had been swept out into the ocean by a freak wave. The undertow, which killed a person that same night, swept me hundreds of yards away from the beach and deposited me at the base of a steep cliff. I tried to scramble up, but I found myself trapped between the tide and the darkness. As the water pounded ever higher along the black, crumbling landscape, intimations of mortality flooded my fevered brain. Like Arafat after his plane crash in the desert, I vowed to be a different kind of person if I survived. I thought of my mother and my cat, both of whom had gone to Jesus. I realized that I might now be seeing them sooner rather than later.

I also thought of what a bothersome housepest I’d turned out to be for my generous host, John McCall. McCall, who is also known as the Shampoo King from Dripping Springs, could afford to be generous. He runs the beauty supply company Armstrong McCall and, as he once told me, is a “centimillionaire.” For those of us who can’t count that high, it means McCall is worth a hundred million dollars. Even with inflation, that’s not too bad. “Shampoo,” says McCall, “makes people feel good about themselves.”

As I held on desperately to the cliff, I took some comfort in knowing that McCall had more money than God. There was no way, I figured, he would allow his favorite Jewboy to die an untimely death without launching a land, air, and sea search. As I shivered in the darkness, I listened for helicopters that never came and resolved that if McCall wasn’t thinking of me, I would think of him, thereby goosing him into action.

I thought of how McCall had been through hell a couple of times and come out laughing at the devil. In 1990 he himself had almost gone belly-up. Medical experts diagnosed him with deadly lymphoma and pointed the bone at him, giving him only weeks to live. Yet incredibly, McCall had a dream aboard an airplane in which the cancer turned to water and disappeared. When he went in for his next examination, the cancer was, in fact, gone. The doctors had never seen anything like it, but of course, that’s what they usually say. Either that or you’ll never walk again. McCall did, indeed, beat the first cancer, and when it returned years later, he beat it again. In the interval, just to keep in practice, he survived a plane crash in Alaska.

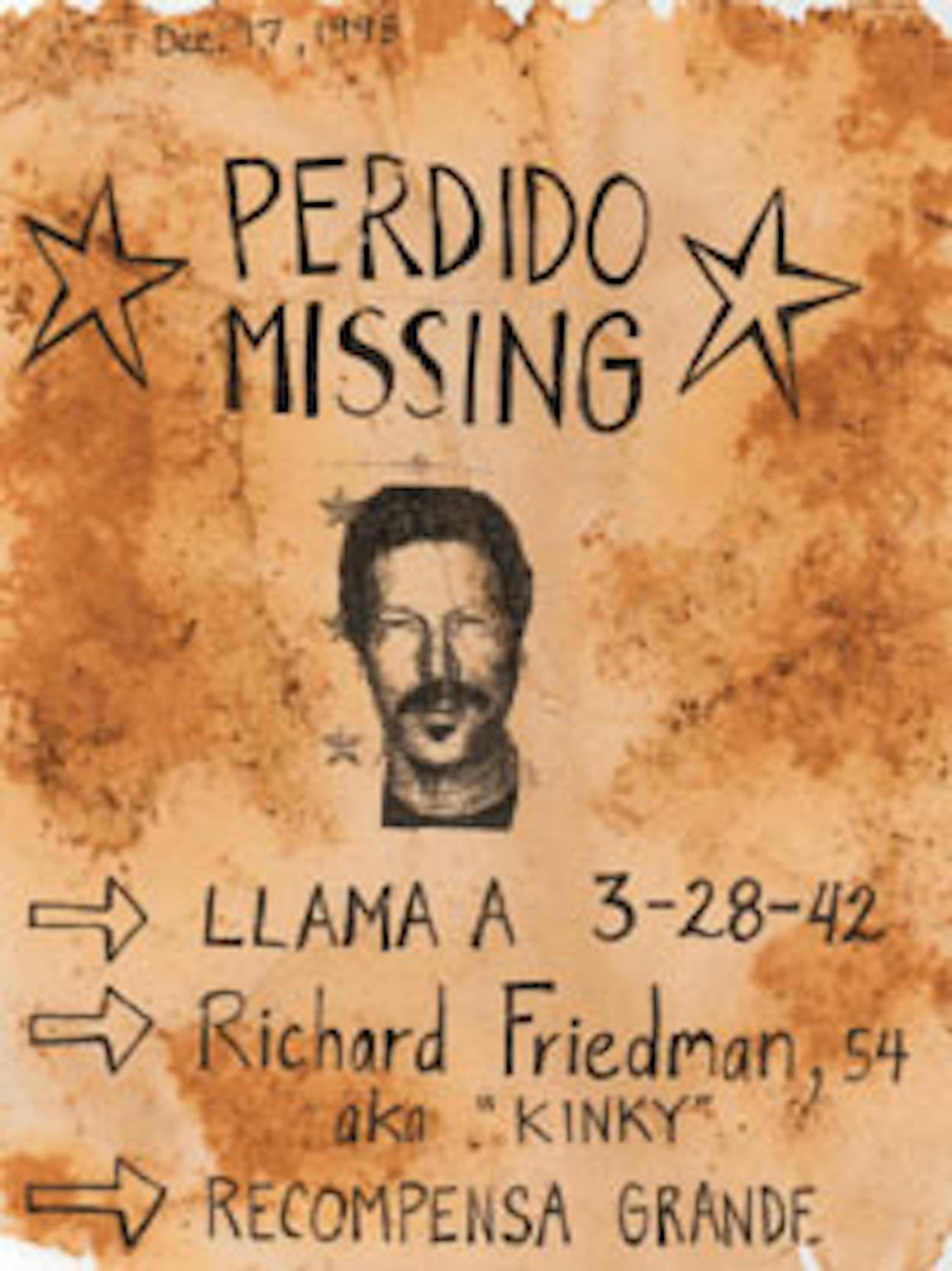

Now, as I clung to the cliff, soaking wet and shivering in the predawn moonscape, I hoped some of McCall’s vaunted luck would rub off on me. What I didn’t know that fateful night was that McCall was not really looking for me at all. It wasn’t until later that morning, when he discovered my passport, cash, and cigars still in my luggage, that he swung into action. By this time I was dehydrated, delirious, and waving frantically to every fishing vessel I could see, many of whom waved back cheerfully or held up their catch of the day. Because I was trapped, ironically, on a private beach beneath luxury homes, they had no idea that the date on my carton was rapidly expiring. But McCall knew how to launch a major campaign. Soon the FBI, CIA, and DEA were involved, Don Imus’ private jet was standing ready in New York, PI Steve Rambam had been consulted, and a large blowup of my passport photo, which strongly resembled a Latin American drug kingpin, could be seen on flyers on every telephone pole, hotel, hospital, morgue, and whorehouse in the greater Cabo area.

I, of course, knew none of this. I just kept concentrating on McCall, hoping I was getting through. I visualized a world traveler with a large wad of cash he calls “whip-out.” I pictured a mysterious magnate who happily worked as a roadie selling T-shirts on my recent concert tour of Europe. A man who makes huge donations to worthy causes almost always under the name Anonymous. A man who invites the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders to his birthday parties, which he often doesn’t attend himself. A man with a gazillion-dollar home outside Austin that is known as the Taj McCall. Yet money, I reflected, never seems to make people happy. As McCall himself once told me, “Happiness is a moving target.”

Late in the afternoon, my hopes were fading. If I survived, I vowed, they could give me a goat’s head and I’d dance all night. Once again I began stumbling upward, lost in the rocky landscape, trying to find a way to the top of my upscale death trap. Suddenly, while climbing a steep ledge, I was miraculously plucked from my precipice by an intrepid band of Mexicans who were rappelling downward. They had been working on Sly Stallone’s house, and McCall had commandeered them. Fortunately, they knew exactly where to look: The same thing had happened to another person just weeks earlier. Sly was not home at the time, but McCall was waiting at the top with a warm hug and cold cerveza. To paraphrase my father, it felt almost good to be alive.

That night, after ocho tequilas, I asked McCall what took him so long. He explained that he didn’t take my disappearance seriously at first. McCall remembered a conversation the two of us had had several years earlier when we toured the Australian Outback. We had discussed how easy it would be for a person to disappear if he wanted to. McCall, in other words, was convinced that my absence was staged, quite possibly as some kind of publicity stunt. I’d never been averse to a little publicity, of course. I just didn’t want to die from exposure.

Some days later, without pulling any punches, McCall finally revealed to me the thing that might have been the toughest blow of all. “The real tragedy,” he said, “is that you were fifteen minutes away from making CNN.”