Raising a great cloud of caliche dust, Darrell Royal zoomed away from the lake house in his van. He explained his haste as a measure of consideration for another driver behind him; by putting more distance between them, he was trying to spare the other car’s finish a cloak of biscuit colored grit. He did not, however, slow down appreciably when he reached the blacktop, which curved through cedar brakes into a bait camp on the Pedernales River, thirty miles west of Austin. Making his midday rounds, Darrell paused on the front porch of a beer joint the regulars call Mona’s Yacht Club, where he engaged the dull, cross-eyed stare of a young possum that Mona had offered him earlier, by phone, as a pet baby raccoon. Inside, Mona and her boyfriend, Sonny, made their customary small fuss over Darrell and rushed to prepare his usual with meat and double cheese. They’re proud of their clientele. Willie Nelson even brought Barbara Walters here for the taping of that strange celebrity interview. Greeted by a neighbor who had come to Mona’s to cash his Social Security check, the coach dabbed his French fries in catsup and discussed how they might bring their dusty road to the attention of Burnet County paving crews.

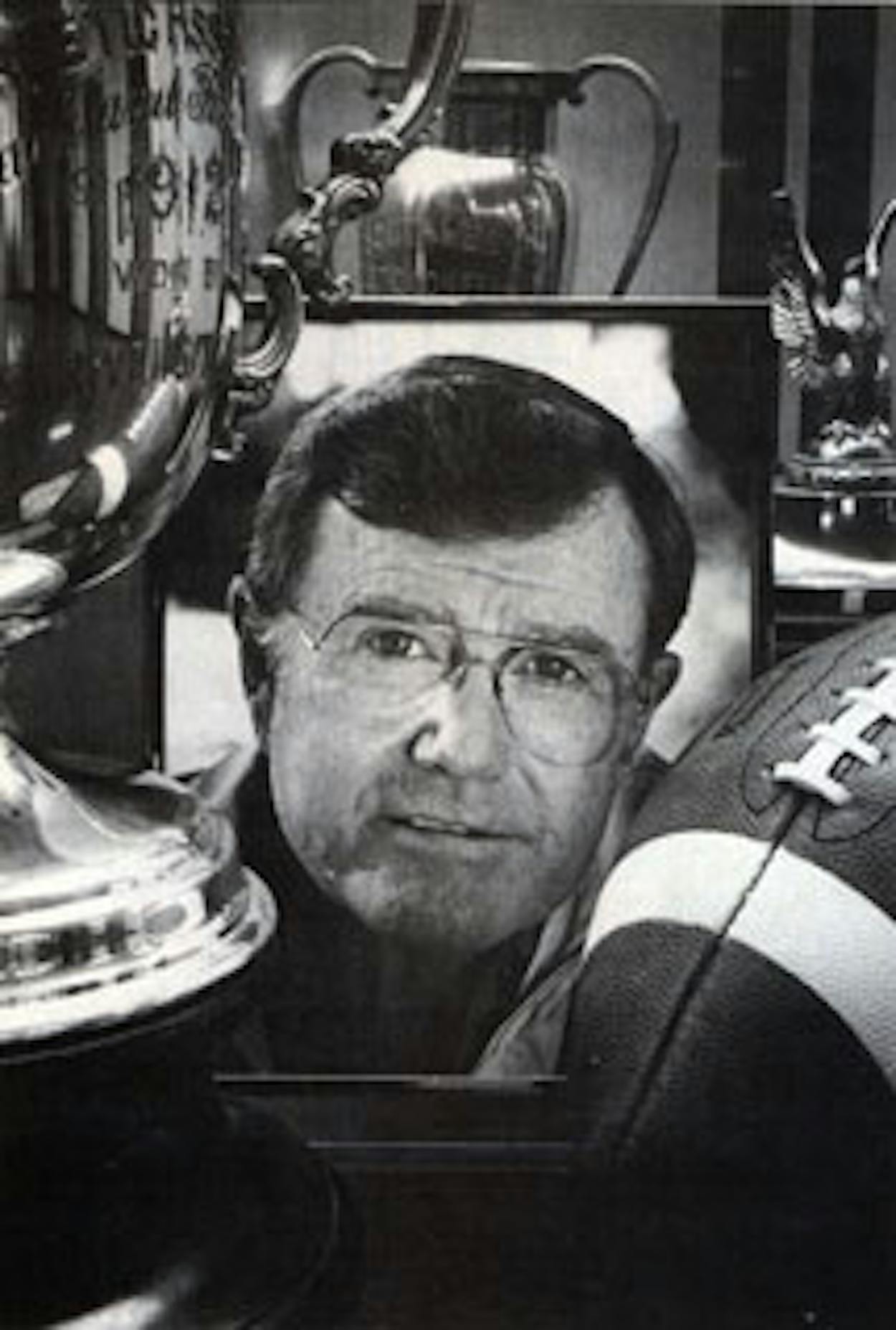

Like other retirees, Darrell Royal at 58 lives a life that is a mixture of old hurry and new leisure: attention to homey details long neglected, vague itches, snapshots of grandkids, melancholy suspicions, rounds of golf, time on his hands. He was one of the top college football coaches, of all time, but today he entertains conversation about the game with an air of polite sufferance, not nostalgia. Among Texans he was a towering figure, an establishment icon, a symbol of toughness, command, and pride. Now he cherishes most those days when he goes unrecognized except by a few bearded, grizzled, disreputable friends. The autumn years of this amiable but saddened man are a season of underlying discontent.

Down the road from Mona’s is Willie Nelson’s private country club, the salvaged asset of a failed subdivision. With a posh clubhouse, terraced swimming pools, a nine-hole golf course, and a fine view of the blue cedared hills, it’s a dream toy if you can afford the real estate. Darrell, who has played some of the best golf courses in the world, likes this one because he doesn’t have to make appointments and observe tee-off times. He just wanders over when he feels like it and scares up a game with singer Steve Fromholz, screenwriter Bud Shrake, or—when the band’s off the road—the head man himself. “Willie shoots about bogey gold,” said Darrell, “though it’s hard to tell, because we don’t look for balls. We circle through the area, but if it doesn’t show up, we just drop another one. Last time, we played sixty or seventy holes. Started at ten and quit at dark.”

Sighting none of his regular companions, he detoured through the clubhouse to check in with his secretary at the university, who reported a call from Tennessee coach Johnny Majors. As special assistant to UT president Peter Flawn, Darrell advises the university—occasionally—on matters like athletic department contracts and the proper status of club sports. He travels extensively, playing in pro-am and charity golf tournaments, and still maintains his Onion Creek home and a Mercedes given to him by the Longhorn Club. He has always had the poor boy’s taste for the blandishments of the country club—the Onion Creek kind, and lately the Willie Nelson kind, too. Willie’s main clubhouse has been converted into a plush and formidably equipped recording studio. “I watched every pick of the album he cut with Roger Miller,” said Darrell, with a reverence that those of us who are football fans might have felt had we stood at the coach’s shoulder and on an extra headset during the Arkansas Shoot-out in 1969. Hanging out at the lake. Playing second fiddle to Willie and Waylon Jennings and Billy Joe Shaver.

“There were people who didn’t like it,” he acknowledged, “people who didn’t like it at all. They just couldn’t understand why the head coach at the University of Texas would want to associate with those guys. Same ones now that ask me to get Willie’s autographed picture for their grandkids. Now they want a personal introduction.” He laughed without much humor. “I’m friends with Don Williams too, and he’s straight as six o’clock. Somebody wrote in that rock magazine Crawdaddy that on occasion I’d been known to ‘widen my nose.’ I didn’t know what the hell they were talking about. I know now. But I’ve never taken one puff off a joint, never taken pills, never done any of that. Drink too much beer sometimes. I’m not around when all that’s taking place. They don’t do it when I’m there. They manage to like me in spite of my faults. And I’ve sure as shit got some chinks in my hide.”

Eighteen years ago, as the University of Texas chartered plane descended on the Austin airport, its passengers were the top-ranked college football team in the country. The Longhorns had just leveled Oklahoma 28-7 for their fifteenth consecutive win. Suddenly Darrell Royal rose from his seat and ran toward the cockpit. Moments later, at the coach’s request, the engines revived, and the plane broke its descent. The Texas players peered out, spell-bound, while the plane banked and circled back over the city for an elaborate second look at the stark spire of the university tower, with its triumphant crown of orange light.

To understand the quiet magic inside that propeller-driven plane and to appreciate Darrell royal now in early retirement, you must recall the lavish success of his working prime. During Royal’s glory years, in 1959-70, Texas’ record of wins, losses, and ties was 99-19-2. And only four of those losses were decided by more than a touchdown. Four times during that twelve-year span, Royal’s teams finished the regular season undefeated; four more times they lost just once. Seven times during those dozen years, the Longhorns were ranked number one in the polls as late as midseason. On three occasions, Texas lined up in a pairing of the country’s first- and second-ranked; Royal won every time. He won 12 of his first 13 games against Oklahoma. His career tally with the aggies was 17 wins out of 20 games. Even more remarkable since Frank Broyles’ teams still hold up on – on paper – as the Longhorns’ equal, Royal closed out his career 15-5 against Arkansas.

You have to go back thirty years to his mentor, Bud Wilkinson, to find another coach who so thoroughly dominated the profession. In the sixties, Royal’s competitive edge and captivating style effectively symbolized that profession. If the bedeviled genius of Vince Lombardi epitomized NFL coaching in those years, Darrell was taking care of the undergrads down home. Few college teams have ever been such a reflection of the head coach. Royal acted more like a small-town banker than a football coach, and his boys acted more like future small-town bankers than future pro stars. He could be comfortable at the country club or the rodeo, and his football team was the same way. It was tough and earthy and physical, but it was also beautifully polished. The Longhorns never came out for games jumping up and down on the sidelines. They didn’t spike the ball or high-five or dance around like cheerleaders after sacking the quarterback. Royal would have dropped dead before he put little decals on players’ helmets as rewards for their effort. His players acted as though they expected to win, and they usually did. For twenty years, his aphorisms and boyish grin pervaded the region’s consciousness. His TV show, cohosted by humorist Cactus Pryor, went beyond the usual humdrum of highlight films and the next week’s predictions with its Johnny Carson-Ed McMahon type of banter. Among Texans, only Lyndon Johnson had more nationwide visibility —and Royal certainly had the higher popularity rating. In Austin, sycophants of a conservative bent were particularly fond of citing his attributes as a potential gubernatorial candidate, but Royal was never tempted. Bud Wilkinson’s post-retirement campaign for the US Senate in Oklahoma demonstrated the illusions of politics, and his prodigy was secure in his own realm. In those days, country musicians like Willie Nelson clamored for a crumb of Royal’s public attention. Royal hammed it up on camera with Bob Hope, and his lifelong hero, General Douglas MacArthur, hosted a banquet in New York in the coach’s honor. Richard Nixon squeezed in for a share of the sweat and celebration in the Texas dressing room. Within the considerable boundaries of his profession’s domain, Royal was king.

He was there when the modern beast dragged its pads out of the swamp. When Darrell Royal played for Bud Wilkinson at Oklahoma in the late forties, Bobby Layne and Tom Landry lined up in the backfield for Texas. Curt Gowdy was a sportscaster for Koma in Oklahoma City. Texas Schramm was a sportswriter for the Austin American-Statesman. Royal was the kind of player he later loved to recruit: a fast, undersized halfback converted to a quarterback because of his feel for the fake, read, and pitch of the option, a sprint-out passer equally at home in the defensive secondary. During his two years at quarterback, he completed 54 percent of his passes and threw 76 times in one stretch without an interception. On defense he set an Oklahoma record for career interceptions and once ran down a 9.5 sprinter from behind. He set other OU records with an 81-yard punt and a 95-yard punt return. In a 1947 upset of Missouri, he punted out of bounds on the one-, three-, and four-yard lines.

As a coach, Royal’s approach to football was thoroughly consistent with those origins. Field position, the kicking game. Control the line of scrimmage and make the other guy pass. His one major tactical innovation, the wishbone triple option, was simply a refinement of Wilkinson’s split T. His typical quarterbacks at Texas – Duke Carlisle, Jim Hudson, Bill Bradley, James Street, Eddie Phillips, Alan Lowry, Marty Akins – were mirror images of himself.

The charming Okie with a dimple in his chin was college coaching’s golden boy. Eight jobs in eight years, 1950 to 1957, family in tow. Brilliant lectures on the split T at major coaching clinics. At 28, the first job as head coach, with Edmonton, in the Canadian pro league. But Royal always thought the pro game was superfluous, a bit tawdry. At Mississippi State, the next stop, he further refined his views on football’s hierarchy and decided that a major state university was what he wanted.

The Texas job was a dream come true, and he was quick to make sure that it would be a dream with some longevity. His teams flirted with the national championship in 1961 and 1962, then won it in 1963 with an undefeated season and a Cotton Bowl rout of Roger Staubach’s Navy. In the early part of 1964, the athletic council of Oklahoma announced that it would like to replace the departing Wilkinson with Darrell Royal, but Royal, to the relief of orangebloods reveling in the national championship, eventually excluded himself from consideration. Two weeks later, after the athletic council and the faculty council requested that Royal be given faculty status, the regents went one better and made him a full professor with tenure, in addition to giving him a $4000 raise—a move that, to Royal’s anguish, raised howls from tenured professors all over campus. Trying in turn to keep everybody happy with him, the coach wasn’t immune to errors of judgment. He supported Ben Barnes for governor a bit too publicly and permitted the photography of his Chrysler endorsements on the floor of Memorial Stadium, forgetting that “we have a whole lot of Texas supporters who sell Chevrolets and Fords.” But in the Byzantine world of the UT System, he was a master politician. At parties under all the right chandeliers, he and his wife, Edith, would part company at the door, sip cocktails, and expertly work the room. But he never let his social access to chancellor and regent lure him outside the chain of command. He accepted nothing but phone calls from the wily and solicitous Frank Erwin, who lobbied covertly for his dismissal on occasion. “We fouled up,” Royal explains now, with a droll wink. “After about ten years, we let A&M beat us one time. Frank could be a fierce enemy on one issue and turn cartwheels for you on the next. I enjoyed watching him work.” As athletic director, Royal delegated routine administration of the other sports to two of his assistants, Bill Ellington and Jack Patterson. His game was football, the money-maker. He lodged all departmental requests with the athletic council—budgetary overseers appointed by the president from the faculty, the student body, the Longhorn Club, and the Ex-Students Association, but with a faculty majority. Royal manipulated that bunch like a smart district attorney in the grand jury room. A former member of the athletic council recalls those sessions: “I always thought I’d hate to meet him in a dark alley when I had something he wanted. One way or another, he was going to carry it off, probably with a smile on his face and with me thinking he’d just done me a huge favor.”

He always had a gift for the colorful gesture, the quotable turn of phrase. Riding the team bus toward Royal’s first win over Oklahoma, student reporters from the Daily Texan gaped: he was actually kneading an orange rabbit’s foot with his thumb. Running the wing T in the early sixties, he caught the sportswriters’ fancy with something called the flip-flop line, which was just a simplification of blocking assignments neatly lifted from the obsolete single wing. “The flip-flop gained national prominence not because of its explosive results,” said Royal, “but because its name is a form of advertising. And who says it doesn’t pay to advertise? In Colorado there are thirty mountains taller than Pike’s Peak. Name one.”

But he didn’t win thirty straight in a hall of mirrors. “The only way anybody’s ever going to beat Oklahoma,” he declared at the outset, “is to go out there and whip ‘em jaw to jaw.” The essence of football, he contended, is the wreckage of the guy directly in front of you. Royal’s antipathy to the passing game was famous: “When you pass, three things can happen, and two of them are bad.” He also observed that even the best pro passing attacks take four or five years to develop; the rapid turnover of college personnel prevented the necessary fine-tuning. But he also seems to have scorned passing because it was art, not muscle. It introduced randomness to the game. The rushing game, on the other hand, forced one-on-one confrontations, strength versus strength. By running the football, you not only defeated people, you established your physical dominance. The victims remembered. And word got around.

Before the 1963 game against Baylor, a major air-minded obstacle to his undefeated season, Royal told Sports Illustrated, “The guy with the blue serge suit with his green socks rolled down didn’t go to Texas.” He wasn’t just psyching that week’s opponent and catering to the snooty pretense of UT alums. He buried the opposition with his concept of the major state university. He surrounded himself with the best assistants he could hire, and his policy of recruiting as many good players as he could explains the NCAA’s adoption of today’s thirty-scholarship limit. In 1965 James Street, then a senior at Longview High, he was inclined to attend Arkansas because Texas already had a freshman quarterback sensation, Bill Bradley. In the Memorial Stadium press box during one of those frosh games – while “Super Bill” ran, passed, punted, and intercepted on the field—Royal casually convinced Street that competing against UT’s surplus of talent was the most important challenge he would ever meet.

Street says now that when Royal passed through his team’s locker room, a hush descended, even on the players who despised him. Direct confrontation with the head man, outside the context of athletic endeavor, was avoided at all costs. “Coach says, ‘Now James, you know it wasn’t that way. My door was always open to you guys.’ Yes, sir. Except we didn’t know what we’d get into if we went in there. One time Bradley and I went up to Dallas, riding motorcycles, and got into a little trouble. Coach Royal called us into his office, and we denied everything. ‘Now, boys, if I was going fishing, I’d just as soon do it with a coupla fellas like you. But I know for a fact you weren’t up there reading your Gideon Bible.’ I came out of there with my knees shaking. We sure never went to him for fatherly advice. If something like that came up, our man was Coach Bellard.”

In the spring of 1968, following a third consecutive 6-4 season, Royal redelegated the responsibilities of his staff in a general shake-up. The previous offense coordinator, Fred Akers, was shuffled to the defensive secondary. Moving from coaching linebackers to coaching offensive backs, Emory Bellard inherited an assignment over the summer that would change the form of college football. Royal had more great running backs—Chris Gilbert, Ted Koy, Steve Worster—than starting positions in the I formation the Longhorns would be using. Royal told Bellard he wanted a fullback-oriented option offense in which all three runners could participate. Bellard’s solution was the wishbone triple option.

In secret workouts that fall, Bradley and Street didn’t think they could run the offense. Sure enough, the fullback had to line up a couple of steps deeper to give them the time and the angle. And when Bradley still couldn’t get the hang of it, Royal grabbed Street in a losing cause at Tech: hell, you can’t do any worse; get in there.” In the tension and embarrassment surrounding Super Bill’s demotion, Bradley worked out the next week at wide receiver. Running a deep route one day, Bradley loosened the drawstring of his sweat pants. As he sprinted, the sweats slipped down over his buttocks, his thighs, and clumped around his ankles. The squad broke up in laughter, and the tension dissolved. Super Bill went on to all-pro stardom in the defensive secondary of the Philadelphia Eagles. And at Texas the thirty-game streak was underway.

The wishbone was the apotheosis of Royal’s coaching philosophy. Texas had days when all four backs ran for more than a hundred yards, when the total offense surpassed six hundred – almost all of it on the ground. But all great coaches are prepared for the day when the game plan doesn’t work out. Riding the bus to the stadium for the 1969 Arkansas Shoot-out, the game for the national title, Royal sat down beside street and told him to run a quarterback option to the left if the time came for a 2-point conversion. “Aw, Coach,” drawled Street, discounting the possibility. “I’m just telling you,” said Royal. A lesson learned from the first 15-14 win over Oklahoma in 1958 and the 14-13 loss to Arkansas in 1964: if you have to score twice to win, go for 2 after the first touchdown.

But before the 1969 Longhorns could claim their 15-14 triumph, they had to get past fourth and three at the Arkansas 43 with 4:47 remaining – and they did it with Royal’s famous riverboat gamble, 53 Veer Pass. “WE were on the sideline on the phone to Coach Bellard, talking about overshifts,” says Street. “Coach Royal just snatched that call out of the air. I questioned the formation more than the play. The tight end, Randy Peschel, was the only receiver on that side of the field. In the huddle I couldn’t even look at him. I acted like I was talking to the split end, Cotton Speyrer, hoping Arkansas would think I was throwing it to him. I said, ‘Peschel, I don’t care what you do. Run down there, turn around, and come back at me; just get open.’ And then when I let it go long, I thought, ‘Oh me, what if he actually does that? What am I gonna tell Coach Royal?’

“No coach in his right mind would have made that call!” laughs Street, who clearly loves the man. “But it worked.”

The lake house is remarkable for its lack of athletic memorabilia. A few sports titles on the bookshelf, a snapshot of Earl Campbell in a cowboy hat, his arms around the Royal’s grandchildren, but scarcely another clue. We sat talking about the Jackie Sherrill debacle in College Station. Darrell watched a pair of cardinals raid a birdfeeder on the deck. “You may not have seen yesterday’s paper,” Edith was saying. “Jackie said if he had to do it over again, he’d still be in Pittsburgh.”

Darrell set his coffee aside with an only-the-Aggies stretch of the mouth. “They didn’t have to go public with that. You keep the coach’s salary in line with the deans at the university. Then if you want to do a little something extra on the side, that’s fine, that’s private business. But to come right out and publish the figure, that just puts Jackie in a bad spot with the faculty. Jackie Sherrill’s a nice guy. He’s not overpaid.” Darrel chuckled. “They’ll make him earn every penny.”

The phone rang, and he spoke briefly with Pat Culpepper, his onetime linebacker, team captain, and staff assistant, now a high school coach in Midland. Culpepper was from Cleburne, which contributed a disproportionate number of top players during Royal’s early years – Timmy Doerr, David McWilliams, Howard Goad, and Fred Sarchet. They were the kind of players Darrell favored: small-town kids who believed in the program and toed the coaches’ line. As a UT assistant, Culpepper also played a prominent role in Gary Shaw’s Meat on the Hoof, the 1972 book that kicked the first large dent in Darrell’s expertly chiseled public image. Shaw, a reserve guard in the mid-sixties, portrayed Culpepper as a screaming fanatic in charge of the brutal “shit drills” designed to discipline uncooperative players and chase off others whose scholarships were needed for the next class of recruits. Culpepper has since compiled his own version of the Royal years, and that was the purpose of his call. Darrell told him he’d be glad to read the manuscript.

Shaw portrayed “Daddy D” as a man who could stand over a talent like George Sauer when he was writhing on the ground with a knee injury and, completely detached, finish eating a hamburger. And Sauer was a gate attraction and the son of an old friend. “Coach Royal met my parents once when I was being recruited as a freshman,” Shaw wrote. “Four years later he ran into them after a football game and immediately called them by their first names. Three years after I was gone and a full seven years after meeting them, Royal met them again at the Denton Country Club. Again, without hesitation, he addressed them by their first names. Maybe, you say, he just has a memory for names and faces. Yet two years after I’d played for him for your years I ran into him on campus and he couldn’t recall mine. A player that has come and gone and has no PR value is a different case.” Meat on the Hoof drew blood, and the coach didn’t respond kindly. “Shaw says he took psychiatric treatment when he was here,” Royal said at the time. “That’s kind of common these days – but I have never felt the need to go take treatment.” He has since mellowed on the subject. And give him credit: he at least read the book. Tom Landry is never going to turn a page of North Dallas Forty.

“I don’t deny at all that we ran a tough program, especially back then,” said Darrell. “I don’t think we ran it without feelings. But for Gary it was a real powerful experience, and I think he was entirely truthful in ninety-five percent of that book, as he saw it. I still object to the five percent lies. I didn’t even recognize some of those drills he described. We never had them – ever, at any time. But there’s not much in that book that wasn’t true.”

There was some hurt in his voice. “Gary said I ran into him on campus and didn’t even know him. Well, the guy grew a beard and long hair and lost down to a hundred and seventy pounds. Quite possibly I’m guilty of that. But I’d have recognized him if he still had a crew cut and weight two hundred. I remember the way his legs were built, the way he moved…”

Edith laughed. “Darrell’s the only person I know who recognizes people by their legs instead of their faces.”

He wagged his head and smiled, momentarily nonplussed. “They never did need numbers,” he said. “I know that.”

Darrell Royal’s first fifteen years at Texas produces twelve bowl games, two undisputed national titles, and unquestioned mastery of a strong Southwest Conference. Not bad for an old boy who never wanted to do anything but coach football. But it all began to go sour for him in 1972. Meat on the Hoof hit the stores in the middle of the season, and the weak before the TCU game the Associated Press ran a five-part series on lingering racism in the UT athletic program. By then Royal had six black players, and he authorized their interviews with a fair amount of confidence. One of the AP reporters, Jack Keeer, says now that Royal, who gave much of his own time to the project, seemed almost relieved to have the issue aired. Still, he was hardly prepared for what his players had to say. Even Royal’s All-American fullback, Roosevelt Leaks, believed he felt the sullen pressure of bigotry – from the white players, from the coaching staff, from the university at large. (Now with the Buffalo Bills, Leaks still wonders if the knee injury he suffered in the spring of 1964—which converted his dreams of big-money NFL stardom into the marginality of being a fifth-round draft choice, followed by a journeyman career as a blocking back and short-yardage plugger—was not an ill-timed accident, as it was popularly supposed.)

Royal’s attitude was a complex and contradictory blend of generous instinct and redneck, fundamentalist, Dust Bowl origins. As a child in California, he was branded and humiliated by the Okie epithet, and the experience was reflected in his racial outlook. But his sympathy for the outcast never undercut his esteem for the country club. In 1953, as coach of the Edmonton Eskimos, Royal tongue-lashed his white players for their racist invective. He and Edith befriended the black pros, helping to ease their Canadian isolation. While at Texas, he quietly served as trustee of Stillman University, a school for blacks in Tuscaloosa. Yet he hardly championed their cause on campus in Austin. Even after the program was officially integrated in 1965, he didn’t wear out many shoes in active recruitment of blacks. One past delegate on the athletic council contends that the policy was stated, not tacit. But the same delegate acknowledges that on one on the council raised a word of protest. Certain elements of the university power structure – people who had a good deal of say in the hiring and firing of football coaches—made no bones about their racist intent. Royal wasn’t about to walk that plank.

As a coach, he was no fool; he could see what blacks had brought to the game. At the same time, he seemed to question the discipline and preparation of black players—particularly those from inner-city school districts. He wanted solid citizens in his program, not freelancers. Suffice it to say that in his position, with his own power base, he could have done more for blacks than he chose to. But in the context of the AP series, it mattered little how much he had or hadn’t grown in personal outlook. The damage to his professional reputation was done. His career crowning achievement, the great wishbone machine of 1969, was remembered—and denigrated—as the last lily-white national championship team. To hear rival recruiters tell it, he was George Wallace in the schoolhouse door.

To the parents of potential recruits, Royal also had to explain the prevalence in Austin of certain alternative lifestyle—an especially sensitive subject for him. His own children sampled the exotic fruit available to Austin’s upper middle class. Marian, divorced from Chic Kazen, a lawyer and son of the Laredo congressman, liked to hand out at the hippie rock emporium Armadillo World Headquarters. She was a painter of strange abstracts, psychedelic butterflies; one of her major works was the mural in the ladies’ room at the Armadillo. The middle child, Mack, tried to place his photographs in local art galleries, but to friends he was withdrawn, prone to spending long hours in front of the TV with stereo headphones clamped over his ears, shutting the world out. The youngest, David, studied guitar in 1972-73 at the Berklee School of Music in Boston. They were bright kids, adored by their friends, totally without direction. The focus of their rebellion—if that’s what it was—seems to have been a rejection of their parents’ all-consuming, single-minded purpose. They weren’t particularly bothered by thoughts of a career.

At home, few family snapshots included a likeness of dad. He was always tied up at the office and on the practice field, busy being the coach. Then, in March 1973—the first recruiting season after the AP series and Meat on the Hoof—a university shuttle bus demolished a car occupied by Marian and her two children. The children survived their injuries, but Marian lay in a coma, and royal had twenty long days to think about what he had missed in his pursuit of professional fulfillment. After she died, he went one night by the Armadillo—to make a little peace, to try and understand. As a fixture of the establishment, he wasn’t received too kindly. Vandals took his spark plug wires, and later, in the parking lot, somebody tried to hand him a joint. Sportswriters on the Longhorn beat say the coach was never quite the same after Marian died.

Even under the best circumstances, Royal felt demeaned by the circus of recruiting. He was too proud and intelligent a man to grovel gladly at the feet of seventeen-year-olds. In 1974 he told the story of a sought-after lad who informed the head coach at the University of Texas that he, the coach, was sitting in the recruit’s favorite chair. “Well, unfortunately, I was so taken off guard—I should have more poise than that—I just moved over like a little poodle dog.” Royal’s model All-American was a guy like James Saxton, who hung up his pads after graduating and blended into the Austin community as a bank executive. But by the seventies the top recruits looked on college as a farm system for the pros. And the recruiting grind meant countless explanations of Austin’s hippies, Meat on the Hoof, and the coach’s alleged racism. In recruiting blacks, Royal wasn’t just paying lip service to the cause of social progress. The college game was evolving toward the pro variety—toward size, specialty, and most of all, speed. He had to have blacks in order to win.

Royal could vacation in Jamaica with country singer Charley Pride and swap yarns with Earl Campbell’s mom. They had everything in common except the color of their skin. But he never felt at home in the ghetto. His noteworthy black recruits, like his white stars, were from small towns: Leaks from Brenham, Campbell from Tyler, Johnny “Lam” Jones from Lampasas. Campbell, a rarity who narrowed his original list to Texas, OU, Houston, and Baylor, and then told other recruiters not to bother, was the vindication of Royal’s approach. Yet Woodie Shepard may have left the stronger taste in his mouth. Informed by an assistant coach that Shepard desired the presence of the head man when he signed the letter of intent, Royal finished a speaking engagement in Harlingen and flew to Odessa by private plane for the ceremony. “And then we can’t even find him,” Royal remembers, still fuming. “Can’t even talk to him on the phone! We stayed up all night long trying to find that guy.” Where was the elusive prospect? “Hiding out—from us—with Oklahoma,” says Royal, through clenched teeth.

Barry Switzer of Oklahoma didn’t curry Royal’s favor by beating him five straight times with the wishbone, aid in 1975 he suggested that the careers of some coaches faltered because they spent too much time listening to guitar players. “I know exactly why we had so much recruiting success, “crowed Switzer. “We outwork ‘em. I’m young. My staff is young. Our hair is still growing. We can jive with the kids, dance with them.” Toward the end, the cavalier recruiting ethics within his profession, particularly among Switzer’s crowd in Norman, became an obsession with Royal. He even talked about working as an investigator for the NCAA after he retired.

Switzer was the only opponent who ever baited him successfully. In more ways than one, OU had his number. The week before the 1976 Oklahoma game, Royal claimed that his staff had apprehended an OU spy in Memorial Stadium during a closed Longhorn workout. In the ensuing black comedy, Royal challenged Switzer, an OU assistant, and the alleged spy to take polygraph tests, offered them each $10,000 in cash if they could pass, and let slip to an AP reported his assessment of the Norman crowd as a lot of “sorry bastards.” Switzer just baited him more. “This is Secret Agent Aught-aught-six,” he told Blackie Sherrod of the Dallas Times Herald. “Six, because we’re fixing to strap it on them for the sixth straight year.” But Switzer didn’t appreciate the name-calling. “Listen, I don’t care what Darrell Royal thinks of me,” he told Sherrod. “Let him think Oklahoma all the time. Let him look for ghosts.” OU fans outside Royal’s Dallas motel room kept him awake with a chant of “Sorry bastard, sorry bastard.” They booed their onetime All-American quarterback and taunted him with the same chant in the Cotton Bowl the next day. Thanks to a brilliant game plan drawn up by defensive coordinator Mike Campbell, Royal’s team played the more talented Sooners off their feet. They had a shutout in their grasp, but then a Texas back fumbled; Oklahoma capitalized, then botched the extra point. Nobody went home happy with the 6-6 tie. Least of all Royal, whom a photographer caught stooped over with the dry heaves.

That may have been the breaking point, but Royal didn’t make up his mind until two weeks later. Recovering from a hamstring pull, Campbell got off quick against Tech on national TV—65 yards for the first seven carries—then pulled the other hamstring. Tech won the game, Campbell was out for most of the season, and on the way back to Austin that night, Royal told UT chancellor Charles LeMaistre that he was through. Despite the drudgery of that crippled, break-even season, most friends assumed his spirits would recover: “Mike Campbell begged me not to quit,” says Royal. “He said, ‘Gosh, Darrell, let’s stay through this crowd. Because they’re really going to be something.’ We know those guys could play.” But Royal announced his retirement before the season finale against Arkansas and Frank Broyles, who had said all along that ’76 would be his last year. The old friends and golfing partners played out the last installment of their great rivalry without regaining the nearly five minutes lost to a clock malfunction. Let it run. All Darrell Royal wanted from football was out.

He soon discovered that his zeal for athletic department affairs waned as soon as the games had been played. He would never be happy sitting behind a desk. As athletic director, he tried to steer the head coaching job to his friend and chief lieutenant, Mike Campbell. He lost that contest of will to regent Allan Shivers, who brought a past Royal assistant, Fred Akers, back from the head job at Wyoming. The feud between Royal and Akers was real but exaggerated. Royal rigorously stayed out of Akers’ way, and he couldn’t see that Fred had much of a bitch coming; he only inherited the potential for a Heisman trophy winner, an undefeated regular season, and a national championship if they could have won the third Notre Dame Cotton Bowl. Akers thought in turn that Royal had lobbied too vigorously against his candidacy. And when Akers represented the football program at the post cocktail parties, he found the guest lists were still drawn from Royal’s friend and loyalists.

After Royal resigned in 1980 as athletic director, he and Akers aired their differences over huevos rancheros at one of Darrel’s favorite haunts, Cisco’s Bakery. Afterward, could blithely go his way, but it hasn’t been that simple for his successor. At the beginning of this season, Akers had a better record than Royal did at the same point, but every day he feels the pressure to continue winning. He’s competing against a legend who isn’t ever going to lose another game. Akers stiffens at the mention of his former boss. “Yeah, Darrell’s a lot more relaxed now,” he says, as he clears his throat, not the least relaxed himself.

As for Darrell, although he has an office in the tower and a position as assistant to the president, he’s seldom seen on campus these days except at tapings of Austin City Limits.And often those public performances have been just an encore for Royal. For years, some of the state’s most spellbinding private concerts have taken place in his home and his hotel rooms. “Sssssst!” he would reprimand the mutterers at such events. “Listen or leave, listen or leave.” Amused, David Royal used to drift down the hall to another hotel room and away a toke of weed with Uncle Willie—before Nelson’s lung collapsed and he publicly swore off the stuff. “Hey, you guys,” David would greet his friends. “Want to meet Kristofferson tonight?”

As an athlete, David Royal never rose beyond second-string quarterback for his junior team. Which is not to say the youngest son didn’t appreciate the way his dad made a living. David loved to ride the team bus into the stadium grounds; on the sideline with the Longhorn players, he had the best seat in the house. But David’s talent lay in other fields. Though he never got around to composing tunes for his song lyrics, he had a fine ear for the acoustic guitar. After Marian died, his parents didn’t want him to return to Boston, so he enrolled off and on at UT, where he demonstrated a gift for mechanical engineering. But his interests were so scattered that he never pursued anything for long. Living in the house the Royals had bought for Marian, he accumulated junk cars in the yard and dismantled transmissions in the garage. He ceased to notice the blaring radio in the garage when he went to bed, provoking complaints from the neighbors. Exasperated, his parents told him they were going to sell the place if he didn’t clean it up.

David didn’t hold his parents’ fame against them. He accepted the surplus it sent his way. Denied access to a backstage area at one of Willie Nelson’s picnics, he convinced the security guard of his identity by presenting a Cotton Bowl watch inscribed to his dad. Nor was he tremendously impressed with his parents’ success. He groaned when his friends pestered him at the last moment for tickets to a music concert, then tried to honor their requests. In need of money to live on, he cashed in the stocks his parents had given him. He bought a motorcycle. He salvaged the restroom wall bearing his sister’s mural when the Armadillo World Headquarters was torn down. David widened his nose too often, to use Crawdaddy’s phrase. But he pulled out of that binge and told one friend that he might go to Oklahoma for a while, work the oil fields, get his head back together. Just another young man adrift in Austin.

At two-thirty one morning last March, nine years to the month after Marian had her wreck, david rode his bike around a curve just a few hundred yards from the site of his sister’s accident. There were no witnesses. He may have skidded on gravel or imprudently shifted his weight. But the motorcycle leaped the curb and crashed into a traffic sign. He died in surgery. When the devastated parents drove to his house later, they found the garage door open, radio blaring.

Larry Gatlin and performed it at David’s funeral. The grieving dad spent a long time with Gerald Mann, a Baptists preacher and chaplain of the state Senate during the last session. Several coaches, old colleagues, and competitors, came from out of town. Royal stood out in the yard with them and said he still had Mack, he still had the grandkids, he still had Edith. He still had his health. I didn’t expect you to come,” he told them. “But I’m not surprised you did.”

The deck of the lake house overlooks a cliff that divides two deep, spring-fed inlets of the Pedernales. Farther away, the river widens as it empties into Lake Travis. “We really got this place for the grandkids,” Darrell was saying. “They’re into water sports, Jet-skiing, that sort of thing. And you know how kids are. They’ll get by and see the old folks now and then, but unless you offer something in line with their interests, they get pretty busy and scarce.”

He rested his arms on the railing and said he hadn’t decided whether to remodel and expand the lake house or build another place elsewhere on the property. We’ve always managed to live moderately,” he said, “without a whole lot of money. Fortunately, we had some nice things happen for us in a business way, so I don’t guess I’ll have to go to work again. Sometimes I think about selling all that other back in town and just staying out here. This is all I need.”

I asked him why he quit coaching when he did.

“That last year, out in Lubbck,” he said, “we finally have Earl back in shape. He’s ready to go, the team’s ready to go, I feel like we’re well prepared. WE have a sell-out crowd, a national television audience. All the ingredients that should excite a coach. And I’m sitting in my hotel room thinking, “Why am I continuing to do this?”

“When I first came here, one of my friends told me, ‘if you play your politics right, you’ll have a long career.’ I told him right quick that I wasn’t a politician and didn’t intend to be a politician; I was going to coach the best I could and hope that would be acceptable. That turned out to be a naïve, immature approach. You’re just ignorant and dumb if you don’t know who the regents are and the chain of command. I also said I never wanted to be a teacher. Why, a football coach is nothing but a teacher. I had a blackboard and I was teaching the same subject over and over and over. Trying to sell an attitude that defensive players should have on the goal line or covering the kick, or how important it was to protect the kicker. Year after year after year. It was the repetition, as much as anything. I got tired of hearing my own voice. Go to a press conference after a ball game. Date back ten years and find a game of similar circumstance. Hell, it’s the same press conference. Just different names.”

He sounded angry when the subject turned to recruiting. “I don’t care if a coach is on vacation in Greece, sometime every day he’s thinking about some sophomore back home. I’ve gone on vacation and spent two or three hours a day talking to recruits on the phone. Sure, we ruin ‘em. Every year I read where the top prospects say, ‘I’ll be glad when this is all over. This is some pressure. I can’t even turn around.’ Well, Earl Campbell didn’t suffer all that pressure. He didn’t feel the need to yank all those old men around. They make appointments with you and not show up. So you think maybe he forgot, maybe his misunderstood. They keep you jangling at the end of their string. And then when it’s all over, they say, ‘I never was interested in Texas in the first place.’ I just decided I didn’t need that anymore.”

After a moment, his mood lightened. “I guess it sounds like I’m bitter about the game. I’m not. I think it can be properly administered, that the people in charge of the program can understand that it’s not just a part of the university, and not the most important part. It’s still part of education, and there’s a place for it. I had a very happy career at the University of Texas. I never felt like I was going to work, till there at the end. Edith and I were talking the other day: time for another season, and we’re ready to go out and see what the old ‘Horns can do. But I don’t miss those days much at all. I didn’t realize how much pressure I was under or how tight I was wound, until after I quit. People talk about how hard it is to climb that ladder. Let me tell you, it ain’t no easy task to stay up there when everybody’s shootin’ at your ass. My coattails were flapping all the time. I was fidgeting and moving and I didn’t even realize it. I used to say I wished they had a pill that contained all the necessary vitamins and nutrients, so I wouldn’t have to slow down and eat. I was serious at the time. I used to think everybody gagged when they brushed their teeth. And that’s in July! It’s sure hard to get by in October and November.”

He laughed and watched the wake of a boat on the otherwise placid lake. “Listen here. I don’t gag no more.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Football

- Darrell Royal

- Austin