You know by now that Deion Sanders likes to have it both ways, whether the subject is football or pizza toppings, but you might be surprised to learn of his Jekyll and Hyde personalities. Those custom-made suits, those quirky choices of jewelry and headwear, his Camptown Races high-stepping, his outrageous pronouncements to the media—that’s just Deion as Hyde, playing offense with his image. There, the issue is marketing. In real life Deion is Jekyll, the straightest, squarest guy on the Dallas Cowboys roster. He doesn’t drink, smoke, cheat on his wife, or use profanity. Though he owns a nightclub, he seldom hangs out there. Think back to the 1995 season: The two most striking images are Michael Irvin cursing the whole world on national television and Deion Sanders cradling his small daughter after the Super Bowl game. Although Deion drives a Mercedes 500SL to work, he rents a bus to take his family on vacation. Neon is glitter and gloss, but Deion is as dull as salt.

You know by now that Deion Sanders likes to have it both ways, whether the subject is football or pizza toppings, but you might be surprised to learn of his Jekyll and Hyde personalities. Those custom-made suits, those quirky choices of jewelry and headwear, his Camptown Races high-stepping, his outrageous pronouncements to the media—that’s just Deion as Hyde, playing offense with his image. There, the issue is marketing. In real life Deion is Jekyll, the straightest, squarest guy on the Dallas Cowboys roster. He doesn’t drink, smoke, cheat on his wife, or use profanity. Though he owns a nightclub, he seldom hangs out there. Think back to the 1995 season: The two most striking images are Michael Irvin cursing the whole world on national television and Deion Sanders cradling his small daughter after the Super Bowl game. Although Deion drives a Mercedes 500SL to work, he rents a bus to take his family on vacation. Neon is glitter and gloss, but Deion is as dull as salt.

“He’s two distinct personalities,” says defensive tackle Chad Hennings, himself something of a straight arrow among Cowboy miscreants. “He’s Prime Time to the public, but in the locker room he’s Deion Sanders, football player. He’s very down to earth, very approachable.” Cowboys head coach Barry Switzer agrees: “Deion is the total opposite of his public persona. He’s a dedicated, hardworking guy.” Like almost everyone else in the Cowboys organization, Switzer was apprehensive when Sanders first arrived in Dallas aboard owner Jerry Jones’s private jet, a $35 million contract in hand, diamond-studded hoops dangling from his ears, a limousine waiting to whisk him off to his suite at the Mansion on Turtle Creek. The Cowboys have had more than their share of prima donnas over the years, and many of them ended up telling it to a judge. But in a private meeting with Switzer, Deion promised that all of the Prime Time stuff was window dressing. “He told me if he ever got arrested, it would probably be for trespassing,” Switzer says with a laugh. That’s exactly what happened. A few months after Michael Irvin and his topless-dancer pals were getting hauled in for questioning on drug charges, Deion was arrested for trespassing at a restricted lake in Fort Myers, Florida, near where he grew up. He was caught with a fishing pole in his hands. Since he had been warned twice to keep away from this fishing hole, you can interpret his defiance as the act of a spoiled athlete or the weakness of a man addicted to fishing. Whatever the case, he pleaded guilty and paid his fine.

The telling Deion moment during this summer’s Cowboys training camp in Austin was a two-hour workout when several thousand fans jammed against the security fence and began yelling, “Dei-on! Dei-on! Dei-on!” If you closed your eyes, you might have believed that you were in Naples, Italy, listening to the fanatical followers of the SSC Napoli soccer club chanting for their hero Diego Maradona, but you could not fathom such an outpouring of hot-blooded emotion for a Texas athlete. Then a more extraordinary thing happened. Deion leapt the fence, threw himself into the crowd, and started signing autographs. Even more surprising than the fans’ show of love was Deion’s willingness and even eagerness to reciprocate.

“Look at that!” Emmitt Smith said, his voice full of awe. “Isn’t that something?” Emmitt was seated in the $30,000 Mercedes golf cart that Deion had brought to camp, a reminder that his Neonship spares no expense in calling attention to himself. The cart had tinted windows, a stereo system, and a mist dispenser; the vanity license plate read “Fulltime,” hailing Deion’s status as the only current pro football player to play both offense and defense. Emmitt is among a handful of active players who can begin rehearsing their Hall of Fame acceptance speeches. Deion, on the other hand, has yet to play a full NFL season. Eventually he may be recognized as one of the game’s all-time greats, but for the moment he’s all hat and no cattle.

That’s why the incident at training camp was so significant: It’s amazing that a star of Emmitt’s stature would tolerate—let alone appreciate—such immodest behavior, that he would judge Deion not for his vainglorious proclamations but for the honesty of his delivery. Indeed, every coach and player I spoke with expressed respect and admiration for Deion both as a person and as a player. You rarely hear such effusive comments, even on a team that has been successful. In a survey published last year by USA Today, NFL players named Deion the most overrated man in the league, but they also included him among the six players they wanted on their team. The point seemed to be that while his opponents are not ready to join the media in declaring Deion’s unequaled greatness, they recognize his rare talents.

Although Deion is the ultimate sports mercenary—in eight years as a pro, he has played for three football teams and three baseball teams—he has no history of creating problems in the locker room or the barroom. His only off-the-field controversy was an altercation with a security guard at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium during his baseball days. The guard filed criminal charges against Deion, but a jury acquitted him. Later, the guard filed a $1 million civil suit against the multimillionaire athlete, which seems to be de rigueur these days; but a second jury absolved him. Likewise, Deion has almost never been criticized by a teammate. After he jumped ship from San Francisco and joined the archrival Cowboys, some of the 49ers bad-mouthed him as a traitor, no doubt angered by media reports that gave him excessive credit for the team’s Super Bowl victory. In fact, Deion never said that he was San Francisco’s savior, though of course he didn’t deny it.

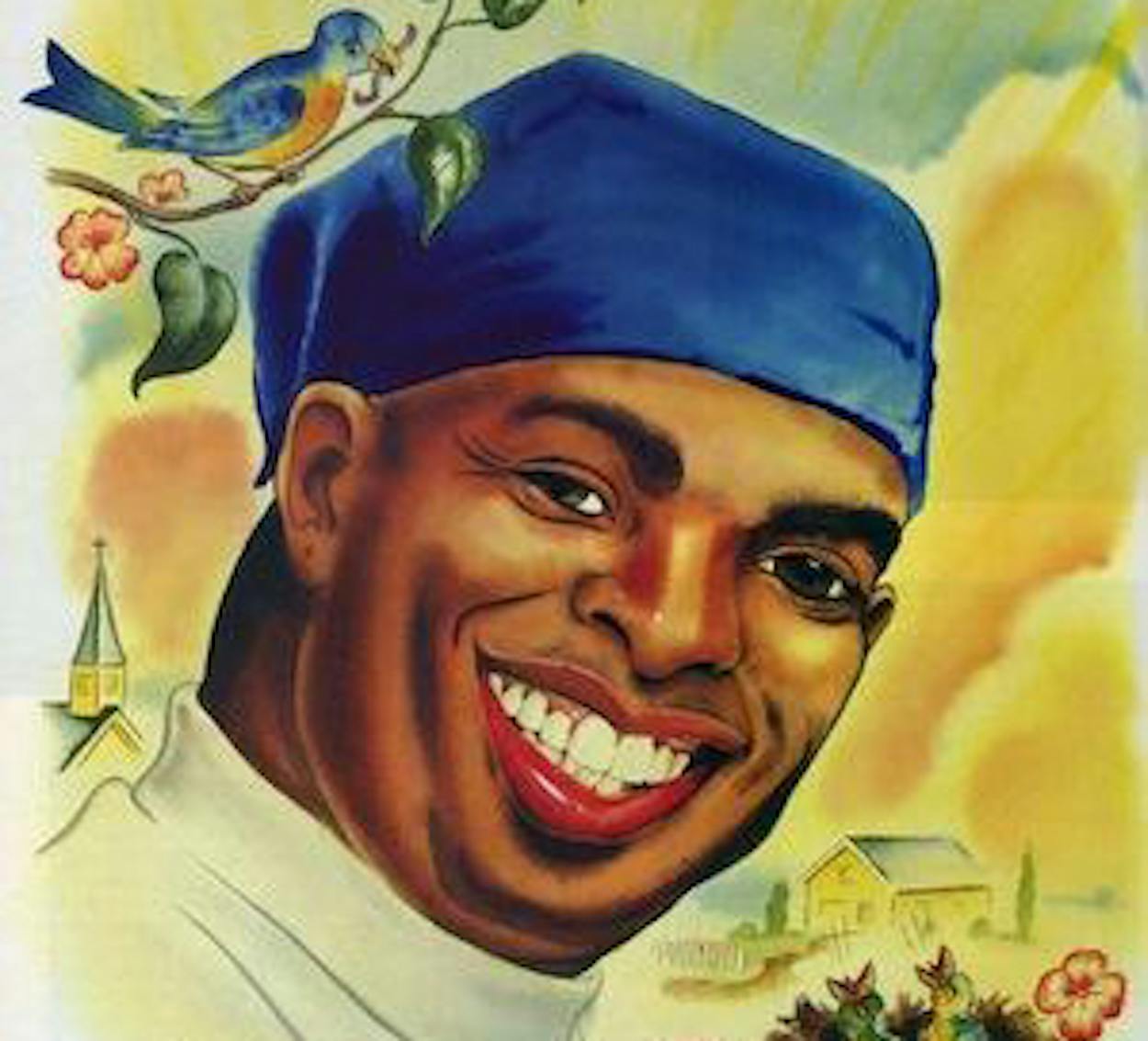

It was a shock to this longtime Cowboys observer to witness the metamorphosis from Neon to Deion. Driving from the dining hall to the dorm in his customized golf cart, he was Prime Time all the way. But as soon as he shut the door to his room, the second we were alone, Deion materialized. He slipped off his Cowboy blue do-rag and his gold Rolex, tossed them on the bed, and stretched out on his stomach like a teenager about to spend some quality time with a comic book. “I read a Bible verse every morning, and I thank God for my blessings twice a day,” he told me. “I truly know why I’m blessed with so much ability. On game day all those gold chains go, and there’s one cross around my neck.

“Who’s the real Deion Sanders, you ask?” he continued, obviously relishing the opportunity to muse on his favorite subject. “He’s a very straightforward, honest person. I have strong beliefs, strong faith, a strong character, and a strong mind. Maybe that sounds cocky, but I can’t apologize for being a very talented and bright individual.”

Deion talked about growing up in a lower-middle-class home in Fort Myers and about the powerful influence of his mother, Connie. From an early age he knew that he was special, that he was fast, quick, and graceful, that he could do things other kids couldn’t. It was his gift and he accepted it. “I don’t crave the spotlight,” he said. “I don’t need the media attention. I’ve had all that stuff since I was eight. That’s when I started high-stepping—in Pop Warner at age eight. It’s all on film!”

At Florida State University, he created the Neon persona, the here, there, and everywhere athlete who could play the first game of a baseball tournament, leave to run a leg on the sprint-relay team in his baseball pants, then return to hit the game-winning home run in the second game. Until he coined the nickname Prime Time and sold it to the media, he was just another good outfielder, another capable cornerback. He didn’t do it with mirrors; the great ability was there. But the persona was theater, make-believe, and that’s what put him on the map. As for betraying the 49ers or anyone else—well, his team-switching was just business. In the same way that the Rockefellers and Kennedys looked out for their children and their children’s children and so on, Deion made sure that the Sanders family will always be financially secure. He bought a new home for his mother. He established $5 million trust funds for his six-year-old daughter, Deiondra, and his two-year-old son, Deion, Jr. And he bought his wife, Carolyn, a $2 million house in Plano, the first home they’ve owned in eight years of marriage. (Though it did not come without evidence that the Jekyll and Hyde forces are constantly grappling for supremacy in his life. Citing his need for privacy, Deion was granted a variance from the city so that he could build a fence around his property and a gate—yet when the job was complete, he had the words “Prime Time” cut into the gate and painted bright gold.)

And Deion’s generosity extends beyond his family. He and Carolyn established the Prime Life Foundation, a charity that assists homeless families in the Dallas area. When the rap star Hammer was strapped for cash and facing bankruptcy last year, Deion came to his friend’s rescue with a $500,000 loan.

While we were talking in his dorm room, the phone rang. Deion picked it up, and I heard him say, “I can’t talk to you right now, honey. I got a man here. I’ll call you in ten minutes.” It was Deiondra checking up on Daddy. “My kids mean more to me than anything,” he told me. “I don’t care about being no All-Pro. I don’t care about no Pro Bowl, no Hall of Fame. That’s not important. What I care about is being a good father. That’s why I quit baseball—to be with my kids more, pick ’em up after school, go over their homework. I wanted to see ’em grow up, not just from time to time but every day. I didn’t want to look back in a few years and wonder who taught my daughter to tie her shoes or when my son learned to count. Those things slip by and the next thing you know, they’re teenagers.”

Deion has many irons in the fire, including a string of television commercials, a rap song he has recorded, and a movie deal, so I asked him if he could picture himself in, say, ten years. He thought for a beat, maybe two, and then said, “Yeah, I picture myself happy. My family is happy. I’m sitting in one of those sky boxes like Jerry Jones.” In the owner’s box, perhaps? Was he interested in becoming the NFL’s first black owner? “Yes, I can see that,” he admitted. “But I’d want Jerry as my business partner. He’s one of the best businessmen I’ve ever met. When we talk in private, it’s not about football—it’s about life, about investments, about future plans.”

On the field or off, Deion is a hands-on kind of guy. Though he has an agent and a business manager, he calls the shots and cuts the deals. He personally negotiated his extraordinary contract with the Cowboys: He was alone in his hotel room in Chicago after a baseball game, working his laptop, faxing his lawyer, and keeping an open phone line to Jones, who is reputed to be one of the most ruthless negotiators in sports but on that evening, at least, was just another admirer. Inthe New York Times Sunday Magazine last fall, Bruce Schoenfeld reported that Deion sometimes pitches his own ideas to company executives. “Few athletes interact directly with their sponsors,” Schoenfeld wrote, “but Sanders refuses to let a company he’s associated with decide how to use him.”

Nobody in sports has better timing than Deion. He played baseball in Atlanta at a time when the Braves were becoming unbeatable. He joined the 49ers when that team was preparing to conquer the NFL. He quit pro baseball before people discovered that he was merely average, and his subsequent commitment to football quickly had critics who saw him as a one-dimensional part-timer conceding that he could be the best one-on-one defensive back who ever played the game. Deion’s most fortuitous moment was when he hooked up with America’s Team just as its owner was doing deals with Pizza Hut, Nike, and Pepsi. No superstar ever had a grander platform.

Thanks largely to the deal with Pepsi and others, Jones was able to circumvent the league’s salary cap and pay Deion a record bonus of nearly $13 million. Signing him was a luxury until the Cowboys’ All-Pro cornerback, Kevin Smith, suffered a torn Achilles tendon in the 1995 season opener; then it became a necessity. The Cowboys could not have won Super Bowl XXX without Deion. They couldn’t have won it without Emmitt Smith, Troy Aikman, or Michael Irvin either, but he was a crucial piece of the puzzle. In an era of high-powered offenses, a cornerback who can cover an opponent’s elite receiver man-for-man is the rarest of talents. Deion can take half the field away from an offense—quarterbacks don’t even try to throw to his side. His contribution to the defense doesn’t show up in his own statistics—nobody keeps track of the number of passes not thrown in his direction—but it shows up in the stats of his teammates. Super Bowl MVP Larry Brown wouldn’t have had the chance to intercept two passes without Deion on the opposite corner.

Deion has what coaches call football speed, a catlike ability to stop, start, change directions, and accelerate in full uniform. He is faster and quicker than most receivers, and his athleticism permits him to overpower stronger opponents. He is also among the craftiest of defenders. He doesn’t taunt receivers; he throws them off stride by asking about their families or offering coaching tips. And he’s a quarterback’s worst nightmare. “He’ll bait you,” says Cowboys backup quarterback Wade Wilson. “He’ll act like he’s beat, you’ll throw the ball, and he’ll somehow make up ground and get it.”

Anytime Deion gets the ball, things happen. As a 49er in 1994, he returned three interceptions for touchdowns. During his NFL career, he has returned two punts and three kickoffs for touchdowns. Though the Cowboys used him only occasionally as a receiver in 1995, he took two of his thirteen regular season receptions into the end zone and averaged 31.7 yards in three playoff catches. Switzer and his coaches saw enough of him as a receiver to restructure this year’s offense; Deion was going to play on the opposite side from Irvin.

Then came Irvin’s five-game suspension following his trial. Now Deion won’t be complementing the All-Pro receiver but replacing him, at least for the first third of the season. It’s a daunting challenge even for an athlete of Deion’s magnitude. While cornerbacks can survive on native ability, receivers must practice endlessly to perfect pass routes and coordinate their timing with the quarterback’s. Irvin didn’t become a standout until his fourth year in the NFL. Hard-pressed by injuries to other key offensive players, the Cowboys cannot allow Deion time to mature on offense. To complicate matters, he will also be expected to play cornerback, at least in key situations. Only one or two players in the modern era have started on both sides of the ball, and no one has played a complete game doing double duty. On average, there are 120 plays in a football game. Deion can’t hold up to that kind of pounding.

Or can he? In the Cowboys’ season opener against the Chicago Bears, Deion played almost the entire game. He played considerably less the next week against the New York Giants because the Cowboys quickly jumped out to a commanding lead, but he caught a touchdown pass and led a defense that limited the Giants to a mere 105 yards. Before the season began, when I expressed my doubts that he could keep up such a pace, Deion’s nostrils flared and his chest began to heave. “All my life people telling me I can’t do something,” he insisted. “I can’t play quarterback [he did in high school]. I’m too small to play college football. And every time, I get the last laugh. I love it when someone tells me I can’t.”

If the Cowboys do make it back to the Super Bowl, Deion will again enjoy the last laugh. The becoming chuckle will slip from the lips of Jekyll, but Hyde’s boisterous guffaw is what we’ll remember.