I first met Stanley Marsh more than thirty years ago, when I was a young newspaper reporter on assignment in Amarillo. He was in his early forties then and one of the most celebrated men in Texas. Reporters from all over the country loved to catalog his quirky eccentricities and mischievous pranks. A natural showman, Marsh had emerged as a supremely savvy and flamboyant (and wealthy) trickster in a time of great tricks. In 1973 he had made President Nixon’s enemies list after he wrote Mrs. Nixon to request that she send him dresses from her wardrobe to fill up the entire first floor of a Museum of Decadent Art he was planning. The following year, in what would become his most celebrated stunt, he paid a group of San Francisco artists to plant ten tail-finned Cadillacs in a field alongside Route 66 outside Amarillo, all of them inclined at the precise angle (52 degrees) of the sides of the Great Pyramid. And just in case anyone hadn’t noticed him yet, in 1975 he attended former governor John Connally’s bribery trial in Washington, D.C., wearing wacky Western clothes—including a pair of purple chaps—and carrying a bucket of cow manure, into which he carefully dipped his boots before entering the courtroom.

A member of a prominent Amarillo oil family that had been in the Panhandle since the 1860’s, Marsh believed that the rich should behave differently than the rest of us. He often came to his office dressed in a loud black-and-white-checkered suit, and he’d sit in a matching black-and-white-checkered upholstered chair, with his pet lion at his side. In the back of Toad Hall, his baronial estate at the edge of town, he built a rustic menagerie and filled it with such creatures as a Clydesdale horse, a zebra named Spot, peacocks, cats, buffalo, Longhorn cattle, ostriches, a two-hump camel, and a hairless Chinese dog with green wings tattooed on his sides—“in case he wants to fly away one day,” Marsh liked to say.

By the time I met him, Marsh was most well-known for the Cadillac Ranch. It had become one of the country’s most popular roadside attractions, a kind of Pop-Art Stonehenge. Magazines held fashion shoots there and bands shot music videos (Bruce Springsteen even sang a song about it). But it was far from his only major project. Marsh commissioned artists to create other impressive public art installations, including Floating Mesa (a section of a flat-topped hill wrapped in metallic screens, which made it appear as if the top of the hill were floating in the air) and World’s Largest Phantom Soft Pool Table (a 180-by-100-foot rectangle of dyed green grass with oversized billiard balls and a 100-foot-long cue stick), both on Marsh’s ranch, about twenty miles north of Toad Hall. He erected a billboard-scale sign on his property that read “Actual Size,” and he created a gargantuan necktie, 40 feet long and 8 feet wide, which he placed around the chimney of his mother’s home. At one point, he decided to become a filmmaker and began shooting a movie (which he never finished) about Lady Godiva, for which he persuaded his pretty wife, Wendy, a prominent rancher’s daughter and graduate of the esteemed Smith College and the University of Texas School of Law, to don a flesh-colored leotard and ride on horseback through the streets of Amarillo.

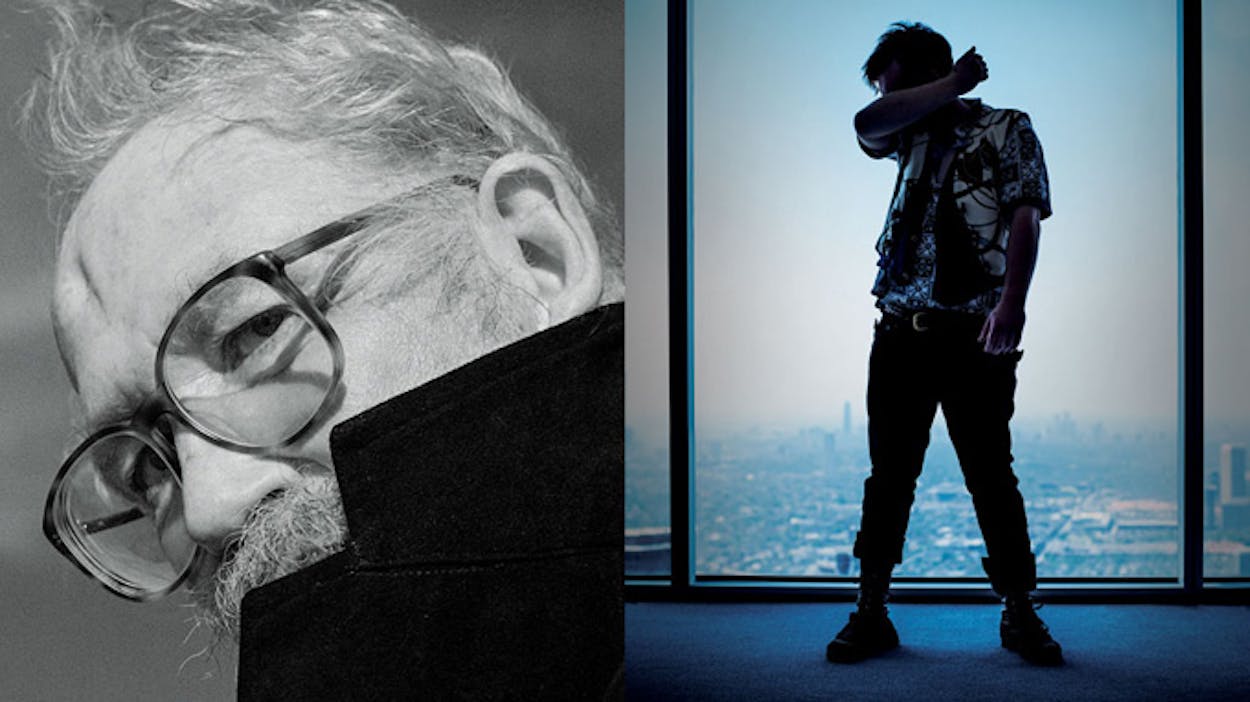

When I had the chance to meet Marsh at his downtown office in 1981, he was dressed in jeans, a billowy barberlike shirt, a red vest, and a bowler hat that didn’t even begin to contain his unruly white hair. The lion wasn’t around, but standing proudly next to Marsh’s desk was Minnesota Fats, a pet pig that had died from eating too much chocolate and had been stuffed and mounted. Marsh stared at me from behind thick glasses that made his eyes look twice as big as normal and said in his exaggerated West Texas twang, “You’re from Dallas? Now, why would you live in a place like Dallas when you could be living it up in rootin’, tootin’ Amarillo?”

I couldn’t have been more charmed. He talked about the philosophers, novelists, and poets he had read, then showed me the window that he periodically opened to drop water balloons on unsuspecting pedestrians. He kept me laughing, explaining how he wanted to collect the boots of dead cowboys west of the Mississippi and build a giant boot hill on his ranch, or describing a party he once threw for a group of Japanese businessmen, to which he invited only men who were at least six feet four in order to reinforce the stereotype of the tall Texan. There were other people waiting to see him, but he seemed to have all the time in the world for me. Finally, as I was heading for the door, he reminded me that although his official name was Stanley Marsh III, he preferred to be called Stanley Marsh 3 because he thought Roman numerals after one’s name were pretentious. I could have turned around, sat back down, and talked to him for the rest of the day.

In 1995, about fifteen years after that first meeting, I briefly saw Marsh again when I returned to Amarillo to write a Texas Monthly story about what appeared to be another comic chapter in his life. Marsh, who was then 57, had put up hundreds of diamond-shaped street signs throughout the town with peculiar slogans like “Ostrich X-ing,” “You Will Never Be the Same,” “Lubbock Is a Grease Spot,” and “Road Does Not End.” Ben Whittenburg, the teenage son of another oil-rich pioneer Panhandle family, had apparently stolen one of the signs, leading Marsh and his employees to hunt him down and lock him in a chicken coop for about fifteen minutes. Incensed, Ben’s father, George, a proper, rock-ribbed conservative Amarillo lawyer, filed a lawsuit against Marsh, claiming that he had brandished a hammer and verbally threatened Ben during the chicken coop incident, which had inflicted “severe emotional distress” on his son. Whittenburg also went to the police to file felony assault charges against Marsh.

During our off-the-record conversation, Marsh was his usual funny self, and I walked away convinced that the elder Whittenburg was nothing more than a Presbyterian church–going windbag. Shortly after that, Whittenburg told me that a sixteen-year-old boy had approached him, alleging that Marsh had sexually assaulted him. Whittenburg claimed he had also met two other boys who said that Marsh had threatened to go on an Amarillo television station he owned and accuse them of stealing unless they went skinny-dipping with him in a pond on his ranch. “Something is going on,” Whittenburg said. “I think he’s recruiting boys for sex.” I tried not to roll my eyes. I figured Whittenburg was so angry over what had happened to his son that he had decided to defame Marsh any way he could. Marsh the merry prankster was actually a sexual predator? Impossible.

Another seventeen years passed. Then, last fall, I heard a piece of news that froze me in my tracks. Tony Buzbee, an enormously successful plaintiff’s attorney in Houston, had filed lawsuits against Marsh on behalf of ten Amarillo teenage boys who were accusing him of sexual abuse. All of them claimed that during the years 2010 and 2011, when they were fifteen, sixteen, and seventeen years old, Marsh had plied them with cash, alcohol, drugs, and even cars as compensation for sexual favors. According to the lawsuits, almost all the encounters had taken place at Marsh’s downtown office, where he had added a bedroom. The boys also alleged that several adults close to Marsh—including his wife, his son Stanley IV, and his business associate David L. Weir, as well as employees of the company that manages his office building and the firm that handles building security—“knew or should have known” about Marsh’s abuse.

“He’s had a stream of boys coming up to his office to do his sexual bidding for a long, long time,” Buzbee told me. “Well, I’m sorry, but that’s going to stop. The real Stanley Marsh is about to be exposed.”

It’s a fitting twist of fate that the lawyer going after Marsh is himself no stranger to ostentation and the grand gesture. In fact, it would be hard to find a more flamboyant Texas attorney than Tony Buzbee. The 44-year-old son of a small-town butcher, he smokes La Gloria Cubana cigars, drives a $500,000 gunmetal-gray McLaren convertible (when he’s not being chauffeured around in his $381,000 Maybach 57 S), and spends weekends at his ranch or in the Cayman Islands or on a yacht he keeps in Florida. He owns three private jets, one of which, a Challenger 600, he has nicknamed the Shark. He also prefers to wear shark cufflinks to work. His law firm takes up most of the seventy-third floor of Houston’s JPMorgan Chase Tower, the state’s tallest building.

Buzbee has made his reputation going after corporations, and he usually wins big. In 2005 he won a $16.6 million verdict against Ford Motor Company on behalf of the family of a thirteen-year-old boy who was killed in a Ford Explorer rollover accident, and in one of his most recent cases, in which he sued BP on behalf of nineteen workers injured in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon rig explosion and oil spill, he won a settlement exceeding $150 million. “I was born with a chip on my shoulder, and it’s still there,” he told me. “I live for fighting on behalf of the weak against the powerful. I enjoy getting my clients a bunch of money and putting the fear of God in those who are unfortunate enough to oppose me.”

Last October, Buzbee got a call from an Amarillo attorney he barely knew. The attorney asked Buzbee if he’d take on the case of a teenage boy who claimed he had been sexually abused by Stanley Marsh. “I’m not the right guy to do it,” said the attorney (who asked that his name not be used). “Stanley’s got too much power for me to fight him. He’s an institution in Amarillo.”

Buzbee was dubious. Civil cases regarding sexual assault are hard to prove and don’t necessarily result in the kind of big-money verdicts Buzbee likes. But the idea of knocking down a powerful person appealed to him. And he became especially interested when the Amarillo attorney told him the teenager’s mother had gone to the police that summer to file charges against Marsh. “But they haven’t done a thing,” the attorney said.

Buzbee sent the Shark to Amarillo to pick up the teenager and his mother and bring them to Houston for an interview. What the teenager said “just about knocked me out of my chair,” Buzbee told me. I got a chance to hear the teenager’s story for myself earlier this year, when I met him and his mother at Buzbee’s office. Now seventeen, he was dressed in the kind of outfit Marsh himself might wear: a green fedora, a white T-shirt with a denim vest, and low-slung khakis worn over jeans rolled to the top of a pair of ropers that had been spray-painted half a dozen colors. He had red hair that was short on the sides and thick on the top, and his skin was so smooth it looked as if he didn’t need to shave.

“In Amarillo, I never fit in,” he told me. “I wrote avant-garde poetry. I wanted to be an artist. Everybody told me I was a freak, weird, and a f— up. And maybe I was. Then I got to meet Stanley. For a kid like me, Stanley Marsh was my icon, my hero, the father figure I never had. All I wanted to do was work for Stanley.”

So far, nothing he had said surprised me. For decades, Marsh had hired teenage boys and young men to help him around his ranch and his estate or with his art projects. Back in the seventies, they were known as “hippie hands” or “Stanley kids.” They tended to be from blue-collar families, kids who weren’t part of the popular crowd at their high schools. Some of them had gotten into scrapes with the law or had problems with alcohol or drugs. A few were self-described punks. Marsh had turned his office on the twelfth floor of Amarillo’s Chase Tower into a kind of clubhouse for them, letting them ride their skateboards down the hallway and make their own art in the conference rooms.

The teenager told me that the first time he met Marsh was the day before he turned fifteen. “There were other kids like me up there working in a big open room they called the Croquet Room,” he said. “I got invited back to Stanley’s office, and there he was, sitting on a couch. We talked about art and movies. When I told him I loved The Bridge on the River Kwai, he told me that it was his favorite movie too. I felt like I was hanging around someone really famous, like Andy Warhol. He told me I was artsy and talented, and he said he could tell I was going to be prosperous from the second he met me.”

The teenager stared at the floor for at least fifteen seconds. “Then he invited me to come back to see him the next day, and that’s when it all started. He asked me if I had ever masturbated in front of someone. He said that’s what all the intellectuals and great artists did and that if I did it, I would be smarter. He made it seem like it was the right thing to do. So I did. He had porn playing on his television. I was so disgusted I didn’t know what to do with myself. But he gave me five hundred dollars and asked me to come back again soon because now I was part of his group.”

There was another silence. “And I did come back,” the teenager said. “I came back because I wanted to be part of his group. I wanted his approval.”

On the third visit, the teenager recalled, he took a Viagra that Marsh gave him—“he had Viagra pills all over his office”—and he let Marsh masturbate him. Once again, he said, Marsh paid him $500. On subsequent visits, according to the teenager, Marsh engaged in all manner of sex acts with him. He watched him take a shower and then performed fellatio on him. Despite rarely being able to get an erection, Marsh attempted to have the teenager perform fellatio on him. He tried to have anal intercourse with the teenager. He asked the boy if he could pour oil on his body and lick it off (which he called a “sex salad”).

As time passed, the teenager said, Marsh began to pay him thousands of dollars for these sex acts. Before he even turned sixteen, Marsh bought him a BMW. When he wrecked it, Marsh bought him a second one (he wrecked that one too, right before he turned seventeen). He also gave the teenager a bonus of $1,000 whenever he brought in another boy who was willing to engage in sex acts with Marsh. During one incident, the teenager explained, Marsh sat between him and another boy on the couch and masturbated them simultaneously.

“And every time you went to his office, you passed by his employees?” I asked.

“His secretary, his bookkeeper, his lawyer, his own son,” he said. “They had to know what I was doing behind that locked door. They had to know what all the guys were doing who came up to see him—at least twenty that I can think of. And they never said a word.”

The teenager swallowed, clearly trying not to cry. “Yeah, the money helped me do what he wanted,” he said. “And he told me he would pay for boarding school and for college.” He paused. “But he never asked if I was okay with this. He didn’t give a shit. When he saw that I felt ashamed or didn’t want to do it, he would say, ‘I’m sorry, are you not my real friend?’ He would put me down and make me feel like I was nothing. He’d say, ‘You’re not a real artist, because every artist is bisexual.’ ”

Over time, the teenager told me, he began drinking “to knock off the pain.” When that didn’t work, he began using heroin so that he’d be “high out of my mind” when he had his liaisons with Marsh. “But none of it was ever enough. I was drinking so many bottles of McCormick and doing so many drugs that I was out of control. I’d see my mom crying at night. She kept asking what was going on with me, but I didn’t know how I could tell her.”

I asked the teenager’s mother if she ever questioned her son about why Marsh was giving him so much cash and two nice cars. “Oh, I was very suspicious. But I was always told by everyone I asked that this was simply what Stanley did: provide financial support and college scholarships to Amarillo boys he thought were talented. One day Stanley himself showed up at my house—he was driving this car with a stuffed dead animal on top of it—and he said, ‘I’m Stanley Marsh and I’m highly admiring of your son, and I think it’s important he’s part of my mentoring program so he can get his life together.’ I just remember I couldn’t talk. I didn’t know what to say. Afterward, I guess I explained it all away to myself by saying that surely if someone that prominent in the community was doing something wrong, someone would have stopped him by now. He would have been prosecuted.”

It wasn’t until July 2012, when the teenager was placed in a drug rehabilitation center, that he told an adult about the sexual encounters with Marsh. He confessed to a counselor, who called his mother, who persuaded her son to go with her to the police. “What Stanley Marsh did to my son is too horrible,” the mother told me. “He destroyed his young life. And now all we want is justice, all the way around.”

After his initial meeting with the teenager and his mother, Buzbee sent the Shark to pick up a close friend of the teenager’s who also said that he had been involved in sexual encounters with Marsh. He told Buzbee that starting in 2010, when he was sixteen, he had been paid by Marsh to engage in sexual acts with him as many as twenty times. He said that he too had been plied with Viagra to maintain erections and had ended up drinking heavy amounts of alcohol at Marsh’s office (usually Grey Goose vodka) and buying drugs off the street (Xanax and cocaine) to deal with the shame. “Sometimes I’d sit in my room or drive around and think, ‘I did it. I’m going to hell,’ ” the second teenager said when I met him. Suddenly he choked up. “But that man told me all the right things I wanted to hear. He got into my head. What he made me do was bullshit. It’s bullshit. And now I’m the one who has to live with it.”

Buzbee quickly filed two lawsuits on behalf of the teenage boys—whom he named John Doe #1 and John Doe #2—and then, in his typical aggressive style, he took out full-page advertisements in the Amarillo Globe-News that read, “Our firm represents multiple young men who were allegedly sexually assaulted by Stanley Marsh 3. If you have information about these allegations, or any similar conduct by Mr. Marsh no matter when it occurred, we want to speak to you immediately.”

Within days, Buzbee had met with eight other Amarillo teenagers who he decided had strong cases against Marsh. He said he also talked to “easily a dozen other young males” who claimed they had been sexually abused by Marsh, but he was unable to take them on as clients because the statute of limitations for them had passed (according to state law, a minor who claims to have been sexually assaulted by an adult must file a civil suit within two years after his or her eighteenth birthday). “I even talked to a father who said his thirty-three-year-old son had recently died and could never get over what Marsh had done to him back when he was a teenager.”

Most of the stories Buzbee was turning up were at least a few years old. He couldn’t find anyone who claimed to have been sexually abused by Marsh after November 2011; Buzbee attributed this to a series of strokes Marsh had suffered at that time (it’s still not clear how serious those strokes were; Marsh has been staying mostly at his home since then). But his target’s frailty did nothing to deter Buzbee. “I had no sympathy for that old man whatsoever,” he said. “I had no doubt that unless we filed the lawsuits, he would start up his assaults again as soon as he began to get better.”

After Buzbee started filing lawsuits, the Amarillo police received a court-ordered warrant to search Marsh’s office. Officers took away seventy envelopes of “blue pills,” along with couch cushions, a comforter, and pillowcases that supposedly contained DNA evidence, and they found a stack of identical unsigned legal documents that released Marsh, his employees, and his companies “from any and all liability” regarding any claims “of any nature.” Buzbee was convinced that Marsh or one of his staffers had the teenagers who came to the office sign one of those documents, devised solely to scare them off from going to the authorities.

Marsh was arrested in late November on charges of sexual assault and sexual performance by a child, second-degree felonies punishable by two to twenty years in prison. When he was pushed through the front doors of the sheriff’s department in a wheelchair after posting bond, photographers were there to take his picture, which circulated around the country. His hair askew, he looked feeble and confused.

Marsh’s attorneys, Paul Nugent and Heather Peterson, of Houston, said in a statement: “The criminal charges against Stanley Marsh 3 are mere allegations by the group of accusers who have filed a barrage of civil lawsuits against Marsh seeking millions of dollars. . . . After Stanley Marsh 3 suffered a massive stroke and became legally incapacitated, the group implemented their plan to become multimillionaires by signing contracts with an aggressive personal injury lawyer from Houston. . . . Stanley Marsh 3 is not guilty of the group’s allegations.” (Marsh and his attorneys refused to comment for this story.)

Not surprisingly, the story dominated local media coverage for weeks, and the website of the Amarillo Globe-News became a kind of town square where Amarilloans reckoned with the possibility that they had allowed this to transpire for decades right under their noses. A handful of locals posted comments lambasting Buzbee (“a class action hack out of Houston”) and the teenagers (“vultures . . . just out for money”), but it was clear that the majority wanted Marsh to pay. “I hope Marsh goes down in flames before he kicks the bucket,” wrote one. “My only hope is that he spends his final years in the tank,” said another. Several people were so angry they demanded that the Cadillac Ranch be bulldozed and Marsh’s street signs torn down. “It’s time to purge this city of his filth!” someone wrote. And then there was this: “Perhaps a sign should be erected at the Cadillac Ranch that says, ‘A Perv and his caddys, finally parted.’ ”

After Marsh’s arrest, I called Whittenburg. “Was I simply blind to what was going on all those years ago?” I asked him.

“I think a lot of people in Amarillo were blind,” Whittenburg replied with a sigh. “Or they didn’t want to see what was going on. Stanley’s always been viewed as so powerful and so erratic that people didn’t want to confront him. I would have parents of boys tell me that. And it’s true that lawyers who work in this community didn’t want to go against him. They knew he had a lot of strings to pull to get back at them.”

In fact, Marsh was never publicly accused of having sex with a minor until Whittenburg went after him, in 1995. After meeting the sixteen-year-old boy who claimed Marsh had sexually assaulted him, Whittenburg called the police to report the incident. Officers talked to the teenager, which led to Marsh’s being indicted on three felony counts of indecency with a minor. A Fort Worth attorney representing the boy also sent Marsh a demand letter claiming that a lawsuit was pending. But before it could be filed, Marsh’s attorney arranged for the teenager to receive a sum of money, with Marsh admitting no wrongdoing. The criminal case was also dismissed at the request of the teenager and his father.

In the aftermath of that case, Whittenburg said, he was approached by “seven or eight” other young males who wanted to sue Marsh for alleged sexual abuse. Whittenburg agreed to represent three of them. In 2001, however, before any evidence was submitted in court, Marsh’s attorneys made a confidential settlement with the three teenagers. What’s more, they settled the lawsuit Whittenburg had filed on behalf of his son, relating to the chicken coop incident (the terms were also confidential, but Marsh did make a public apology to the younger Whittenburg), and also arranged for Marsh to plead no contest to a misdemeanor charge of unlawful restraint. He paid a $4,000 fine and did some community service. “As far as I was concerned, Stanley got off easy,” said Whittenburg.

So in 2004 Whittenburg tried again. He filed another lawsuit against Marsh on behalf of an eighteen-year-old male who claimed he had been sexually assaulted after going to have lunch with Marsh. The allegations were denied by Marsh, and, predictably, the suit was later dismissed after his attorneys made another out-of-court settlement with the plaintiff.

“Stanley’s strategy was to make quick settlements and say nothing,” said Whittenburg. “And it worked. A lot of people tended to believe that these young men were just trying to take advantage of Stanley and get at his money and that he was better off settling than letting them drag him and his family through the mud.”

“Or, like me, they thought you had a vendetta against him,” I said.

Whittenburg sighed again. “Trust me,” he said, “the last thing I wanted to do was take on Amarillo’s favorite son.”

Still, it was hard to believe that no one, aside from Whittenburg, had realized what was really going on. I asked Amarillo’s state senator, Kel Seliger, who was mayor of the city from 1993 to 2000, what his constituents thought about Marsh during those years. He acknowledged that there were rumors circulating regarding Marsh’s relationships with young males. But as for the lawsuits, he said, “there was this feeling around town that these were random and perhaps exaggerated accusations being made against a wealthy and notable person and that they should be taken with a grain of salt. They were allegations, nothing more.” There was another issue too. John Smithee, a longtime Amarillo lawyer and a state representative since 1985, explained to me that a lot of people simply didn’t trust the young males who were making the allegations. “It was difficult for people to believe those kids’ stories about someone who had brought such wonderful attention to Amarillo,” he told me.

And that’s where the situation seemed to stand—until Tony Buzbee arrived with the new lawsuits. Soon after, Marsh was arrested. “I have to admit, that changed things,” said Seliger. “That changed things a lot.”

But had things really changed? In February lawyers for Marsh, his wife, his son, and his business associate settled with Buzbee’s ten plaintiffs without acknowledging any wrongdoing. The settlement is confidential, and the parties involved have agreed not to discuss any aspect of the lawsuits. But the story around Amarillo is that the city now has ten new multimillionaires, all of them eighteen years old or under. And Marsh’s downtown office is closed for good. Marsh himself remains in seclusion at Toad Hall.

During my conversations with Buzbee, he said that if he made a settlement with Marsh, he was going to demand that the Cadillac Ranch be knocked down. “When people find out what this man is really like, they’ll want to come out and help me bulldoze the place,” he told me. “We do not need a monument that honors an alleged child predator.” Apparently, he didn’t win that battle. In a statement released by attorneys from both sides announcing the settlement, there was a curious sentence that read, “The parties agree that Stanley Marsh 3 does not own the Cadillac Ranch.” (It’s on land that belongs to Marsh’s wife’s family.)

Nevertheless, it’s going to be next to impossible for anyone to look at the Cadillac Ranch the same way again, especially if Marsh is sent off to prison after criminal proceedings against him are concluded, which will probably be later this year. It’s conceivable that his attorneys will tell the judge that Marsh, because of his strokes, is mentally unable to assist in his own defense and is incompetent to stand trial. Or they may try to cut a deal to put Marsh on a lengthy probation that would last until he dies. Whatever happens, the Puck of the Panhandle is no more.

Meanwhile, Buzbee’s ten plaintiffs are moving on with their lives—some of them literally, moving to cities where they are not known. “Other kids in Amarillo know who we are,” said the teenager who first spoke to Buzbee. “They call us ‘Stanley’s fags,’ and they say we don’t deserve anything because we let Stanley do all those things to us.”

Once again, the teenager stared at the floor, and after several seconds, he looked at his mother. “I think my mom has forgiven me. Now it’s time for me to forgive myself. I’m not sure I can ever do that.” And then he started to weep.