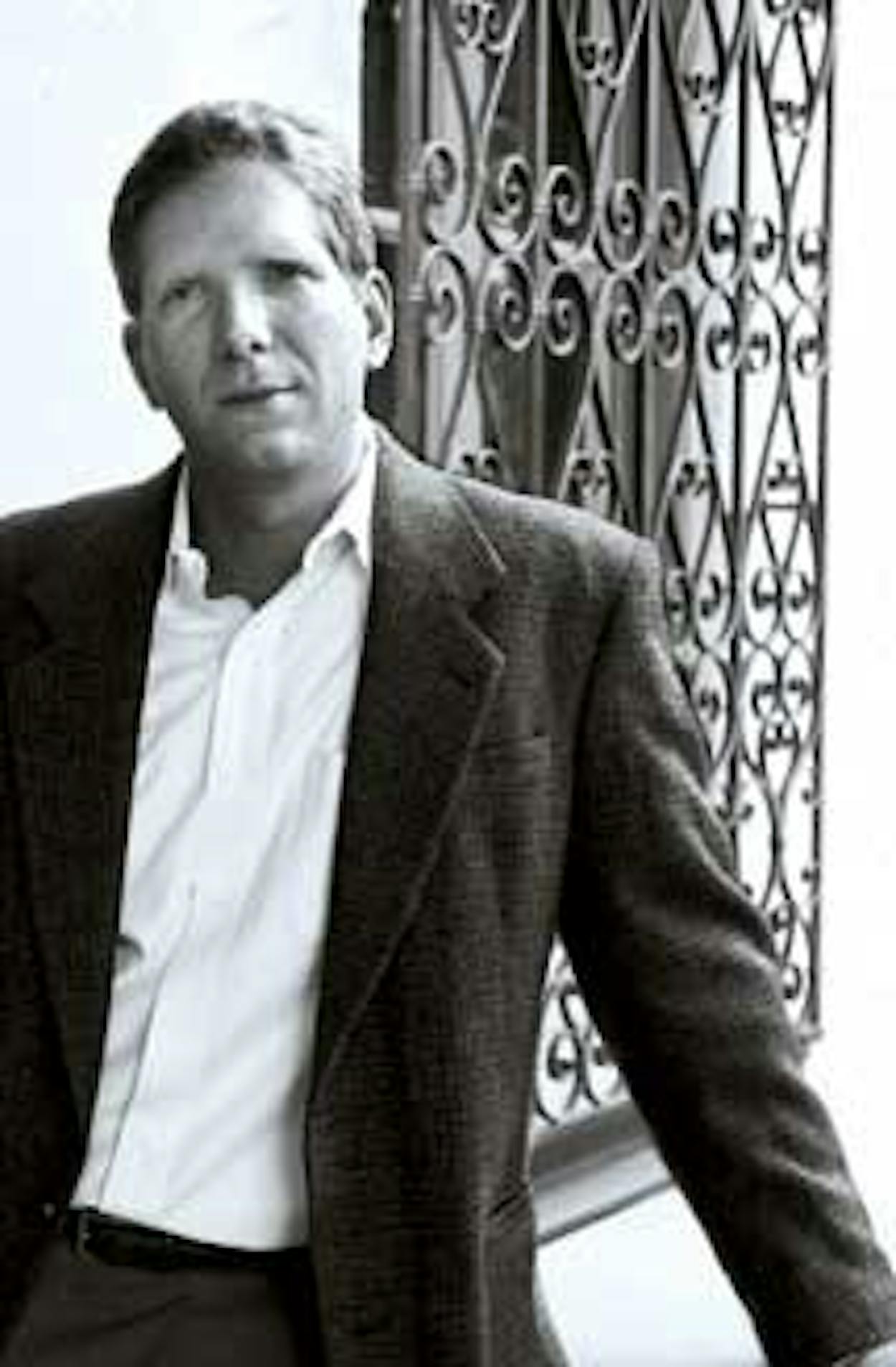

The San Antonio author has exhibited an impressive sense of worldliness with his literary mysteries, the settings of which range from seventeenth-century Amsterdam to twentieth-century Florida. The Devil’s Company, his sixth novel, returns to eighteenth-century London, where pugilist-turned-PI Benjamin Weaver—who first appeared in A Conspiracy of Paper and later in A Spectacle of Corruption—becomes embroiled in the intrigues of the British East India Company. Liss has regularly appeared on the New York Times Notable Books list and was the 2001 winner of the Barry, Macavity, and Edgar awards for best first novel.

Compare your current perspective on writing with your attitude after your first book, A Conspiracy of Paper. When I started out, it was a much more desperate kind of writing. With my first book, I wanted to produce something that I could publish. With my second novel, I was terrified I would not be able to do it again. Now I write with the knowledge that—barring any major disasters in publishing, and these days nothing can be ruled out—I am going to get it published, and that is very liberating.

Why are you drawn to the past for your settings? When I set out to write my first novel, I was in grad school studying eighteenth-century British lit, and I went with the adage “Write what you know.” There is a genuine pleasure in excavating and working with historical cultures and subjectivities. In some ways, writing about the past allows me to make fairly broad arguments about the present.

What was it like bringing back Benjamin Weaver? There is something very comfortable in returning to a familiar character and narrative. On the other hand, I think doing only that would get very dull very quickly. This new novel, for example, does not work with a mystery format. It is more of an espionage thriller. I get rid of some of the secondary characters from the previous books and introduce some new ones that will stick around should I decide to return to this universe again.

You tend to mine the world marketplace for plots, as with The Coffee Trader and The Whiskey Rebels. Does international finance play a role in the new book? I am interested in financial history, and that shows in The Devil’s Company, which is very much concerned with the eighteenth-century forerunners of modern corporations. There are a number of interesting points of contact between the economic conditions in the background of the novel and our own economic climate today.

By informing your readers about the past, do you perhaps sway their actions in the here and now? Trying to make a significant difference with a single novel, or even a whole body of work, is a losing strategy. I want to be one part of a provocative discourse that will, in some way, stand on the side of the scale that represents a broader cultural awareness. I’d rather be one of the grains of sand that could tip the scale toward social responsibility than to be off the scale entirely.

Your brand of history and mystery would make good film fodder. Have you fielded much interest on that front? There are projects under various stages of development for The Coffee Trader, A Conspiracy of Paper, and a short story I wrote called “Minesweeper.” I’ve had enough dealings with the film industry that I’m fairly cynical at this point.

Who would be your ideal Benjamin Weaver on-screen? When the Conspiracy project was hot the first time around, I thought the guy perfect for the job was an up-and-coming actor with whom most people were not familiar named Russell Crowe. Today I would be inclined toward Clive Owen or maybe Daniel Craig—clearly the best gentile to play a bad-ass Jew.

Read an excerpt of The Devil’s Company. Random House, $25