The characters and events in this story—including the narrator—are based upon a number of people and circumstances in different parts of the state. None are real; all are real.

A crescent wrench has been pressed into service as a roach clip. It will do, of course, but one misses the sacramental paraphernalia, the turquoise-inlaid alligator clamps that double as key chains, the sterling silver tweezers that were meant to be passed down as heirlooms from father to son, all the gilded trappings and geegaws that in earlier days elevated the use of marijuana from routine to ritual.

Not that I’m all that sentimental about Cannabis sativa. In fact, when the joint comes my way I compose a gesture made flawless by nearly a decade of repetition: a palm-outward, upwardly diagonal wave of the hand accompanied by an indecipherable chortle that has a certain negative musicality to it. Not so long ago, this gesture—the unmistakable mark of the nark—would have spelled the end of the story you are about to read. But today the joint travels past me with barely a hitch and is taken up by Wesley, who, seeing that its powers are depleted, casually eats it.

Maybe I am a little sentimental. I remember when ingesting a roach like that was an act of derring-do, performed on special occasions by the kind of people who open beer bottles with their teeth. But that decadence is now an off-hand mannerism, the evil weed itself is pending canonization as a miracle drug, and the dealers who were shooting it out with the federales in the mountains of Guerrero while their clients were writing term papers explicating the lyrics of Ultimate Spinach are not so simply the counterculture Good Humor men we once took them to be. Within their isolated world, free enterprise has been growing like an experimental culture, and they have now found themselves to be businessmen, with tax lawyers and airplanes and the kind of money it takes expertise and imagination to spend.

Scott looks down at the shoe box lid on which he has been cleaning dope and discovers that he has nothing left but seeds. For a moment he appears inexplicably bemused, as though the seeds, like tea leaves, have just revealed some cryptic message. But he recovers immediately and walks across the living room to the closet, from which he extracts a small plastic garbage bag filled with bundled Oaxacan grass. When he is seated again and has the bag open on his lap, I notice a small orange object inside.

“That’s a carrot,” he says with inordinate pride, holding it up to the overhead light. “A trick of the trade. It absorbs moisture and keeps the pot fresh. I’ve been meaning to write ‘Dear Heloise’ about it.”

“You ever seen those Yankees with those goddamn steamers they use to fluff their bricks back up?” Wesley asks Scott.

“Listen, I’ve seen whole stash rooms with all four walls covered with mildew. Yankees, man, they’ll try anything.”

Wesley leans back on the sofa and laughs to himself, a deep, rumbling laugh that does not seem to suit him. He’s very tall and lithe, and bent nearly into a W, with the heels of his boots hooked under the redwood coffee table and the dark, wiry top of his head pressed against the paneled wall, throwing his eyes upward to the ceiling.

Soon Scott has another lopsided joint rolled. He strikes a kitchen match on the zipper of his Levi’s and the air is infested with the smell of sulfur and the harsh, sweet bouquet of marijuana.

The joint comes my way again. I wave it on once more, knowing from experience that it will take five or six passes for the fact of my abstinence to break the conditioned reflex, born out of communal etiquette, that requires the pipe of peace to be passed to your neighbor. I have no very impressive reasons for refusing: a few childhood evenings spent with a rasping humidifier could help to explain my intolerance for fumes of any sort, but I don’t know what regulatory mechanism is responsible for a more or less persistent notion that getting high is, as Jack Webb himself might put it, “just plain silly.”

This will be seen as an admirable attitude in some circles, but in the environment in which I existed as a grave and pure-hearted college student in the late Sixties, it was, at best, an anomaly. I did my best to fit in, chose a few pills at random from the great drug smorgasbord, but I was still estranged where it counted most. Scores of times every day joints wrapped in sickly yellow paper would waft before my sober countenance with metronomic regularity, accompanied by the shrill nerveless music I wanted simultaneously to shut out and learn to love.

The few dealers I knew then I thought of as hobbyists, as hip equivalents of housewives who sell Tupperware. It never occurred to me that dealing could be a serious occupation, but marijuana then was a growth industry, a brand-new corporate blob, quivering and formless, the way petroleum must have been before John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil. People I knew began dealing a few lids, then a few pounds, then sometimes signing on as “mules” for larger operations and getting busted on the wrong side of the border. Still, there were and are few “former dealers.” The felons came back to the fold. If marijuana itself has been proven to be nonaddictive, the same cannot be said for its procurement and dispersal. The money, the risks, the allure of dope trafficking created its own junkies.

The risks are still around, but here in Scott’s house they are seen more as business nuisances, threats less to hearth and home than to accounts receivable. Though there are four or five hundred pounds of marijuana in the garage and an ounce or so of cocaine secreted about the room there is no evidence of any paranoia. Scott’s three children are watching Adventures of Rin Tin Tin, his wife, Arnette, a former small-town beauty queen, is fixing me a Dr Pepper, and he and Wesley are warmly reminiscing, for my benefit, about the old days. There is nothing like a dealer’s nostalgia: those golden near-misses etched in adrenaline.

“Back then we didn’t have a plane or a van or any of this shit we’ve got now,” Wesley is saying. “We had backpacks. We’d fill those up with weed and walk it across the river. On the Mexican side you had to walk through about a hundred yards of cane. That’s hairy, man, trying to keep quiet walking through all that cane.”

He takes a deep toke and continues, speaking from his lungs.

“One time—there was a full moon—we were waiting by the river, putting on our tennis shoes and getting ready to cross, when we hear somebody behind us. Turns out to be about ten or twelve guys in wet suits, carrying machine guns and heading for the river same as us. They must have been heroin smugglers. Anyway, I just took out my pistol and pointed it at the head guy and tracked him all the way. They never saw us, but my heart was in my throat and my balls was somewhere near my armpits by the time they got past. It was a good feeling, though, you know? Invigorating as hell. It’s a real high.”

But those kind of highs are, for the most part, behind them now. Scott takes out a brochure and shows me pictures of the “executive model” twin-engine four-passenger Aerocommander he and Wesley have just bought for $200,000.

Yes, they have reached the big time. With this airplane, with luck, with a good crop in Oaxaca, Scott and Wesley figure they can each make about $600,000 this year. Tax free.

My eyes wander about the house for some evidence of that wealth, but there is little for them to settle on. There are a few antiques, three color TVs, one luxury automobile and a fleet of trucks and campers, a pool table, a draft beer tap on the refrigerator, and a pamphlet describing a luxury dog kennel. But all this is subtly woven into a working-class decor. Rotting machine hulks graze on the same grounds with four-wheel-drive dream vehicles. On the living room wall four wooden ducks fly upward into the open mouth of a large stuffed mackerel. The lawn needs cutting, the wheels of the kids’ plastic tricycles are split, the Roto-Rooter man is digging up the yard.

Scott cannot yet afford the luxury of leaving his wealth free to seek its own level. Opulence is too visible. Though he seems to enjoy tinkering with the components of his low-profile life, it is plain that he wants someday to be recognized for his accomplishments. He is, after all, a young man who has accrued considerable riches through an enterprise that is, if outside the law, thoroughly within the system.

Dealing, all in all, is a paradigm of the ideal American way of doing business.

Granted it is a primitive and pristine version of the system: business is conducted with power handshakes and ceremonial reefers rather than with contracts; important connections are established or dropped with as much, if not more, instinct and savvy than in the straight world; workers are paid beneficently and in cash and have ample opportunities for advancement; and the product is always in demand and requires no cynical advertising ploys to create consumers. Dealing, all in all, is a paradigm of the ideal American way of doing business.

But it also shares certain worldly concerns with traditional commerce. Scott will pay about $1200 in taxes this year, based on the reportable income he receives as co-owner of an apartment complex he and Wesley bought some months ago. That his tax rate is vastly disproportionate to his gross income is hardly out of keeping with standard corporate procedure. Some of the money saved from the clutches of the IRS finds its way into community-minded projects. Scott and Wesley are thinking of opening a continental restaurant in a once-dilapidated section of the city that has been significantly restored, largely by other dealers. They don’t expect to make much money at first on such a venture, but they feel they owe a few debts to the culture which has supported them. It’s just good public relations.

Arnette brings my Dr Pepper and sits down in time to intercept the reefer as it continues its sweep of our circle. She’s wearing an old T-shirt, the one with the R. Crumb characters “truckin’’ across the front. She’s about 30—four or five years older than Scott—and it is easy to detect the beauty queen in her, though that small-town prettiness has long since graven itself into something more profound. Scott remembers the first time he saw her: he was a boy scout, thirteen years old, marching down Main Street behind the float that bore her throne, upon which she sat blowing kisses and waving, profoundly unapproachable.

“If somebody had told me back then when I was working on my citizenship merit badge that someday I’d marry that girl on the float and be making over a half-million a year selling marijuana, I would have thought they had their poles reversed. God, life is strange.”

Scott finishes this reverie and Arnette, taking advantage of the kids’ absorption with the TV, picks up a biography of Virginia Woolf. The weight of nostalgia shifts back to dealing, and as the afternoon wears on, Scott and Wesley’s climb up the rungs of one of the nation’s great invisible corporate ladders is revealed.

In 1970 Scott was driving a mail truck after two unsuccessful years at college, living off and on with Arnette, and scoring an occasional lid or two for his own personal use from his friend Wesley, who had lately been involved in some marginally nefarious doings, such as driving down to Mexico with loads of contraband air conditioners, TVs, disposable diapers, and cases of Nestle Quik. It wasn’t long before Wesley decided to realize some profit on his return trip and entered the fast-growing field of marijuana smuggling. He crossed the river, sometimes on foot, but more often with a van-load, taking pains to keep his hair short, his cowboy hat on, his West Texas accent and demeanor at full throttle when he approached the border guard disguised as a lonely shit-kicker whose heart was just broke in Boys Town.

It worked often enough for Wesley to put together a scam involving 200 kilos of grass, which he paid a farmer for in Oaxaca and left his partner sitting on while he went back to the States to rent a van. He returned to find that his partner had panicked, moved to Guadalajara with the load and generally behaved in a very uncool fashion. The slightest pressure induced him to finger Wesley, who subsequently spent fifteen months in a Guadalajara jail dodging cattle prods.

A week after he was released from prison Wesley sought out Scott. His incarceration had provided him with a little black notebook filled with important contacts. Scott was married by this time, Arnette was pregnant, and he had $200 he could use either to pay the rent or to provide operating capital for a promising—although illegal—business venture. There was no contest.

They played it shrewd, transporting the grass in an ingenious manner that is still being used successfully today. They would sell the marijuana from neutral ground in large quantities to a small number of trusted buyers. The loads got larger, so they began renting planes and hiring freelance pilots to fly them. They would meet the flights at midday on abandoned highways.

And so they got rich, and explored various ways of spending their money: they bought motorcycles, they bought Charlie Dunn boots with cannabis leaves tooled into the leather and big white lone stars on each toe, they got strung out on cocaine and put gold coke spoons on their key chains next to the roach clips, they bought leather pants, guard dogs, guns, paid astrologers to cast their charts, subsidized spaced-out filmmakers and became patrons of poets who wrote dazed, rhyming-couplet epics about the outlaw life.

It wasn’t long, though, before Scott and Wesley began to suffer growing pains. They sensed that they had overstayed their welcome in adolescence, so they put aside the things of outlawhood and became adults and businessmen. They bought the apartment complex, and the IRS was soon notified that they managed these apartments for their business. The IRS did not know, of course, that Scott and Wesley had found a Realtor more than happy to accept a $10,000 bribe in return for officially noting that their down payment on the complex had been only $5000. Thus they had a tax shelter, a Laundromat for their money, and a profitable side venture—all at the same time.

Scott already has a lot paid for, more or less on the sly, in a fashionable neighborhood of the city. As his reportable income unobtrusively rises, so will his standard of living. But for now, while he dreams of building a stone and glass house on that lot, his life must appear a little drab and dog-eared with a minimum of nouveau-riche distractions.

During the afternoon four or five different groups of dealers arrive, subcontractors who are buying parts of the load in Scott’s garage. The dealers all seem to have clean chin-lines and dark, narrow eyes. They scratch their crotches, wear hunting knives on their belts and John Deere caps on their heads, and are discreetly spangled with turquoise and silver.

Before any money is turned over, they share a joint with Scott and Wesley and complain about their women. “My old lady decides to give a goddamn tea party and it costs me three grams of cocaine,” one of them says.

Between visits Scott takes me out to see his stash. The garage in which it is kept contains a large amount of hay whose organic aroma cannot hide the ripe, hot-house smell of a large amount of marijuana. The weed shares the underside of an orange tarpaulin with an advanced model of the humidifier I once found so distasteful. This is all loose, rather elitist grass, from the top of the cannabis plant. Scott also deals with “commercial” weed, in which the whole plant is indiscriminately pressed into a brick and sent out to the masses. On one side of the garage is an intricate set of scales about three feet long, no doubt special-ordered at great expense from a laboratory supply house. (I remember an acquaintance proudly displaying a letter scale he’d ripped off from the post office.)

“Isn’t it kind of dangerous to deal out of your house like this?” I ask.

“Sure, a little. But it’s only temporary. Usually we’ll pay somebody a few grand to let us use their house for a while. But it’s really not that much of a risk, anyway, not with the kind of solid contacts we’ve built up. Besides, I believe in such a thing as being overcautious and showing your hand that way. I don’t like dealing with paranoid people—it makes me paranoid.”

One day I drive out to a little town just barely within commuting distance of the city to talk with Ferguson, a freelance operative who has done some work for Scott and Wesley as a driver. The directions Ferguson has given me over the phone are flawless and I have little trouble locating his house. Approaching it, though, is a different matter. At a high mesh gate guarding a long, tree-lined driveway I find myself looking down at four frothing sets of German shepherd teeth.

The dogs lapse into meekness the moment Ferguson comes out of the house to meet me.

“These dogs are the best insurance a dealer can have,” he tells me as he opens the gate. “That one there’s been busted in Texas and Arkansas and Lousy-ana and she ain’t gonna let nobody in a suit near her.

“They’re also good insurance against your regular rip-off artists. Dealers are perfect targets for them ’cause we can’t report any of that kind of shit to the pigs. A friend of ours down the road just had his juicer and all his guns lifted.”

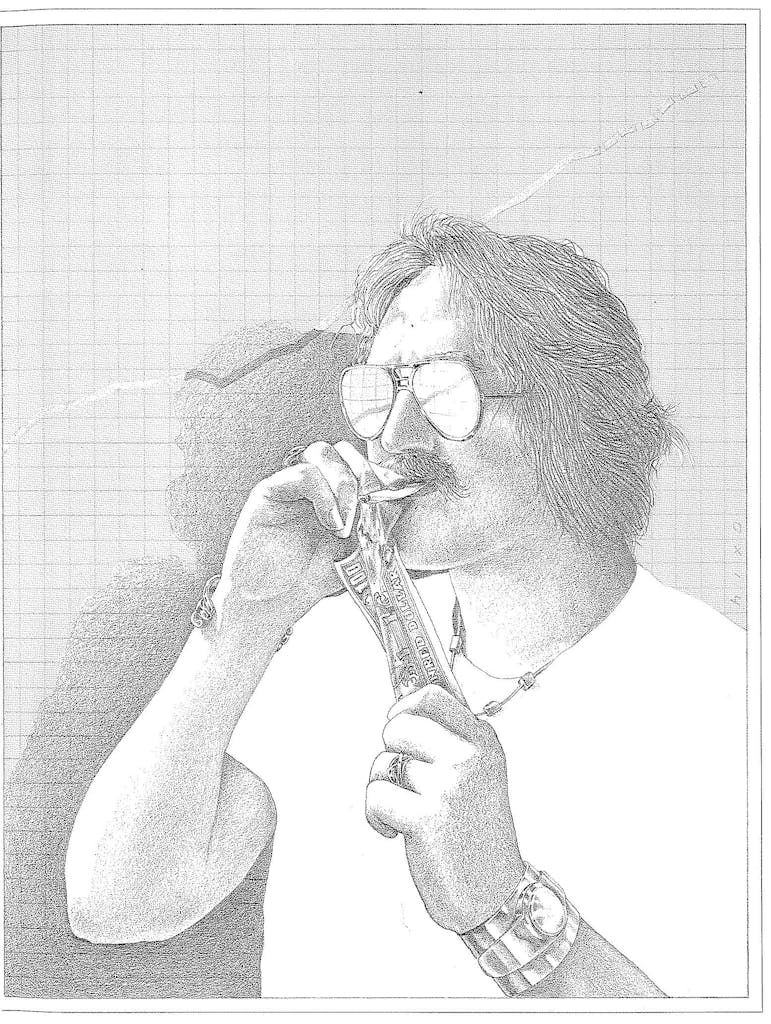

Ferguson has so many outsized features it’s hard to gauge his size and appearance at all. The greater part of his face has been reclaimed by a huge beard whose tip, in certain dilapidated postures, almost touches the summit of his Heineken-maintained beer gut. He has his long hair tied up into a samurai topknot.

“You know anything about table saws?” he asks. “I just bought this son of a bitch and now it won’t cut straight.”

Ferguson’s backyard is littered with camper shells and sheets of plywood that have been half-sawed and ruined by the new machine. One of Ferguson’s sidelines is the construction of stash campers, which are normal pickup shells that feature concealed, air-tight compartments capable of carrying up to 900 pounds of weed, “depending on how discreet you want to be.”

“Sixty or so of these have been built so far using my basic design,” he points out. “I sell ’em for about two thousand apiece.”

He shows me a concealed box in the well of one of the campers, all but indetectable. “You seal all these corners with your liquid plastic and put your piano hinges here, see? Shit, I’m a real master carpenter!”

The campers help him pay the rent, but Ferguson’s real business is still dealing. He’s not in the same league as Scott and Wesley—he estimates he pulls in about $25,000 a year—but he seems comfortable enough, putting together small deals when he can but mostly acting as a mule for larger ones. He is a long-distance driver of some distinction, maybe of genius. Time and again he has driven from the East to the West coast, popped another black molly, and turned around. But he’s showing signs of wear: his driver’-s foot is developing arthritis and a recent bust for which he is on five years probation has proven a significant nuisance in his career.

“I got turned in by a contact I shouldn’t have been dealing with in the first place. That’s the way it always happens. You get fingered by somebody who’s either a junkie or who won’t assume responsibility for his own screw-ups and weasels out.

“I’ll tell you, man, a lot of people get killed over this shit that are not reported. A lot of your heroin OD’s are not accidental. All the pigs do is find out they OD’d on junk and that’s it. End of investigation. Course there’s other ways. Traffic accidents—they’re a lot harder to stage, though. Then just general mysterious disappearances. People get so entrenched in the money they’re making they have to do something to support their lifestyle.

“Very little of that goes on around here, though. Very few people carry guns. This is a really mellow place.”

Ferguson also does a little cocaine fronting, a business whose profit margin is phenomenally higher than that of marijuana, since a gram of coke is in the same price range as a pound of weed and is much, much easier to hide. But there are pitfalls: big money tends to attract people not outstanding for their mellowness, and cocaine, white and powdery like heroin, ingested in such a depraved manner (through the nostrils, like a decongestant), has replaced marijuana as the new drug scapegoat; the laws, reflecting this conception, are very harsh.

Besides all this, a coke dealer’s own worst enemy is his product. Very few traffickers can keep their noses out of it, it is such a serene, easy-going high, sort of like watching television. Cocaine is also prestigious, given out by the gram at Christmas to clients in the same way businesses give out cartons of grapefruit or bottles of Scotch.

But although cocaine is still dealt in this part of the world, along with heroin, amphetamines, Quaaludes, and even a few psychedelic relics like LSD and psilocybin, marijuana is the drug of choice, the one that Ferguson estimates supports 2500 people in this county alone. A “mellow” dealer deals marijuana and maybe a little coke, but further down the drug spectrum the distinctions between conceivably benevolent and outright deadly drugs begin to blur and if his ethics are as laid-back as his lifestyle the dealer may find he has made some serious amendments to his outlaw code.

“Okay,” Ferguson says, beginning a lecture. “Here’s Mexico.” He is drawing a geography of the dope trade on a piece of rotting cardboard one of his dogs has dragged in from the yard. “All good pot is grown, unfortunately, south and east of Mexico City. In the mountains there you can buy it from these farmers for a hundred to five hundred pesos a kilo. In Mexico City, after it’s gone through this checkpoint here, the price is five hundred to eight hundred a kilo. Now here in the desert you got checkpoints all over the place, so moving it from northern Mexico to South Texas doubles the price again. You can buy it anywhere you want on this ladder. The people who make the most money are the people who move it the furthest. That’s where Scott and Wesley’s airplane comes in handy.”

Ferguson delivers a hard kick to his table saw (it’s still under warranty) and we go into the house to watch the news. One of the dogs jumps up on the couch and nuzzles against me.

“Tell me a dope adventure story,” I ask.

“What kind do you want? Desert adventures, ocean adventures, airplane adventures?”

“Desert.”

“Well, let’s see. There was the time in Arizona when we were two hours late to meet the plane and came roarin’ up over the mesquite trees in our custom Toyota Land Cruiser and behold! there was eight jeeps gathered around the plane. Well, we just did a hundred and eighty real quick. We had about $850,000 in cash that might have served to implicate us, see? The pigs gave chase, of course. My asshole associate emptied a clip from his AR-16 at ’em. Didn’t hit anybody, thank God.

“We made it back to town after one of those classic desert chases, changed the license plates on the Land Cruiser and had it painted pink. God, I still can’t believe we got away.”

On a moonless, almost balmy night in February, a caravan made up of four of Ferguson’s stash campers is heading west along a prominent highway en route to a “touchdown” with the Aerocommander. Scott drives the lead truck, followed by Wesley and the two other partners who have helped them put this deal together.

“Yeah, I suppose this is really the only scary part left anymore,” Scott says, bumping his head against the deer rifle on the rack behind him as the camper turns off the highway onto a dirt road. “But we’ve built our business to the point where we trust everybody we deal with. Anything that could go wrong now would be pretty much out of our hands.”

The plane will be flying in 1000 pounds of weed bought in Oaxaca last week for $32,000. It will be sold on this side of the border for about $200 a pound, for a gross profit of $168,000. Deducting payment for the pilot, for the owner of the ranch, and for gas, Scott and his partner should clear about $35,000 each for this month’s run. That’s an impressive statistic, and useful in placing any potential risks into a philosophical perspective, but I’m not convinced that this life is not more trouble than it’s worth.

It requires, certainly, a different constitution than the one I find myself with tonight. Scott and I are on different levels: something about us, something as basic as our metabolisms, does not mesh. The money he makes is a fiction to me, and I can see it is not all that real to him either—it’s not why he’s out on this road tonight in extreme violation of the law. The money is nothing, simply the lubricant of a vast obsession he shares with thousands, maybe millions of others: to live the life of an outlaw, to be alert to tangible dangers and the musk of his own fear.

But it’s a dangerous dream that may have run its course. Already, in certain attitudes, Scott has the look of a foundling. What will he do when marijuana is finally legalized and he must suffer withdrawal symptoms from his own high blood?

At about 10 p.m. the caravan passes across a cattle guard and pulls up to a small house that sits on the edge of a long, crudely graded runway.

Another West Texan named Jim Bob comes out of the house to shake hands. His long, thin hair is tied in a ponytail and he wears a Mexican vest over his black T-shirt. His father, a tall man in a print shirt and the bottom half of a leisure suit, steps out onto the porch with a Coors in his hand.

“How y’all boys tonight? Looks like a good night to do some business.”

The flight isn’t due for another half hour, so everyone goes indoors and stands around watching Johnny Carson and snorting cocaine through a twenty-dollar bill.

“How’s the new airplane?” Jim Bob asks Wesley.

“Beautiful,” Wesley says. “I’m going down on the next run just so I can ride on it. Goddamn Aerocommander, man.”

Soon Scott announces that it’s time to get ready. Jim Bob’s father takes a walkie-talkie and goes down to the road to watch for cars. Scott keys the microphone of the shortwave radio and the others set out a field of portable landing lights.

Ten minutes pass before the plane’s lights are visible very low on the horizon, much too low to be any other plane. There is an element of magic in it, the way this great machine has been called forth from the black depths of the sky. Soon we can see the Aerocommander itself, high-winged, pot-bellied, a swan-diver. As it lands and taxis toward Scott’s spotlight, the others run behind it and pick up the landing lights.

Once the plane has come to a stop the pilot steps out to stretch his legs and check the engine. He is Mexican, about 50, with a gun on his hip and an ebullient camaraderie that is surely motivated partly by nervousness. He shares a joint with Jim Bob while the other four load several dozen Mexican sugar sacks filled with pressed commercial weed into the campers.

“Goddamn, look at that,” the pilot says, pulling a branch off the landing gear. “I almost didn’t get off that time.”

After about twenty brisk, friendly minutes the plane has sunk back into the sky. The principals left on the ground take time for another joint before heading back.

“Smooth as glass,” Wesley says.

“I once had me this Gemini sweat-hog—God, she was good-lookin’!”

Ferguson has spread himself into an odalisque posture on the edge of Scott’s pool table and is sighting along the length of his cue stick as he speaks. When he finally makes his move he manages to sink both the cue ball and the eight ball without touching the striped six he was aiming for.

“Duel of the Titans!” he proclaims as I miraculously goose a three ball into the corner pocket. He then tells me a very long and involved story about how he and the Gemini sweat-hog were detained for two days at Kennedy airport because he had a “bad security profile.”

“You know what they meant by ‘profile’ don’t you? They meant my goddamn face! I just thank the patron saint of dope dealers I was clean for one of the few times in my life.”

After Ferguson has sunk the eight ball twice more I wander out into the living room and wait for Arnette to finish making peanut butter sandwiches for her kids. I want to talk to her about being a dealer’s wife. It’s a good opportunity: Scott has gone to rendezvous with the Aerocommander, which Wesley is riding in from Mexico with this month’s load.

Arnette has given the kids their sandwiches and the Mickey Mouse Club has gotten underway. We can hear Ferguson scratching his pool shots in the game room, a Mouseketeer doing a tap dance, and the grandfather clock striking the wrong hour with sonorous indifference.

Linda, a friend of Arnette’s who has been visiting all afternoon without saying anything, becomes intrigued with the sound from the TV and walks into the next room.

“I used to tap dance,” she says to herself.

Arnette picks up the shoe box lid and begins to roil a joint.

“The worst thing about being involved with a dope dealer is that they’re around other men all the time. And when they’re around other men all they talk about is dope. It’s all very boring.

“But I don’t have a right to talk. I mean I have a Lincoln Continental out there with an opera window and a little engraved tag with my name on the glove compartment. I’m just as much a part of this scene as Scott is.”

While we’re talking the phone rings. Arnette says hello and then for a long time nothing else. The silence is ominous enough to draw Ferguson in from the game room and Linda away from the TV.

“Oh God,” Arnette whispers into the phone. She takes a magnet off of the refrigerator and throws it back as hard as she can. Then she hangs up.

“Wesley is dead, man!” she says to Ferguson.

“Oh, Christ. What happened?”

“They don’t know. They know the plane crashed, that’s all.”

The details come in after a few more phone calls. The plane stalled on take off—some complicated aerodynamic failing nobody wants to go into—and nose-dived into the ground and burned. What was left of Wesley was found under a half-ton of smoldering marijuana.

“Well,” Ferguson says, after the shock has had a chance to settle in, “if he’d had his choice of the way he wanted to die, you know this is what he would’ve picked.”

“Oh shut up,” says Arnette.

The grandfather clock strikes again. The sound from the TV is suddenly loud and intrusive.

Mickey Mouse…

Mickey Mouse…

Forever let us hold our banner high…

“Ferguson’s right, though,” Linda tells Arnette gently. “That’s the way he would have wanted it.”

“I know,” Arnette says, “but please shut up.”